23

Feb 2007Chinese Food for Laowai

Laowai Chinese recently hit on a topic I’ve been meaning to write about for a while: What Foreigners Like to Eat in China. It’s true that foreigners in China find many menu items to be a hassle (read: almost any fish), while others are just not usually pleasing to our palates (read: chicken feet). In his post Albert makes a very good list, although mine would be slightly different.

First, I’d list the essentials (excluding rice) for foreigners in China. These are the best dishes for someone who has just arrived, but they also tend to remain in the favorite lists of foreigners that have been here a while.

Essential Chinese Food

1. 宫保鸡丁 – Kung pow chicken. This has got to be the favorite. I still love it.

2. 饺子 – Dumplings. They come in boilded and fried varieties, but they’re all good.

3. 扬州炒饭 Yangzhou fried rice. It’s better than just plain fried rice, because it has ham (oops, I mean “ham”), shrimp, peas, etc. in it.

4. 鱼香肉丝 – Fishilicious Pork Strips. [OK, that’s not the official translation, but that’s the one I’ve been using since my Hangzhou days.] There’s no fish in it; it’s strips of pork and other good stuff in a sweetish, spicyish sauce. Foreigners usually love it with rice.

5. 羊肉串 – Lamb kebabs. This needs no explanation.

6. 番茄炒蛋 – Stir-fried eggs and tomato.

There are obviously a lot of other that could be listed (see Albert’s list), but those would be my essential six. I still enjoy all of them, despite favoring them heavily for over six years.

So basically, if a foreigner showed up in China alone, and was allowed to choose what food he wanted to eat without any outside influence, there’s a good chance he’d end up eating these six and liking them the best.

I feel like there should be ten, though. Ten is a much nicer number. I wish I had time to make a list of the “perfect ten,” but I have a plane to catch to Chongqing.

Bon appétit!

21

Feb 2007A Day in Chongqing

My wife is going to Chongqing on business, and she’ll be free the whole day on Friday, February 23rd. She was able to get me a ticket to accompany her, so that means we have one day to check out what Chongqing has to offer. It’s probably not the best time of year to go, but oh well. (And yes, we both like spicy food!)

I chucked my Lonely Planet long ago, but in looking for info on Chongqing, I was thinking that there should be an online version of Lonely Planet. Something less commercial, in wiki format, that could offer the most up-to-date info on hot travel spots. That’s when I found WikiTravel.org. The site’s a little… visually boring, but it seems very functional. It has a page on Chongqing, but it doesn’t seem to offer much. Are the Dazu Rock Carvings (大足石刻) worth checking out?

To anyone who has been to Chongqing or lives in Chongqing, I would love to hear some suggestions of fun or interesting things to do. Thanks in advance!

19

Feb 2007Best Chinese New Year Podcast for Learning Chinese

I may “hate” Chinese New Year, but it’s inescapable. We also do coverage of it at ChinesePod, of course. This year we did an Elementary lesson on Chinese New Year Firecrackers, but the one I especially liked was at the Advanced level, called 春节采访 (“Chinese New Year Interview”).

I’ve talked about the Advanced lessons on ChinesePod before, and one of the criticisms I got was that the dialogues (which are scripted) seem too fake. I think that’s a valid criticism, and I totally agree with it. The 春节采访 podcast was partly an experiment to see what we could do when we went “totally natural.” Here’s how we did it:

1. The academic team brainstormed questions about the topic (in this case, Chinese New Year), then chose the six most interesting ones

2. We made a list of all the Chinese employees in the office and where they’re from so that we could have a variety of accents in the podcast, then chose 6-8 to interview (being sure to include both male and female)

3. After Xiao Xia interviewed everyone, we narrowed the results down to (1) the most interesting interviewees, and then (2) the most interesting answers, making sure that we kept a balance in both accents and genders

4. The audio production team cut out everything we didn’t need/want

5. The academic team transcribed the final interview audio

6. Jenny and Xiao Xia listened to the audio and used the transcript to go over the interview material for the full podcast

I think the result was a very interesting Chinese New Year podcast. Most of the language wasn’t difficult at all, but there are a few challenging parts that go into lesser known local customs. The “dialogue” part of the podcast was a lot longer than usual, but I’m sure this won’t bother the listeners. As a result of that, though, the transcript was significantly longer than usual.

I think this dialogue was definitely a step in the right direction for a better advanced podcast. The problem is that it takes much longer to create natural content like this; it would be impossible to do it for every podcast. You have to expect to get boring and/or unusable content, so you have to record a lot more and cut out what you don’t want. So that’s a lot of extra time editing, and then transcribing as well. Still, I think there are elements of this process that we can keep using going forward to produce more engaging content.

If any learners have any thoughts on this, I’d be happy to hear them. You probably want to listen to the podcast first (remember that it’s all in Chinese). If you haven’t listened to ChinesePod’s Advanced content lately, you definitely need to check it out.

17

Feb 200710 Reasons I Hate Chinese New Year

I am well known for being positive and upbeat about life in China, but sometimes I just have to vent a little. This one is a special case, because when I first arrived in China I was thrilled to be celebrating the real Chinese New Year, with real Chinese people, the authentic way. With each passing year my enthusiasm has faded just a bit more, until it became this colorless loathing for the alpha holiday of the Chinese calendar.

I suppose “hate” is a strong word, but let me just say I’m not fond of the ol’ CNY. (Still, I’m keeping the word “hate” because I’m so sassy.) So now I give you the 10 reasons I hate Chinese New Year, in the order that they come to me:

1. It’s noisy. Yeah, fireworks are fun. Yeah, the Chinese invented them. Yippee. I always thought the best fireworks were the bottle rockets that exploded midair in colorful displays. Well, here in China, the most common kind is firecrackers, or just any kind that isn’t much to look at but makes a lot of noise. This kind is fun in moderation, but “moderation” is entirely out of the question when CNY rolls around. We’re talking non-stop pili-pala (the sound of firecrackers) for days on end. What? You wanted to go to sleep? Too bad. What? You wanted to sleep in past 6am on your vacation? Too bad.

2. It’s dangerous. It should come as no surprise that an environment seething with explosions is not particularly safe. The Chinese aren’t exactly world-renowned for being “safety conscious,” either. If the public pyrotechnics everywhere weren’t bad enough, this is also the time of year when kids have firecrackers too, and they just go around lighting and throwing them at random.

3. It paralyzes the nation. Not being able to get a taxi or go to your favorite restaurant isn’t the end of the world (although, my regular Xinjiang restaurant, I do not forgive you for going back to Xinjiang for CNY an entire month early — I’m pretty sure you didn’t walk back). The problem comes when you try to do anything bureaucratic. Virtually nothing can be accomplished if CNY is even remotely near. It’s all a smile and a mei banfa (there’s nothing we can do). It’s an excuse that’s not only incontrovertible, but one you’re also supposed to be happy about it. You had better hope your visa doesn’t expire right before Chinese New Year, because you’d be screwed.

4. It encourages craptaculars. The Chinese New Year craptacular (春节联欢晚会) is the mother of all Chinese craptaculars. Watching it is not only a family tradition for many, many Chinese families; it almost seems like a patriotic duty. Year after year, I hear people saying, “the craptacular was crappier than ever this year,” and yet they watch it, year after year after year. This horrible TV tradition somehow imbedded itself in the nation’s cultural DNA, and the populace seems resigned to this.

5. It brings out overzealous hospitality. Chinese food is good. Eating is good. But Chinese hosts are infamous for “hospitably” force-feeding their guests, and this is the holiday when that impulse goes into overdrive. You can starve yourself for days, but it will do no good. As the old Chinese proverb goes, “even a large bucket cannot hold the sea.” (OK, I made that up, but it sure makes my point.)

6. It involves lots of Chinese liquor. I like Chinese food, but I will never like Chinese rice wine. This is one of those Chinese holidays where I have to buck up and just drink it. I’d be a dick if I refused. And man, it is nasty.

7. It causes temporal cognitive chaos. I’ve talked about this before. Around CNY, Chinese people refuse to use the solar calendar for a week or two and cognitively switch over to that alternative universe where the moon determines the dates. If you don’t make the temporary crossover with them, you’re in for some serious calendar confusion.

8. It screws over the little guy. At Chinese New Year, everyone goes home to spend the holiday with their families. Oh wait, did I say “everyone”? I meant everyone except for the wage slaves that have to work in the restaurants for the New Year’s Eve dinner because the city folk don’t like to bother celebrating at home anymore. Oh, and except for drivers and operators of essential public transportation. The more commercialized the holiday becomes, the more people that get cheated out of it. This is nothing new to someone from a capitalist nation, but it doesn’t mean I have to like it when I see it happening anywhere.

9. It’s a mass migration the country can’t really handle. It really can’t. One of my co-workers from Guilin will not be spending the holiday with her family for the first time ever because she simply could not get a ticket home. She’s not the only one. It’s just way too many people trying to “go home” all at the same time. It’s the world’s largest human migration, and it’s only getting worse as more and more people move to the big cities to make a living. It’s one hell of a problem for the government, totally cultural in origin.

10. It’s serious pollution. Those fireworks are more than just noisy and dangerous; they’re bad for the environment. Keep in mind that in China there are way more people more densely packed than in the U.S.; the amount of fireworks going off in one night all across the nation is simply staggering. If China didn’t already have such a great handle on its environmental issues, I might be worried. (Oh, wait a minute…)

I have tried for years to warm up to Chinese New Year, but I have stopped trying. My conclusion is that if you didn’t experience Chinese New Year as a child, you’re not going to learn to like it. It’s an exciting holiday for a Chinese kid… you get to see all those fun cousins, eat lots of great food in ridiculous quantities, and receive a hongbao (red envelope full of cash) from all your relatives. As an adult cultural outsider, I really don’t think I have any hope of ever truly enjoying this holiday.

But, here we go again…

16

Feb 2007Pulp Fiction Apartment Hunting

There was a great entry at Jottings from the Granite Studio this week which combines Pulp Fiction lines with the very frustrating experience of trying to find a decent apartment in Beijing. Here’s a quick sample.

> Bring out the Gimp.

> The landlord was sweet as pie. She was wonderful. Her boyfriend was charming, all smiles, a real modern guy with “Starbucks” latte in hand. And then in walked “Auntie.” She was a dumpy, troll-like figure with a sour, peasant visage that betrayed no sense of warmth or mirth. It was quite a miracle when I saw her face actually begin to brighten into a grin when she met me… if only I knew.

Check out the whole entry: Pulp Fiction and Apartment hunting in Beijing. It’s great to see creative stuff like this, especially when it’s this funny.

14

Feb 2007Doomsday Family Gift Exchange

Over at ChinesePod we’ve all been amused lately at the comments left by Japanese learner “Changye.” He has taken to posting rather poetic musings. Here are his thoughts on our recent Valentine’s Day Gift lesson:

> Doomsday is just around the corner.

Now I am eating chocolate in front of my PC.

But I am sorry that it is “not” a Valentine’s Day gift.

I have no choice but to count on the family gift exchange.

Indeed.

13

Feb 2007Times Online Fumbles Pinyin

Reader Ash (of China Car Times) points out that Times Online is doing a “learn Mandarin Chinese” feature, complete with audio.

This is cool and all, but I found their online transcript a bit disturbing. A sample from Lesson 6:

> Part 1: Taking a train

> Clerk Qù nâr?

Leigh Qù Xî’ân.

Clerk Jî zhâng?

Leigh Liâng zhâng.

So, first and third tones don’t need to be distinguished, and pinyin conventions for how to write tone marks can be discarded at will?

I have a feeling someone made this call because there were pinyin encoding issues when proper tones were used. Still, this is pretty bad.

12

Feb 2007The Poor Man's Soft Bristle Toothbush

When you leave your comfy Western nation for a long stint in China, there are certain things you might want to take with you because you can’t buy them over there. I’m talking dental floss. Deodorant. Size 13+ shoes.

“Toothbrushes” used to be on my list. This is not because you can’t buy toothbrushes in China; you can buy one at any supermarket or convenience store, and you can even find brands you recognize, like Crest. The reason is that I find Chinese toothbrushes to have ridiculously stiff bristles. I guess I have wussy gums, but Chinese toothbrush bristles tend to fall in two categories for me: hard and gum-shredding. (Seriously, if I wanted that kind of scrubbing power in my toothbrush, I would use steel wool.)

So, I had been importing my soft bristle toothbrushes from the States in order to keep my brushing sessions pleasant. But now I know a better way.

Take a typical Chinese toothbrush. Pour a little bit of extremely hot water over the bristles. Apply toothpaste, and brush. The hot water softens the bristles just long enough for you to brush your teeth comfortably. Toothbrushes and big thermoses of boiling water are fairly ubiquitous in China, so the trick works basically anywhere.

Enjoy this technique, my tender-gummed friends, and may you not lose a single tooth in China.

11

Feb 2007性感的陕西话

最近我的老婆经常看《武林外传》,觉得很有趣。她还说女主角讲的陕西普通话很性感。我听得出有口音,但我听不出什么“性感”。这样的问题好像是native speaker语感的领域。

你们说,陕西话到底有什么性感呢?

10

Feb 2007How China Destroys Your English

I’ve been living in China a while now… long enough to observe the long-term deterioration of my own native language abilities, as well as those of my fellow English speakers. This deterioration can take different forms, one of which is a general decay of one’s vocabulary. Although it is a very real phenomenon (the other day I used “export” when I meant to use “deport,” which is really kind of pathetic), this kind of loss of mastery is due to lack of exposure, whether it be through media or human interaction with other native speakers. It would happen in any country, to speakers of any language, given that one’s native language is not being sufficiently exercised.

What I’d like to talk about is a much more insidious form of linguistic deterioration. Its source is, specifically, Chinese culture, and its target is English speakers. If you are a native speaker of English living in China, you may have already fallen victim. Below I give some of the common ways that the Chinese environment strikes down the native speaker’s linguistic competence.

1. Net bar. In Chinese, they’re called 网吧. This is fine. We generally call them “internet cafes” in English. The Chinese seem to think that 网吧 should be translated as “net bar” in English, and many unwary foreigners have even been beguiled by this idea. For English teachers, it’s usually one of the first nonstandard usage to creep in.

2. Name card. In the English-speaking world, business people have lots of business meetings to discuss business. On these occasions of business, said business people exchange specially printed pieces of paper known as business cards. In China everyone calls them “name cards,” ostensibly because in Chinese they are called 名片 and “name card” is a more direct translation. The use of “name card” is very widespread among foreigners living in China. In doing business with the Chinese, they seem to forget the word “business card” extremely quickly.

3. House. Most Chinese people live in apartments. They refer to these as their 家 (homes). When they purchase these apartments (OK, technically, they should be called “condos” at this point, but these Chinese domiciles doesn’t really conform to any image of “condo” I’ve ever had), they say they are buying a 房子. This word is frequently translated as “house,” but in practice it, too, is just another apartment/condo. Only the wealthy own what one could really call a “house,” and they are called 别墅 by the Chinese. Yet we foreigners in China still find ourselves referring to Chinese apartments as a “house.” I might refer to “your house” when I really mean “your apartment.” It’s totally not a house, and it’s honestly kind of embarrassing.

4. Bean curd. It’s called “tofu,” OK? This English word comes from Chinese (by way of Japanese). I know all dictionaries sold in China will tell you 豆腐 is “bean curd” in English, and that may represent the two characters nicely, but “bean curd” is more a definition than a comfortable translation. And yet some foreigners start saying “bean curd” rather than tofu. Deplorable.

I think you see the pattern. The normal native speaker way of saying something (internet cafe, business card, tofu, etc.) is replaced by a more awkward way of saying it using other English words — a way that conforms nicely to some Chinese word.

There have got to be more of these, but this short list is a good start. If you’ve been living in China a while and find yourself using all of these, you might be on dangerous ground. You’re going to start making a fool of yourself on trips home. Be vigilant! Resist China’s attempts at sabotaging your own command of your mother tongue!

(If you have any more of these, I’d love to hear them. It’s not quite of the same class, but I find myself occasionally saying “mai” instead of “buy” because the Chinese word for “buy” (买) sounds almost the same as “buy,” except for the initial consonant. The point of articulation is even the same.)

07

Feb 2007144 Days Outside the Law

I recently took a look at my passport and discovered that my student visa was expired. Long expired. It had expired on September 15th, 2006.

As you can imagine, I kind of freaked out a little at first. My wife is here. My home is here. My job is here. What if they bust in and drag me away, kicking and screaming, for my egregious visa overstay? Seemed plausible.

I was kinda pissed at East China Normal University. They handle my visa. They never even mentioned anything about visa renewal to me. I talked to them, and they claimed they had called me and/or e-mailed me about it (they did neither), and that if I really never heard from them, then maybe I somehow slipped through the cracks when they switched from the old system to the new networked system. I suspect me being one of the few foreign grad students played a factor as well. Anyway, all this was kind of irrelevant, because at the end of the day, I alone am responsible for making sure I have a valid visa. It’s right there in my passport. I may be busy, but I must watch that expiration date.

So how was it resolved? The school wrote a letter for me saying I was a great student and to please be lenient when fining me. They gave me the form with signature and seal that I needed for the new study visa. They also told me that I was facing a maximum fine of 5000 RMB. (That’s about US$644.)

05

Feb 2007How the Fruit Vendors Cheat You

A while back I noticed a cool food blog called LikeaLocal.cn when it went up on the China Blog List. I checked it out again recently, and it seems to have really taken off. It’s a great source for: (1) cheap food locations (in Shanghai), (2) cheap food order recommendations, (3) the Chinese needed to put in those orders (street food vendors don’t tend to be fluent in English).

I especially enjoyed an entry misleadingly titled Strawberries. I call it misleading because the bulk of the entry is about how the street vendors will try to cheat you and how you can get out of being cheated.

Here’s a great sample:

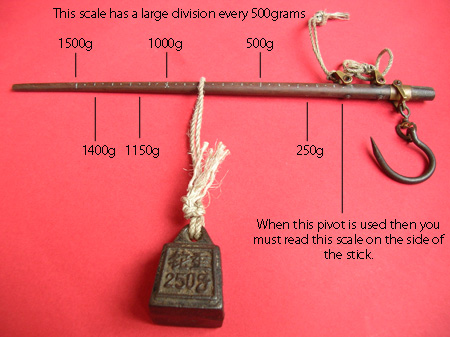

> Now you know how the scales work, but he will still cheat you! On the weight used to balance the stick in the photo it is written 250grams. Its actual weight is 225grams. The scale in the picture, and on most sticks I presume, is inaccurate (but always inaccurate in the seller’s favour). (BTW I bought my stick for 10rmb a pudong strawberry seller). The best way to prevent yourself being cheated on the weight is to make sure you have a 500ml water or fruit drink bottle (unopened) with you. Buy that in any convenience store. As you know, 500ml weighs 500grams. Now you can test his stick, scale, and weight by weighing your drink bottle. Cool huh?

Here’s a picture of that stick:

Get on over to Likealocal.cn. Good stuff.

04

Feb 2007一月份活动报告

一月份我连一次都没有写博克,所以我向大家汇报我一月份的活动:

1. 完成了应用语言学硕士课程的第三个学期

2. 离开租了两年的公寓,搬到了新家

3. 6号感冒了,整个一月份都没有好(都怪上海的臭气候)

4. 买了新的电脑,硬盘为320GB(终于可以拼命的下载BT咯!)

谢谢大家的耐心。二月份我会多写的。

02

Feb 2007Mental Ruts of a Financial Nature

Humans are such creatures of habit. Take, for example, the matter of salary. In the States it’s always a yearly figure. I have a good idea of how an American can live in $50k a year, or $75k a year, or $100k a year, etc. Likewise, salaries in China are always given per month. I have a good idea what it means to live in China on RMB 1k per month, RMB 5k per month, RMB 10k per month, etc. However, if an American asks me about Chinese yearly salaries, or a Chinese person asks me about American monthly salaries, I am thrown for a loop every time. I have to do the calculations. I don’t have a “sense” for it because I’m not in the habit of thinking about the figures that way. It’s really quite annoying.

Maybe I’m the only one that will ever use it, but I’ve made a little conversion table based on the current conversion rate of US$1 = RMB7.7743. (Numbers rounded to the nearest unit.)

| USD/year | RMB/year | USD/month | RMB/month |

| $1,544 | ¥12,000 | $129 | ¥1000 |

| $4,631 | ¥36,000 | $386 | ¥3000 |

| $7,718 | ¥60,000 | $643 | ¥5000 |

| $15,435 | ¥120,000 | $1,286 | ¥10,000 |

| $23,153 | ¥180,000 | $1,929 | ¥15,000 |

| $30,871 | ¥240,000 | $2,573 | ¥20,000 |

| $40,000 | ¥310,972 | $3,333 | ¥25,914 |

| $50,000 | ¥388,715 | $4,167 | ¥32,393 |

| $75,000 | ¥583,072 | $6,250 | ¥48,589 |

| $100,000 | ¥777,430 | $8,333 | ¥64,786 |

| $150,000 | ¥1,166,145 | $12,500 | ¥97,179 |

| $200,000 | ¥1,554,860 | $16,667 | ¥129,572 |

| $500,000 | ¥3,887,150 | $41,667 | ¥323,929 |

| $1,000,000 | ¥7,774,300 | $83,333 | ¥647,858 |

The chart also reveals a shortcut that the non-mathematicians among us may not have been aware of: if you increase the RMB monthly salary by 50%, you get very close to the annual dollar salary. Conversely, if you decrease the annual dollar salary by one third, you get close to the monthly RMB salary. (This would work more precisely if the conversion were still 8 RMB to the US dollar.) Anyway, this might be useful to some people. I should have noticed this long ago.

31

Jan 2007Boo and Reboo

Some definitions:

Boo

1. A sound uttered to show contempt, scorn, or disapproval. (source: Dictionary.com)

2. Boo is a term that is derived from the French word “beau” meaning beautiful. In 18th century England it meant an admirer, usually male. It made it’s way into Afro-Caribean language perhaps through the French colonisation of some Caribean islands. [Boo now means] girl or boyfriend. (source: UrbanDictionary.com)

Reboo

1. rumble (source: Dictionary.com)

2. Something that is cool, is reboo. Reboo is a word used mainly by people(s) who eat tacos, nachos and burritos. But you can use it as well. (source: UrbanDictionary.com)

3. The name of a cafeteria-style Chinese restaurant (source: the streets of Shanghai)

29

Jan 2007Flickr, YouTube, and Google Video Problems in China

For the past two days or so, none of the little button images on any Flickr pages will load. This is what I see above each image on the individual photo page:

The actual photos load fine. Fortunately most of the site navigation is text, but the little buttons above each image are image files, and none of them display. What’s worse is that there are no alt tags or tooltips for them, so I have to guess if I am to use any of them.

While I’m whining about sites not loading properly in China, I feel the need to mention that YouTube hasn’t loaded reliably for something like a month. The earthquake which affected all of China did a number on YouTube as well, but it seems like YouTube has been a lot less reliable ever since Google bought it. I suppose this shouldn’t be surprising, since you can’t even play Google videos in China (Google’s decision), but it sure is annoying.

“Don’t be evil” is a nice goal, but I’ll settle for “give China its free video” for the time being.

2006-01-31 Update: YouTube is finally working again! Flickr also seems back to normal.

28

Jan 2007WordPress Upgrade Today

My web host, DreamHost, offers a really great one-click install feature through its control panel. Using it, you can install the latest version of WordPress ridiculously easily. Even better, you can upgrade any WordPress install with a simple click… as long as that WordPress installation was installed using the one-click install system.

So here’s my problem. I have recognized the awesomeness of the one-click install/upgrade system, but if I want to take advantage of it, I have no choice but to export my entire blog — entries, comments, theme, plugins, modifications and all — and then re-import them all on a fresh one-click WordPress install. I’m doing this today. I think it will be worth it.

Anyway, if there’s any down time, you know why.

26

Jan 2007Stupid or Stay?

As academic director at ChinesePod, one of the things I deal with is the language questions of the users. Some of the questions are easy, and others are incredibly difficult. One of the types of questions I enjoy answering most are the ones that I had myself a few years back. Here is one such question (from this lesson):

> Just curious. Why does the transcript use the character 呆 dāi and not the character 待 dāi? Doesn’t the character 呆 dāi mean “stupid” and the character 待 dāi mean “stay”? Am I missing some fine distinction or something?

My answer:

> The character 待 (dāi) would seem to make a lot more sense, meaning “stay/reside in a place,” but 呆 (dāi) is actually the character used. If you look it up in a dictionary, you’ll see.

> And yes, 呆 (dāi) does also mean something like “stupid.” But that’s an adjective [technically, stative verb], and it’s a verb when it means “to stay.”

> Are you imagining the following exchange?

> Chinese Person: 你呆了多久了?

> You: 一年。

> Chinese Person: Hahaha!

> You: What?

> Chinese Person: You just admitted that you’ve been stupid for a year!

> You: No, wait! I thought you were using the “stay” meaning! Let me take it back!

> Chinese Person: No way, stupid!

> You: NOOOOooooo…

> Don’t worry, that doesn’t happen. 你呆了多久了? (Nǐ dāi le duōjiǔ le?) will always be interpreted as “how long have you stayed” rather than “how long have you been stupid.”

Anyone know why the character 呆 is used to mean “stay?”

24

Jan 2007Roujiamo Delivers!

Some of the best news I got all last week was that my favorite food in the Zhongshan Park area now delivers. It’s just this tiny stand, but they now bring this deliciousness right to your doorstep. I think it’s something like a 10 RMB minimum order. Sounds like a good excuse for a 肉夹馍 party to me.

If you don’t have the fortune of knowing what roujiamo is, check out these photos. If you detest the vile weed as much as I do, you’ll also want to make sure you know how to tell them to hold the cilantro.

OK, I have to admit: the main reason I took this photo was for the phone number. Now John B and Micah have it too. Anyone else in the Zhongshan Park area? You’re welcome.

21

Jan 2007ICBC’s Creative Character Writing

I’ve written about this before. I like creative ways of writing of Chinese characters. Here’s a simple one by 工商银行 (Industrial and Commercial Bank of China):

The characters read 融汇贯通, a kind of financial service the bank offers. The red part in 融 is the bank’s logo. The red part in 汇 looks similar to the bank’s logo, but actually more closely resembles half of an old-style Chinese coin, with the square hole in the middle. (The character 汇 refers to “currency.”)