IPA for Chinese Children

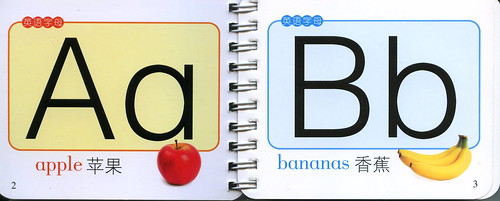

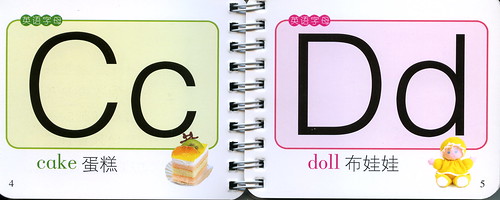

Teaching children English is important in countries all over the world. China is no different. Here are some scans from a little book designed to help teach Chinese children the alphabet:

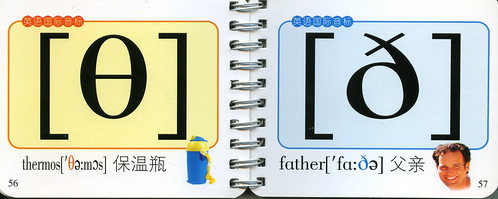

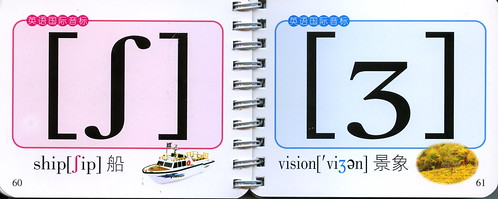

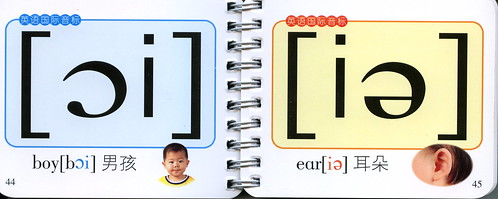

And once they’re done with that, why not teach them the international phonetic alphabet (IPA) as well?

Yikes!

Seems like a great idea, to me. I wish I’d been taught the IPA when I was a kid. Like the lack of the metric system, it’s something else I’m embarrassed of about my country.

I kid you not, I bought this exact same book for Charlotte about a couple months ago at the Shanghai Book Fair. Her verdict? The pictures are too small.

I teach English in Shenzhen and my students are always asking me to write words out phoentically for them. As a native English speaker I don’t remember ever learning how to do this! I always just refer them to te dictionary or their Chinese English teachers, who are apparently also up on their phonetics. I just don’t get it!

I still don’t know IPA either. I mean, I refer to it every now and then, but I just have in my head some arbitrary idea of what an upside down e sounds like. I could probably use this book.

IPA in China? Where? And to think, this whole time I’ve been drinking that crappy Tsingtao lager.

CHinese everywhere seem to know these, I never learned them and it is almost foreign when I try to read them.

Klortho: no disagreement on the metric system, but I don’t think the IPA is routinely taught in any Western country. It seems to be a Chinese thing.

IPA was a huge part of our esl school in Chengdu. I think it's good for them to study it the same way that us learners of mandarin should know piniyin.

In the textbooks for French and English we used in our school in Switzerland, the pronunciation of words in the word lists was indicated in IPA. This helped, especially with the English irregularities.

We didn’t learn IPA upfront, but after a time of seeing it besides the words and with the pronunciation in mind, we more or less learned what a certain IPA symbol meant and could apply the knowledge to new words.

IPA is also used in every dictionary, which helps a lot.

Actually, many Chinese learn some modified version of the IPA. For example, this book is either written by someone speaking a dialect I have never heard of or they have modified the way they represent vowels. [i] should sound like the vowel in sheep, but they seem to think ship is pronounced the same way. The ‘short i’ should be written [I]. has the same problem.

Also looks like they were transcribing an r-less dialect that would not be standard in GB or the US.

i’ve this argument with Tianjiner friends a few times: they try to tell me that English has its own pinyin, and I tell them it doesn’t, we just learn how to spell. They never believe me, and finally reach for their dictionary and point to the IPA stuff. When I tell them we never, ever studied that ever, except my wife who did a stint as a singing major in college, they get the greatest look on their face, but I’m not sure how to interpret it.

I’m actually trying to wean my Chinese students off using IPA – I guess they find it useful when they first start learning, but at the same time I have students who know all of the IPA sounds pretty fluently, and their English pronunciation still sucks because they haven’t spent half as much time actually studying real, natural English pronunciation.

I never understood the point of IPA… International Phonetic Alphabet. I guess it helps with pronunciation but I mean… why not learn Phonics. Most of my students just try and memorize the english words when in reality they don’t have to… they just need to look at the word and sound it out… but they can’t.

Once a student wrote a word in IPA on the whiteboard. I looked at it and thought.. this student knows greek?? what in the world??

I know a fair amount of IPA, on account of working for a company that publishes dictionaries.

The reason phonics doesn’t work is simple: it’s not universal, so it’s unhelpful for learning a second language. P in pinyin is not P in English, for example. IPA doesn’t have that problem. Instead it has the problem of being large and unwieldy. No one knows all of IPA (well, there are probably a few people with it memorised), and there are still spaces in the table for sounds that people could make but don’t appear in any known languages… yet. Certainly, a limited version of IPA is a good idea for kids learning English.

That said, yes, it would have been helpful if they’d used the correct symbol instead of “i”, though Micah’s concern about the dialect is misplaced–that’s RP, so it is ‘correct’. The problem is no one speaks RP much any more. I have this problem with Oxford dictionaries. Whoever does the IPA for them clearly hangs around with the cast of the Upper-Class Twit of the Year sketch a lot. Check out the OED’s entry for “electric”, for example.

I learnt IPA at primary school in Australia for at least one semester when I was around 11 years old…so about 20 years ago. I don’t think it was on the actual curriculum, but we had an old fashioned teacher who taught us about it. We never learnt it from any other teacher though.

I never saw it again until I got to China and started teaching English and kept having students ask me what the phonetic way of writing words was….of course I had no idea, so they were alsways saying that I must come from a backward part of the country where no one goes to school.

We had to learn IPA in the pronunciation class for my MA TESOL degree. It is somewhat useful for explaining differences in pronunciation, but as for learning it myself, it was a big headache and I just learned enough to pass the test and forgot it just as quick. I usually ask students for help. The upside down e is called a schwa.

I saw the handy book and thought it might be nice to grab a bunch of those books and sell them at astronomical prices to American students trying to learn IPA. Good stuff…. but teach kids phonics not IPA. Teach them how to read, not how to read a dictionary. From what I gather, the Chinese have not got on to the idea of phonics teaching.

Micah,

Are you actually going to teach your daughter IPA??

My opinion is that while IPA is clearly a valuable tool to linguists, and may be helpful to learners in some cases, it’s largely unnecessary for learning a foreign language. It’s much better to have native speakers as models (either live humans or using audio or video media).

I would guess that one of the main reasons that China has so enthusiastically embraced IPA is that it has been relatively poor for so long, relying largely on printed materials rather than the more expensive native speakers or audio/visual materials.

In any case, I see no reason to teach IPA to a toddler.

The problem with teaching Chinese students IPA is that they get in this mindset where they have to memorize every word and its IPA before they can read it, and the English language is just too chaotic for that to work. Hand a Dr. Suess book to a studious 6th grader and watch how quickly they get confused. The key is to teach them to sound out new words and guess at the meaning in context instead of reaching for the dictionary, to muddle through well enough to communicate.

The other problem with IPA is that it makes English pronunciation seem far more regular than it actually is. In actual speech, we tend to drop sound and run words together, not to mention the different pronunciations that come from different dialects and people just playing around with the language. Once you teach your students that most of the time “How are you doing?” actually sounds like “How ya doin?”, and why, they aren’t so intimidated by movies and music, and can spend more time actually learning the language than sweating the details.

I was taught IPA at grade five (twelve years old) in Sweden, probably in Swedish class, but I do believe it was used in English class as well.

@Ben,

Ha, that was my first thought when reading the title, hell if someones making an India Pale Ale in China, I dont care if they market to kids, I’ll still buy it!

Nah, I bought it for the alphabet: finger-tracing, use as flashcards, to hang on the walls of her room… the IPA had nothing to do with it.

I never learned IPA. Isn’t it kind of unnecessary for children learning English to learn that? I mean, it only helps when you’re using a dictionary that has IPA pronunciation. It won’t be useful when you are actually reading English. I suppose it’s true that it’s the same as people learning Chinese learning Pinyin, but it still seems a bit odd.

I haven’t learnt IPA at school, but it kind of came along with the English learning. Often we had to read texts at home and then read them out loud in class. Thus, using dictionary with IPA transcription was the only possibility to get it right – there were no tapes available. Regarding the book above, I find it really weird presenting a soung with viSIOn instead of for instance pigeon… And yes, the drawings are definitely too small. I’d rather engage my kid into making this kind of alphabet / IPA pages ourselves together – this would be some playing, family building, creativity and learning together 🙂

Hrmm I just don’t see the point of learning another alphabet to accomplish the same goal. It would be like me learning zhuyin (the taiwanese version of pinyin) on top of learning pinyin. There’s no point because they both are used to spell the real words that come together when you link a few of the symbols together. The real words in the case of mandarin being the hanzi (trad or simplified).

I do prefer American spelling to British spelling though (in most cases) when I am trying to help someone with their english even though I spell natively with the British standard because British english sometimes confuses the ‘sounding out’ process.

Nevermind the pedagogical issues, the typesetting is atrocious. The special IPA symbols are clearly serifed, but the [i] is sans serif. This is something I’ve actually noticed as being more common with multilingual signs in China, where the missing letters from the Chinese font would be substituted with some omni-unicode font (thanks to the ingenuity of modern computer programming). In this case, it would appear that the root font is missing the special IPA character-set extensions, and so forced the computer to select them from another available font.

@light487: As cute as your analogy is, learning the IPA for English isn’t in fact the same thing as learning zhuyin on top of pinyin. Zhuyin and pinyin have a one-to-one correlation, meaning you can easily map each glyph from one system to another without any ambiguity. (Although if you want to get really technical, there are some subtle differences of select words between Beijing Mandarin and Taipei Mandarin, such as Beijing’s “shen2me5” and Taipei’s “she3me5”.)

English, however, is largely traditional in its spelling, regardless of whatever standard you choose (British, American, Commonwealth, etc). Take the basic example of there being only 5~6 vowel letters (AEIOUY) to represent the 12~13 basic vowel sounds in English. Clearly you have a mapping issue. Now, consider the two following examples:

1. Did the amoeba see Caesar seize the seas?

2. look in the boot for the elegant era.

In 1., we have “oe,” “ee,” “ae,” “ei,” and “ea” (ie, five distinct vowel pairs) to all represent the same vowel sound. Conversely, in 2., we have “oo” representing two distinct vowel sounds and “e” representing at least three distinct vowel sounds. Given time, I can also find similarly sufficient examples to illustrate the mutability of the correlation between consonant letters and consonant sounds in English spelling. (Even the “th” in the phrase, “the theatre,” or the allegedly “hard” and “soft” C and G would suffice, not to mention the exceedingly contrived example of “ghoti” to represent “fish”.)

For any second-language learner of English, how would you best represent the identicality or difference between these combinations? There’s a convenient alphabetic system called the IPA that does exactly that. Now, whether teaching the IPA to children has any pedagogical merit is another discussion, but my point is that learning English and IPA isn’t exactly “learning another alphabet to accomplish the same goal.”

@Seralt: Nevertheless, the fact of the matter is that the Chinese use the IPA as a crutch and nothing else. I teach ESL in China and today, with my college freshmen, I wrote the word “rate” on the board. I said, “how do you know this is pronounced “ray-t.” They said, “because the yinbiao (IPA) says so.” If they see a new word, they have no idea how to use it. Although your examples are valid, there are many words, I’d dare say most words, that follow a certain set of rules rather closely. The deviation most likely comes from the innumerable amount of influence that other languages have had on English. Be that as it may, I have students in their 20’s now, who can speak English rather well, but have no idea how to spell a word or how to read a word they’ve never seen before. They’ve become so dependent on the IPA, that they think of English words just as if they were Chinese characters — pictures to be memorized for their appearance.

@Josh: That’s hilarious! Although I have TESL certification, I’ve yet to have the opportunity to use it overseas. Reading the other comments, I found it fascinating that they do exactly as you say — treat English words as indecipherable clusters of pigment (or pixels) that come with IPA pronunciation aids. I think you’re also right about the general orthographical patterns in English; although the spelling is historical, the sound changes in English are largely uniform, so mapping contemporary pronunciation to historical spelling isn’t too bad. The “ghoti” example fails in this respect because “gh” as “f” only occurs at the end of a syllable, after a back vowel, and “ti” as “sh” only occurs if another vowel follows it. (like “minutiae”, “location”, “substantiate”, etc.)

You’re also right that most of the deviation from the spelling-to-speaking pattern is a result of adopting foreign words. Others seem to come from the mysterious process of natural evolution of words (like how “love” and “move” no longer rhyme, but given the rhyming scheme of renaissance poets, it would suggest that they did at some point). Generally speaking, does the government/schools have a preference between British or American standard in Chinese classrooms? (for either spelling or speaking)

If the IPA was standardized as the world’s official alphabet, people will learn foreign languages faster – especially those using non-Roman characters like Chinese, Devanagari, and Thai.

Personally, I have a hard time pronouncing Chinese using the PinYin.

In fact, if this was pulled off, the various languages in the world will simply appear like local “IPA” dialects.

We should still keep tab on the non-Roman characters though because they’re our Cultural Heritage, needless to say.

I am currently developing a curriculum to teach it to my elementary school students. I think Seralt has a very good point and I think it is important for the kids to have some way to represent different sounds spelled the same way or same sounds spelled differently. I plan on only using it for the vowels.

I spent the last 4 years out of 5 (10 x Semesters) Teaching in China. These final Eight Semesters were primarily spent

helping Chinese College and university students improve their ‘spoken’ English. I was impressed they had been introduced to the IPA (International Phonic Alphabet) Phonemic Symbols at some point in their Schooling It seems they were shown the American Set of 40 Phonemic Symbols. Being British from Bournemouth in the UK, I showed

them there were 4 EXTRA Phonemic Symbols for British English compared to American English. (Since there is an extra vowel in British English, there is a corresponding increase, in three extra ‘Dipthongs’).

Chinese English Teachers have not learnt HOW to Teach Chinese Students HOW to make the SOUNDS of EACH and EVERY Phonemic SYMBOL in the Chart.

I particularly like the Phonemic Charts of Adrian Underhill:-

http://www.macmillanenglish.com/pronunciation/interactive-phonemic-charts/

Pronunciation Skills Videos – 39 videos about pronunciation skills

http://www.macmillanenglish.com/pronunciation/videos-with-adrian-underhill/

Adrian Underhill demonstrates why it’s important for native and non-native teachers to take a practical approach to teaching pronunciation.

This series examines in detail the Phonemic chart, the three levels of pronunciation, the physicality of pronunciation

and the ‘muscle buttons’.

We then have some recommendations for native and non-native pronunciation teachers and the best way to help English students with unfamiliar sounds.

Following up we have a series of videos on using the Phonemic chart to teach pronunciation of particular sounds in a very interactive and engaging way.

Download the FREE version of Sounds: Pronunciation App:-

For Android devices:

https://market.android.com/details?id=com.macmillan.app.soundsfree

For iPhone/iPad/iPod Touch:

https://market.android.com/details?id=com.macmillan.app.soundsfree

For teaching English pronunciation to people who are non-native English speakers, all speaking one common language say L1, I first find out how many of the 44 English sounds (24 consonant and 20 vowel sounds) are not present in L1. I then use special symbols (from IPA) to denote those sounds missing from L1 speech. So, this results in a localised L1PA (L1 Phonetic Alphabet) with exactly 44 symbols. Normally, an L1PA uses about five to eight new symbols which the speakers of L1 have to learn to transcribe pronunciations of English words employing L1PA. and read from a localised pronunciation dictionary for L1 speakers. I have done it for Bengali, Hindi, Nepalese, Bahasa Indonesia and Pinyin. With the help of a computer program (IPA to L1PA converter) I have generated the RP pronunciations of 30,000 commonly used English words. The first three have been published and the other two are available in electronic form,