04

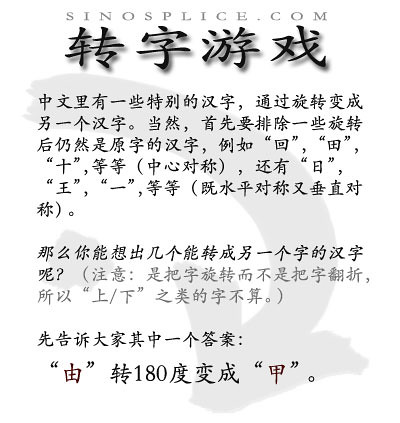

Apr 2005One character said to the other…

I was recently introduced to a cute collection of Chinese jokes based on the small differences between similar Chinese characters. Some of them can even be appreciated without much knowledge of Chinese. I’ve translated a few of those below.

> 个 said to 人: I can’t keep up with you youngsters, and I can’t get anywhere without my cane.

> 日 said to 曰: Looks like it’s time for someone to go on a diet.

> 比 said to 北: Come on, now, you’re a couple! No more of this ridiculous divorce talk!

> 人 said to 从: You guys still haven’t undergone the separation surgery?

> 木 said to 术: Don’t think you’re so hot just because you have that beauty mark…

> 尺 said to 尽: The results are in, sis. You’re going to have twins!

> 由 said to 甲: Doesn’t practicing One-finger Zen make you really tired?

(Read the full list in the original Chinese.)

02

Apr 2005What is One-Finger Zen?

Recently I came across the term 一指禅 in my Chinese studies. I asked my tutor about it. She said it was a mystical kung fu secret developed by the Shaolin monks. Using this technique, a monk can do a “handstand” using only one finger. Supposedly he can keep this up for several minutes.

An English search for “One-finger Zen,” however, turns up a different story. Unsurprisingly, information about Zen in English is normally about Japanese Zen (rather than “Chinese Zen,” or Chán). I found this story, which I remember hearing in Japan when I studied there:

> Whatever he was asked about Zen, Master Gutei simply stuck up one finger. He had a boy attendant whom a visitor asked, “What kind of teaching does your master give?” The boy held up one finger too. Hearing of this, Gutei cut off the boy’s finger with a knife. As the boy ran away screaming with pain, Gutei called to him. When the boy turned his head, Gutei stuck up one finger. The boy was suddenly enlightened. When Gutei was about to die, he said to the assembled monks, “I received this one-finger Zen from Tenryu; I’ve used it all my life, but I have not exhausted it.” Having said this, he entered nirvana. [full text]

So it appears to be both a badass kung fu trick as well as a full Zen philosophy. I was pleased to discover that the Chinese have yet another interpretation, which was good for a chuckle.

01

Apr 2005Shanghailander!

I learned recently from the Shanghai Wikipedia entry that some people actually use the term “Shanghailander” in all seriousness, meaning “a native of Shanghai” (Google search). Don’t they know about Highlander?? This deserves to be made fun of.

30

Mar 2005Marco Polo Syndrome

In a recent blog entry, Sam of ShenzhenRen discusses what Justin of Shenzhen Zen has coined “Marco Polo Syndrome.” Justin’s definition:

> **MPS: the silent social killer.**

> Symptoms: exaggerated manifestations of superiority and exclusivity fostered by the delusion that the individual was the first and only foreigner to “discover” China. While it’s difficult to fathom how one can still engage in this egregious self-deception while standing under a glowing neon 20-foot visage of Colonel Sanders, it’s apparently not an uncommmon affliction.

> Cure? Apparently none, though foreign friends in Shenzhen also confirmed my findings through their own research.

My comment on ShenzhenRen:

> “Marco Polo Syndrome” — haha, I love it! Whatever it is, I can confirm that the phenomenon is alive and well in Shanghai as well.

> All of the explanations you offered sound plausible. I quickly came to a conclusion after about two years in China: There are two kinds of foreigners in China: freaks and cool people. I think there are more of the former.

> The scary thing is that I have caught myself exhibiting some of the behavior you describe! I’ve never told anyone to “piss off” or anything that extreme, but I’ve certainly ignored other foreigners I pass by. I’m not sure why I do it — I think it’s out of some kind of assumption that all foreigners in Shanghai are dicks. But there’s really no need for me to follow suit and act that way.

> So now I make an effort to at least smile at other foreigners. Usually they ignore me or frown back, but at least I’m not one of them.

A visitor named Ryan (the same one that comments here sometimes?) replied:

> I think part of the problem in Shenzhen is the fact that most people don’t come here to “see” China (and if they do they’ve come to the WRONG place). We have other motives for living here. I think this leads to (at least) two types of people who exhibit MPS.

> 1) The asshole foreigner is here on business. Perhaps unwillingly. You will often see him at Starbucks and overpriced bars. He may take a fork with him to restaurants. Perhaps he is focused on his job and not interested in meeting new people. Perhaps he realizes that most foreigners in China are backpackers or teachers and feels a natural sense of superiority, preferring to associate only with other people who wear suits.

> 2) The asshole foreigner has been in China a while and has gravitated to Shenzhen in order to make money, support a family, have easy access to HK, etc. I’ve noticed length of time spent in China used as a status symbol. Perhaps they look down on other foreigners, assuming they are new arrivals (as they often are). Perhaps, having been here a while, they have their circle of friends and aren’t interested in having more. Maybe they think they are so native that they aren’t interested in foreigners (this doesn’t describe me, but I do find myself staring at foreigners as much, sometimes more, than the Chinese).

> I used to be a friendly foreigner, but after being snubbed so often I now wait to be acknowledged before I will do the same.

Whatever the explanation, there’s certainly something going on. (Notice that it’s an anagram for another ominous acronym?) Check out Sam’s analysis as well as Justin’s original entry.

28

Mar 2005Adopt a Blog Update

Seeing as how the press has called attention to Adopt a Blog once again, I think it’s time to give an update. The program has been going for about a year now. So what is its status?

A lot of people liked the idea of Adopt a Blog. I got a huge response from people offering server space. This is great, because success of the project depends entirely on the generosity of such people. But the success of the project also depends on something else. *People need to come forward and ask for hosting.* That, for the most part, didn’t happen. As a result, the project did not succeed in getting many blogs hosted at all.

But even if there were a large number of “adopters” as well as “adoptees,” there are still a few other problems:

– Currently, e-mail is the medium of communication for matching “adopters” and “adoptees.” That makes a lot of work for one person, and it’s not the most efficient.

– If the program were to be very successful, I might get blocked. Noooooo, I don’t like that.

– If the program were to be very successful, I’d get a lot more traffic, which would give me bandwidth issues.

Therefore, it is my hope that some benevolent company overseas could champion this cause and host Adopt a Blog on their own servers. They would make themselves look good by supporting free speech online, all for a comparatively small investment. It would also be easy for the company to set up a discussion board, which would be a better way to make matches than e-mail. The company could also have the site translated (I’m sure it would be easy to find people to do it for free) without fear of any backlash.

Sooo… any takers out there?

28

Mar 2005AP

Note to Self: *When you know AP is calling you for an interview at noon, don’t go to bed really, really late, and don’t wake up right before the interview.*

An AP reporter in Beijing called me the other day about a story. It’s not a story I’m covering in this weblog at all; I don’t tend to write about politics. The story has been covered quite well, very early on, by ESWN.

In the AP article I’m quoted as saying, “**I want to move the big eye off me.**” Yeah, I really said that. Leave it up to my groggy mind to make vague references to *Lord of the Rings* with regards to the Chinese government in an AP interview.

The quote seems a little contradictory, though, doesn’t it? If I want less attention, why would I agree to an AP interview?! Well, it’s sort of a calculated risk. I was trying to give Adopt a Blog some publicity in order to get it moved to more devoted hands. And if ESWN doesn’t get blocked for all the things he writes about, I really don’t see why I should worry. Still, I’m paranoid.

So far the AP article has already earned me one new friend. I found this fan mail in my inbox this morning:

> I read about you in the Washington Post today. Tell me, what is wrong with your own culture that you feel it necessary to continue with your obvious European roots to perpetrate your people’s disgusting racist practice of cultural imperialism!?

> I hope that Public Security sends your racist ass right back to Florida! You obviously received a shitty education at Florida and probably spent too much time getting wasted at frat parties.

> Come to NYC’s Chinatown and we will show you how us Chinese here deal with scum like you!

It’s like this guy can see right into my *soul!* Amazing.

26

Mar 2005Chinese College Dorms

Here’s a photo comparison of some Chinese college dorms. (Sorry, none of these pictures were taken for the purpose of comparing the dorm rooms, so they’re not perfect.)

Some of the commonalities you will find are: no full mattresses, no hot running water in the room, one room, not super spacious. Students get hot water by bringing it in thermoses (see Hangzhou pic). There are public showering facilities.

Hangzhou

ZUCC, my former workplace, is definitely the nicest of the three. There are only four bunks in a rather large room by Chinese dorm standards. The bunks have decently thick pads. There’s running water (cold) in the room’s own bathroom, and a squat toilet. You can’t see them, but I’m sure at least some of the students have computers on their desks.

Unidentified Location in China

I believe this photo to be more typical of many dorm rooms across China. The “bed pad” is probably a woven mat. It’s hard to tell if that top “bunk” is actually a bunk or not, but by the “toothbrush cups” on the desk we can deduce that six students live in this room. The clothes you see hanging up are drying after being hand-washed. I’ve seen other (poor) schools in Hangzhou that looked like this.

Beijing

I actually stayed one night in this very room in 2001. I forget the name of the school, but the campus was located northwest of city center, within walking distance of the Summer Palace. (Don’t misunderstand; I’m not trying to imply that Tsinghua Universtity dorms or Peking University dorms look anything like this!) Note the pipes coming out of the walls. The light hung from a wire in the ceiling. The newspapers are pasted to the walls because the white paint is so cheap that it will rub off on you if you touch it directly. You can see the woven bed mat here. The white object on the upper bunk is a blanket, not a pad.

If you have pictures to add to the comparison, please e-mail them to me.

23

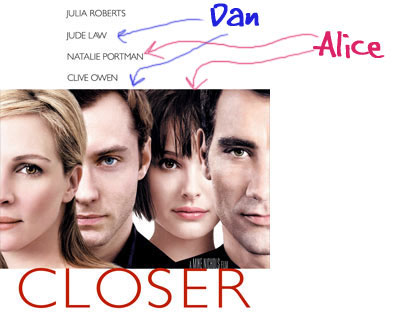

Mar 2005Closer Subtitle Surrealism

Everyone knows that in China piracy of American movies runs rampant. The USA acts all angry, and every now and then Beijing makes an attempt to do something about it in order to placate the WTO. Nothing new. I really couldn’t care less about Hollywood’s lost revenues. China’s pirated DVDs do affect my life in other less expected ways, however.

New American releases are obtained as early as possible and mass-produced in China quickly and cheaply. The earlier an eagerly awaited Hollywood title hits the streets in DVD form, the quicker it will be snatched up by movie fans. It should come as no surprise, then, that the quality of translation of the Chinese subtitles for these DVDs can be less than reliable. I’d say that the translations for Chinese subtitles on DVDs fit into three categories:

- Professional. These are usually obtained from an official source and are quite trustworthy. The Chinese is often natural and idiomatic.

- Hit and Miss. Whoever did the translation could understand a lot of the English dialogue and translate it with a degree of accuracy, but there are clearly some mistakes. Sometimes you can even tell what English word or phrase the translator thought he heard, based on the Chinese. This category can cause some confusion for Chinese viewers, but it’s usually good enough overall to tell the story.

- WTF?! For some movies (often the earliest, fuzzy camcorder pirated editions) the “translator” clearly did nothing more than guess at what the people are saying based on visual clues. This can be pretty hilarious if you can understand the original dialogue as well as the Chinese, but it must be very frustrating for the average viewer relying on the Chinese subtitles.

OK, so this whole situation is kind of funny… except for the fact that it can ruin my movie experiences. Why? Because if I’m watching an American movie with my girlfriend, she reads the subtitles. Conscientious boyfriend that I am, I can’t help but do periodic translation checks to ensure that my girlfriend is getting a decent idea of what’s going on. The more mistakes I notice, the more I pay attention to the subtitles so that I can clue her in on important dialogue. Often, before long I’m finding myself explaining the movie in Chinese instead of enjoying it. I guess I can live with that, though, since the movies cost $1 each.

But back to the absurdity of the whole thing. Can you imagine it? A Hollywood movie. The original dialogue has been chucked out the window, save for a few sturdy globs here and there. The rest of the dialogue has just been… made up. Fabricated. By some Chinese guy who’s undoubtedly poorly paid and under a lot of pressure to get the subtitles done now. And I don’t think I have to say that he’s unlikely to have a strong education in Western culture. That’s OK, he can still do subtitles for Western movies with themes ranging from terrorism to Catholic traditions to abnormal psychology. No problem.

The scary thing is that if he’s any good, some Chinese viewers might not realize they’ve been swindled. They may have gotten an alternate version of the story — which shared the same visuals as the original — that was convincing enough that they think they understood it as it was meant to be understood. “I thought the reviews said something about brilliant social commentary,” they reflect for just a few moments after finishing the movie. “Those silly Americans….”

Well, I can do more than just make suppositions, in this case. I actually transcribed a scene from a Chinese DVD copy of the Oscar-nominated film Closer. I transcribed the original English dialogue, but I also translated the Chinese subtitles into English for comparison.

Dan’s lines are in a rich blue. Alice’s lines are in a dark pink. Since the Chinese subtitles are only a shadow of their English counterparts, Dan’s lines translated from Chinese are in a lighter blue under the original, and Alice’s lines translated from Chinese are in a lighter pink under the original. I have added a 汉 at the beginning of the translated-from-Chinese lines just to keep it as clear as possible. You’ll find that it can be a little difficult keeping the parallel (occasionally intersecting) dialogues in your head at once.

(On the bus.)

A: How did you end up writing obituaries?

汉A: What kinds of things do you like?D: Well, I had dreams of being a writer…

汉D: I like drinking beer.D: But I had no voice — what am I saying??

汉D: But I don’t drink often. Also…D: …I had no talent. So I ended up in obituaries, which is…

汉D: I love singing. I can sing many songs.D: …the Siberia of journalism.

汉D: …including German folk songs.A: Tell me what you do. I wanna imagine you in Siberia.

汉A: I hope I’ll have a chance to hear you sing.D: Really?

汉D: Really?A: Mm.

汉A: Mm.D: Well… we call it “the obits page.”

汉D: Well… we don’t often sing.D: There’s three of us. Me, Graham, and Harry.

汉D: Because everyone is really busy.D: When I get to work, without fail — are you sure you wanna know?

汉D: Especially when I’m working. Extremely busy.(She nods.)

D: Well, if someone important died, we go to the “deep freeze.”

汉D: If someone died, we would sing the funeral hymn.D: Which is, um, a computer file with all the obituaries, and we find that person’s life.

汉D: Although I rarely sing, singing is something I can’t do without in my life.A: People’s obituaries are written while they’re still alive?

汉A: Do people like your singing?D: Some people’s. Then Harry — he’s the editor — he decides who we’re going to lead with…

汉D: Some people. Sometimes we get invitations [to sing].D: We make calls, we check facts…

汉D: Some are favors, some paid…D: At six we stand around at the computer and look at the next day’s page…

汉D: We’re all happy to do it; the money doesn’t matter. It’s great.D: …make final changes, add a few euphemisms for our own amusement…

汉D: It’s a kind of addiction. But it’s not like alcoholism.A: Such as?

汉A:D: “He was a convivial fellow.” …meaning he was an alcoholic.

汉D: I have a really strange friend. A homosexual.D: “He valued his privacy.” …gay. “Enjoyed his privacy” …raging queen.

汉D: But he’s content with his lot in life.A: What would my euphemism be?

汉A: Guess what kind of person I am.D: “She was disarming.”

汉D: You’re a cute girl.A: That’s not a euphemism.

汉A: I’m not cute at all.D: Yes it is.

汉D: Yes, you are.(Some time passes…)

D: What were you doing in New York?

汉D: What were you doing in New York?A: You know.

汉A: You know.D: Well, no, I don’t… What, were you… studying?

汉D: No, I don’t know. Are you… studying?A: Stripping.

汉A: Struggling.A: Look at your little eyes.

汉A: Your eyes are so pretty.D: I can’t see my little eyes.

汉D: Your eyes are even prettier.

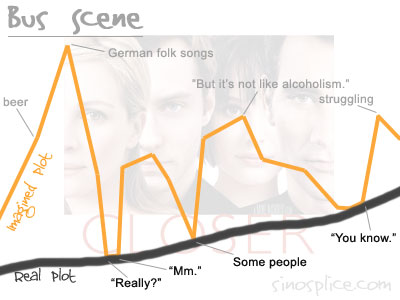

Impressive, no? For my own amusement, I have graphed the two dialogues below:

I should note that the whole movie was not this bad. This is a particularly WTF scene subtitle-wise. The subtitles of my copy of Closer are probably halfway between the WTF and Hit and Miss categories overall. Love stories are not so hard to figure out, but a relatively inconsequential bus ride with few context clues just unleashes the imagination of the “translator,” it would seem.

This example, I’m afraid, is by no means unrepresentative of the subtitle work provided by the hard-working DVD pirates. What are the ramifications of this? Well, it means every time I talk to a Chinese person about a movie we’ve seen separately, I feel a gap. Sure, we watched the same movie, but we may very well have experienced a somewhat different story. Exaggeration? Perhaps. But then again, maybe every scene of that movie was translated similarly to the scene above. You just don’t know. Furthermore, until this situation changes, the average Chinese citizen’s efforts at foreign film appreciation have been thoroughly sabotaged.

21

Mar 2005The Developing

I started my existence in China in Hangzhou, a very pleasant city as Chinese cities go. Now I live in Shanghai, China’s model modern city and an economic monster. I think it’s good to keep in mind that these cities are not representative of China as a whole. It’s good to keep in mind that China is still a developing nation. It can be remarkably easy to forget… that “developing” means a whole lot more than the public’s stubborn spitting habit. Pictures can be a good reminder.

Pictures of Zhuzhou, Hunan, China. Some of it looks very familiar. Some of it, thankfully, does not.

Don’t miss the comparison of Zhuzhou (China), Kochi (Japan), and Piscataway, New Jersey (USA). This is pretty old stuff, but I thought I’d post it now anyway.

18

Mar 2005Iron & Silk

In my junior year of college I decided that I wanted to go live in China after graduation. Around that time I picked up a well-known book called Iron & Silk by Mark Salzman (1987). It was the story of an innocent young American with a love for kung fu who went to teach English in China in the early 80s. It was a simple story.

[Sidenote: While I found the story to be a reasonably entertaining introduction at a time in my life when I knew very little about China, the one thing that put me off was the author’s claim to be fluent in Mandarin and Cantonese simply through four years of study at Yale. I didn’t buy it. But then, “fluent” is a very subjective word, and it’s frequently used casually in this kind of story.]A few weeks ago I found the movie Iron & Silk (1990) here on DVD in Shanghai, so I just had to pick it up. This movie holds the distinction of being one of the few movies where the author actually plays himself in his own autobiographical story. What makes this especially interesting is that we get to see Mark Salzman demonstrate on camera his alleged mastery of both Mandarin and kung fu.

The movie was OK. I’m no expert in kung fu, but I studied it for a few months once, and I’ve seen professional demonstrations, and Mark’s 武术 looked pretty good to me. His Chinese was also not bad (although it doesn’t measure up to the other Mark‘s).

After living in China so long, though, I couldn’t help but find the story Disney-esque. The interactions, the cultural lessons learned, the forbidden love (which was never allowed even a kiss)… it all just seemed so cute. Even the “dark side of China,” like when Mark was forbidden entrance to the compound where his teacher was because of a crackdown on “spiritual pollution,” seemed parallel to the level of horror you experience when Bambi’s mom is shot.

Now don’t get me wrong… I’m not saying the only cinemagraphic window into China should be movies like To Live or Blind Shaft or something…. It’s just that I don’t think this movie has much to offer those already acquainted with China besides a few smiles.

One thing that made the movie interesting for me was that although the original story took place in Changsha, the movie was filmed in Hangzhou. So I got to see imagery of Hangzhou c. 1990. Much of it looked familiar, but some of it reminded me of ugly streets in Beijing. It was fun seeing the protagonist put his moves on the girl at West Lake — a place where I’ve been on quite a few dates myself, back in the day. The movie even found the extras that played Mark’s English students at the Sunday morning English corner at 六公园 beside West Lake. I made the mistake of blundering onto that group only once, long ago….

Lastly, I’m a little disappointed that the title of the movie was never explained as it was in the book. The explanation that Mark’s kung fu teacher gave him, as I recall it, was that he needed to punch an iron plate many times a day to make the bones in the hand thick and strong. He needed to punch raw, rough silk in order to make the flesh of the hands tough.

I’d recommend this movie only to people who have read the book and are curious, or to people without much knowledge of China who are thinking of coming and teaching here, or are just plain curious. One should keep in mind, though, that China changes fast, so this movie is dated. Also, the English levels of Mark’s students are artificially high, and Mark is forced to conduct most communication in English (even with his Chinese teacher, for example) for the benefit of the English-speaking audience.

18

Mar 2005Reload!

I recently fixed some of this page’s HTML and CSS to be more standards compliant. The creation of this website was a self-taught process, coded entirely manually, and involved no shortage of trial-and-error experimentation. When I find out the proper way to do something, though, I try to update my code. I finally got around to it. If you’re a regular reader the CSS file is probably cached on your computer, so you’ll need to reload to get it to look right again.

17

Mar 2005新的功能

因为好像不少的人会看满老的blog文章并留言,我加了一个新的功能。在上面的菜单上我附加了一个“新言”链接。(这个称号是我自己乱取的,希望不是特别奇怪。)有空请看看。

谢谢大家的支持!

16

Mar 2005My trip, his lens

I was in Taiwan recently, visiting Wilson. I didn’t take any pictures; I left that to him. He has a great camera and better photography skills than me. Plus I’ve been on this extended “I’m too lazy to take pictures” kick.

I put together the Junk Food Review 2 from the pictures we took of Taiwan snacks, but it was up to Wilson to construct online abodes for the rest of his Taiwan photography. While most of us struggle just to “get the pictures online,” Wilson approaches his photo albums with a kind of artistic perfectionism, involving extended graphical negotiation with Photoshop for each image. He tells me my work on JFR2 added to the pressure.

Anyway, Wilson has finally unveiled his latest collection: Taipei. There’s another Taiwan album coming soon.

I should also mention that those who were interested in the human bite Wilson received in Taipei will find fascinating his photographic tribute to my blog entry “Taiwanese Men Bite.” The rest of you, of course, will be repulsed.

If you have comments on the photography or views expressed on Wilson’s pages, feel free to leave comments on Wilson’s blog. If you have comments or questions for me, obviously this is the place to ask. (Note: this weblog is not the place to debate some of the controversial political views Wilson presents within the album!)

UPDATE: The pictures are now also on Wilson’s Sinosplice mirror for your unblocked viewing pleasure. One new picture was also added.

15

Mar 2005Big Fish in a Small Pond

I’ve recently started using my Chinese blog for a new purpose: exploration of my Chinese readers’ understanding of their language. This can be attempted in many ways, but my first experimentation was with translation.

It all started when a friend asked me how to say “big fish in a small pond” in Chinese. He figured there must be a chengyu for it. It seemed to me like there should be too, so I got out my chengyu dictionaries. When I failed to find anything, I used Google. Still nothing. So then I decided to ask my Chinese readers. I gave my readers a short explanation of the expression (too short, in retrospect), and an example of its usage. Then I asked them: how do you say this in Chinese?

I got a decent number of responses, but none of them seemed to capture the meaning quite right. The results were very interesting, though, so I thought I’d share them. Here are some of the suggestions offered:

- “When there’s no tiger in the mountains, the monkey calls himself king.” (ɽÖÐÎÞÀÏ»¢£¬ºï×ӳƴóÍõ)

- “Choosing a tall person from among dwarves.” (°«×ÓÀïÃæ°Î³¤×Ó)

- “A crane standing among chickens.” (º×Á¢¼¦Èº)

- “Small temple, great monk.” (ÃíСºÍÉдó)

- “A magician meets a great sorcerer.” (СÎ×¼û´óÎ×)

- “Great talent put to little use.” (´ó²ÄСÓÃ)

I don’t think any of these match up perfectly. You can read my readers’ discussion of that in the comments if you read Chinese. What surprised me most was that the English expression implied a lot more than I originally thought, which disqualified a lot of the Chinese idioms, each carrying their own implications.

I’ll continue my linguistic explorations on my Chinese blog, and occasionally report back here when I find something I think is worth sharing.

14

Mar 2005Google-Friendlier

I just took some suggestions from a post on Scribbling.net to “help the Googlebot understand my website.” That’s why the title of each blog entry is now linked to, rather than having the “Link” link at the end of each entry.

Why? Well, Google associates the text you use to link to entries with the content of the links’ destinations. For example, if everyone with a website linked the word crap to microsoft.com, microsoft.com would become the number one search result for the word crap even though the word “crap” appears nowhere on Microsoft’s site. That’s why the words you use to link should be relevant. (It’s also the stuff Google bombs are made of.)

The word “link” is not at all relevant to the content of an entry. It’s essentially meaningless, just like “click here” or “here.” A surprising number of sites apparently don’t seem to care at all about this (Boing Boing, for example). I suppose those sites figure they owe nothing to the internet, or the budding Semantic Web, or whatever, and just want to do their own thing. I guess I’m more of a team player in this respect.

Anyway, Scribbling.net’s suggestions are worth checking out.

Also, if you read comments (including ones to old entries), you may be interested in the changes I made to the “Responses” box in the left column. Now you can click on [view] for a popup window of just the comments for that entry. This makes for faster comment viewing. If you want to see the whole entry as well as the comments that follow it (or if you just don’t like javascript), then click on the linked entry title.

13

Mar 2005Photography from Xitek

Xitek.com is a Chinese site which takes photography very seriously and showcases some of its members’ work. I’ve selected a sample of the more notable galleries currently online.

– 《矿工写真》: A collection of pictures of Chinese miners as a memorial to those lost in the Henan mining distaster.

– 粤西禁地 – 汉森病康复村: Photos from a leprosy recovery village in Guongdong province.

– 《大山之子》: 岜沙 is a village near Guizhou populated with people of the 苗 minority group.

– 香格里拉: This is mainly a bunch of maps, but I imagine they could be very useful if you’re planning a trip to Tibet and can read Chinese.

– 《中国模特之星》: Chinese model competition. The photographer seems to favor #3, at least in the beginning. I can’t say I blame him. (Don’t miss the links at the bottom of the page. There are nine pages in all.)

– 我的长城行: Ahhh, the Great Wall… forever photogenic. (Two pages)

– 行行色色之锦绣中华: This is kind of cool — a collection of links to photography posted in the forum, organized by geographic region, and complete with clickable map. (Warning: some of the albums linked to are not so hot.)

12

Mar 2005Document Contains No Data

“Document Contains No Data.” That’s the message I keep getting lately when I try to access my website directly. Those who live in the PRC know that this is Chinese for “this website is being blocked/filtered.”

I have been unable to access my e-mail for about 24 hours now.

I hate to do it, but I’m afraid I’m going to have to remove a recent post or at least some of its comments. Being blocked is just too inconvenient.

I’m doing some experiments, so certain posts/comments may disappear for a little while in the next few days.

If you need to e-mail me, I can be reached at my yahoo address (jpasden@).

UPDATE: OK, I think maybe I’m “the boy who called block.” I went into Movable Type via proxy and changed the Monologues post to “draft” form, which effectively hides it on the main page (but not in the archives, until I republish my archives). That seemed to solve the “document contains no data” problem, which led me to believe my site was being filtered. But now I think the “document contains no data” errors were random, and they just seemed to coincide with the hiding of the Monologues post.

I was also able to get into my sinosplice e-mail via webmail (not even via proxy). I thought maybe there was an “offensive” e-mail that was disallowing me POP access to my mail. If it was an offensive comment on my blog that triggered a block of my site, my e-mail comment notification would put the same keywords in my mailbox. So I got into my e-mail (waiting out intermittent “document contains no data” errors) and deleted everything I could. Shortly thereafter POP access to my e-mail started working again. Coincidence??

I have put the Monologues post back on the main page, and no comments have been deleted. Hopefully it won’t trigger further “document contains no data” and e-mail woes.

Hmmm… who’s paranoid now? If there are no further problems, it seems all this is attributable to network instability.

11

Mar 2005Getting All Academic

This morning I went to East China Normal University and sat in on the class of Professor 刘大为 from 8:30 to 11:00. It was a first year graduate course on cognitive linguistics. It was some pretty abstract stuff, touching on the nature of time and perception and what it means to cognitive linguistics, for example. The professor was surprisingly engaging, and I was able to follow most of it without much problem. Obviously, not having read (or even owning) the assigned text beforehand put me at a disadvantage… I didn’t find out until after class exactly what 类推 and 范畴 meant, exactly (they mean “analogize” and “category,” respectively), but I was able to follow OK anyway.

It surpised me that there was a foreigner in that class. From Macedonia! Her spoken Chinese wasn’t too polished, but she seemed pretty sharp. In a class of 18, she was one of only 4 people that responded to the professor’s questions during class.

After class I talked to the professor about my enrollment. I had spoken with him on the phone before, so he knew about me. He said they’d set up a time sometime soon to test me. I was really hoping to finally dispense with the vagueties and hear something concrete about the testing. No such luck. He merely said that my Chinese seemed very good, that I should have no problem, and even hinted that the testing was nothing more than a formality.

Then I talked to the lady in charge of admissions. She was also very nice, and surprisingly casual about the whole thing. “Oh, just get your application in to me sometime before May is over.” This is grad school! She and another teacher were also all complimentary about my Chinese, almost to the point of being annoying.

What they didn’t realize is that tests in written Chinese make me really nervous. Just before, in class, I had blanked on how to write the 普 in 普通. That’s not a hard character! Pressure seems to affect, more than anything else, my ability to recall and write out characters. That means I’m still nervous about this whole Chinese grad school admission thing.

Still, it looks like getting in is going to be pretty easy. I almost feel like it should be really arduous, and that they shouldn’t let me in so easily. Maybe it’s because I compare myself to Chinese students that go to study in the States, studying English for like 20 years before they get in? Yeah, I’m a bit short of 20 years’ study.

Speaking of academia, I was perusing my recent blog entries on the front page, and let me just say I can see why my family doesn’t comment much. The Chinese language/linguistic slant has been pretty strong lately.

Anyway, I’ll finish this nerdy entry off with a link to a really awesome post on a blog called 化境神似. I’ve been meaning to research this ever since 1999 when I first learned of the Communists’ unsuccessful 3rd attempt at character simplification doing research for my senior thesis. If you’re very into Chinese characters, don’t miss “Even Simpler Than Before.”

09

Mar 2005End of the Monologues

I was unhappy to receive this e-mail from Hank of The Laowai Monologues today. He didn’t mind me sharing it so that his anonymous readers might know what happened. All of his blog entries will soon be offline for good.

Today, ends my blogging here in China.

Without going into dramatics, or at least attempting not to, my blogging began to jeopardize my job, my marriage and my life. Let me give the final spill: it’s not eloquent, but I hope that many of you will stay in contact with me, and I want you–each one of you to know–that your support and comments through the last 2 and half years of my blogging career gave me moments of lucidity, sanity, and triumphs. Your emails brought me great satisfaction, great joy, and a real sense of connecting with humanity. Blogging was great for me; I never considered myself a real blogger; I mean, I never made daily blogs; I made lengthy missives which required I work and revise a great deal on them–some postings I thought humbly were quite good; others, in retrospect, made me cringe.

I am ending my blog because right now the internet is filled with moles, and in the People’s Republic of China, I feel that now and especially in the next few years leading to the Beijing 2008 Olympics, control and observation of websites will come under close scrutiny by the government internet police….

The bottom line: I do not want to risk losing my wife, my job, and be deported if push came to shove. Maybe that’s extreme; maybe I’m overreacting, but at this point, I don’t want to find out what exactly the consequences are, and its best to bow out now before I do jeopardize those things I have and love. This hits too close….

China is a lonely country for foreigners; the provinces even more so; isolation and scrutiny by the masses isn’t an easy thing to come to grips with. I definitely had my ups and downs, but one thing I know, as syrupy and mushy as it sounds, love is important: for your spouse or your students, and yourself and who you are, but never forsake those parts that make you human.

Please keep in touch!

Best,

Hank

The Laowai Monologues

March 9, 2005