Comic Reduplication Meets Historical Reduplication

“Reduplication, in linguistics, is a morphological process by which the root or stem of a word, or part of it, is repeated” (Wikipedia). You see reduplication in Chinese a lot, with verbs (看看, 试试), nouns (妈妈, 狗狗), and even adjectives (红红的, 漂漂亮亮).

You get reduplication is Japanese too (some of the coolest examples are mimetic), in words such as 時々 or 様々. As you can see, rather than writing the character twice, the Japanese use a cool little iteration mark: 々. Now if the Japanese learned to write from the Chinese, why don’t the Chinese use the same iteration mark?

According to Wikipedia, the Chinese sometimes use 々, but you don’t see it in print. This is true; what the Chinese use (only when writing shorthand) actually looks something like ㄣ. Ostensibly, because you never see 々 in print in China (or it never even existed in neat, printed form), it comes out a bit sloppily as ㄣ in Chinese handwritten form.

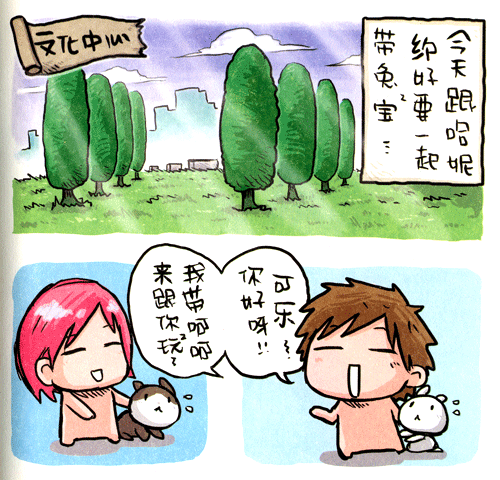

I recently read a cutesy Taiwanese comic called 兔出没,注意!!! Rabbits Caution about the lives of two rabbits named 呵呵 and 可乐 and their owners. In the comic, the author took a rather “mathematical” approach to reduplication. Look for 宝宝 and 玩玩 in this one:

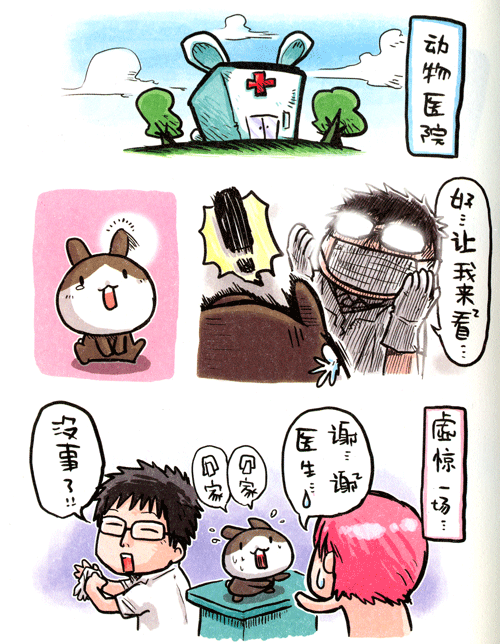

Look for 看看 and 谢谢 in this one (and don’t be confused by the 回 in 回家):

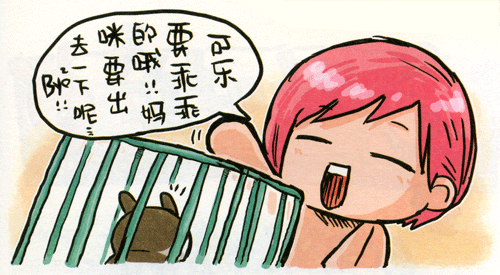

In this frame, even “bye-bye” gets the treatment:

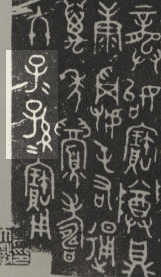

While cute, I figured this representation of reduplication was not likely original. I was quite surprised, however, to see an almost identical representation on Wikipedia dating back to 900 B.C.! The quote:

The bronzeware script on the bronze pot of the Zhou Dynasty, shown right, ends with “子二孫二寶用”, where the small 二 (two) is used as iteration marks to mean “子子孫孫寶用”.

Well, as they say, there’s nothing new under the sun, and history repeats itself. The weird thing is that 2 and 々 even sort of look alike, in the way that 々 and ㄣ do. 2 is 々 without the first stroke, and ㄣ is 々 without the last stroke. Meanwhile, the ancient Chinese iteration mark 二 bears a striking resemblance to the modern “ditto mark” used in modern English! (I’ll leave those for the orthographical conspiracy theorists among you to chew on.)

Great post. I am living in Malaysia and I see the squared exponent used frequently in Bahasa Malaysia but I haven’t yet noticed anyone using it in Chinese. I am going to ask around.

Nice post. I discovered the idiographic iteration mark a few years ago when one of my second-year Chinese teachers used it regularly on the blackboard. Most of my other teachers eschewed it, though, I’m not sure why. But, I have to admit, I like the “squared” notation better – it’s so obvious it’s brilliant!

Amazing.

I have seen teachers in Shanghai use the iteration mark (while telling us never to use it, “do as I say, not as I do!”), but when I see ㄣ all I can think of is ‘en’ in 注音符號/bopomofo.

My Japanese teacher went through 々 without talking about it or explaining what it was. I think it was because she considered it so obvious, something that everybody knew. Either that, or because all but 2 other students in the class were Chinese or Korean. Learning from linguists…

According to Wikipedia, the Chinese sometimes use 々, but you don’t see it in print.

In fact, 々can be seen in printed publications of old times, 1960s or earlier.

This is true; what the Chinese use (only when writing shorthand) actually looks something like ㄣ.

That might be case with Taiwan, where the bopomofo system is used. Mainlanders almost exclusively use 々.

That seal script inscription is very common on bronzes that were gifts from the king — I was just at the Palace Museum in Taipei a few days ago and you can see it on many pieces in their collection.

Wow! I’ve never seen this before, thanks for bringing it up? John,一个问题,我们怎么打字那个符号?

> 一个问题,我们怎么打字那个符号?

In Wenlin, you can type “s0/”, and you’ll be presented with a list of symbols. This one is in the second group (along with the Chinese quote marks “«»”, and the ever-useful tao symbol “☯”).

Or you can always Google “ideographic iteration mark”, follow the link to the Unicode page (e.g., http://www.fileformat.info/info/unicode/char/3005/index.htm), and cut-and-paste.

谢²!I like the “²” ones, too! That’s cute!

On the other hand, why are the kids in this comic all naked? Is the author promoting nudism?

“…the ancient Chinese iteration mark 二 bears a striking resemblance to the modern “ditto mark” used in modern English!”

Keep it quiet, John, or they’ll be asking for reparations and an apology.

Anyone else notice that “乖乖” wasn’t “乖²”? Actually, it wasn’t the only duplicated word that was simply duplicated.

hi John, nice post.

the iteration mark is just like “w” right rotate 90 degree.

btw, the pinyin for the iterational adjective are wrong, not mandarin anyway. the second “hong” is a light tone, the second “piao” is also neutral tone, “liang liang” is first tone.

i am native Chinese and majoring teaching Chinese as a second language, believe me.

Nice job on the new Android app! Very useful. I just wonder if it’s available to your China-based users….

“(I’ll leave those for the orthographical conspiracy theorists among you to chew on.)”

Oh, yes, it is all clues to the ancient Basque script. 😛

thanks! that’s both archeology and comicology!

one technical question: how do make these special reduplication signs print in your blog text? it is obviously not on your keyboard.

hobielover,

Yeah, there are more cases of that elsewhere in the comic. There doesn’t seem to be any rule to what gets “squared.”

peiwensen,

I just typed out 時々 in Japanese and copied the 々.

ilearnben,

Can you cite a source? I was originally thinking that was the case, but Wenlin had both 红红的 and 漂漂亮亮 listed without any 轻声. A little searching doesn’t provide clear support for your case, and the situation seems rather complex. I’m not saying you’re wrong… I’d just like to read up on it.

I’ve also seen a 2 put after a word to indicate repeating the word in Indonesian, although i don’t think it is officially part of the language

I once heard of one guy named Jimmy, who’s real name was Lin Lin Lin. His family name was Lin, his father’s name was Lin, but his grandfather wanted his name to be used as well, so they threw in a third Lin. I know that the two characters in the first name are the same character, but they might not be the same as his last name.

Anyway, he hated being called by his real name, but when people did that, they called him “Lin cubed”. And wrote it as Lin^3.

Ha! That’s great. So it’s 林林林?

While it could be abbreviated as 林^3, you could get creative and do 森森 or 森².

[…] Mandarin it’s an almost juvenile marking, used to indicate “cuteness” or […]