Work-Chinese Balance

You hear a lot about the “work-life balance,” and what I want to discuss here is similar, but related to Chinese learning, of course. I’m drawing upon my own experience, as well as the experience of hundreds of clients at AllSet Learning, most of whom are learning Chinese for work-related reasons. Since most of my clients live and work in China, we’re talking about a natural second language learning situation (learning while immersed in the target language environment). Theoretically, at least, they could be using Chinese for their work, in some capacity.

Hence the term “work-Chinese balance.” If you live and work in China, how much do you use Chinese on the job? The answer could range from not using a word of Chinese ever (this is quite common for expat executives working for multinational corporations in Shanghai, for example) to using Chinese all day every day as part of the job.

It should come as no surprise that regularly using Chinese on the job results in much faster learning. Combine that with a practical, customized course of study focused on their work content, and progress can be extremely rapid. This is what I strive to help each of my clients achieve.

Can I have some Venn diagrams with that?

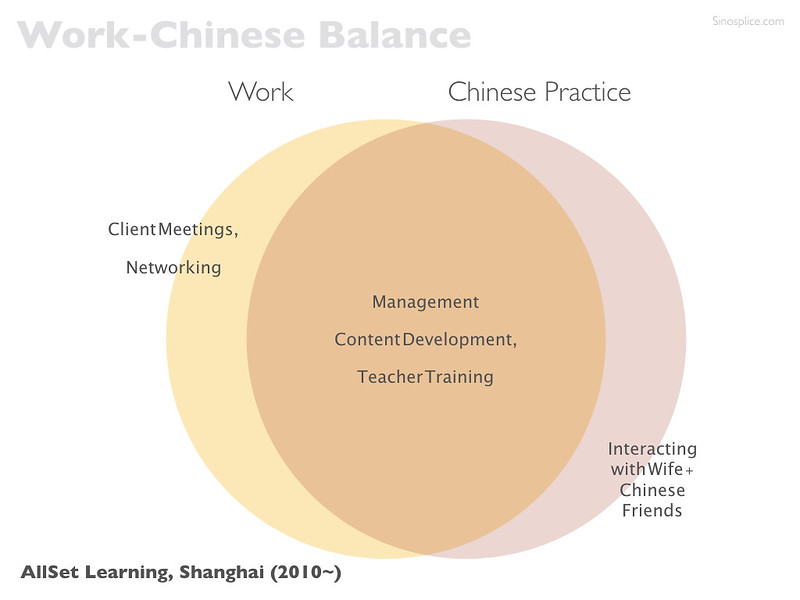

Time to Venn it up! Before getting into my own personal situation, let me just lay out some possible scenarios.

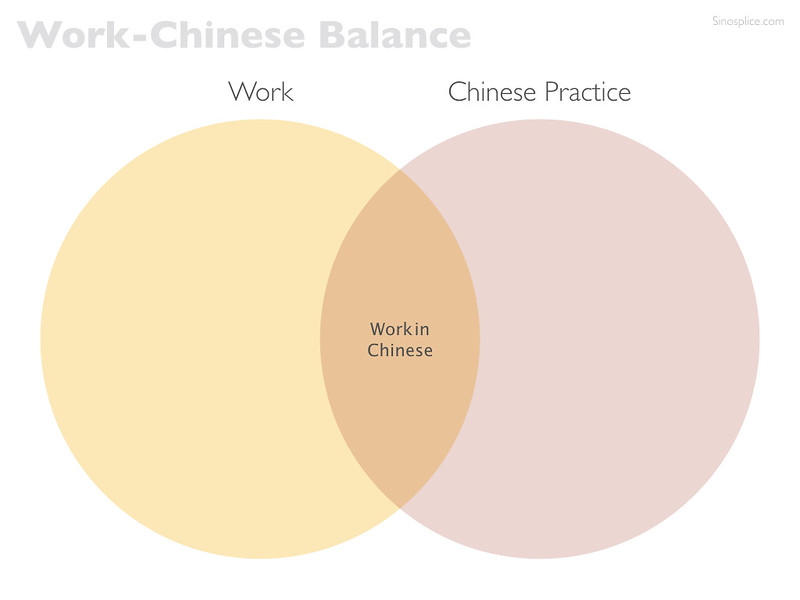

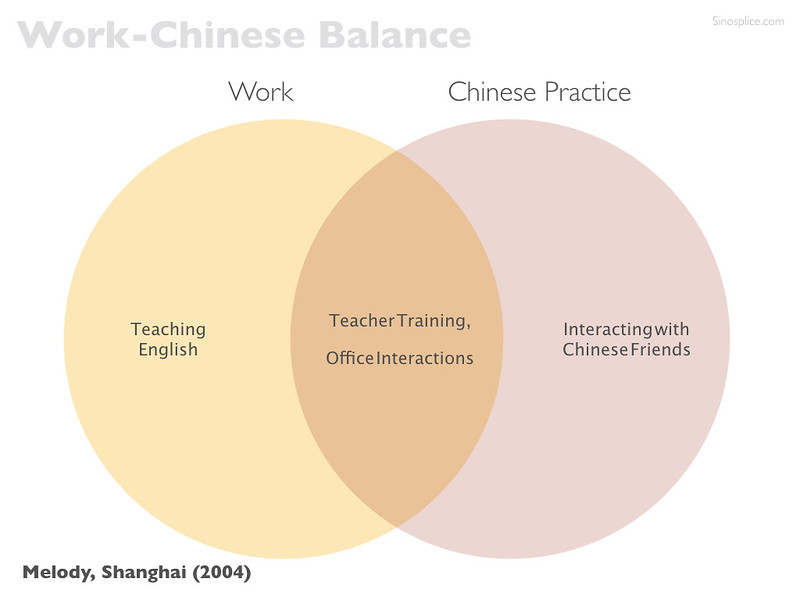

For many of my clients, they can use some Chinese on the job. The challenge is to use their Chinese more effectively, and to expand the scope of work which can be performed in Chinese. So it’s common to have this kind of situation, where some Chinese is used at work, but a lot of Chinese practice happens outside of the work place, and a lot of work is performed in English (or at least, not Chinese):

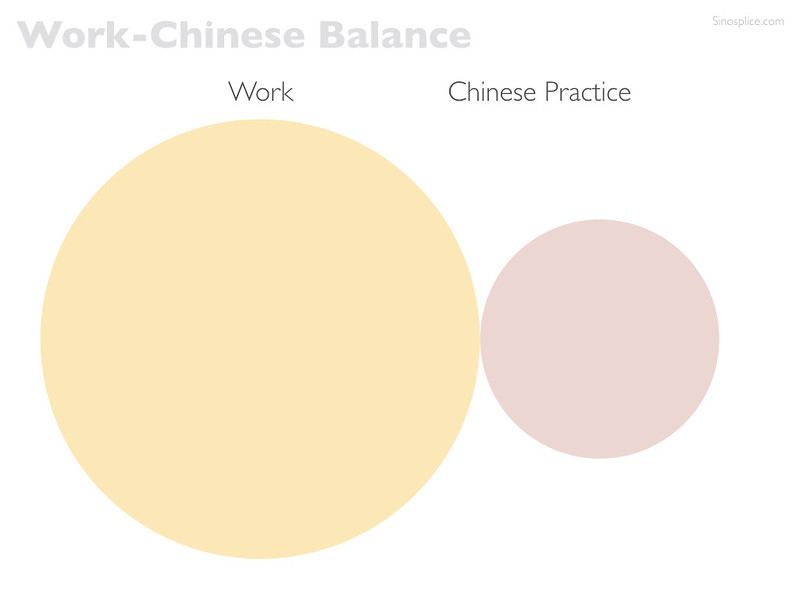

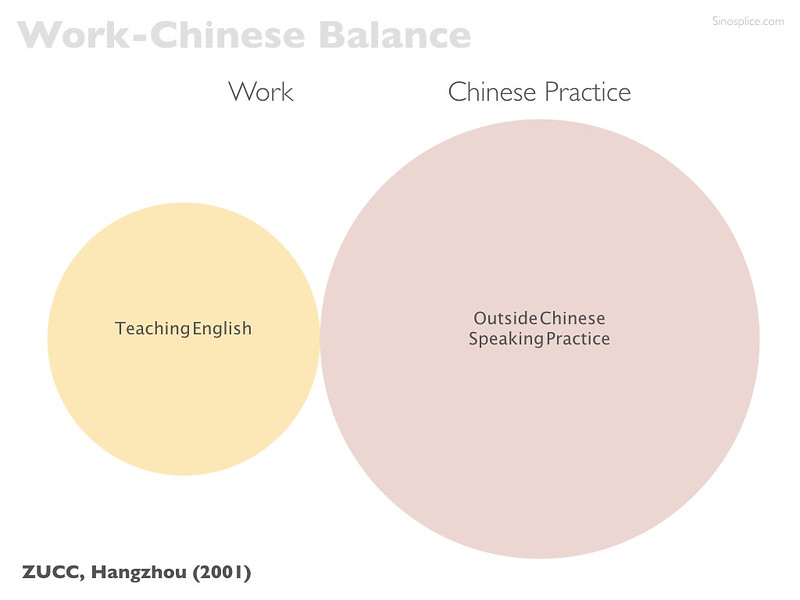

Worst case scenario is where the client doesn’t use Chinese for work at all, and maybe doesn’t practice much outside of work either (sizes are not meant to be exactly proportional here):

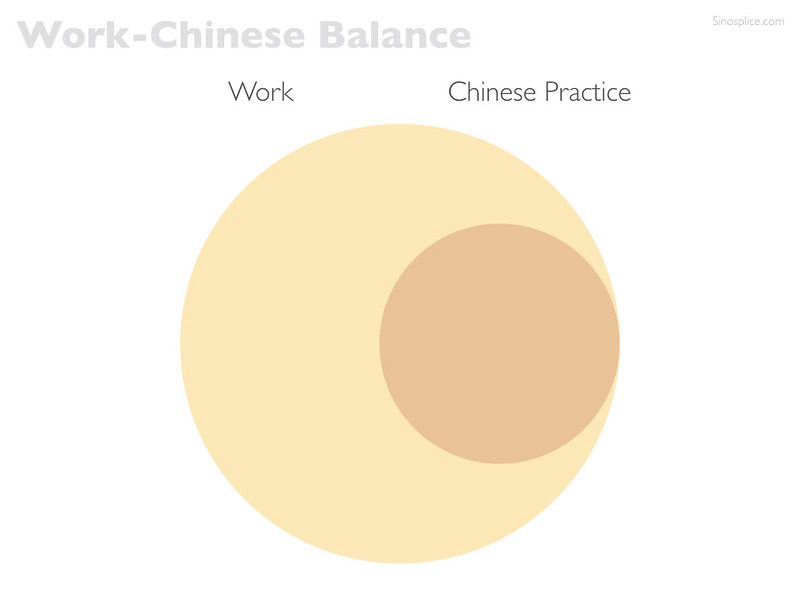

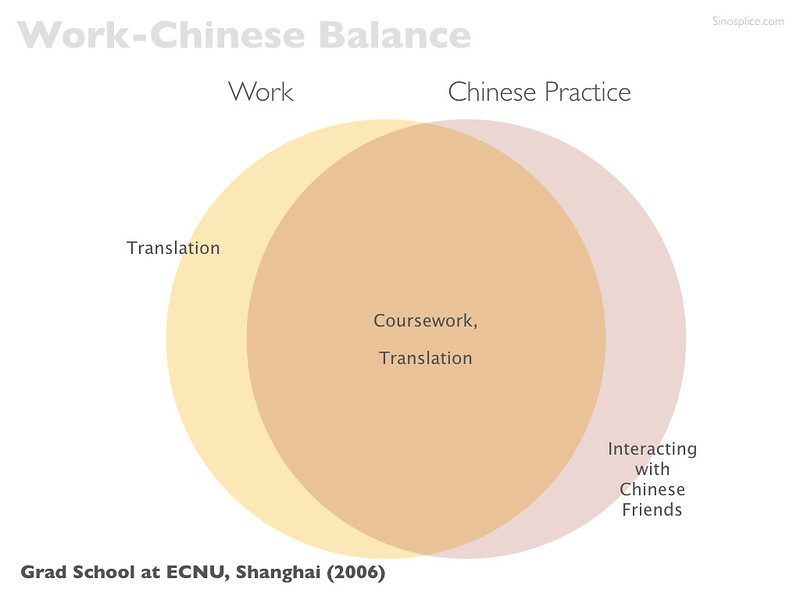

It’s also possible that a client could ONLY use Chinese at work, but only for part of the job:

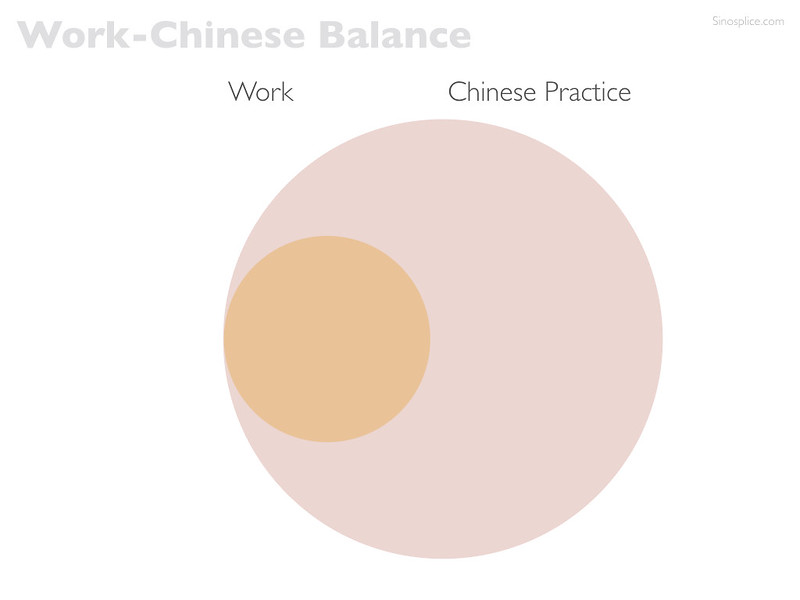

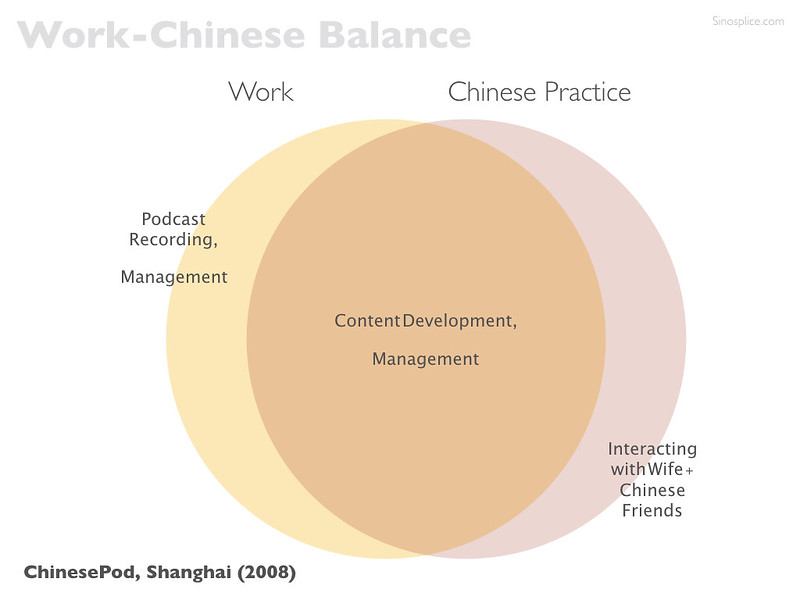

The opposite would be rarer: the client basically lives in Chinese, and that includes work. (Someone in a situation like this probably already has quite advanced Chinese. This situation would be more common for, say, an immigrant to the USA learning English than an expat in China learning Chinese.)

My Own Work-Chinese Evolution

I thought it would be interesting to chart my own work-Chinese evolution, since I’ve succeeded in gradually integrating Chinese into my career more and more over the years, and it helped me get my Chinese up to a high level. Let’s take a look…

When I first arrived in China I taught English in Hangzhou. I didn’t use any Chinese for my job, but I actually didn’t work a lot of hours every week, so I spent a ton of time studying and practicing Chinese in my free time.

After moving to Shanghai in 2004 I worked for a company called Melody. I was building on my English teaching experience, but starting to work Chinese into my job. This was an exciting time, and I made full use of the opportunities. My Chinese improved a lot, and I even had to speak Chinese on stage, in front of hundreds of teachers, for pronunciation training. A little pressure can be good!

I had to work hard to get into a Chinese grad school program in applied linguistics, and once I did it, I switched to a part-time job doing translation. This was good reading comprehension practice for me, but since I was producing written English and not speaking Chinese, I don’t consider it full “work immersion,” and for the purposes of this article I’m more concerned with speaking. You could also say that my grad school coursework was my full-time “job” at the time (I was on a student visa), and for that, I was fully immersed in Chinese. I got more listening and reading practice than anything, but it was still beneficial to my development, especially in sophisticating my vocabulary and upgrading my academic reading comprehension to adult-level.

Next came my 7+ year stint at ChinesePod. This was a lot of fun, and although I used a fair amount of English to communicate with upper management and other non-Chinese staff, I was also immersed in Chinese for most of my work. I got to geek out discussing linguistic issues on a regular basis. I was able to really flesh out my knowledge of Chinese, making it much more detailed. As a non-native speaker in the industry of teaching Chinese, the constant and long-term incrementing of my metalinguistic knowledge of Mandarin was super useful. I also got to have fun directing the creation of tons of lessons, which had its own learning benefits (frequently cultural).

Finally, I arrive at my current job at AllSet Learning. As a consultant, I’m in frequent contact with my clients, including face to face meetings, and most of that is in English. I also manage all the development of resources like the Chinese Grammar Wiki in English. But a ton of my work is spent working with Chinese teachers and other staff in Chinese. This also includes tasks like teacher training.

As the boss, I actually have control of what I do and what I use Chinese for. I made a choice early on for all office communications to be in Chinese, and I continue to benefit from this (you really never stop learning, as long as you keep paying attention). I even talk to our non-Chinese interns in Chinese! (OK, we do also have some English meetings outside the office.)

Final Thoughts

If you’re living and working in China, definitely give some thought to your own work-Chinese balance. It could make all the difference.

If you’re learning Chinese outside of China, all is not lost. This isn’t the only path, but it can be the most straightforward. (On the other hand, if you did something radical and got a job in China, then you could pursue something like this, and you wouldn’t be the first to be so “crazy.”)

For a related post on mixing “practice” (often work) and “study,” see also: How I Learned Chinese (part 4).

Recently I read a memoir by a South Sudanese who immigrated to Australia. He was a former boy soldier and he had horrific experiences. In coming to Australia, he threw himself into learning English. He spent a lot of time playing soccer, saying the game was the same all around the world. Eventually he gained an accounting qualification. The job was too challenging for him and he quit to work in a chicken factory. He said, “Although the smell was bad, I preferred it to working as an accountant.” Perhaps during this time his English foundation settled to the point where he could learn new topics through English. One can only wonder what Venn diagram this would fit into. Afterwards, he studied law, and he related in his memoir how difficult it was to comprehend the archaic language of the law.

FLUENCY – From my experience with about 3-4 friends, they became very fluent “native-like” in English (all had studied many years of English and were functional in English at a college level, but did not “sound” native) only after working in the U.S. for about 4+ years and using mostly English at work. One was a localizer, so she continued to use her native language quite a bit for the work. I mention this because it is in contrast to many others I have known that as adults immigrated to the U.S., but did not need to work predominantly in English, even though in the U.S. They hit a plateau and “frozen” state in their English development and never got to sounding native-like. So I don’t really believe in the concept that adults fossilize, although it’s really easier because of the environment.

I assume this would similarly apply to learning Chinese in China. For myself, as I don’t need to “work” in Chinese, although I’m in China, I have somewhat plateaued, and only make gains thru my conversations with others socially in Chinese. I think work provides motivation, a need, opportunity, repetition, exposure, etc., to make big gains. I do, however, feel that I continue to make gains, quite naturally by being immersed here…and paying attention.