Japanese Pronunciation Challenges (totally different from Mandarin Chinese)

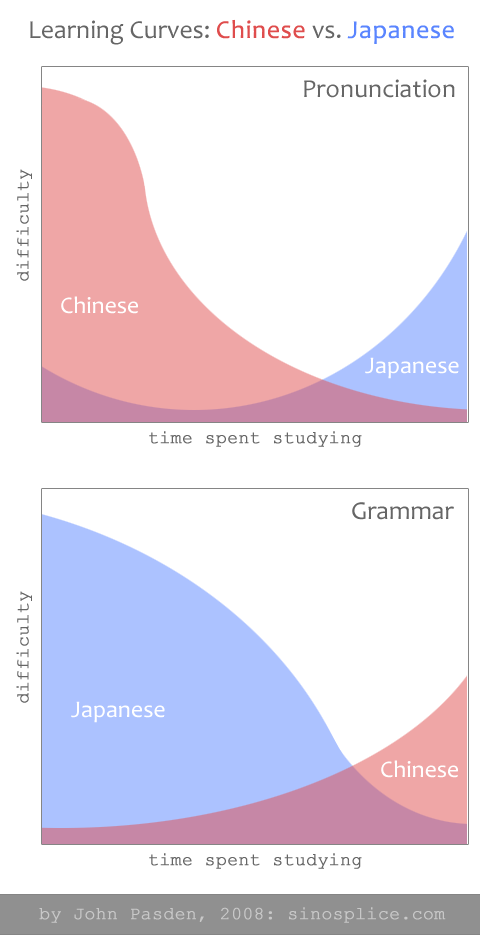

A while back I wrote about how learning Chinese compares to learning Japanese, difficulty-wise. It’s generated a lot of interest, but one point which many readers may not have fully understood was why the Japanese “pronunciation difficulty” line rises towards the end. Refer to the graph here:

So… What makes it more difficult when you study long enough? This is what I originally wrote:

Japanese pronunciation is quite easy at first. Some people have problems with the “tsu” sound, or difficulty pronouncing vowels in succession, as in “mae.” Honestly, though, Japanese pronunciation poses little challenge to the English speaker. The absolute beginner can memorize a few sentences, try to use them 20 minutes later, and be understood. The real difficulty with Japanese is in trying to sound like a native speaker. Getting pitch accent and sentence intonation to a native-like level is no easy task (and I have not done it yet!).

Recently I discovered YouTuber Dogen. He’s got a bunch of really great videos on advanced Japanese pronunciation, and this once does a great job of summing up and illustrating the 4 main types of Japanese pitch accent:

Got it?

I don’t know about you, but I never studied Japanese pitch accent in depth as a student. Not as a beginner, and not as an intermediate to advanced student. I remember I learned what it was, but it was never given a lot of emphasis. It really does seem to be something you typically tackle once you’ve confirmed that you’re a super serious learner, and “just making myself understood” isn’t enough anymore.

This contrasts with Chinese, where the 4 tones are thrown in your face from the beginning (there is no escape), followed closely by the tone change rules.

Interestingly, when Chinese learners in China study Japanese in school, they do learn pitch accent from the get-go, and the result is much more native-like pronunciation from a much earlier stage. I’ve witnessed this, and it’s impressive. Freeing up learners from the burden of kanji (Chinese characters in Japanese) means that time and effort can be placed elsewhere. (Similarly, Chinese learners tend to be a bit weak on the non-character syllabaries of Japanese: hiragana and katakana, over-relying on their character recognition advantage to get them through reading.)

LOL, by “a while back,” I apparently mean 12 YEARS AGO. I wrote that other article 12 years ago.

Kind of mind-blowing.

As someone that learned toneless Chinese, then spent years undoing the damage, I’d say that pitch accent isn’t for the advanced learner, but something everyone should learn. Learning the basic words and phrases (read: the ones you’re going use over and over again) without paying attention to pitch accent is a recipe for building up bad habits with the most common words. Dogen says that his pitch accent is good because he focused on pronunciation early on (that’s the simple version of his story).

I’m researching out all the rules and learning only words that I know how to say the pitch accent correctly. Of course, I know a lot of people wouldn’t want to do that, but at the very least, you should learn how to recognize it and know to look for it and spend a lot of time learning words/phrases via listening to audio. Once I get the rules figured out, I’m going to try and figure out a way to unify them to make it easier to learn. I’m willing to research out all these rules, btw, because of a deep desire NOT to repeat the pain and suffering I went through undoing years of speaking Chinese incorrectly.

My take on Chinese vs. Japanese pronunciation:

Japanese is waaaaay harder. There are way more accent types than there are Chinese tones and the interaction of pitch accents between words is waaaay more complex than tone sandhi in Mandarin. This is exacerbated by the fact that at the very least, the learner of Mandarin is aware that tones exist, while in Japanese, there seems to be a national conspiracy to cover up the fact that pitch accent exists (just joking. The Japanese themselves are generally unaware of pitch accent — Dogen made a really funny video about this). Most textbooks ignore or give it a one or two line explanation, giving the impression that there is a small set of words (like “bridge”, “edge” and “chopsticks”) that are affected by it, when it’s actually 99.99% of Japanese words that are. The ones that do explain it don’t give enough explanation and most of them don’t acknowledge that pitch accent is mora-timed, but a syllable level phenomena. A lot of people seem to think that “mora” is just what you call a “syllable” in Japanese, but it’s not. They both exist in Japanese and are both important when it comes to understanding pitch accent. Btw, I LOVE PITCH ACCENT! It’s one of the most interesting things I’ve researched other than Chinese characters.

The key difference is that bad pitch accent in Japanese doesn’t generally result in not being understood by Japanese people, whereas bad tones in Chinese mean that Chinese people literally cannot understand the words coming out of your mouth.

Not all learners have native-like proficiency as an end goal. If just “being understood” in casual conversation is the goal, then spending lots of time on Japanese pitch accent is overkill.

You can get really far in Chinese if *all* your tones are bad (voice of experience). If you’re tones are mostly correct, but you say one incorrectly, then you’ll be misunderstood. In fact, one of the ways I knew when my tones were becoming mostly correct is the reaction of listeners when I get one wrong. There is a visible reaction. I was talking to two people a year or two ago and said mǎlà (fossilized pronunciation error) when I meant málà. There’s not even a word in Mandarin pronounced mǎlà, but they both reacted like I had slapped them across the face and had no clue what I was talking about, even though the conversation centered around Sichuan food. If I had said the same sentence completely toneless, I bet they would have understood. The reason is, if all your tones are bad, they don’t pay attention to them and they are already in the mode of trying to figure out what your (weird) sounds mean. If your tones are mostly correct, then they do believe them and are therefore lead astray when you say something wrong.

Japanese is the same way. John was in a cab once. He said he wanted to go to “shibuyaku” (which he pronounced as unaccented — because “shibuya” is unaccented) and the cab driver had no clue what he was saying. As it turns out, when you add “ku” to a place name, the pitch drops on the syllable proceeding “ku”, which produces a drastically different impression, even to my ears. The reason the cab driver didn’t get it is because the rest of the sentence had correct pitch accent. If he just spoke the normal foreigner Japanese with all incorrect pitch accent, the guy probably would have gotten it. Japanese people from different regions do actually have difficulties sometimes and it’s largely due to different pitch accent patterns.

Despite the fact that most people aren’t aiming at native-like pronunciation, it’s always in the interest of the learner to speak clearly. Speaking clearly means getting the intonation somewhat correct (not saying native speaker correct, but at least in the ballpark). If you’re not even attempting to get the intonation correct, there’s a very high chance you’ll be using the intonation from your native language, which is going to sound bizarre to the listener and probably make them feel somewhat uncomfortable. The more comfortable the listener is, the better the communication will be and the more likely that person will want to continue talking to you and talk to you again in the future. On top of that, if I can train my ears to it — a guy that spoke a slaughtered version of Mandarin tones for many years — then so can anyone else. It’s really not that difficult if you spend time listening to and mimicking the language. For me personally, I want to know the road to native pronunciation. That way, I can help someone else get as far down that road as they want to travel.

Sure, it’s always good to strive for good pronunciation. We agree on that.

In my intro Japanese class we actually did discuss pitch accent from the get-go and I found it to be incredibly helpful. Our textbook, Japanese: The Spoken Language, while having many issues (the most glaring one being that it is relatively old and thus we had to learn useful words like “typewriter” but never learned how to say “cellphone”), was very detailed and words/sentences always included pitch accent markings, and the class was heavily oriented towards speaking and listening practice and relatively little time in the first semester was spent on reading/writing, and I think this was a really smart approach to the class.

What school was that, and when? I haven’t been a student for a while now, so maybe it’s changing…