09

Jul 2020Shanghai Down to “Half Mask”

Riding the elevator of my office building the other day, I suddenly noticed that only half of the people in the elevator had face masks on. I was the only foreigner in the elevator. There were 4 with none on at all (including me), 4 with masks fully on, and one with a mask on, but pulled down to under his chin. This is quite different from only two weeks ago.

Looking around on the street, I see a similar trend… Since face masks are required for riding the subway, you see a lot of mask-wearers on the street coming to and from Shanghai Metro stations. But when you get away from those spots, it’s much closer to half-half. In addition, people are much more likely to be wearing their masks in the morning than in the afternoon, and least likely after dark.

I’ve been observing who, exactly, is not wearing the masks, and I can’t really see any obvious trend… male/female, young/old, married/single, Chinese/foreigner… The 50/50 trend I seem to be seeing cuts across all the demographics. (I even see old people pushing babies in strollers not wearing masks.)

Obviously, these are just my own observations. I’m fairly observant, but I’m also not keeping records or running stats. But it is nice to see that things slowly returning to closer to “normal,” and it’s very interesting how long many segments of the population are clinging to the masks, long after it seems really necessary (especially compared with what’s going on in the US).

Stay healthy, everyone! 2020 is half over…

30

Jun 2020Shout-out to Terry Waltz

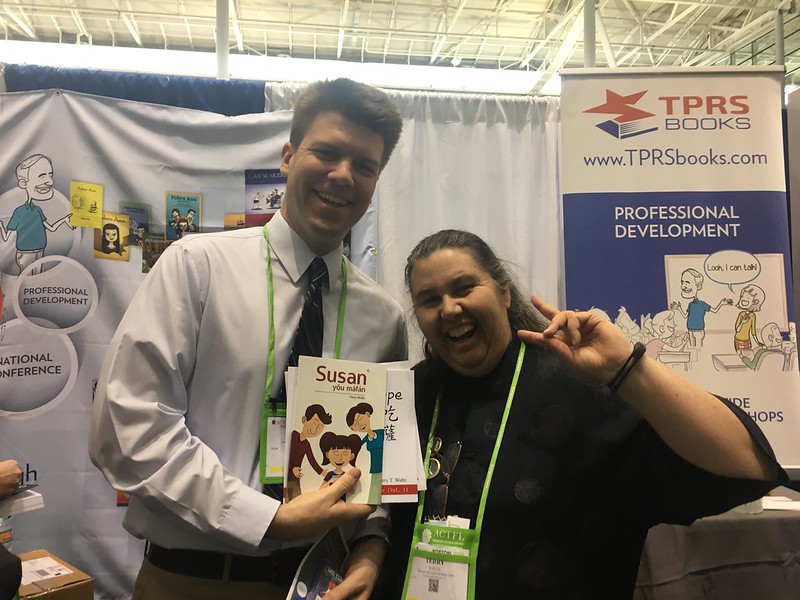

We recently had Dr. Terry Waltz as a guest on the You Can Learn Chinese podcast, and it struck me that I’ve barely mentioned her books on my blog before. It’s time for a bit of a spotlight!

I met Terry in 2016 at ACTFL in Boston. We had a great conversation about comprehensible input and Chinese graded readers. (I was there representing Mandarin Companion.)

Terry is all about improving literacy in Chinese (At the expense of handwriting characters, if need be), and has authored multiple books for early learners. She has pioneered a technique called cold character reading. She is truly a free thinker and an innovator, and the field has benefited greatly from her contributions.

Jared led the conversation in our podcast:

24

Jun 2020Happy Dragon Boat Festival

Thursday, June 25th, 2020 is 端午节 (Duānwǔ Jié), the Chinese holiday normally referred to as Dragon Boat Festival in English.

The Chinese name simply refers to the lunar calendar date of the festival, however. Not everyone in China goes and watches dragon boat races on this day… It’s much more common to just eat zongzi (粽子).

I like this zongzi-themed design:

I’ve also noticed a few bizarre, entirely off-theme ads during this holiday. Here are a few:

端午节快乐 (Duānwǔjié kuàilè)!

17

Jun 2020The Melon Pit

Nothing too special about this photo… Summer’s here!

“Melon” in Chinese is 瓜 (guā). In this picture we have:

- 西瓜 (xīguā) watermelon, lit. “west melon”

- 甜瓜 (tiánguā) muskmelon, lit. “sweet melon”

12

Jun 2020Why Discuss Black Lives Matter in Chinese?

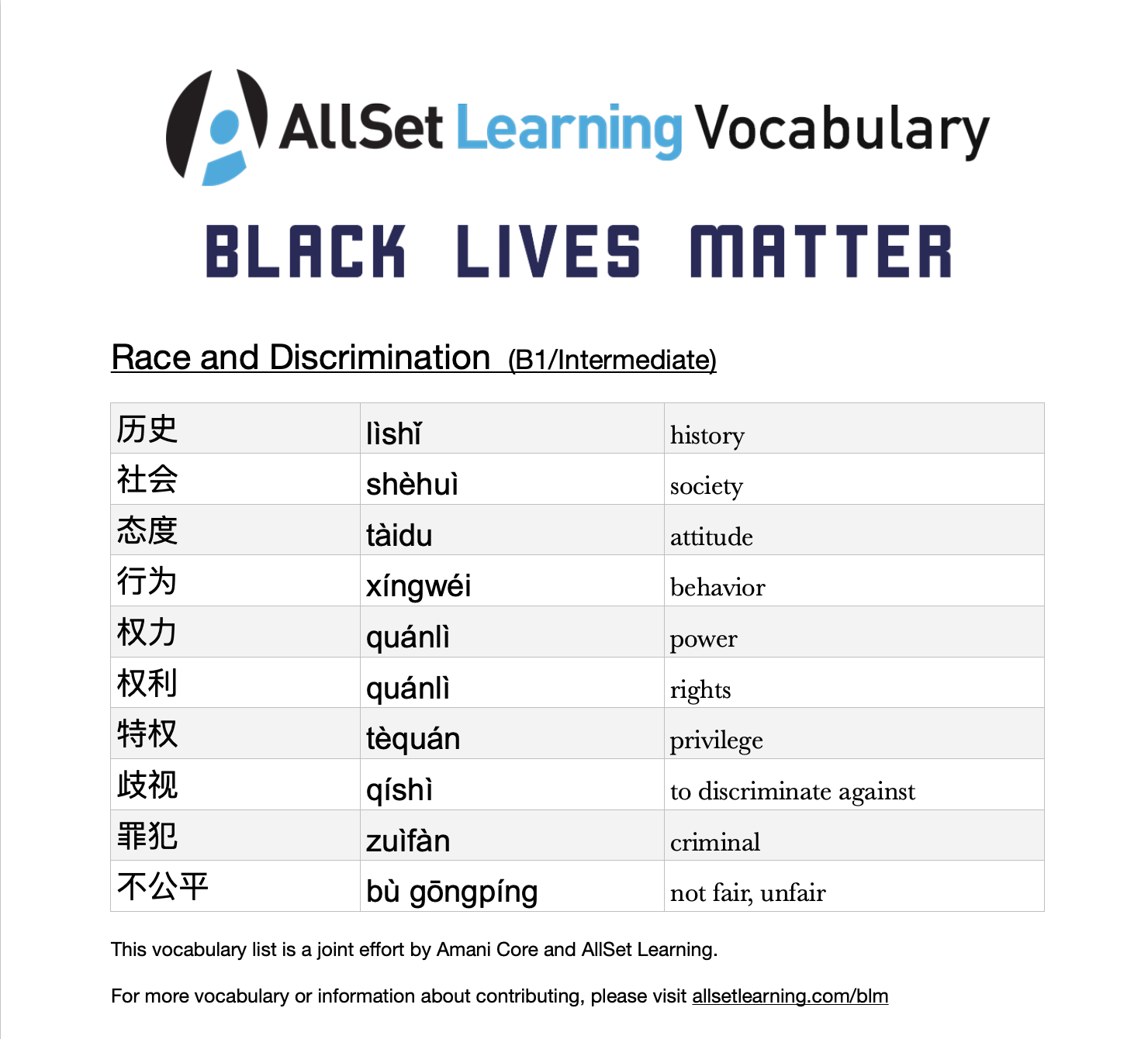

This week I worked with former AllSet Learning intern Amani Core to create a resource to help learners of Chinese discuss issues of racial discrimination, social injustice, and effecting positive change. You can find what we created at: Discussing Black Lives Matter in Chinese.

One question this prompted among a few readers was an incredulous WHY? Some readers didn’t see any connection between the Black Lives Matter movement and learning Chinese. I hope it’s obvious that there’s a very clear connection if the learner happens to be a Black American, and Black learners need Chinese language resources relevant to their lives too. But for now I’ll assume this is a white American sincerely asking, “why do I need to learn to discuss this topic in order to talk to Chinese people?“

Once your level in any language is sufficiently high, you’re going to want to be able to have at least some level of discussion on most topics. Quantum physics, watercolor paintings, the life cycle of a frog… it’s all fair game. You don’t need to be able to hold a lecture on the topic to be able to at least follow what the discussion is and say a few words.

But this topic is different. Black Lives Matter, racial inequality, social injustice… these topics go beyond just “something I should learn a for key words for at some point.”

The reason is because if you’re American (or even Canadian, European, Australian, etc.), Chinese people are going to ask you about this. Random Chinese people (drivers, hair cutters, old people in the park, etc.) as well as friends. They’re going to ask you because they’re curious, realize their knowledge of the matter is limited, and hope you can offer some insight. Sometimes the way the question is asked can be quite revealing. I’ve been asked about racism in America in all kinds of ways, including:

- You Americans sure are racist, huh?

- Why are Americans so racist?

- Why do Americans look down on black people?

- Black people in the USA sure have it hard, huh?

No white Americans I know aren’t going to want to just say, “yeah, we’re racist” and leave it at that. They’re going to want to offer at least a tiny bit of nuance beyond “it’s complicated,” even if their Chinese is not amazing. It’s a difficult conversation to have even in English, so it’s certainly not easy to talk about the realities of race in America in Chinese. But because Chinese people come from such a very different cultural context, and the average person really knows very little about this topic, there’s also less pressure.

So if you’re American (or find yourself talking about the US a fair amount) and are studying Chinese with the intent to talk to Chinese people in Chinese, I recommend you become a bit more familiar with this topic, starting at the intermediate level.

Our original blog post contains links to just three vocabulary lists at the B1 (intermediate) level, as images as well as a PDF, but there’s more to come. Vocabulary is only one part of language acquisition, after all.

For more advanced students and teachers, you’ll want to check out the online Google spreadsheet, which includes way more vocab. It will give you an idea of how we plan to expand this resource.

Please get in touch if you have constructive ideas, and check out Discussing Black Lives Matter in Chinese.

09

Jun 2020The Price of Eggs in China

That price is for one 斤 (jīn), which is 500 grams (the vendor says that’s 8 eggs).

So that’s 5.8 RMB per kg, or 2.7 RMB per pound.

2.7 RMB, at the current exchange rate, is US$0.38 (per pound).

Even if you’re not buying the cheapest eggs, you can typically buy eggs in Shanghai for less than 1 RMB (US$0.14) per egg.

2020-06-19 Edit: Sorry, people, my original eggs prices were off. Thanks to readers for calling it to my attention.

The real reason I took this photo, though, is as a reminder to learners that your written Chinese characters don’t have to be amazing works of beauty to get the job done.

Since I hardly write by hand these days, my own Chinese handwriting is pretty ugly too, but I don’t sweat it.

03

Jun 2020The Value of a Language Learning Homestay Experience

On our latest episode of the You Can Learn Chinese podcast, one topic Jared and I talked about was homestays for language learning. Jared hasn’t done a homestay, but he has hosted students in the U.S.

I did a two-semester homestay in Kyoto, Japan when I studied abroad from 1997 to 1998. I credit it for a big chunk of the boost my Japanese got that year. It was exhausting, but I became pretty fluent in that time. Even more impressive, 20 years later I hardly use Japanese in my daily life, but I’ve managed to hang onto that basic fluency. Occasional trips to Japan (and a little erratic studying) have been enough to keep it up.

Perhaps the best part is that when I go back to Japan, my homestay parents still treat me like family. Here’s us, reunited just last year:

How Long of a Homestay?

Clearly, the length of a homestay is important. One day or even one week isn’t going to make a huge difference in your language acquisition, even if it’s an interesting (and educational) cultural experience.

Unfortunately I have mostly just anecdotal evidence to base this on, but it seems like you need at least a month to really “get into” the homestay experience and make noticeable progress. At least three months seems ideal.

Another significant factor is that the homestay will likely be more interesting and less stressful if you’ve already been studying the target language for at least a year or so. Total beginners may not have a productive experience in a homestay.

But what does the actual research say about this?

The Research

The research is strangely inconclusive and unhelpful! Admittedly, there are a lot of confounding variables here…

- Some homestay families are just not that committed or “into it”

- Some homestay learners are super shy, or suffering badly from culture shock

- Some study abroad programs may be so full of classes that the homestay is little more than a place to eat and a place to sleep

- There are a million distractions as a student studying abroad, many of which could displace some of the value of the homestay itself

Still, there is research!

From The short-term homestay as a context for language learning: Three case studies of high school students and host families (Rivers, 2008):

…in quantitative studies of college-aged students abroad, the putative home stay advantage has been notoriously difficult to prove, perhaps in part because these students are interpreted by all parties (including themselves) as relatively independent young adults whose goals need not align with those of their hosts…. Our findings suggest that relatively advanced initial proficiency offers many advantages for interaction with hosts, but that students with modest initial proficiency can also develop warm and cordial relationships in the homestay if all parties are so predisposed.

From The Effect of Study Abroad Homestay Placements: Participant Perspectives and Oral Proficiency Gains (Di Silvio, Donovan, and Malone, 2014):

Although the study abroad homestay context is commonly considered the ideal environment for language learning, host‐student interactions may be limited…. Students and families were generally positive about the homestay, with significant variation based on language. A significant relationship was found between students’ oral proficiency gains and their being glad to have lived with a host family. Significant correlations were also found between students’ language learning satisfaction and their satisfaction with the homestay.

More recent research seems to be more positive. Obviously, this is not the year for study abroad, but if you’re considering making a homestay a part of your study abroad experience, my advice is to just do it.

Listen to the Podcast

If you’re interested specifically in the 5-minute homestay discussion, go to 36:20~41:36.

I’d love to hear other perspectives on homestay experiences, specifically how long your homestay was, and how helpful you think it was in improving your fluency. Please leave a comment!

28

May 2020Biang Check

I’ve noted before that my daughter (now 8yo) was a fan of the character “biang” (an unofficial character used to write the name of a kind of noodle in northwestern China). We’ve also pointed out to her that it’s frequently not printed out (just as it’s not in the text of this article) because computers can’t handle it. But it’s been a while since we thought or talked about the character “biang.”

Then recently my wife spotted this use of “biang” in the wild and shared it with our daughter:

Her immediate response was, “they wrote it wrong. It’s missing a 立刀旁 (刂).”

Aaaand, she was right:

We’ve created a monster!

P.S. Technically, there’s probably no true “standard of correctness” for this character, but the one she originally learned (same as the image above, but using simplified components 长 and 马) seems to be the most widely accepted version.

26

May 2020Wan Hui, the Anhui Character Party

The name of this restaurant is Wan Hui: 皖荟. It’s a pun on the word 晚会, which is sort of like “evening party” (or dinner).

皖 stands for Anhui Province, and is also one of the “8 great” types of Chinese cuisine. 荟 here calls to mind the word 荟萃, a flowery word for “assembly.”

This restaurant in Shanghai’s Changning Raffles City ( 长宁来福士广场) is not mind-blowing, but it’s still pretty special. Cool atmosphere.

I like these character fragment decorations on the walls:

The dry ice and purple lights are a cool contrast to the traditional Anhui-style walls:

As for the food, ummm, it’s OK, I guess? I’m not much of a 吃货 (foodie).

19

May 2020Masked Statues

A photo I took the other day in front of a (closed) school here in Shanghai:

When I saw these statues, it was at a time when it was unclear when elementary schoolers would be returning to school here in Shanghai. To me, the masked statues sort of represented a sort of permanence of the COVID threat. And yet, those masks can be so easily removed from those statues… and they will be.

Last Friday, we parents in Shanghai received news that primary schoolers will be returning to school on Monday, June 2. Furthermore, they’ll be letting out for summer vacation only a month later. I don’t think we really expected that.

A funny aside: on WeChat, when I see other parents of young children talk about putting their kids back in school, they frequently use the phrase 神兽归笼, literally, “the magical beasts return to the cage.” (If you do a search, you’ll find a bunch of posts about Chinese parents dealing with kids online learning from home.)

13

May 2020Dashan Explains His Chinese Name

In my last article on How to Choose a Chinese Name: 4 Approaches, I used the example of Mark Rowswell, AKA 大山 (Dàshān). Mark and I have a history of correspondence, so I decided to get in touch by email and get his take. He provided quite a lot of background info (much more than I was expecting), so I thought it would be good to share.

The following is our exchange, starting with his reply.

Mark (大山) wrote:

许大山 [Xǔ Dàshān] was the character name, but I dropped the surname when I took 大山 [Dàshān] as a stage name and then eventually as my all-purpose Chinese name. At that point I completely stopped using the name I had been given in Chinese class at university.

I never use a surname with 大山, as I think of it like “Sting” or something. It’s a standalone name by itself. And I always spell it as one word in Pinyin, which should be the convention for given names. It’s not correct to write it as Da Shan, as some people insist, because “Da” is not the surname. I notice you did spell it as “Dashan” in the article (but you did get “Rowswell” wrong, ha ha). [Since fixed!]

For “official use” it’s actually kind of arbitrary. My legal name is only what appears on my birth certificate, passport, etc. and that’s only in English. The Chinese name has no legal standing. But of course various Chinese organizations sometimes insist on using a Chinese name for official purposes. In that case, sometimes they take 大山, other times they insist on using 马克·罗斯维尔 [Mǎkè Luósīwéi’ěr]. I don’t really care, it’s just paperwork, so I let them use whatever they want. I just think it’s arbitrary because neither name is actually a legally registered name, and how you transliterate into Chinese can be quite flexible. I mean, there is a standard, official translation for “Mark” as 马克 [Mǎkè], but what is the official translation of “Rowswell”? There is none, so you can only follow general guidelines to come up with something like 罗斯维尔 [Luósīwéi’ěr].

Nowadays, when people use something like 啊啊啊啊啊啊啊啊 [Ā’ā’ā’ā’ā’ā’ā’ā] as their name, even with breaking convention by not having a surname 大山 is pretty conservative in comparison, ha ha

I replied:

大山 like “Sting”… Ha ha, that’s kind of hilarious.

I’m a stickler for proper pinyin most of the time, but I’m surprised I got your English surname wrong. Sorry! It was a typo and has been fixed.

Anyway, I had no idea that “official Chinese names” were so arbitrary. But that’s true of so many things in China… It all comes down to how local officials interpret and carry out the directives from above.I’d like to run a correction/update on my blog. Would you mind if I quoted your reply in this email? Few westerners have as much China experience as you!

And Mark (大山) replied:

Yeah, I’m kinda dating myself with the old “Sting” reference, and of course Dashan was always way cooler than Sting, but it seemed to be the easiest example.

I’m OK if you want to quote this reply. It’s all pretty basic stuff. The main reason “Dashan” stuck as a stage name is that it’s super easy to remember, and it has the added joke factor of implying the slang phrase 侃大山 [kǎn dàshān], which was particularly popular in the ‘80s and ‘90s. I think a third angle is that it’s a typical peasant name, which is strange for a foreigner. Because the Chinese names we are given when we start studying Chinese are usually very proper and cultured, even kind of poetic, or else they are a strict transliteration, it just seems funny when a foreigner takes a simple peasant name. That was part of the joke of the original skit, and the main reason the name stuck. I grew to like it because it’s down-to-earth and people find it relatable, so it matches the public image I was trying to portray.

Mark touches on a quite a few of the issues I brought up on my original post on Chinese names, so I figured this could serve as an interesting case study of sorts.

06

May 2020How to Choose a Chinese Name: 4 Approaches

Should learners of Chinese have a Chinese name? That’s a good question, but it’s not one that I’ll be answering in this article. Assuming that you feel you need a Chinese name, there are several approaches that you can take, depending on your preferences and your needs.

Foreign Name Transliteration

Transliteration means representing the sounds of one language as closely as possible, using the sounds of another language. My last name, “Pasden,” has been transliterated into Chinese as something like “Pa-si-dun.” Names converted into Chinese in this way have a distinctly foreign feel, and there’s essentially a set of “transliteration characters” used for the full text conversion. When a Chinese person sees a transliterated name of this sort written in characters, she immediately knows it’s a foreigner’s name, and she also knows to disregard any meanings the characters might have originally had. It’s just a string of sounds.

This is the type of name you get if you don’t speak any Chinese and are only accepting a Chinese name because you have to. For example, if you’re applying for a work permit in China, they will ask your Chinese name. If you don’t have one, the government worker will do a basic transliteration and use that.

Examples of this kind of name include:

- 路德维希·范·贝多芬 (Lùdéwéixī Fàn Bèiduōfēn) Ludwig van Beethoven

- 阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦 (Ā’ěrbótè Àiyīnsītǎn) Albert Einstein

- 贾斯汀·汀布莱克 (Jiǎsītīng Tīngbùláikè) Justin Timberlake

You’ll notice that this approach also results in the longest possible Chinese names. If your Chinese friends or co-workers actually have to use a name like one of the above, they’ll quickly shorten your name or give you a Chinese nickname.

Which brings us to the next approach…

Chinese Nickname

This approach is undoubtedly the most fun. Many Chinese people love to bestow cute Chinese nicknames on foreigners, and you’ll find that lots of singers and Hollywood actors have well-known Chinese nicknames (because no one wants to use those long, unwieldy transliterated foreign names).

As a non-Chinese, you’re going to have a very hard time coming up with anything clever on your own. These frequently develop organically as a natural result of interactions with Chinese friends, and if you like a nickname you hear, you can claim it as your own. (Just be sure you know what it means!)

Some examples of this type:

- 郭一口 (Guō Yīkǒu)

- 铁蛋儿 (Tiě Dànr)

- 大山 (Dàshān) — this one is less “fun” or silly; it actually came from the name of a character in Mark Rowswell’s first performance

Chinese Familiar Name

If a nickname is too informal or silly for your needs, but you’re not ready to go “full native” with a Chinese name, you might consider just choosing a Chinese surname, and then using the “familiar address” form built into Chinese culture which involves Chinese surnames.

This method usually uses 小 (xiǎo) or 老 (lǎo), plus a surname. This approach has the advantage of being fully culturally Chinese while still being easy, and not requiring full commitment to a Chinese name. This can actually be a good way to “get started” with your Chinese name: choose a Chinese surname, then add a 小 (or possible 老) before it. You can figure out the rest of your Chinese name later, after you’ve “tried out” the surname for a while.

Examples:

- 小潘 (Xiǎo Pān) — this is what my own Chinese name started as

- 老马 (Lǎo Mǎ) — this one sort of doubles as a nickname, since it literally means “old horse”

- 小江 (Xiǎo Jiāng)

Note that this is not a formal name, so I doubt you could use it for official registration purposes. Because it’s a Chinese form of address, don’t be too surprised if the Chinese official responds with a “that’s not an official name.”

Native-like Chinese Name

This is what most learners want: a name that sounds like a Chinese person’s name, and is not readily distinguishable from a native speaker’s name. Ideally, it also has a connection to one’s original name.

Some learners opt for a Chinese name that sounds as close as possible to their real English name while still sounding native Chinese. This doesn’t work well for all names, and when done poorly, can even sound like a semi-transliteration.

Other learners are satisfied with a few token similarities (begins with the same letter, for example) and just go with something “more Chinese” that they like. (This is what I did myself.)

It’s worth nothing that you don’t have to represent both your surname and your given name in a set way. I’ve seen lots of creativity in the way that people choose their names, including the following:

- Choose a fully native-sounding Chinese name (2 or 3 characters) that sounds kind of like one’s surname only

- Choose a fully native-sounding Chinese name (2 or 3 characters) that sounds kind of like one’s given name only

- Choose a fully native-sounding Chinese name (2 or 3 characters) that swaps the typical surname/given name order, e.g. choosing 周 (Zhōu) as a surname to represent “Joe,” and then choosing a given name that sounds kind of like Joe’s surname.

- Choose a fully native-sounding Chinese name that in no way relates to your English name, or does so in a subtle way related to meaning

- Choose a fully native-sounding Chinese name that integrates with Chinese in-laws, e.g. taking your Chinese spouse’s family surname

I’m not going to give lots of examples of these, because the whole point is that this kind of name sounds like a Chinese person’s name. So you might as well look at a list of native Chinese names.

One thing you need to take into account is the feel of the Chinese name, and you’re definitely going to need to ask a lot of native Chinese speakers how they feel about your Chinese name. Keep in mind that no single opinion represents all of the Chinese-speaking world, and expect a bit of conflicting information! Some feedback you might get is that the name sounds “too revolutionary” or “too traditional” or “too literary” or “too foreign” or even just 不好听 (bù hǎotīng: sounds bad!).

Get help from native speakers. (This is not something you can do entirely on your own.) Get lots of feedback. Find a name you love.

Special Mention: Jeremy Goldkorn

Jeremy Goldkorn, founder of Danwei.org and now Editor in Chief of SupChina, has a Chinese name which delights nearly everyone who hears it, but doesn’t fit neatly into any of the four approaches I’ve outlined above. His name is:

- 金玉米 (Jīn Yùmǐ) literally, “Gold Corn”

金 (Jīn) is a legit Chinese surname, but the use of the word 玉米 (yùmǐ) seems to fall into nickname territory, although it’s not entirely out of the realm of possibility that an actual native Chinese person could have this as their name. (I’ve heard some pretty bizarre real Chinese names in my time in China.) I think this name would be accepted by Chinese officials as a formal name.

The point here is: there’s room for creativity! My four approaches should be useful for a lot of people, but there’s definitely wiggle room for you to get creative and go your own way.

Podcast Discussion

I discuss this issue on the latest issue of You Can Learn Chinese podcast with my Mandarin Companion partner, Jared Turner. You can tune in here:

29

Apr 2020Jiong Ma with Russian Characteristics

This an old poster I never got around to posting before:

What makes the movie title unique is that it incorporates Cyrillic letters into its Chinese characters. I’d never seen this kind of thing before, so I liked it. I’m no expert on Russian, but I can recognize Д and Э in there!

Anyway, the movie is called 囧妈 in Chinese, Lost in Russia in English. It’s part of a “Jiong series” of comedies which I won’t go into but are easy to find.

21

Apr 2020Tone Pairs Online Audio Update

My Tone Pairs Drills have been online here at Sinosplice since 2006. I’ve been advocating this type of practice for quite a while, and my work with individual clients at AllSet Learning has continued to prove that tone pair practice really works.

Some time ago, the online audio for the Tone Pair Drills ran into trouble (although the downloadable content has always worked the same as ever). Well, those pages have all gotten an overhaul, and are working great now. You can play each word individually on the site, and view the words as simplified characters, traditional characters, or pinyin only.

Give them a try! They’re free, so you have nothing to lose, and much better pronunciation to gain.

14

Apr 2020The Door Door

Well, this one’s a little on the nose:

The character there is 門 (mén), a traditional character. It is written 门 in simplified Chinese. It means “door” or “gate.”

I’m curious what the story is behind this door. And why no 窗 (chuāng) windows??

09

Apr 2020April COVID-19 Updates (Shanghai)

I wrote that post a while back giving a fairly comprehensive account of “Coronavirus Lockdown in Shanghai.” It’s now almost a month later. So what’s different? Only little things.

Here’s a brief rundown:

- Almost everyone is still wearing masks when they go outside, but no one freaks out if I don’t. I wear my mask when required, or when in an elevator or other enclosed space. I do it more out of courtesy than anything else.

- The mall near my home stopped doing temperature checks about two weeks ago (but most still do).

- Where it’s still in place, “hygiene security” is getting laxer. It’s the little things… For example, we’re supposed to sign in every morning on the first floor of my office building, and yet no one says anything if you blow it off. We’re only supposed to go in through one entrance in my compound (where they’re still doing temperature checks), but the “nice guard” will let me in the side gate when he’s on duty. Visitors are allowed, and when my wife had two friends over last night, they said their temperates were not even checked at the gate.

- We’ve been hearing this since at least early March, but it looks like school will almost certainly resume in early May. (It’s still uncertain how the missed school is going to be made up… If I were a betting man, I’d put my money on no summer vacation this year.)

- My wife is back to full-time in her office.

- The big barber shops chains opened in early April, but a lot of restaurants are still closed. I’m sure many of them are “still closed” because they’re never going to reopen, but it can be hard to tell which those are. You do see a lot of shops getting renovated now, as the new tenant prepares to open a new store as the pandemic fades into the background.

- Over the weekend, I took my son to the Shanghai Natural History museum. (It’s pretty great; I recommend it!) It wasn’t super crowded, but there were quite a few people there (all wearing masks).

- This past Monday was a holiday, and my family and I went to Chenshan Botanical Garden to see the last of the cherry blossoms, and again: it wasn’t super crowded, but there were quite a few people there (all wearing masks).

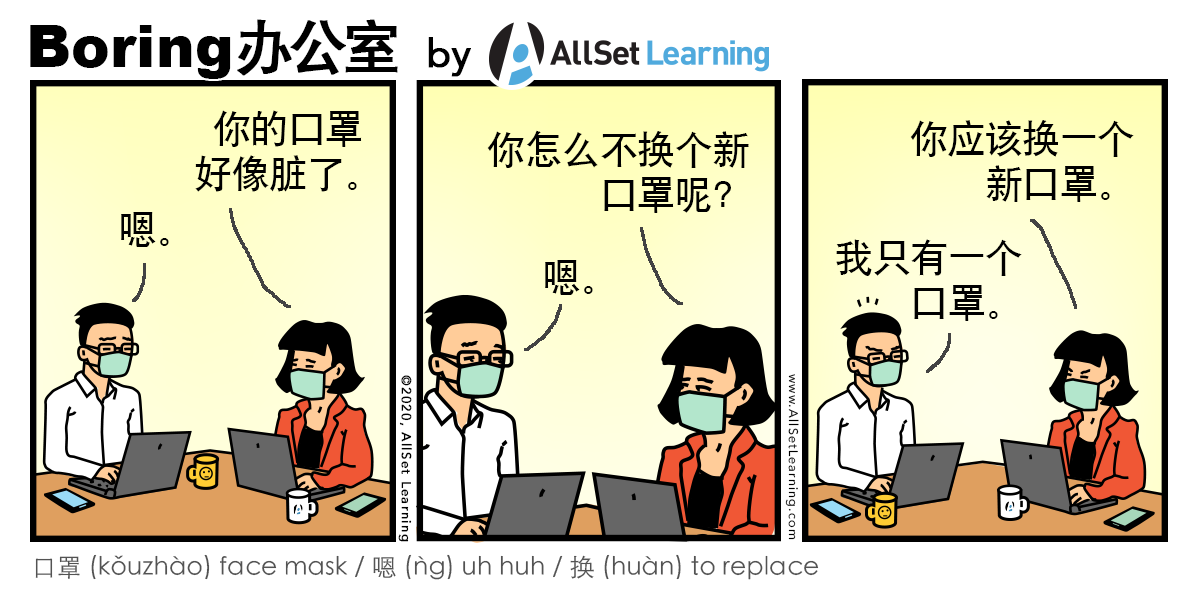

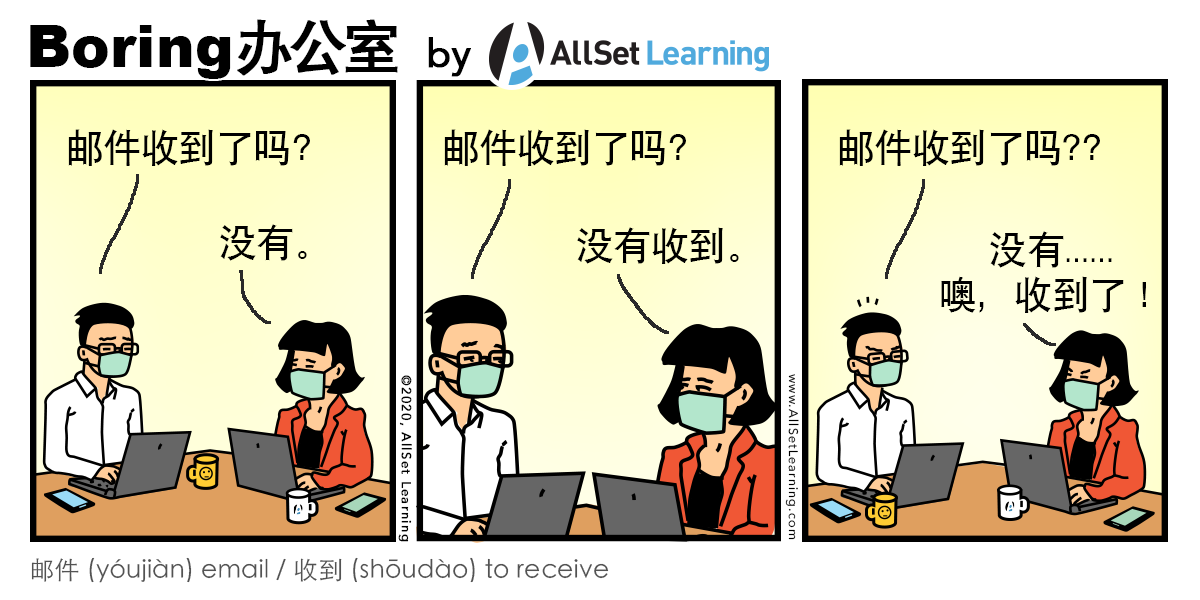

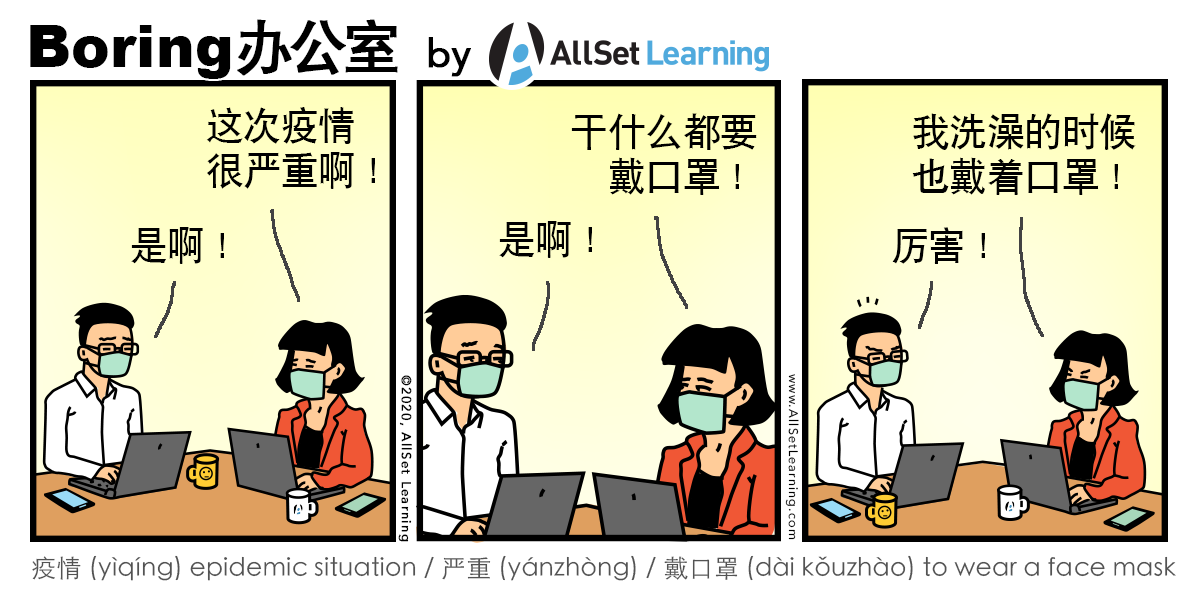

- Our new webcomic Boring 办公室 (Bàngōngshì) continues (there are 11 episodes as of today), and the characters will keep wearing the face masks for now, to reflect the current situation in Shanghai.

- Church services are still canceled, so no church-going for Easter.

Finally, on a lighter note, a few observations from someone who has almost made it through the COVID-19 pandemic in Shanghai…

The three most annoying things about wearing face masks all the time:

- I keep forgetting my face mask when I go out! Seriously, multiple times a day.

- Chewing gum with a face mask does not work. The mask slowly migrates downward. The effect is more pronounced if you haven’t shaved for a few days.

- The iPhone’s facial recognition doesn’t work when you have a mask on. Very annoying when you are 100% used to using it all day long, both to unlock your phone and make mobile payments.

Stay safe, everyone. There is a light at the end of this tunnel!

01

Apr 2020Challenges to Character Understanding

I recently read this post on Hacking Chinese: 5 levels of understanding Chinese characters: Superficial forms to deep structure and it really struck a chord with me. It reminds me a little of my own “5 Stages To Learning Chinese,” but it highlights some really great issues related to character learning which I’d like to dig into.

I’ll first do a quick summary of the author Olle’s 5 stages, but in my own words:

- Chineseasy Mode: Fully arbitrary character-image associations

- Lazy Heisig Mode: Systematic arbitrary character-image associations

- Diligent Heisig Mode: Systematic character-image associations, with substitutions

- OCD Heisig Mode: Systematic complete character-image associations

- Scholar Mode: Straight-up character origin research

Apologies to Olle, in that I may be misrepresenting his 5 stages a little bit in order to make a few points, but I believe that our groupings are mostly similar, and in any case, I am piggybacking on his article.

Chineasy Mode

This is not a compliment. I’m not a fan of Shao Lan’s Chineasy, at least not for any serious student of Chinese. Chineasy is fine as a fun “Chinese Characters Lite” if you have no intention of becoming literate in Chinese. (See also Dr. Victor Mair’s thoughts on it.)

The problem with it is that it’s not a system. It’s just Chinese character dress-up. You can’t memorize thousands of Chinese characters without a system. It’s how the Chinese themselves do it, and it’s how learners need to do it.

The question, then, becomes: how complicated of a system does this need to be?

Lazy Heisig Mode

I’ve written a little bit before about James Heisig and his books Remembering the Kanji (for Chinese characters in Japanese) and Remembering the Hanzi (for Chinese characters in Chinese).

Heisig’s work was an absolute breakthrough in the 1980’s. It was a breath of fresh air at a time when no one seemed to understand that practical language learning and scholarly language study of Asian languages did not have to be the same thing.

Heisig had the gall to “blasphemously” suggest that some systematically recurring character components could be assigned arbitrary meanings that the learner made up himself in order to concoct little mnemonic stories help him remember the correct meanings of the full characters.

If the “arbitrary” part is applied in moderation, this is definitely an improvement over the previous level, becomes you’re bringing a system into it. You’re recognizing that many character components are clear and easy to remember, plus they repeat a lot across different characters, and there’s a good reason for it. For the ones that aren’t clear or easy to be remember, you have a plan B. It’s a pragmatic system.

The problem here is that not every component has an obvious meaning, and if you start assigning many of your own un-scholarly meanings when you only know 50 characters, you’re not going to fully realize until you get to 500 characters that you really shouldn’t have chosen that meaning for that particular character component. But to change it now means changing a bunch of stories you had memorized. Yeah… it can be messy.

Diligent Heisig Mode

So if you were “lazy” before because you didn’t care what most components actually mean (historically), you’re “diligent” now in that you at least try to match the character components you are learning systematically to some kind of historical meaning.

You’re also actually paying attention to the difference between semantic (meaning) components and phonetic (sound) components. The extra time and effort spent here will really pay off when you make it to the advanced levels of your Chinese studies.

Keep in mind, however, that sometimes the “historically accurate” character breakdowns are simply not helpful or not practical (see “Scholar-Only Examples” below). In cases like these, even the “diligent” student may need to make a call in favor of his own sanity. He may need to “make something up” from time to time, but he tries not to. (In any case, the characters he punts on are likely the same ones literate native speakers have no clue about either.)

OCD Heisig Mode

But what if having a rough idea of semantic and phonetic component roles is not enough? What if you have to know the role of every character component for every character?

Well, I’d say that you may be a bit OCD… Or maybe that’s just your personal interest.

In either case, you’re probably spending far more time on your system than you need to. (What’s more important: your system, or reading Chinese?)

I won’t say too much about this.

Scholar Mode

Some learners really want to know the ins and outs of every character. And that’s cool. Clearly they have an interest that goes beyond the average learner’s.

But is this how far a learner needs to go? No. Recommending other learners go this route reminds me of a conversation I had with my 9th grade algebra teacher:

Me: Can we use a sheet of formulas for the test?

Teacher: No.

Me: *crestfallen* So we have to memorize them all.

Teacher: Well, I didn’t say that…

Me: *hope in my eyes* What do you mean?

Teacher: Well, if you understand the principles behind the formulas, you don’t need to memorize them when you can simply derive them yourself whenever you forget them…

Me: *hopes shattered*

These two people are not living in the same world.

Assessing the 5

Like Olle, I’d put myself in group 3, and it’s what I recommend that most clients do. As an elementary learner I was once in “Lazy Heisig Mode,” but I eventually realized my “system” was a bit of a mess, and I did the extra work to get to “Diligent Heisig Mode.” It’s a good place to be.

I’d say the 5 levels apply to most people like this:

- Chineasy Mode: Tourists only! You’re not a serious learner, and that’s OK.

- Lazy Heisig Mode: You’re not fully committed, and that’s OK too. If you decide to “go all the way” with Chinese, you can still upgrade later.

- Diligent Heisig Mode: You’re committed, and you don’t want to waste time forgetting and relearning. You’re building a strong foundation for the long road ahead.

- OCD Heisig Mode: I’m not sure you really exist? But anyway, if you do… you do you.

- Scholar Mode: The world needs scholars! Thank you for your hard work. (Just remember that not everyone aspires to be at your level.)

Scholar-Only Examples

You may not understand why it’s difficult and messy to learn the correct origins of all the characters you learn. I felt the same way once. I was all, “hey, I like language. I can handle it.”

OK, fair enough. I have some examples for you. No, you will not see the characters 山 or 月 or 好 or 明 or even 上 and 下. Those are the ones used to prove the opposing argument. Let’s look at a very simple beginner-level sentence.

你是我的朋友。 (Nǐ shì wǒ de péngyou.)

This is a first-semester Chinese sentence which means “You are my friend.” Easy vocabulary, easy grammar. Now let’s look at the characters.

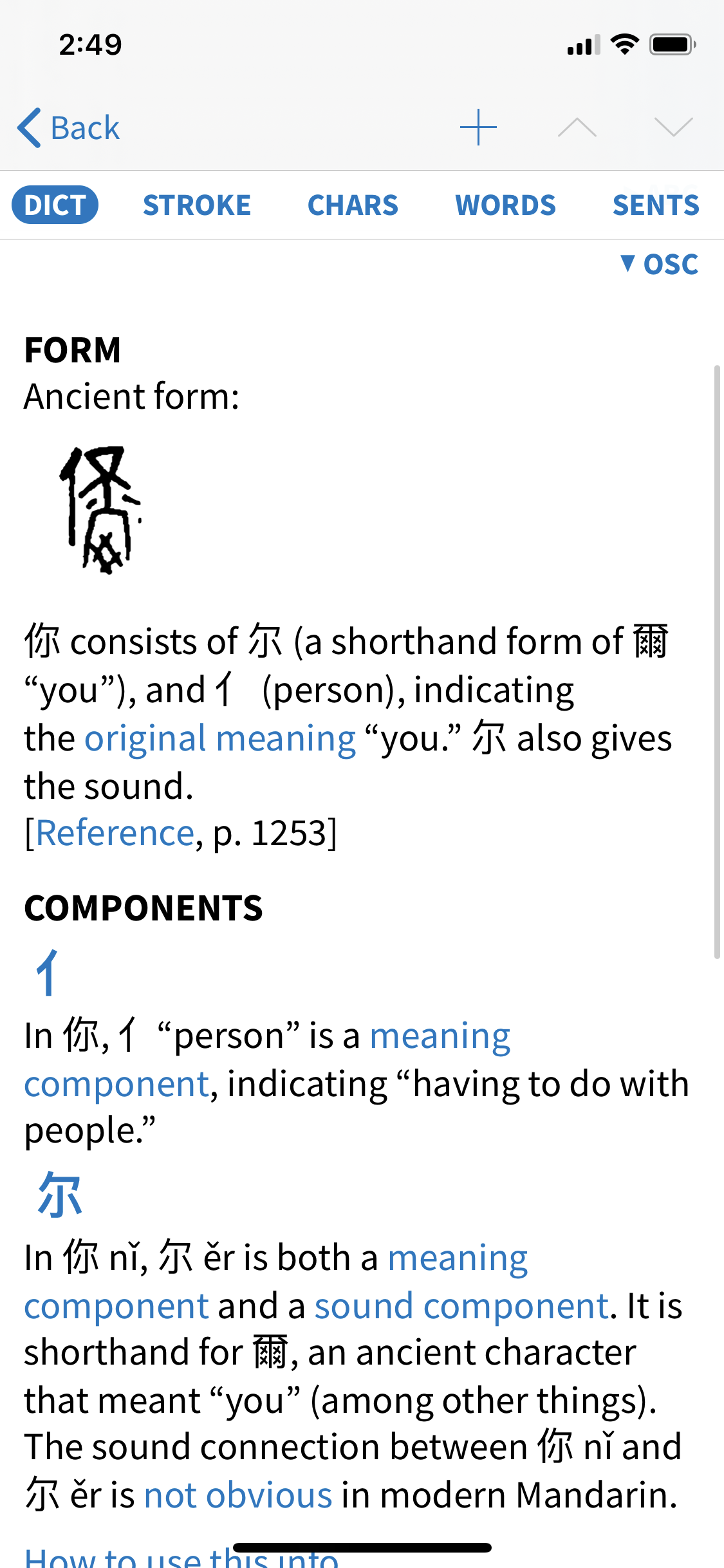

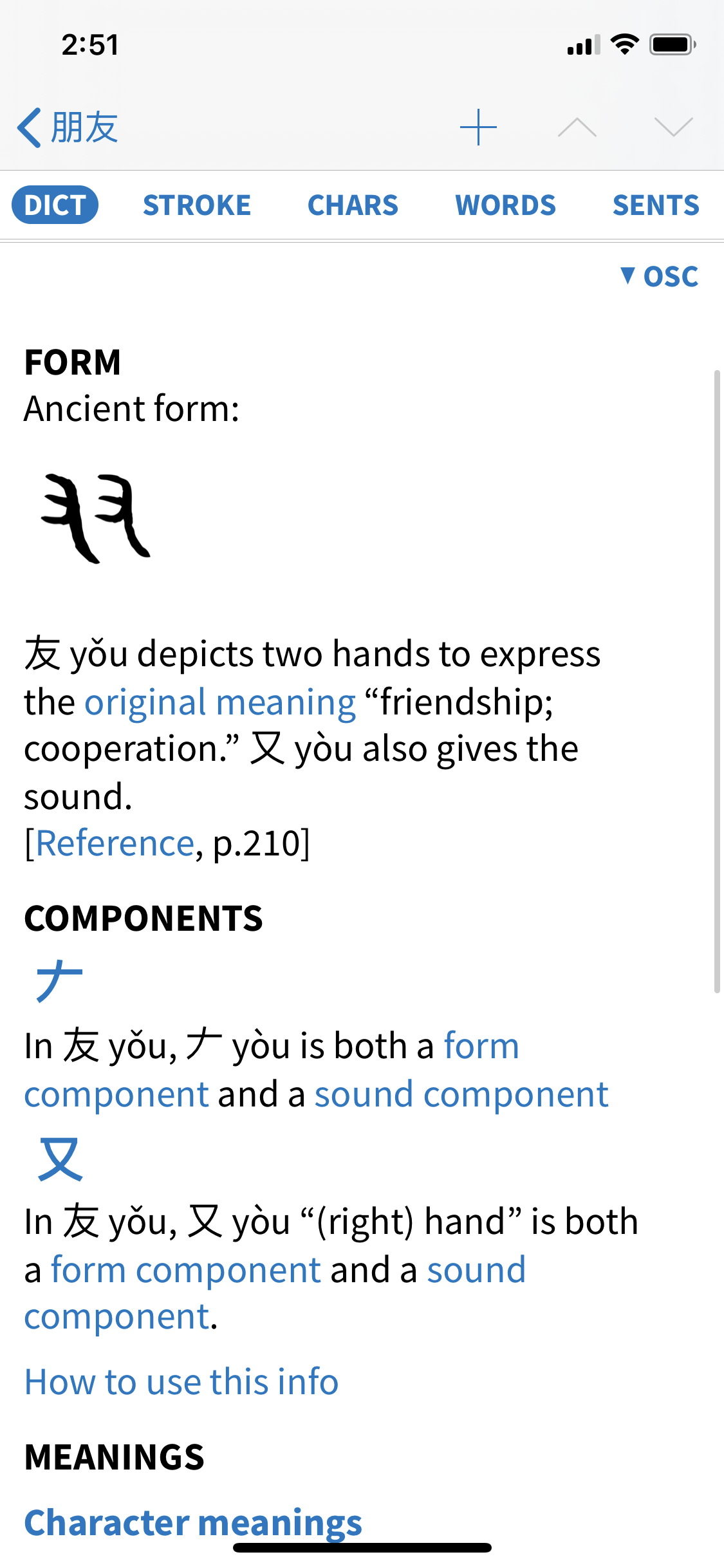

If you’re a serious student of Chinese, you probably know about the Outliers Chinese Dictionary for Pleco. Here are the entries for those characters:

你 (nǐ):

是 (shì):

我 (wǒ):

的 (de):

Not in my Outliers Dictionary. This explanation is from Wenlin:

In ancient times 的 meant ‘white’. Therefore 白 bái ‘white’ is a component in 的 (white: bright: clear: precise: bull’s-eye). 勺 sháo (‘spoon’) is phonetic: ancient 勺 *tsiak (modern sháo) sounded like ancient 的 *tiek (modern dì).

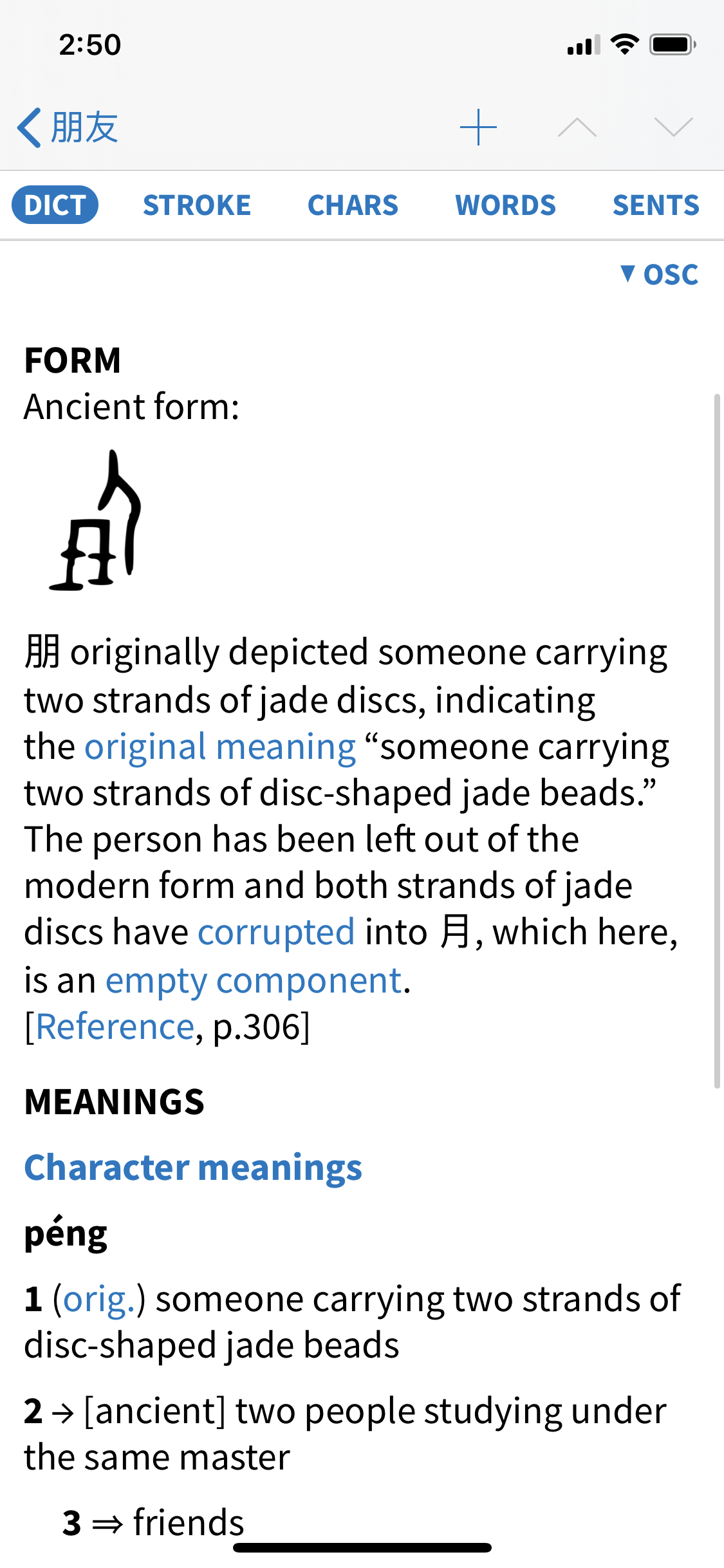

朋 (péng):

友 (you):

Holy crap. Don’t try to tell me that’s not a nightmare. It might be OK, if these were some cherry-picked exceptions, but they’re not, really. There are quite a few more common characters like this, although most characters are easier to make sense of when you break them down.

Try looking up the characters in this simple sentence if you want more trouble: 你不要说话! (Nǐ bùyào shuōhuà!)

Conclusions

The unfortunate truth is that many super-common characters have historical origins that are elusive to beginners, to put it nicely.

This is not the end of the world, though! If you’re in “Diligent Heisig Mode,” this is how you approach the “你是我的朋友” sentence above:

- 你: OK, the “person” radical is meaningful. That’s something! I’ll just have to deal with the right side somehow, since the character origin is useless to me.

- 是: All right, we have a “sun” (which I know!) and another component. This is a challenge, but it’s such a super-common word, that I can accept brute-forcing it into my memory somehow.

- 我: Yikes, a similar situation to 是, but with a much crazier form. Fortunately, there are not many of these.

- 的: Two clear components, and this is the #1 most common character in the whole language. So yeah… my memory can make an allowance for this one.

- 朋: OK, now we’re getting somewhere. A doubled-up component meaning “friend.” I can work with that.

- 友: Recognizable components. OK.

It gets easier, but there are a few speed bumps in the beginning. It’s for this reason that it can be very useful to not force yourself down that etymology rabbit hole for every new character you learn.

Most characters are composed of a sound component and a meaning component (they are called phono-semantic compounds), but the examples above are not so helpful in that way (even if some of them technically have a sound component). In any case, in order to “break into” the system and get it working for you, you have to do the work to learn the character component parts. Then the magic can start.

In conclusion: learn your character components (but not necessarily their full origins), and stay diligent. Your future Chinese literate self will thank you.

P.S. All my clients at AllSet Learning are strongly encouraged to become literate in Chinese using an approach similar to what I’ve discussed above. Feel free to get in touch.

P.P.S. I also discussed the Heisig method with my co-host Jared in our podcast, You Can Learn Chinese.

24

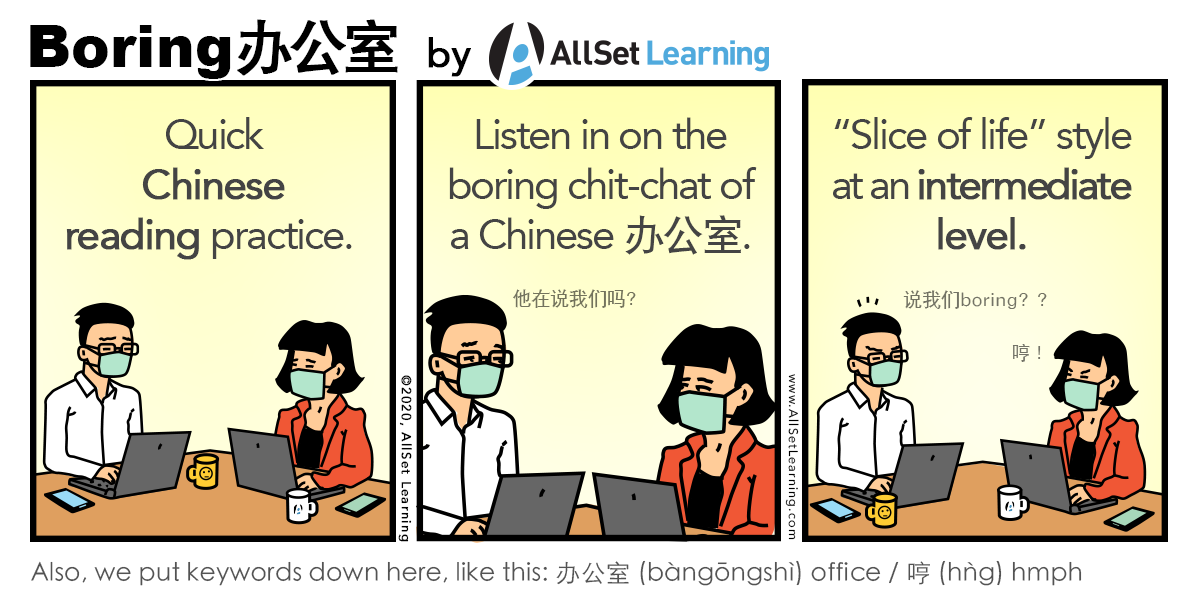

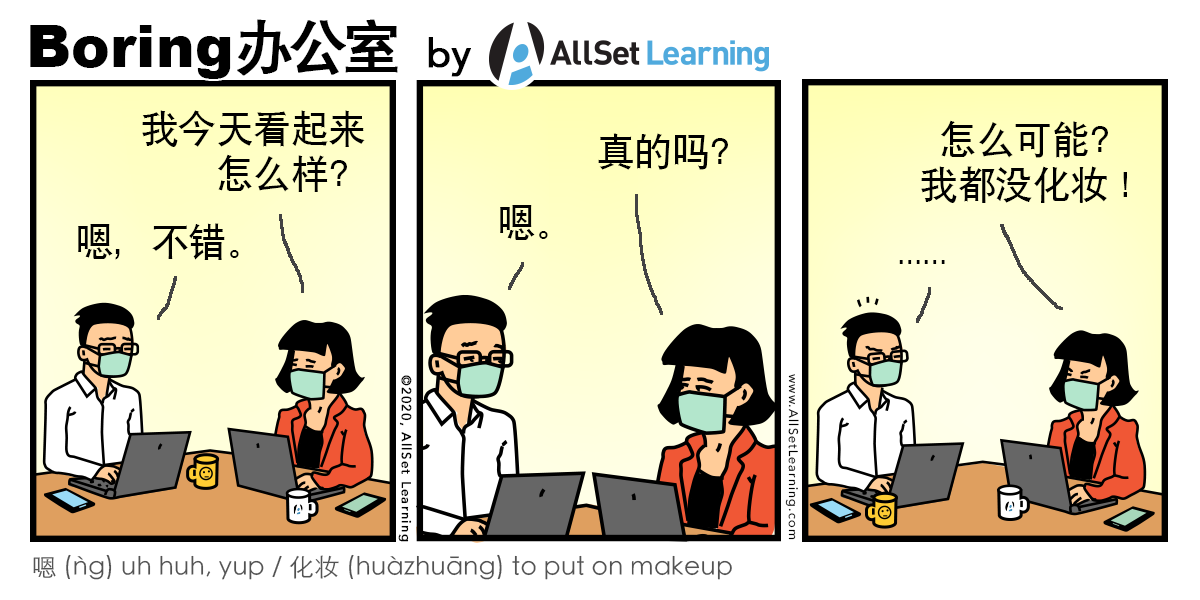

Mar 2020Boring Bangongshi: the Chinese Office Comic for Learners

So the team here at AllSet Learning has created a new thing! It’s an office-centric comic strip giving learners little bite-sized chunks of office language, and it’s called Boring 办公室 (Bàngōngshì). It was not originally intended to be COVID-19-focused, but it kind of turned out that way (for now).

Here’s the intro:

And here’s a taste of the comics:

You can click through each comic to get the full text of the dialog, grammar links, editor commentary, etc.

We just launched it, and there are plenty more comics in the pipeline.

So, please: share, discuss, criticize! If you read it, don’t find it funny, but keep reading, that is a win! We’re just trying to create material that learners don’t mind reading, at a level slightly higher than what’s more widely available (but still not too high).

Boring 办公室 (Bàngōngshì).

19

Mar 2020In Money We Trust

Pretty sure this is unironic?

The name of the shop is 钱店, literally “Money Shop.” This is one of those cases where traditional characters (錢店) are used in mainland China for stylistic effect.

This is a clothing and accessories shop near Zhongshan Park in Shanghai.

17

Mar 2020Unwarranted N-Word: Crimes of Song Lyric Translation into Chinese

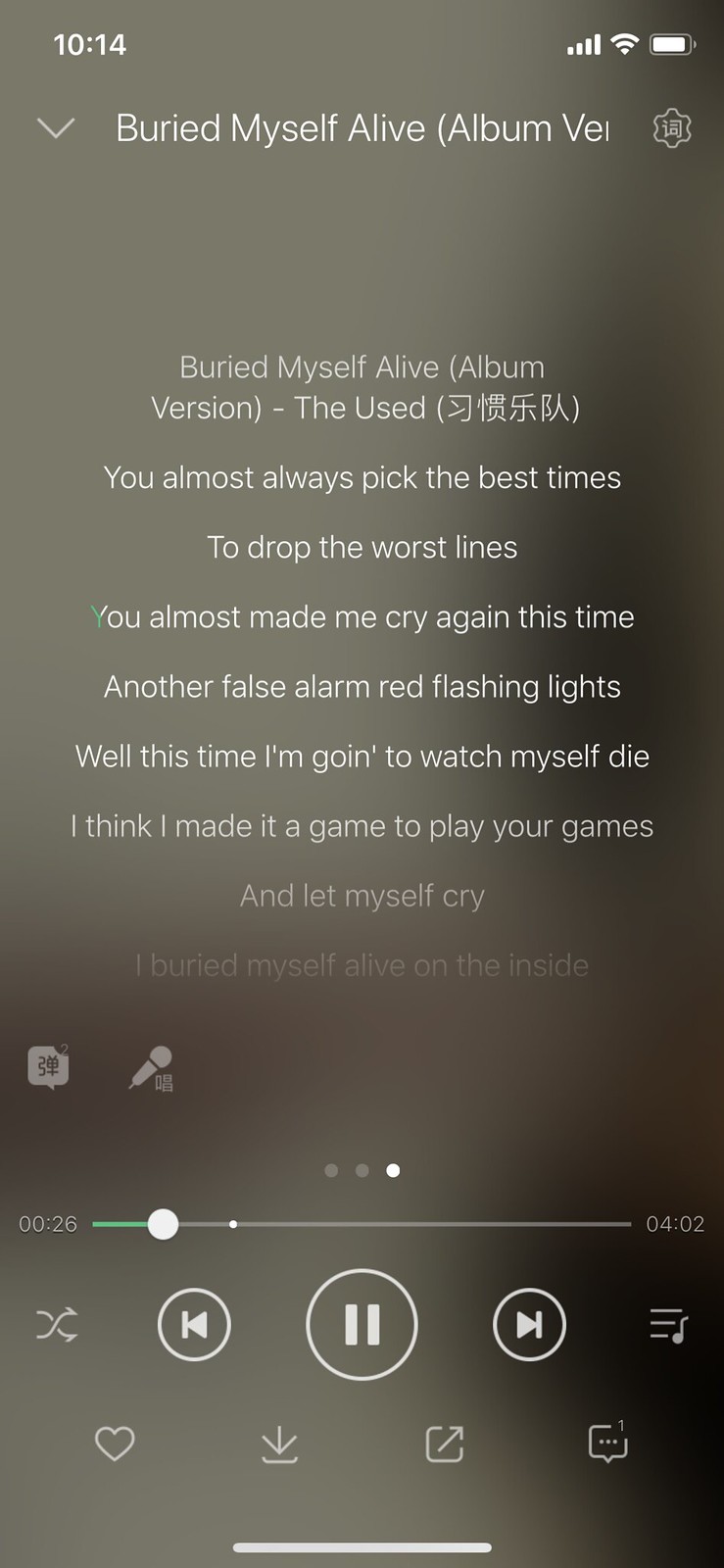

I’ve been using QQ Music for years already. It’s one tenth of the cost of Spotify, and it has almost all of the songs I want to listen to (plus no VPN required!). It has English lyrics for most of its songs, and sometimes even Chinese translations of those English lyrics.

I’m quite the reader of song lyrics, and sometimes QQ Music lets me down in weird ways. The first way is just bad translation. Song lyrics are a translation challenge no matter what, and I’m forgiving, but sometimes the translations into Chinese are just plain bad.

The Used

Do you remember that emo band called The Used? Here’s a YouTube video to refresh your memory:

Anyway, what do you think this band’s Chinese name is? Translated literally, it would be something ridiculous like 被利用着. Nope. This is it:

习惯乐队. 习惯 as in “customs” or “habits,” and 乐队 as in “band.” The word 习惯 also means “to get used to” (doing something), so some translator got the words right, but badly misunderstood the meaning of the band’s name. I guess he was thinking the band’s name meant something like “Getting Used to It”?? No idea.

This kind of translation mistake is fairly common on QQ Music, but not common enough that it bothers me too much.

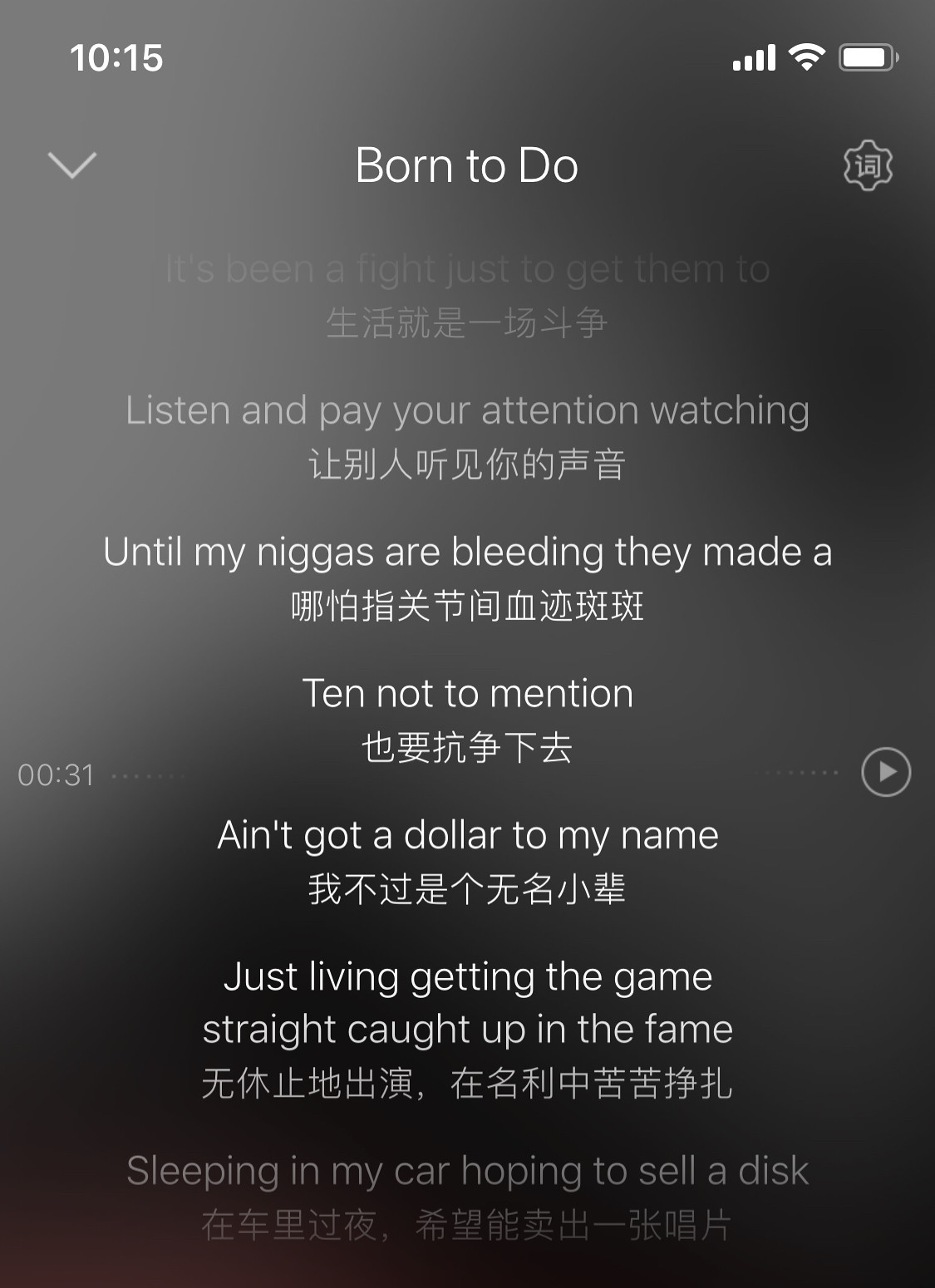

Perplexing Use of the N-Word

This next mistake, concerning Steven Cooper’s song “Born to Do,” really had me confused, though:

I randomly came across this song on QQ Music, and my kids liked it. I did a quick lyrics scan, and didn’t notice any bad words, so we listened to it. It wasn’t until after listening to this song several times that I read the lyrics carefully and discovered the N-word.

I was pretty shocked, because this is a Christian rapper. WHY did he feel the need to use that word (just once) in this song?? It didn’t make any sense.

The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that the lyric itself didn’t make any sense, and not just because of a bad transcription:

Locked in this room off through the night

Trying write

Every second of my life in this mic

It’s been a fight just to get them to

Listen and pay your attention watching

Until my n****s are bleeding

Wait, what? Who’s bleeding and why? It’s a song about how hard he tries to improve his skills at rapping because it’s what he was “born to do.” This particular part of the song is about writing.

So yes, the “n-word” here should have been “knuckles.”

How could such an offensive mistake happen? I’m sure a Christian rapper with clean lyrics takes care not to drop gratuitous N-bombs in his song lyrics.

The best I can guess is that the lyrics are transcribed by machine, not be a person. It’s kind of weird that a computer would identify the N-word. I mean, you can’t have it popping up randomly in Celine Dion songs or Disney lyrics, right? But maybe if a song is classified as rap, then the “ban use of the N-word” toggle is switched off.

Here’s how that section should have gone:

Locked in this room all through the night

Trying to write

Every second of my life in this mic

It’s been a fight just to get them to

Listen and pay attention watching

Until my knuckles are bleeding

There’s one final strange thing happening here, though… Although the English lyrics contain the N-word, the Chinese lyrics contain a translation of the word for “knuckles”: 指关节.

…and now I am totally at a loss to explain this!