Challenges to Character Understanding

I recently read this post on Hacking Chinese: 5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure and it really struck a chord with me. It reminds me a little of my own “5 Stages To Learning Chinese,” but it highlights some really great issues related to character learning which I’d like to dig into.

I’ll first do a quick summary of the author Olle’s 5 stages, but in my own words:

- Chineseasy Mode: Fully arbitrary character-image associations

- Lazy Heisig Mode: Systematic arbitrary character-image associations

- Diligent Heisig Mode: Systematic character-image associations, with substitutions

- OCD Heisig Mode: Systematic complete character-image associations

- Scholar Mode: Straight-up character origin research

Apologies to Olle, in that I may be misrepresenting his 5 stages a little bit in order to make a few points, but I believe that our groupings are mostly similar, and in any case, I am piggybacking on his article.

Chineasy Mode

This is not a compliment. I’m not a fan of Shao Lan’s Chineasy, at least not for any serious student of Chinese. Chineasy is fine as a fun “Chinese Characters Lite” if you have no intention of becoming literate in Chinese. (See also Dr. Victor Mair’s thoughts on it.)

The problem with it is that it’s not a system. It’s just Chinese character dress-up. You can’t memorize thousands of Chinese characters without a system. It’s how the Chinese themselves do it, and it’s how learners need to do it.

The question, then, becomes: how complicated of a system does this need to be?

Lazy Heisig Mode

I’ve written a little bit before about James Heisig and his books Remembering the Kanji (for Chinese characters in Japanese) and Remembering the Hanzi (for Chinese characters in Chinese).

Heisig’s work was an absolute breakthrough in the 1980’s. It was a breath of fresh air at a time when no one seemed to understand that practical language learning and scholarly language study of Asian languages did not have to be the same thing.

Heisig had the gall to “blasphemously” suggest that some systematically recurring character components could be assigned arbitrary meanings that the learner made up himself in order to concoct little mnemonic stories help him remember the correct meanings of the full characters.

If the “arbitrary” part is applied in moderation, this is definitely an improvement over the previous level, becomes you’re bringing a system into it. You’re recognizing that many character components are clear and easy to remember, plus they repeat a lot across different characters, and there’s a good reason for it. For the ones that aren’t clear or easy to be remember, you have a plan B. It’s a pragmatic system.

The problem here is that not every component has an obvious meaning, and if you start assigning many of your own un-scholarly meanings when you only know 50 characters, you’re not going to fully realize until you get to 500 characters that you really shouldn’t have chosen that meaning for that particular character component. But to change it now means changing a bunch of stories you had memorized. Yeah… it can be messy.

Diligent Heisig Mode

So if you were “lazy” before because you didn’t care what most components actually mean (historically), you’re “diligent” now in that you at least try to match the character components you are learning systematically to some kind of historical meaning.

You’re also actually paying attention to the difference between semantic (meaning) components and phonetic (sound) components. The extra time and effort spent here will really pay off when you make it to the advanced levels of your Chinese studies.

Keep in mind, however, that sometimes the “historically accurate” character breakdowns are simply not helpful or not practical (see “Scholar-Only Examples” below). In cases like these, even the “diligent” student may need to make a call in favor of his own sanity. He may need to “make something up” from time to time, but he tries not to. (In any case, the characters he punts on are likely the same ones literate native speakers have no clue about either.)

OCD Heisig Mode

But what if having a rough idea of semantic and phonetic component roles is not enough? What if you have to know the role of every character component for every character?

Well, I’d say that you may be a bit OCD… Or maybe that’s just your personal interest.

In either case, you’re probably spending far more time on your system than you need to. (What’s more important: your system, or reading Chinese?)

I won’t say too much about this.

Scholar Mode

Some learners really want to know the ins and outs of every character. And that’s cool. Clearly they have an interest that goes beyond the average learner’s.

But is this how far a learner needs to go? No. Recommending other learners go this route reminds me of a conversation I had with my 9th grade algebra teacher:

Me: Can we use a sheet of formulas for the test?

Teacher: No.

Me: *crestfallen* So we have to memorize them all.

Teacher: Well, I didn’t say that…

Me: *hope in my eyes* What do you mean?

Teacher: Well, if you understand the principles behind the formulas, you don’t need to memorize them when you can simply derive them yourself whenever you forget them…

Me: *hopes shattered*

These two people are not living in the same world.

Assessing the 5

Like Olle, I’d put myself in group 3, and it’s what I recommend that most clients do. As an elementary learner I was once in “Lazy Heisig Mode,” but I eventually realized my “system” was a bit of a mess, and I did the extra work to get to “Diligent Heisig Mode.” It’s a good place to be.

I’d say the 5 levels apply to most people like this:

- Chineasy Mode: Tourists only! You’re not a serious learner, and that’s OK.

- Lazy Heisig Mode: You’re not fully committed, and that’s OK too. If you decide to “go all the way” with Chinese, you can still upgrade later.

- Diligent Heisig Mode: You’re committed, and you don’t want to waste time forgetting and relearning. You’re building a strong foundation for the long road ahead.

- OCD Heisig Mode: I’m not sure you really exist? But anyway, if you do… you do you.

- Scholar Mode: The world needs scholars! Thank you for your hard work. (Just remember that not everyone aspires to be at your level.)

Scholar-Only Examples

You may not understand why it’s difficult and messy to learn the correct origins of all the characters you learn. I felt the same way once. I was all, “hey, I like language. I can handle it.”

OK, fair enough. I have some examples for you. No, you will not see the characters 山 or 月 or 好 or 明 or even 上 and 下. Those are the ones used to prove the opposing argument. Let’s look at a very simple beginner-level sentence.

你是我的朋友。 (Nǐ shì wǒ de péngyou.)

This is a first-semester Chinese sentence which means “You are my friend.” Easy vocabulary, easy grammar. Now let’s look at the characters.

If you’re a serious student of Chinese, you probably know about the Outliers Chinese Dictionary for Pleco. Here are the entries for those characters:

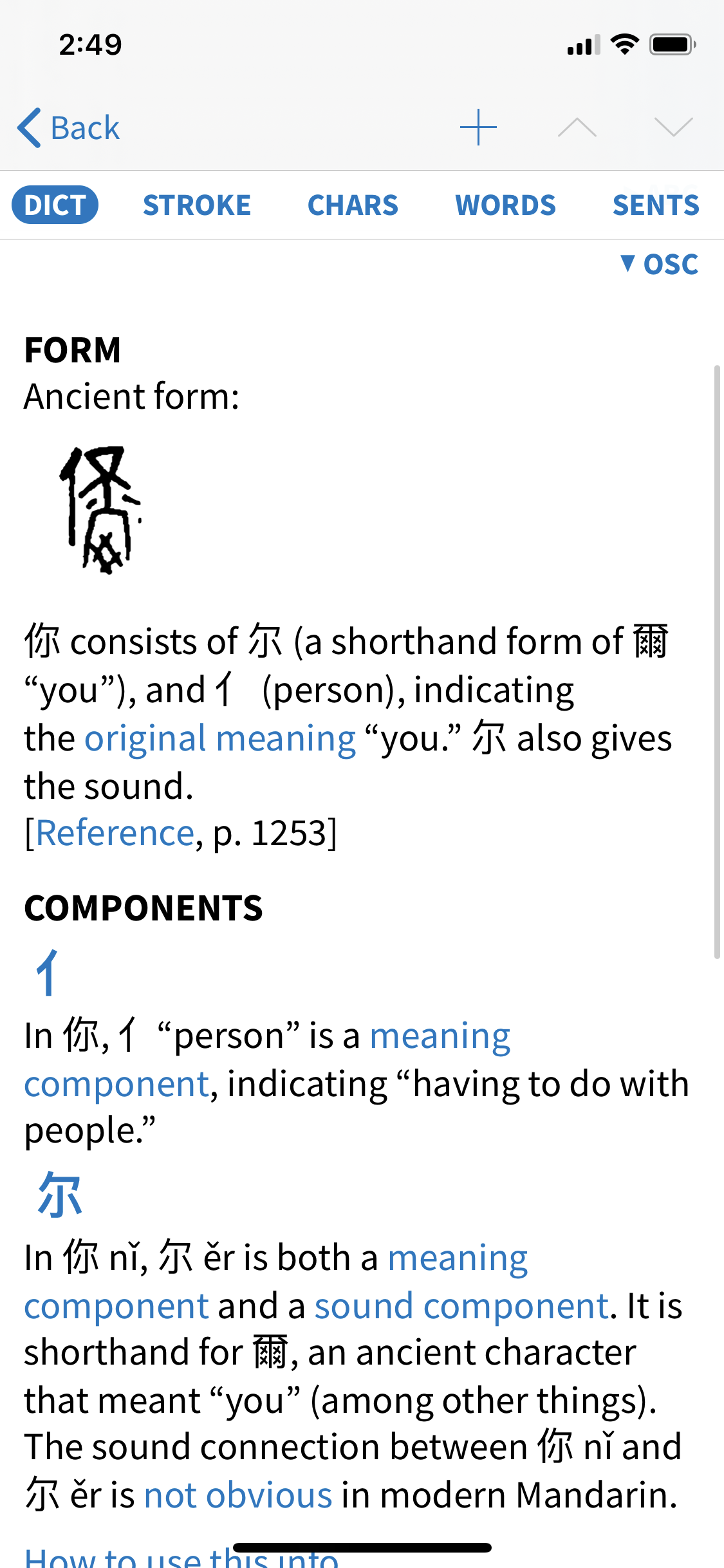

你 (nǐ):

是 (shì):

我 (wǒ):

的 (de):

Not in my Outliers Dictionary. This explanation is from Wenlin:

In ancient times 的 meant ‘white’. Therefore 白 bái ‘white’ is a component in 的 (white: bright: clear: precise: bull’s-eye). 勺 sháo (‘spoon’) is phonetic: ancient 勺 *tsiak (modern sháo) sounded like ancient 的 *tiek (modern dì).

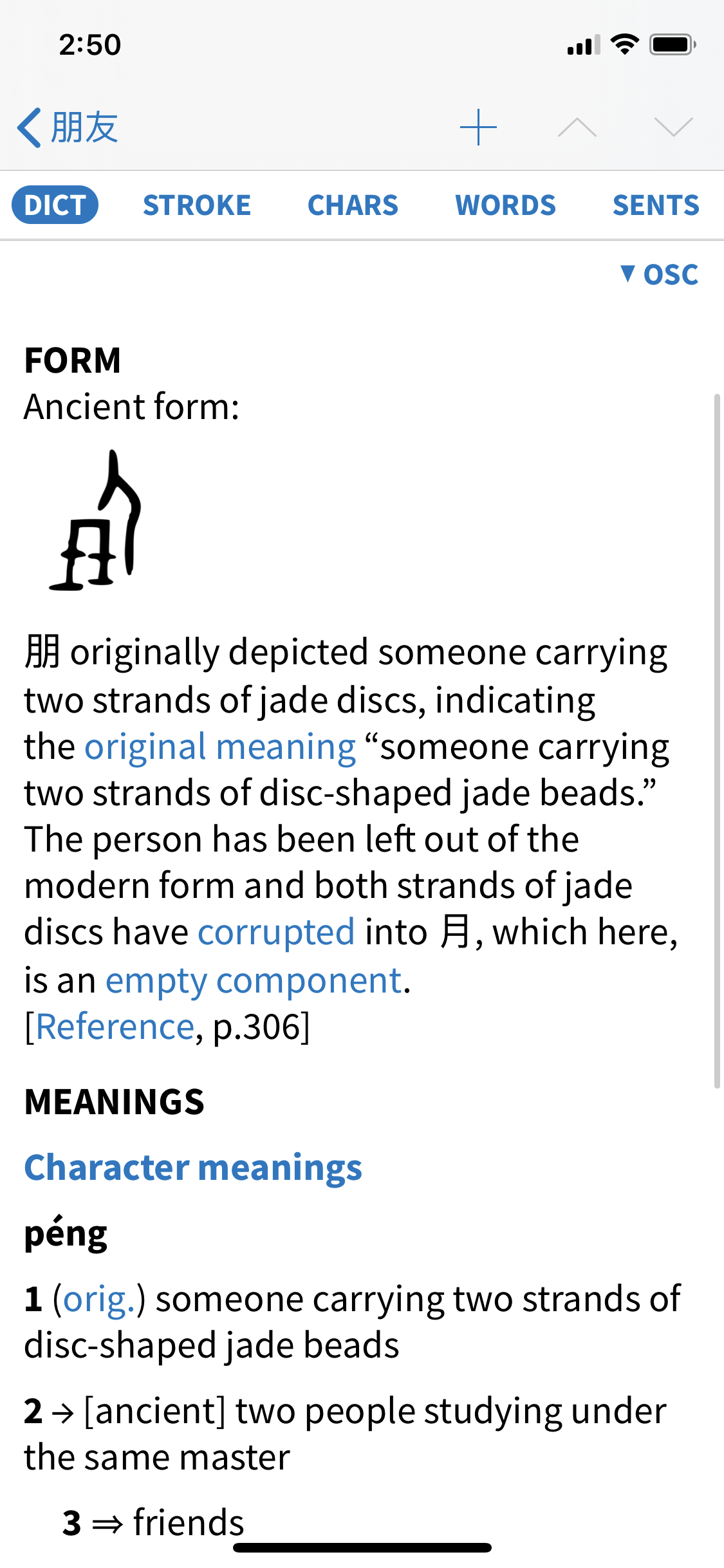

朋 (péng):

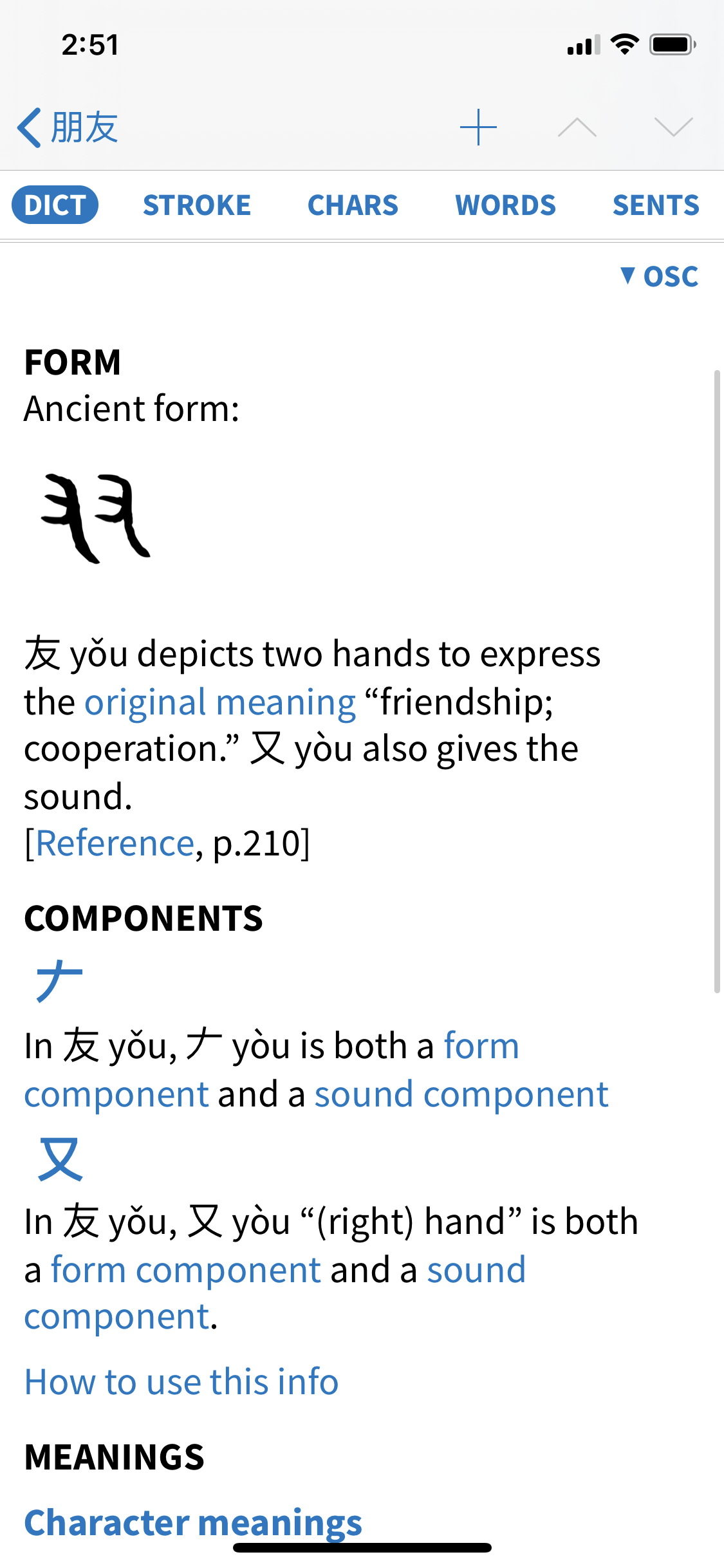

友 (you):

Holy crap. Don’t try to tell me that’s not a nightmare. It might be OK, if these were some cherry-picked exceptions, but they’re not, really. There are quite a few more common characters like this, although most characters are easier to make sense of when you break them down.

Try looking up the characters in this simple sentence if you want more trouble: 你不要说话! (Nǐ bùyào shuōhuà!)

Conclusions

The unfortunate truth is that many super-common characters have historical origins that are elusive to beginners, to put it nicely.

This is not the end of the world, though! If you’re in “Diligent Heisig Mode,” this is how you approach the “你是我的朋友” sentence above:

- 你: OK, the “person” radical is meaningful. That’s something! I’ll just have to deal with the right side somehow, since the character origin is useless to me.

- 是: All right, we have a “sun” (which I know!) and another component. This is a challenge, but it’s such a super-common word, that I can accept brute-forcing it into my memory somehow.

- 我: Yikes, a similar situation to 是, but with a much crazier form. Fortunately, there are not many of these.

- 的: Two clear components, and this is the #1 most common character in the whole language. So yeah… my memory can make an allowance for this one.

- 朋: OK, now we’re getting somewhere. A doubled-up component meaning “friend.” I can work with that.

- 友: Recognizable components. OK.

It gets easier, but there are a few speed bumps in the beginning. It’s for this reason that it can be very useful to not force yourself down that etymology rabbit hole for every new character you learn.

Most characters are composed of a sound component and a meaning component (they are called phono-semantic compounds), but the examples above are not so helpful in that way (even if some of them technically have a sound component). In any case, in order to “break into” the system and get it working for you, you have to do the work to learn the character component parts. Then the magic can start.

In conclusion: learn your character components (but not necessarily their full origins), and stay diligent. Your future Chinese literate self will thank you.

P.S. All my clients at AllSet Learning are strongly encouraged to become literate in Chinese using an approach similar to what I’ve discussed above. Feel free to get in touch.

P.P.S. I also discussed the Heisig method with my co-host Jared in our podcast, You Can Learn Chinese.