Why Learning Chinese Is Hard

I can’t agree with anyone who says that learning Chinese isn’t hard, because it’s got to be one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Sure, it’s been extremely rewarding, but I personally found it quite hard. Hopefully you’re not someone who chooses to learn a language based solely on how difficult it is perceived to be. But as someone who has chosen to learn a language for the wrong reasons before, and who also once shied away from Chinese, daunted by those terrifying tones, I can tell you that it is definitely difficult enough to scare off the casual dabbler. But what exactly is difficult about learning Chinese?

First of all, let’s get one thing straight. When I say “difficult,” what do I mean? Here’s a definition from the Oxford Dictionary of English:

needing much effort or skill to accomplish, deal with, or understand

So when we talk about difficult, we shouldn’t confuse this with time-consuming. John Biesnecker recently wrote a great post explaining why the time-consuming nature of studying Chinese does not make it difficult, followed by extensive, patient clarifications in the comments.

But John also says:

…learning Chinese is a long, drawn out series of really easy things — learn a character, learn a word, listen to a song, talk to someone, watch a movie, write an email, 等等. Not a single one of them is hard. Not one.

While I agree with most of John’s premise, I can’t agree that nothing about learning Chinese is hard. I found learning Chinese very difficult in the beginning. Although difficulty is subjective, I think there’s an important part of the equation missing here. First, two examples from my own life.

Putting in Time vs. Acquiring a Skill

When I was in high school I played a video game called Final Fantasy II. It was an RPG for the Super NES which can be beaten with the characters in your party at around level 40. Nerdy kid that I was, I loved that game so much that I continued playing it long after I had beaten it, until all my characters were up to level 99. You might call that feat silly or sad, but it was essentially a very long (but somehow enjoyable??) slog to reach increasingly higher level-up points. It was a ridiculous time investment. But one thing it certainly wasn’t is difficult.

Another example from my awkward teen years. My cousin Kevin introduced me to juggling. He insisted that anyone could learn it in one day, if they just stuck to it. After trying a few times, this seemed hard to believe. Juggling just three balls for even 10 tosses was deceptively difficult. But for some reason I dug in and kept at it. After 30 minutes I could do those 10 tosses. After an hour, I was starting to look like I could juggle three balls.

Does it seem wrong to say learning to juggle is difficult? It honestly takes less than an hour if the learner keeps at it. I’ve tried to teach quite a few people to juggle, and the conversation usually goes like this:

Learner: Wow, you can juggle?

Me: Yeah. It’s not very hard. You can learn in 30 minutes if you try.

Learner: Really? Let me try.

[I demonstrate the basics and hand over the balls. The learner takes a few tries, quickly dropping the balls.]Learner: This is harder than it looks!

Me: Yeah, but if you keep at it for 30 minutes, you’ll be able to juggle.

[5 minutes pass.]Learner: This is too hard! See ya.

So why is juggling hard, even though 30 minutes is enough to get the basics down? It’s because it requires the mastery of a new skill, which, our brain reasons, “shouldn’t be too hard.” The logic of the task is quite simple. Throw ball. Catch ball. Repeat. The brain grasps the concept immediately. But the hands do not comply. The skill is too foreign.

In essence, it’s “hard” because it’s frustrating. Actual performance does not live up to one’s reasonable expectations for one’s performance, and this is a blow to one’s ego. It’s emotional, not rational. What’s worse, if this simple task cannot be accomplished as easily as estimated, how can you be sure you’re ever going to get the hang of it?

This is the crux of the difficulty of learning juggling, Chinese, and many other worthwhile skills: the sheer frustration of the endeavor, and the ever-present fear that one is attempting the impossible. It takes a lot of effort to acquire an entirely new skill. Many people simply get discouraged and quit. “It’s too hard.”

The Hard Part

When I say that learning Chinese is hard, I don’t mean everything about it is difficult. For me, the hard part about learning Chinese, without a doubt, has been mastering the tones. The worst part was arriving in China after a year and a half of formal Mandarin study to make the horrifying discovery that no one in China understood my Chinese. I’m not one to give up easily, however, and I eventually made it. In my experience, tones are the single most frustrating thing about learning Mandarin Chinese.

Why? Well, to begin with you can’t even distinguish the tones. It seems impossible. Then, once you start to be able to distinguish them, you can’t reproduce them on your own. It seems impossible. Then, once you can produce individual tones in isolation on your own, it all falls apart when you try to string tones together. It seems impossible. Then, once you can start to string tones together with some semblance of accuracy, adding in sentence intonation screws everything up. It seems impossible.

See a pattern? Mastering tones is a long, frustrating process. I think there comes a point in almost every learner’s experience (me included!) where they say something like this:

What’s wrong with these people? I said everything perfectly. I know all my tones were right. But they always act like they can’t understand me!

This is pure frustration. It happens to every learner.

Einstein once said that the definition of insanity is “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” Sometimes acquiring Mandarin’s tones seems perilously close to this definition!

The Good News

The good news is that although Chinese has a steep learning curve, the worst part, by far, is right at the beginning. You have no choice but to tackle the tones right off the bat, and they’re just hard. But once you get a handle on them, the worst is behind you. (This is, however, where John Biesnecker’s “time-consuming does not mean difficult” argument kicks in, and you still have a long road ahead with the characters and vocabulary acquisition.)

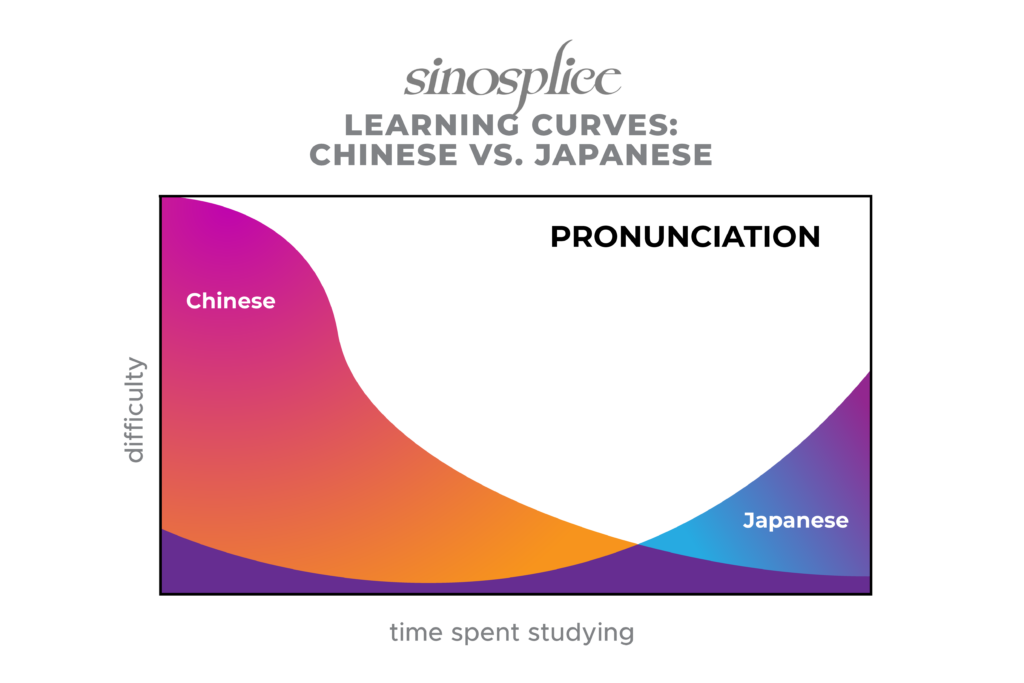

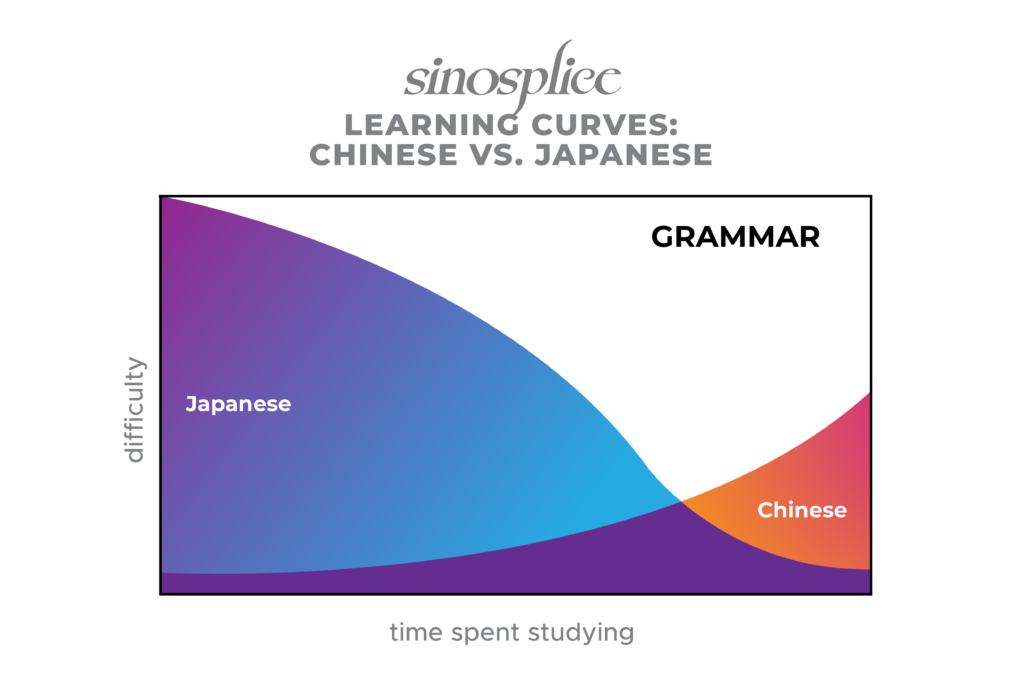

I essentially expressed this point a while back when I compared the difficulty of learning Chinese and Japanese:

Because the hardest part is right at the beginning, I think advanced learners can sometimes forget how difficult and frustrating it was. But it’s a key issue I face on an almost daily basis in my work at AllSet Learning. For beginners, the learning curve can be a bit brutal.

You’re not afraid of a challenge, are you?

Mastering tones may be difficult, and memorizing all those characters may be time-consuming, but learning Chinese is definitely worth it. Difficulty is a subjective thing, so there may be those with an uncanny knack for acquiring tones (or perhaps indefatigable, saintly patience) who honestly don’t find it difficult (or frustrating). I’m willing to bet that some learners simply have a penchant for blocking out distant painful memories, and there may even be a few out there with devious plans to trick you into falling in love with Chinese. It is, after all, one of the world’s most fascinating languages.

There have been a number of excellent articles already written on this topic. I’ve linked to some of them below. Please note that David Moser’s article is tongue-in-cheek. Brendan’s conclusion is spot on, and I think Ben Ross’s views are also very close to my own.

- Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard by David Moser

- …so, you want to learn Chinese? by Brendan O’Kane

- Journey Across the Great Hump of China: Debunking the Myth that Chinese is the World’s Most Difficult Language by Ben Ross

- How Hard Is Chinese to Learn, Really? by Albert Wolfe

- Learning Chinese: How Difficult is It? by Truett Black

- Learning Chinese isn’t hard by John Biesnecker

Relevant Sinosplice content:

- The Process of Learning Tones

- Mandarin Chinese Tone Pair Drills

- Chinese Pronunciation

- Tone-related blog posts

Great post. In recent months I’ve found my approach to Chinese changing a lot.

At first it was about being able to speak… then it became about speaking well enough to do your job, that took some time (about 500 phonecalls later, I had it down).

For me now, its about doing presentations in Mandarin, and doing them well. If you want to be regarded like a respectable CEO/salesman in Mandarin, you have to go way above and beyond the requirements of ordering food, chatting to girls at a bar, etc.

And in that ‘huge challenge’ I’ve found my love for learning Chinese again!

One of the hardest things about it, is that many of the Chinese you meet in day to day life aren’t really that ‘eloquent’ with Chinese at all. They throw words around, talk really fast, mumble something in a local dialect, point and yell at stuff, but aren’t exactly eloquent. That search for eloquence is incredibly difficult because it involves eons of Chinese history and culture. To be eloquent in Chinese is to memorize tons of expression and colloquialisms that you will most likely never come across in day to day life. One of the reasons it’s hard is that you can’t learn it by osmosis.

Thanks!

Yeah, I can definitely identify with the challenge being a motivating factor. I had to do class presentations in Chinese for the first time as a master’s student, and I found it incredibly difficult at first.

It doesnt sound the same as you learned it because they speak ‘slang’ chinese.

Excellent post! Thanks John, I enjoyed it a lot!

Thanks, man!

Very good post, John.

I wonder how much of the “frustration == hard” thing comes from inexperience with learning languages (or at least languages that are as radically different from Western languages as Chinese is)? I will certainly concede that the frustration of learning tones can feel hard, and it is the perception of difficulty that matters in the end. However, having started with Cantonese, whose pronunciation can be pretty maddening even for Mandarin speakers, I’m much more at ease than I probably was when I started with Mandarin because I know that it can be done.

Chinese still isn’t hard, though. 😛

I bet familiarity with a tonal language helps a lot, although some research claims this is not true. (I know that Americans who speak Cantonese can learn Mandarin very quickly, for example; I’ve seen this with my own eyes.)

I think that learning a truly foreign new skill is pretty much always frustrating (read: hard).

It’s time consuming. It’s frustrating. And it’s definitely not easy.

On the one hand, most people think learning Chinese is incredibly hard (and difficult). On the other hand, my gmail ads are always telling me that Chinese is easy: apparently I can learn it in 10, 30 or 90 days. The truth is probably in between.

I prefer to make it into a challenge: over 800 million people have been able to learn Mandarin Chinese, so it’s not impossible. And there’s no way I’m going to give up on something that so many people are able to do. (I wrote a post about this.)

I firmly believe that anyone can learn any language. Our brains want to learn a languages.

I like a challenge as well.

True, our brains want to learn language. But they often try to take the position that “one is enough.” 🙂

Thanks for the post John. I like this topic because I actually enjoy the sense that learning Chinese is hard. Well, most of the time I enjoy it.

I like your graphs, particularly the ‘Chinese’ curve for grammar. Recently I revisited 把 and 被 with a friend, determined to master what I first ‘learnt’ possibly four years ago. Now I think that 把 is the hard one – wah! so many ‘cases’. I have got to the point of realising that a proper understanding, allowing me to use a wide range of cases, is going to take me a very long time. [I really struggle with grammar in any language.] And I still get my tones corrected after so many years of speaking – that is kinda frustrating.

It’s been about 20 years since I last took a Chinese class, but I suppose it depends on the person. I never had a problem with the tones, and was able to make myself understood fairly well within months of acclimating to a Chinese-speaking environment. Thanks to computer input I have a hard time writing Chinese by hand any more. Typing it is easy, however.

Always fun to hear someone who’s “made it” write on this subject. I’ve noticed a lot of the frustration for new learners comes from their feeling: “If I’d put this much time into Spanish, I’d be hosting my own Spanish-language talk show by now!” but they still can’t do some basic things in Chinese. It’s a time issue for sure, but also a like trying to learn to juggle when there are a required minimum of 5 balls. “If I were just trying to juggle 3 balls, I’d have gotten it by now.”

Yeah I can understand that line of thinking.

(Incidentally, 5 balls is extremely hard. In juggling, the difficulty increases exponentially as you add balls. I can do 4 in several different ways, but 5 still eludes me, and I don’t want to put the time in anymore.)

I’m comparing Chinese to Latin, a language that I also tried to learn. With Latin my problem was the grammar, which is really difficult, at least for me. The few weeks with the course was just painful to me and I didn’t get any good feelings from it. Then I decided I’m not going to do any research that would acquire reading Latin and dropped the course.

I’ve also studied German and it has some tricky grammar points too. For me the grammar is the part that makes a language difficult or not.

With Chinese the grammar seems easy at first but I know it’s only getting more difficult. There are grammar points that doesn’t exist in any other language I’ve learned.

Chinese isn’t as difficult as it’s reputation says. It’s a hard work yes, but Latin and German have been more difficult to me than Chinese.

@Poagao “I never had a problem with the tones”

You’re a musician, are you not? In my experience, musicians don’t have any trouble with tones. So far as I can tell, tones are no different to singing or playing a wind instrument.

Yeah, I’ve heard that musicians have an easier time with pronunciation. I say we force Kenny G to make an attempt at Chinese, just to see what’s what.

That’s interesting… I’m pretty sure there’s some research on this. I’m going to try to dig it up when I have some free time.

(Incidentally, I’m a terrible singer, although the problem is more with my voice than my ear. Often I can hear I’m off key, but I can’t get on key.)

Chris, there may be something to that. I’m a musician and have not had to struggle with tones either. Memorizing characters, vocabulary acquisition, chengyu–that’s what kills me.

John’s point that juggling is a “foreign” skill is dead-on. In the case of Mandarin, the skill we acquire literally is foreign. And it’s that foreignness, that giant gap and lack of frame of reference to our native tongues that makes this so damn hard. Chinese would be much easier to learn if it weren’t so, well, Chinese.

(havent read the answers, wrote this only after reading the post)

Weird indeed!

Everything written in this post is strangely familiar to me and when i’m reading it, it’s just like reading my own diary or some nightmare notebook in which i’ve written the pains of chinese-learning. Chinese learning looks like a “mission impossible” to me, still but the strange part is that i never got trouble in the tones. I dont know why but i strongly assume that it is because i always see chinese-learning as a mere hobby and that way i never got frustrated when -after a painful, long long sentence- a chinese looks at me with blank eyes and is about to say “shen me yi si?” I just laughed and tried again. And again. And again… Now most chinese says i talk just like a chinese and my prononciation is nearly perfect but another strange part is that i cannot write or read (i can but so little that i dont even mention it) and my vocabulary is very, very poor. So where is the balance here? If i no longer have problems with the tones and i can chat with anyone ( using my little stock of words in chinese of course) why cant i still make better sentences or read and write? Why is my tones are very good but as a contrast, the other parts are poor and after hearing me talking, none believes that. Now chinese-learning looks even more impossible and i dont know how i’ll create that balance. I read of the posts and answers when i have time and try to figure out a way but on one hand there are chinese friends envying my prononciation and on the other, my poor vocabulary and reading-writing. No matter how i love chinese, it just looks as impossible as before. Anyhow, great post and website. I always wanted to give my thanks in words and now here i am. Keep writing!

John is the man if you need to learn chinese

he is the man with the plan if anyone knows

how to learn its John

Yeah, as the others have posted here, I’m a musician and I managed to get a grip of pronouncing tones pretty easily and I could distinguish tones pretty well, however the fact that the difference in tones had semantic value is what took me some time to get to grips. It just felt weird to associate a difference in tone with a pronunciation as a difference in meaning.

I’ve read a number of similar posts recently and found the discussions interesting, partly because I’m native Chinese. I’d say that Chinese is not that easy because many native Chinese kids find it easier to learn English than Chinese if they start learning both languages at the same age. Kids in Hong Kong don’t learn Chinese the ways I did. They learn it like it’s English, I’d say. So I’m interested to know how non-Chinese speakers learn Chinese and compare it with my old learning experience.

It’s true that Chinese is not a very structured language. I didn’t learn Pinyin, parts of speech and grammar. Neither did I have a textbook of Chengyu like the kids do today. All I did was the boring stuff: recital (背诵), dictation (默书), reconstructing sentences (重组句子), rewriting and expanding sentences (扩写句子) and reading comprehension (阅读理解). I had to learn classical Chinese texts, poetry etc when I started secondary school. The classical stuff was not too much because I was a science student and didn’t get to study Chinese literature or Chinese history after junior high. You can understand why the kids don’t enjoy learning Chinese much. Like John says in this post, it’s repetition of the basic skills.

Many of you have also observed that learning many Chinese characters doesn’t take you very far in mastering the language. This is both the disadvantage and beauty of Chinese: the flexibility and creativity that come with the combinations of the characters. Many 2-character words have become standard usage for more than thousands of years and we all learn them by heart. I guess that’s one of the main reasons to practice dictation. Chengyu and other standard phrases came from great Chinese scholars, writers and poets who put the characters in such elegant ways that common folks have repeated them for centuries. The language itself is a way to carry our literature, culture and history. If you feel that there’s a lot of stuff in the language of Chinese which is time-consuming, I can only say that’s how it is. People learn “扑朔迷离” by using it even though they may not know it’s related to the story of Mulan (花木兰). “醉翁之意不在酒” has become everyday language although not many people may remember its origin dating back to the Song Dynasty.

Whether you know the origins of these phrases and Chengyu, learning how to use them takes time. If you are not immersed in a Chinese speaking environment in which people show you or even explain to you all these Chinese usages, you may still feel frustrated after getting the tones right. For me, I can still get what you are talking about if you put the characters in a meaningful phrase or sentence even though some of the tones are wrong.

Another frustration is that speaking, reading and writing are not linked in Chinese as Bertha mentions it. Most clergymen in Hong Kong can speak Cantonese without learning how to read and write Chinese. If you want to do well in all areas, especially in writing, you have to put in at least 8-10 years’ work. For all the posts I’ve read, I only get to read John’s writing in Chinese. The other bloggers may speak well in Mandarin. But I cannot really say whether they do well in Chinese until I read their Chinese writings. Chinese people talk about “语文”. It refers to both speaking (语) and writing (文). For native Chinese, it’s not good enough if they cannot write smoothly. That’s why it’s a big problem when many high school graduates in Hong Kong don’t write well. For non-Chinese speakers, it’s a matter of goal setting, I guess.

hey just wanted to say great post…I was born in the states in a chinese speaking household but pretty much stopped learning when I started going to elementary school. Its funny cause I can speak with decent pronunciation but with a vocabulary of a 5 year old (or maybe younger!)

In any case, I just came back from a trip to china and I am thinking about buckling down and learning the language for reals this time (after a few fits and starts) and your break down of “difficult” vs “time consuming” is very helpful. Thanks again!

This topic has interested me ever since at a Chinese teaching conference (and as the only non-Chinese, Chinese teacher on the panel) another panelist declared “Chinese is not difficult at all and in fact it is easy! We just have to make our American students understand this and then they won’t be discouraged.” After various similar comments I finally piped in: “But, wait, it really isn’t easy. It isn’t! If you try to tell your students that then when they find it difficult for themselves the only conclusion they can come to is this “easy” thing must be so difficult because they are just stupid. It’s better to prepare them for the hard parts and help them pace themselves.” John’s point about studying and studying and just trying to have faith it will all come together, rings true. I tell my students “I know some parts seem difficult, but trust me if you put time in each week, come to class, do the self-study/homework time you WILL learn the language. Sometimes it won’t feel like that’s true, but you WILL.” There is a retired woman about 65 years old who started Mandarin in our school in San Francisco over a year ago. She comes to class (only once a week), does the work outside of class and she is at the point of being proficiently conversant (chatty with errors, but speaking and understanding your day-to-day conversations). You CAN and WILL do it, you just won’t get immediate rewards like you will with Spanish (3 months in Barcelona and I was chatting away, not error-free, but certainly keeping up at a dinner party). The immediate reward you do get with Mandarin is the immense positive feedback and encouraging comments from native speakers. I wish I had a dollar for every “Waa, your Chinese is so good” I have heard (even when it wasn’t). Studying and speaking French is a distinctively different experience (with pronunciation that can be on par with Mandarin). Anyway, great post. One last point regarding musicians studying Mandarin, I can sniff one out within the first ten minutes of any first Mandarin class. As soon as I hear their pronunciation, I like to shock them with: “You are a musician I bet.” I posted on the “difficult or not diffcult” issue in “Does Chinese Suck?” (http://chitchatchinese.wordpress.com/page/2/), linked to David Moser’s hilarious rant, and John’s “Five Stages of Learning Chinese”

I have lived in China for 6 years. I have in that time studied chinese off and on although quite dillegently at times. Online, group and private tutors. I even have a chinese wife. Unfortunatly I am not a musician but maybe I should learn guitar to help my chinese.

My chinese is so bad chinese still compliment me on it ( A sure sign of really bad chinese). For me, learning Chinese is really hard. I have done some really difficult things before but they do not compare with Chinese. But as it is still more rewarding than being able to juggle I will continue!

[…] impurity, but all you can do is exorcise them slowly, one by one, by practicing your Chinese. Getting tones wrong is frustrating, and can feel like torture at times, but heaven awaits… (Heaven is, by the way, […]

John, this is as brilliant as it is encouraging. My wife and I have been studying Mandarin and encountering exactly the process of frustration and gain you cover here, but without identifying it as such. This post is a shot in the arm, and the change of mindset from “difficult” to “time consuming” rationalizes expectations in a very helpful way. I’ve been a fan of your work on Chinesepod as well–thank you for your brilliant and witty contribution to this field. I suspect there are many more who would say you’ve made the journey easier for a lot of us.

isn’t that picture the same as the one you used on your chinesepod profile?

i used to live in China cpod did help me get over the fear i had with the language, exposure really did help a lot and i couldn’t agree more John it’s difficult but very rewarding. however, being not able to talk to Chinese native speakers isn’t helping me in doing my homework. 🙁

[…] Why learning Chinese is hard, Not! Filed under: Language learning ideas — Leave a comment January 23, 2012 An article on WHY LEARNING CHINESE IS HARD. […]

[…] An article on WHY LEARNING CHINESE IS HARD. […]

Great post.

I, like many others, have found tones to be the most difficult part of learning mandarin, and even after one year studying in China, I still find them frustrating. My problem was that when I first arrived in China, I could read and write about a five hundred words, but couldn’t put a sentence together or understand anything (I blame my institute’s style of teaching for this. All exams focused on writing; they only spoke English in class and only made you say one sentence in mandarin each class.). When I started studying in China, I decided to ignore the tones and focus on getting sentences out. Big mistake.

By the 6-month mark, I could communicate and be understood, but I’d often have to clarify what I meant (because of improper tones). Even now, after half a year of trying to self-correct my tones, I can only say them correctly by myself and when reading, but once I have a conversation, it all goes out the door.

I think the most important thing to remember is that your fluency in Chinese is not determined by how fast you can speak, but by your tones, pronunciation, and grammar. I constantly have to remind myself to slow down and focus on the tones and at the very least get the correct tones for the most important words in the sentence.

John, you are simply wrong.

Chinese is brutal in its’ difficulty and your post blithely ignores the 40 or so aspects of Chinese that do not exist in learning Russian, Spanish, Italian, Hindu or any of the other 30+ languages commonly studied at the University level. If you are middle-aged you can just about forget it.

Two aspects:

1) You must live in China to learn Chinese. If you study at home, your accent will be incomprehensible when you travel to China and you won’t understand them beyond the level of a 3 yo child. If you study it in HS and Uni you will be barely capable to a toddler’s level when you travel there.

2) The time Chinese students put in to learn the language is 5X to 10X what you put in to learn English.

You: 10 years age 6-16, 1 hour a day, 5 days a week, 40 weeks a year. 2,000 hours or fewer.

Chinese Student: 20 years age 3-23, 2 to 3 hours a day, 6 1/2 days a week, 48+ weeks a year and they attend camps on Chinese and other subjects during summer and winter holidays. 15,000 hours or more. They attend school 15 hours a day 6 or 7 days a week.

Chinese take DAILY language instruction in Pre-K, Elementary, Jr High, High, College, University and for Research (MA and PhD) Degrees. You stopped after 10th grade. Your Chinese Doctor took language every day for his years post-high school. You did not do the same with English.

Mark Rowswell, Da Shan {the most famous foreigner in China}, has this to say:

“5 years for basic fluency, but with difficulty. 10 years to feel comfortable in the language. One lifetime is not enough to attain the level of a native speaker, unless you start before the age of 10.”

May I know where you got this citation? Thanks.

Probably from here

http://www.quora.com/Chinese-language/How-long-does-it-take-a-native-English-speaker-to-become-fluent-in-Chinese

[…] out this blog post by John Pasden which delves more deeply into the challenges of Chinese, and graphically represents […]

[…] It all started when John from WooChinese wrote that Learning Chinese Isn’t Hard. Then two days after another John from Sinoplice answered by reasoning Why Learning Chinese Is Hard. […]

[…] John Pasden on ‘Why Chinese is Difficult’ […]

[…] A roommate of mine wanted help translating the abstract of his thesis into English, and I was hesitant to help. One part of it was of course the selfishness of not wanting to spend time doing something with no direct benefit for me, but even more than that was my wholehearted belief that he could do most of the work on his own. His English isn’t fantastic, but by finding unknown words in a dictionary, using the forums at word reference, and making liberal use of google translator, he could easily create a rough draft which I would be willing to edit for him. At least, that is what I thought. He knew about these different languages resources, but he kept repeating that he wasn’t able to do it. It strongly reminded me of John Pasden’s story about trying to teach someone to juggle: […]

hmmm, I have only arrived in china recently and have started to learn this language (mandarin) but I really dont find the tones that bad. Yes it’s a pain remembering them at the beginning but producing them – i seem to be doing them with ease – hearing them is very easy for me and producing not too bad either.

Perhaps it’s due to the fact that I come from a musical family and have a good ear for tones (lucky me hahaha 🙂 and I also already speak 4( but all european) languages.

So tones? – they’re okay. it’s the vocabulary that’s annoying. there are almost NO words similar to western languages – think about words like ‘bank, market, metro, taxi, bus’ (all these are practically the same in all Western languages) (but also in Japanese !!) but in Chinese you have to learn ALL these from scratch which is annoying. Even words like Internet! Pain in the ass but oh well.

Characters? hahaha. .. i’ll let someone else talk about those… 🙂

I really like the approach to this article; the difficulty of time versus frustration really resonates. Probably everyone has already read this, but since I didn’t see anyone link to it in the comments I’ll risk being redundant:

http://pinyin.info/readings/texts/moser.html

I find all of their points to be well researched and based on experience- and thus a good damned rebuttal to everyone’s blithe comments that Chinese is easy.

Its not. Having had a musical background does make it better- all the research demonstrates that this is indeed a boon to language learners everywhere (also have you seen the research on perfect pitch and the Chinese? Their tonal language gives them a huge boost in the number of people with this amazing skill!) but I think I’ll be griping mainly on the writing system.

The speaking is hard, and subtle, and the syntax is vastly different from the Romantic/Germanic languages with few cognates to ease the way.

But the writing system, good god. I teach English in Taiwan, and I see the number of hours of homework students have here, simply copying and memorizing Chinese characters (yes traditional, this is a difference). Yet this task is completely isolated from composition and grammar, that comes later- simply learning characters over and over again- you can’t even begin to compare it to your English spelling tests in elementary school- its utterly divorced from phonetic components (radicals be damned, they’re as eccentric as English spelling but more so) And its quite depressing seeing them memorizing this arbitrary tradition-bound tripe.

Its fascinating, its beautiful, but so is sculpture and traditional weaving; if you have the interest, wonderful, but its ease of use and practicability is somewhat limited and certainly soaks up time that could be devoted to other areas of discipline.

If you think this is too vehement, consider the fact that native Chinese speakers are losing the ability to write characters due to their reliance on text- message/computer based writing, which is a kind drop down menu thing.

Think about this in English- if a few years of not writing the word ‘apple’ makes you forget how to write it, than perhaps the writing is the problem, not the legions of people who have forgotten the overly complex, elitist system that made it.

Chinese writing is a bit like the London underground, yes, its the oldest, but no one would argue it’s still the best because it’s still beholden to archaic, outdated systems that make it hard to innovate.

Chinese as a spoken language is hard, but not impossible, but the fact that its written system is entirely divorced from the its phonetic components is deplorable and makes the whole “live in the country and immerse yourself’ of limited use-I do speak from experience. (Although I will say it’s pretty exhilarating when you memorize this utterly strange pictogram and then see it in the real world. It’s really gratifying.

It’s a bit like the old proverb of the Irish.

God invented whisky so the Irish wouldn’t rule the world.

The same could be said for the Chinese writing system – imagine all that Confucius-derived discipline being directed into something truly useful-all that spare energy would be a true intellectual force to be reckoned with.

[…] I know, have had similar experiences. On his Sinosplice blog, John mentions “the horrifying discovery that no one in China understood my […]

Hey

I’m studying in China at the moment and was having one of my occasional ‘what the heck am I doing!’ moments, sinking to the bottom of my barrel of motivation after yet another late night seemingly not learning how to write characters! Followed by too much coffee induced insomina,

followed by an early start, now back at my desk doing to start again , and it now seems only a tiny fraction of the words seem to have stuck in any part of my brain.

So, Though Id see if a google search could reveal some sage like wisdom or at least something to help me with motivation for today’s quota of impossibilty, and remind me I am not loosing my mind for dooing this and this article did.

Not the first time so keep up the good work!

Ps. hopefully the exageration of my anguish is apparent, I quite enjoy life here with only study and running to concern me!

Cheers

Wayne

我认为中文不是很难,其实最难得不是白话文,而是文言文。汉语中的字与词是互通的,所以在不同的场合相同的词语拥有不同的意思。最重要的是,汉语的语法比较混乱,但是只要多沟通是能学好的!0.0

[…] It’s not that you can’t learn like a child, it’s that you won’t. You’re not willing to. Not because you aren’t committed, or aren’t smart enough, but because you’re an adult with a little bit of self-respect. And you get frustrated. […]

[…] for most foreigners, but your students have decided to learn Chinese. They probably already know it’s not easy. Even if your surname is particularly difficult to pronounce, it’s probably only one […]

Try learning German. You will re-discover what hard and frustration really is.

[…] Pasden (Sinosplice) puts up his take on Why Learning Chinese is Hard. In his classic thorough fashion, he includes a discussion of what “hard” means, […]

[…] Even John Pasden, who has lived in China for 15 years and speaks fluent Mandarin, called tones "the single most frustrating thing about learning Mandarin Chinese". After 1.5 years of learning Chinese, John realised that nobody could understand what he was saying. […]

[…] I know, have had similar experiences. On his Sinosplice blog, John mentions “the horrifying discovery that no one in China understood my […]

[…] I know — Python is sooo easy! But then, learning some simple piano tunes is easy too. So is juggling, really, or sub-one-minute Rubik’s cube solves, or… Yeah, that’s what I wondered […]

[…] yes, I would say that learning Chinese is hard. But it’s worth […]

[…] Fans of free language-learning app Duolingo have been waiting for a Mandarin Chinese course ever since Duolingo launched, way back in 2012. In the meantime, many languages with much less demand have been added, including Greek, Hungarian, Esperanto, and even High Valyrian. Could it be that tackling Chinese took a bit more thought then other languages (some find it challenging)? […]

[…] day, we were having a conversation (mostly in English) about what characters we thought were “hard.” It was interesting getting her perspective, because it was totally different from mine. We […]

[…] or that beginners can’t learn it. No no no no. I may personally feel that the language is kinda hard to learn, but Chinese is not bad at all when it comes to sentence structure in particular. BUT, it’s […]