The Case for Zhuyin

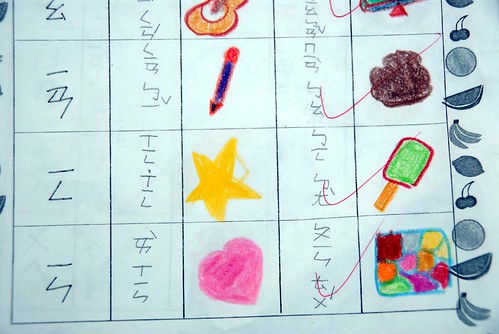

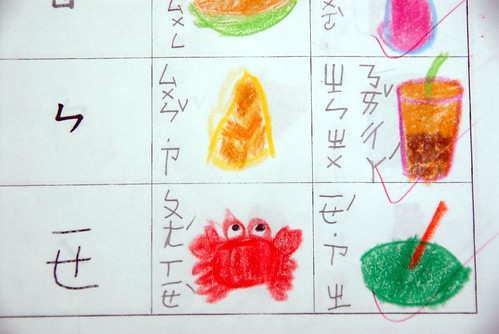

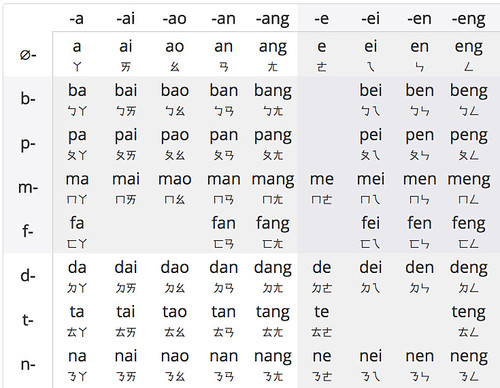

Zhuyin (also called “bopomofo”) is a system for writing Chinese phonetically, instead of using, say, pinyin. It’s pretty much exclusively used in Taiwan, but it’s quite popular among a minority of Chinese learners. The first time I saw it, I thought it looked like “bizarro kana,” as some of the symbols are similar to those used in Japanese. Some symbols also look like Chinese character components. It looks like this:

Mark of toshuo.com recently released a program called Zhuyin King (注音大王), which is still in its early stages, but aims to provide all the support one needs to fully master zhuyin.

When Mark made a post on Reddit, he was challenged with the question: why in the world would you learn zhuyin instead of pinyin? (A fair question.)

The best answer Mark gave was this one:

> When reading books annotated with pinyin, it’s very easy for the familiar Latin alphabet to draw your eye, even when you don’t need it. With zhuyin, westerners often tend to stay focused on the characters until they hit one they truly need help with… and then they look at the zhuyin beside it.

This is a big problem with a lot of Chinese learning materials: pinyin is featured too prominently, making it virtually impossible to ignore even if you really do want to focus on the characters before “cheating.” Zhuyin allegedly solves this problem.

Still, if you’re studying (or planning to study) Chinese in mainland China, no one uses anything but pinyin. So you have to wonder: who should be interested in zhuyin?

My answer:

1. Anyone planning to study or work in Taiwan (not mainland China) should learn zhuyin

2. Anyone that already knows some Chinese but plans to move to Taiwan for more than a month or two should learn zhuyin

It’s not that no one uses pinyin in Taiwan (more and more people do), or that you can’t get by without it (you certainly can); it’s that only if you learn zhuyin can you have the “no cheating” advantage listed above. (Mark estimates that the number of learners of Chinese is “about 15% for foreign students and most of them are either learning in [Taiwan] or 2nd generation [Chinese].”

If you’re just interested in browsing the zhuyin symbols, check out AllSet Learning’s pinyin chart. Click on “Show more Settings” and you can choose to display zhuyin for every pinyin syllable:

Related Links:

– Wikipedia: Zhuyin (Bopomofo)

– Chinese Pronunciation Wiki: Zhuyin

– Chinese Pronunciation Wiki: Pinyin chart (with zhuyin support)

– Hacking Chinese: Learning to pronounce Mandarin with Pinyin, Zhuyin and IPA: Part 2

– Zhuyin King (注音大王)

Thanks for the shout out, John.

I’ve found Zhuyin really helpful for people in terms of phonics. It was made with Mandarin phonics in mind, and the vowels ㄧ, ㄨ, ㄩ, ㄚ, ㄛ, ㄜ, ㄝ each map to one and only one sound.

With pinyin, a lot of beginners struggle with u sometimes being an ㄨ sound (e.g. bu, chu, lu) and other times being an ㄩ sound (e.g. ju, qu, xu, lü). Similarly e could be an ㄜ sound or an ㄝ sound.

It’s not impossible to learn Mandarin phonics well through pinyin, but there are challenges, especially for those who know the alphabet through a different language already. The ㄅ or b from pinyin is not the same as the b in English!

The primary use I hope Zhuyin King fulfills is helping people either new to the language or who have been learning through pinyin only with their phonics. If it gets people reading books books from Taiwan, though, that would be great! There’s an incredible selection, even of things aimed at kids and teens that has zhuyin annotations and censorship isn’t really a thing there.

Pinyin being obtrusive is definitely my experience (v basic learner) – not only attracting the eye away from the Hanzi but, as Mark says in his comment, conditioning how I think of the sounds; even perhaps how I process what I hear.

I’ll try out Zhuyin King.

Ivan

Zhuyin King is still in an alpha state. It is super discounted and you would get future updates for free, but if you just want to check out zhuyin and see what it is, I’d suggest this free site: http://www.mdnkids.com/BoPoMo/

Also, I made a converter long ago so you can see what how zhuyin was converted into pinyin 50 some years ago.

Thanks 🙂

I learned both at approximately the same time. They do an equally good job with Mandarin phonics. Pinyin was created by Chinese linguists to help spread putonghua after the CCP came to power, so it is entirely a native system. The one area I believe zhuyin has a clear advantage, though, lies is learning how to read characters. Zhuyin can be printed right alongside characters, so you can see at a glance how to pronounce the character. It also better maintains the flow of Chinese reading, particularly for traditional typeset (top to bottom, right to left). I hope we can download Mark’s app soon; it’s been years since I’ve tried to read zhuyin and I want to quiz myself!

While studying Chinese in Taiwan I made the deliberate decision to focus on pinyin and avoid Zhuyin. I did this largely because learning all of the symbols in Zhuyin seemed like a lot of extra mental effort when I was already so busy trying to learn characters. Learning the “quirks” of pinyin seemed easier.

I have never been swayed by the phonics argument. Pinyin is far from perfect, but it is consistent, which is all that really matters. Plus when you take into account accents (including the Taiwanese accent) all the carefully learned phonetic distinctions require re-mapping anyways. I saw several Taiwanese friends forget what the “correct” Zhuyin was, which sort of defeats the purpose.

So although I am kind of in the “why in the world would you learn zhuyin instead of pinyin?” camp, I do concede that Mark has a point about the pinyin being distracting when reading annotated characters. It just doesn’t blend with Chinese characters, and it is impossible to ignore.

That being said unless the situation in Taiwan has changed since I was there (very possible), 99% of annotated texts with bopomofo were directed at children (like the pictures in this blog post). This is not really that helpful for an adult. You get tired of reading about frogs and cats very fast!

I would have changed my mind if I could have found adult material with difficult characters annotated with Zhuyin, like they do for Japanese with furigana, but there really wasn’t much available.

If I am wrong about this and there is enough adult material annotated in Zhuyin that would be great for Chinese learners in Taiwan. It wasn’t available when I was there.

Zhuyin is actually used in some materials up through the high school level, so there’s a lot of content. I got a lot out of kids books. I read about famous stories from the 3 kingdoms era, European scientists such as Faraday, and a lot of stuff that was both interesting and well written. The bookstores in the underground metro malls and the big box stores like 愛買 were my go to places.

I wonder if maybe by consciously avoiding learning, you were blind to the annotations around you? I saw them on a pretty regular basis everywhere from menus to political campaigns to business cards. They’re also super heavily used in online chat (and a good number of my fb friends’ status updates). I know you can avoid learning them as a student in TW, depending on your text books, but it’s such a trivial task it seems like the return on the effort would make it an easy win for anyone actually living in Taiwan.

I’m kind of amazed at your story to be honest!

As for accents, yes Taiwan as a huge number of second language Mandarin speakers, as is common in Southern China. But encountering or even learning from someone with a strong Fujian accent doesn’t mean you have to remap all you learned! You’d need to redouble your efforts with ㄓ/ㄔ/ㄕ vs ㄗ/ㄘ/ㄙ. At least they’re completely separate symbols! You might also have to watch out for as well as ㄣ vs ㄥ and in extreme cases ㄌ vs ㄖ and ㄏ vs ㄈ. But there isn’t anywhere in China I’ve been to yet, where people use a b sound as in the b from English or where Mandarin speakers mix up ㄨ and ㄩ (the u from qu vs the u sound in chu).

In any case I’ve never yet found an alphabet that took anywhere near as long to learn as the sounds it represents. This even includes, Thai, which is about as baroque and complex of an alphabet as I’ve ever seen!

I am re-reading my comment and I did write “all the carefully learned phonetic distinctions require re-mapping anyways.”, which was a careless mistake on my part.

Of course not ALL of it requires re-mapping and you are absolutely right about the sounds that do change in Taiwan. Although I would point out that Mandarin native speakers (and not just second language Mandarin speakers) substitute ㄗ/ㄘ/ㄙ for ㄓ/ㄔ/ㄕ, and ㄣ/ㄢ for ㄥ/ㄤ. Many of my friends in Taiwan spoke this way and most did not speak Taiwanese or Hakka as their first language. It’s just a common and easily identifiable characteristic of Southern Chinese.

After I learnt the pronunciation I did learn enough zhuyin to read the occasional annotation in Taiwan, although I confess I’ve now forgotten most of it.

The only zhuyin my FB friends ever use are for “particles” and usually to be cutesy, such as ㄚ or ㄟ. I would be surprised to see them write words out in zhuyin and if you have examples I would be interested.

I agree wholeheartedly with the last paragraph you wrote. The alphabet is the easy part (whichever one you pick) the pronunciation is the tough part (that I can’t say I’ve mastered even after 10 years). My friends who learnt zhuyin first were told that this was a shortcut to better pronunciation and would bypass all the errors foreigners make in Chinese. If only that were true!

[…] https://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/2015/10/15/the-case-for-zhuyin […]

The “zhuyin is less likely to draw your eye” makes sense, but if you actually learn zhuyin really well, then I expect this advantage will become less pronounced.

It’s been my Chinese input method for over a decade now, and I haven’t had that problem yet. Then again, I haven’t been reading books or even sentences of Zhuyin text.

As a Mandarin learner living in Taiwan, Zhuyin is essential if you want to learn characters through reading. Books from pre-school all the way through middle school are annotated with Zhuyin. I’ve read abridged or annotated versions of 3 Kingdoms, Water Margin, Journey to the West, Tang poetry, Analects, etc all with Zhuyin ruby text. Bear in mind, almost anything with Zhuyin will use Traditional Chinese, standard in Taiwan.

In reality, you can learn Zhuyin in 3-5 days tops. There are flashcard apps out there for both iOS and Android that will teach you Zhuyin.

Tips for learning Zhuyin like a boss: If you’re using Pleco, select show ONLY Zhuyin. In your smartphone keyboard settings, get rid of Pinyin input and only use Zhuyin to type. Note, this last recommendation will have you typing like your grandma for at least a month, but with persistence is worth the effort.

The zhuyin debate is always a fun one, with merits all around. Started simplified Chinese in the US, then Taiwan, then Mainland. I didn’t see this mentioned, but the official language schools in Taiwan have switched to “hanyu pinyin” (often referred to as “roma pinyin” in Taiwan), as the default teaching tool, but zhuyin and Taiwan’s MPS pinyin is also represented (4 notations for every sentence in the textbooks).

My personal thoughts are:

Most foreigners seem to be sticking with hanyu, unless they are taiwan diehards

hanyu is faster to type than zhuyin, and there will usually be latin on a keyboard anywhere in the world, zhuyin not as likely (for any that disagree, i am happy to hold a typing test. I’ve done this many times with computer savvy taiwanese)

zhuyin usually requires typing the tone, so it’s probably a much better way to practice tone memorization compared to hanyu, which doesnt need it for typing

learning zhuyin when you’re tackling everything else knew in the language is tough (but i also agree with Mark’s comment it’s a small investment with big gains)

decide to either learn it, or just ignore it

I found that i learned to read 60-70% of zhuyin thru inverse deduction. that is reading the kids books, and looking at the zhuyin of characters i knew to figure out the sound of each zhuyin character

as I got better at zhuyin in the kids books, i did find it more distracting, similar to how hanyu pinyin can be (not nearly as bad, i admit)

pinyin is semi-useless for maps and street signs in taiwan.

it’s almost completely useless for trying to explain language elements to locals. personally, this was the main area i always wished my zhuyin was better, so clarify the phonetics of a character in question

now that i’m in mainland, i enjoy informing locals about the “other pinyin” which i have found people to be almost completely unaware of. It’s always interesting to see native speakers learning something new about their own language.

At the end of the day, knowing zhuyin will not hurt your chinese learning, and it might help it (possibly a lot). Or you might never need it…

Yussef do you have any citation to this effect? I checked with Shida and Taida (the two largest and prestigious public schools in Taiwan) recently and both are using several books that don’t even include Hanyu Pinyin. I believe the standard for the beginners is still PAVC which includes both, and they still have an optional phonics course for beginners that’s zhuyin-only.

From Shida’s page:

[…] books frequently have bopomofo in them. My tutor and I made an easy to read bopomofo chart that I think you will […]