19

Mar 2009Korean Update

I while back I announced I was studying Korean, and since then I’ve had quite a few inquiries as to how it’s going. So let me make an official update: it’s not going. Yeah, that whole Korean study didn’t last too long.

Why not? Well, it turns out my reasons for studying Korean weren’t very good in the first place. A quick recap of why I decided to study Korean:

1. Korean looks cool.

2. Korean writing is phonetic.

3. I’ve already got a good foundation in 2 of 3 major East Asian languages down (might as well go for the East Asian Linguistic Trilogy).

4. It’s easy to do in China.

Just in case these reasons don’t strike you as entirely stupid, I’ll add a few incisive questions into the mix:

1. Do you need to learn Korean? Not at all.

2. Do you have plans to go to Korea? No, not really. Been there once, and it was nice, but I’m not itching to go back.

3. Do you have a love of Korean culture? TV dramas, maybe? No, not really.

4. Do you have many Korean friends that you could practice with? No.

5. Is learning Korean related to any other long-term goals you might have? No, not at all.

Hmmm, OK, I think that’s probably enough. So I basically had no compelling reason to learn Korean, and I gave it a shot anyway. It lasted 2-3 months, I learned a bit about the language, and it was fun. No regrets.

But I did learn a thing or two about motivation for language learning. Having a need or a use for the language you’re learning is important. This doesn’t mean that you should choose only super practical languages (Spanish, anyone?), but it does mean that trying to pick up a random language just because it’s kind of interesting probably won’t work. You need stronger motivation.

Aside from motivation, you need occasion to practice the new language. The opportunities for practice and the motivation for learning feed on each other. When you have both, they nurture each other. When you’re missing one, the other easily withers.

As it turns out, I had neither for Korean. I have both for Shanghai sign language, and it’s going really well. I’ll be writing more about that soon.

16

Mar 2009Learning Piano

In my recent post on learning in China, I mentioned that I started piano lessons this month. Some of my experiences illustrate nicely a few of the points I made in that post, so I’ll share them here.

A bit of background first. I studied piano just a little bit when I was in high school. I learned the basics of reading music, the notes of the piano keys, etc. Then, about 6 years ago in Hangzhou, I took piano lessons in exchange for English lessons for about half a year. So I’d say I’m still a beginner, but I’m not starting from scratch.

In my first two lessons I’ve taken quite a bit of criticism from my teacher. I don’t pay enough attention to my finger positioning or movements. My left hand accompaniment is not staccato enough, and my right hand isn’t playing the melody smoothly enough. (Who knew Oh Susannah could be so agonizing?)

So here’s how it works out for me linguistically:

Finger positioning. This requires little to no Chinese to learn. I’m hearing things like 不对 (“not right”) and 手指应该这样 (“the fingers should be like this”), all the while being shown the proper form, or, in some cases, having my fingers bent/moved for me. It may be difficult to conform to all the rules, but it’s certainly not hard to figure out what one is doing wrong, no matter the Chinese level.

Vocabulary. I’m hearing a lot of the same words over and over in my lessons: 节奏 (rhythm), 伴奏 (accompaniment), 断奏 (staccato), 连奏 (legato). Hmmm, do you see something these words have in common?

When I first started my lessons, I knew the word 节奏 (rhythm). The rest of the terms mentioned above all kind of made sense in context, and the second syllable zòu, which they all share, isn’t a very common one in Mandarin. So when it wasn’t entirely clear, I was still guessing that each word was somehow related to rhythm. Still, the frequency that those words came up drilled them into my head, and while possibly related, the terms clearly did not mean the same thing as rhythm. So I was compelled to look each one up when I got home, just to make sure I was understanding my teacher correctly. (You muddle through when you can, but once the repetitions reach a certain level, muddling starts to feel silly.) So I’ve already had those new additions to my vocabulary reinforced more strongly than any other words I’ve learned in a long time. This is learning.

Pedagogical background. The biggest difficulty we’re having communicating is that my teacher expects all her students to be familiar with the do re mi fa so la ti do technique for referring to notes in a scale (those in the know seem to call this solfège), but to me, that’s pretty much just just a song in The Sound of Music. I know the notes, and I’m fine with assigning numbers to them, but if you want me to play mi-mi-fa-re in the key of C right now, I’m lost. Fortunately, my teacher is accommodating and switches to names of the notes that I actually understand… when she remembers. I just give her that blank look every now and then to remind her.

My teacher doesn’t use English with me, but she mentioned that she has one or two foreign students with whom she has to use English. (This reinforces my point that speaking Chinese is not an absolute necessity for this stuff.)

Besides learning a few words, I’m starting to feel that I understand just a bit more of the pain of being a Chinese kid. Fortunately there’s still no Chinese mom making me practice piano when I’d rather go play.

11

Mar 2009iTunes Downloads Almost for Free

Not quite free, but close to it. In China you can buy $200 iTunes gift certificates for 18 RMB (roughly $2.60) on Taobao.

(Can anyone out there confirm this? A quick search turns up a wide range of prices.)

Via Hank.

05

Mar 2009No Excuse Not to Learn in China

Many an eager young laowai has arrived in China with the goal of learning the language. This is an undertaking I whole-heartedly support. But why stop with Chinese? Human labor is high in supply and low in price here, and this principle applies to all kinds of teaching and training services as well.

What can you learn in China besides Chinese? Tons of things. Here are some examples:

- Cooking (there are a million styles of Chinese cuisine, appreciated all over the world)

- Musical instruments (eastern or western, from guzhen or erhu to drums or guitar, it’s all here)

- Sports & martial arts (from tennis or soccer to tai chi or even taekwondo)

- Art (drawing, painting, scultpure, calligraphy, etc.)

- Chess, Chinese chess (象棋), go (围棋), “Connect Five” (五子棋), mahjongg (麻将) etc.

- Other foreign languages or dialects (rather high Chinese level recommended)

The more international your city, the more your options. For example, I know one person studying taekwondo in Shanghai, but taekwondo, not being Chinese, is probably not an option everywhere in China, whereas cooking and musical instruments will be.

I had better head off a few excuses here:

Language is not a huge issue. If you’re a student of Chinese, using and hearing Chinese to learn something else will only enhance and accelerate your acquisition of Chinese. The more physically demonstrable the subject matter (e.g. cooking or musical instruments), the less your Chinese ability will matter. If you’re not studying Chinese or are really just way too early in your studies to apply it to another field of study, you should still be able to find a teacher. Tutoring an English-speaking foreigner is an opportunity that many teachers will jump at; it allows them to practice their English while focusing on exactly the language that applies to their field of expertise.

There are channels to help you find tutors. The Chinese way is to start by asking your friends and acquaintances for recommendations or introductions. In addition, some universities provide cheap tutoring services by offering their students as tutors, and collecting only a small processing fee. Going through such an agency makes it easier to switch tutors if necessary and to add additional study subjects if you so wish. (My alma mater, East China Normal University in Shanghai, offers such a service. I’ve used it in the past, and can attest to both its affordability and effectiveness.) There are also small companies which offer various kinds of tutoring or training at market rates; just ask for some help in finding them.

You have time if you’re really interested. I’ve been feeling especially busy with work lately, but I’m not a machine, so I still take time to relax at night. Watching DVDs or surfing the net are two ways to unwind, but if I’m taking lessons in something I genuinely enjoy, it’s a much more satisfying way to spend my free time. So I’ve just recently signed up for a weekly piano lesson in a small school near my home. (Click here to see what the school charges for lessons.)

I’ve always regretted not studying piano (or some instrument) when I was younger. China has given me a very affordable second chance, although I didn’t recognize it immediately. If, like me, you live in China and have been wanting to take lessons of some kind but denying yourself for some reason or another, hopefully this little nudge will help you to get out there and start learning!

03

Mar 2009Flawed Plan

From Twitter, ajatt says:

> Another problem with going to the country to learn the language is that by design, just as your skill is peaking, it’s time to leave.

I can attest to that. It’s one of the big reasons I never left China.

I once did have a plan to stay in various countries for relatively short periods of time, just long enough to gain fluency. It does make me wonder… who is heartless enough to leapfrog across the globe, mastering one language after another, gaining precious insight into those cultures, only to leave each one behind?

27

Feb 2009The Economist Pwned by China!

Waxy.org has an interesting article called Translating “The Economist” Behind China’s Great Firewall. It tells how underground online organization the Eco Team translates every Economist article into Chinese and puts it online.

The greatest part was a line left by commenter Felipe Li:

> We’re in your websites, translatin’ your language.

Via Hank.

23

Feb 2009Cross-Cultural Marital Communication: Sacrifice, Identity, Choice

Commenter 維特利 recently made this observation:

From reading different blogs I see that there are two kind of situations in mixed families in China:

- American husbands speak Chinese with their Chinese wives and therefore wives aren’t fluent in English.

- Chinese wives speak English with their American husbands and therefore American husbands aren’t fluent in Chinese.

It looks like that real bilingual families are not easy to find:-)

The comment rings true, and it’s something I always suspected was partly due to language-learning motivation of one of the parties. In my case, I preferred not to date Chinese girls that wanted to speak to me in English because I was in China to practice Chinese, and at least this way I could be sure I wasn’t being used. (I wasn’t just using, of course… I did fall in love.) Still, this explanation isn’t terribly compelling. Not every cross-cultural relationship is sparked by a burning desire to learn a language.

A study by Ingrid Piller called Language choice in bilingual, cross-cultural interpersonal communication examined the languages used by German- and English-speaking cross-cultural couples and made some interesting observations.

In the following excerpt from the study, Deborah speaks English and her husband speaks German:

Deborah: […] well, my husband and I decided to speak English together, and I guess mainly that has to do with the fact, that, when I first arrived here in Germany two years ago his English was considerably better then my German, and in order for us to communicate, even on a basic level, it was- it was necessary for us to speak English. And I think we’ve just kept that up, because it became a habit, and also I think it’s sort of a, … a way for him to offer some sort of sacrifice to ME. because I had to give up, all my things, my culture, my language, my family, and my friends, to move to Germany. and he had everything here around him. And I guess the only thing he COULD offer me was his language. […] it- it’s STRANGE for us when we speak German with each other. because we met in the States, he was teaching German at the university where I had studied. and I had already graduated but he was giving me private lessons. and that’s how we became friends, and we just spoke English together THEN. and we have always spoken English together, and it just seems strange that- that once I came here, that we should then speak German. […]

It’s interesting that Deborah sees her husband speaking English as a sacrifice, because I think both my wife and I see our communication in Chinese rather than English as an opportunity sacrifice for her which was necessary not just because I was enthusiastic about learning Chinese, but also because it’s more important for me to be fluent in Chinese in China than it is for her to be fluent in English in China.

The excerpt above was followed by this analysis (bold mine):

Deborah finds it strange to use the majority language with her husband because that is not what they did when they first met. The fact that couples find it difficult to change from the language of their first meeting to another one can probably be explained with the close relationship between language and identity. In a number of studies in the 1960s, Ervin(-Tripp) (1964; 1968) found that language choice is much more than only the choice to the medium. Rather, content is affected, too. In a number of experiments, that have unfortunately not been replicated since, she demonstrated that in Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT) the content of picture descriptions changed with the language (English or French) a person used. When she asked English-Japanese bilingual women to do a sentence completion test, she got the same dramatic results: the sentence completion changed from one language to the other. Her most famous example is probably that of a woman completing the stimulus “When my wishes conflict with my family…” with “It is a time of great unhappiness” in Japanese, and with “I do what I want” in English (Ervin-Tripp 1968: 203). Likewise, Koven (1998) shows in her study of the narratives of French-Portuguese bilinguals that the self is performed differently in these languages. She argues that these differing performances point to contrasting experiences and positional identities in the two linguistic communities. So, there is evidence that bilinguals say different things in different languages, which makes it quite obvious why intercultural couples stick to the language of their first meeting: they might lose the sense of knowing each other, the sense of connectedness and the rapport derived from knowing what the other will say in advance if they switched.

Very interesting (and a little scary).

Yet I’d still like my wife to know the English-speaking me better, and I would hope that someday not too distant the Chinese-speaking me can converse with a bit more sophistication. Meanwhile, the English-speaking her is shy, but shows a lot of promise.

People change. Identities evolve. Maybe it’s not the norm, but I imagine marital language relationships can develop too.

21

Feb 2009Counterfeit Money, Payrolls, and Banks

I received this e-mail from a reader recently:

I just read your piece on counterfeit money. I work for a school in a western province which paid me just before NY. About one third was counterfeit money which I’m having a tough time with, groceries to buy, transportation and so on; nobody wants to take my money and school isn’t back in for another month. My employer is out of the country and doesn’t return my emails. What to do with counterfeit money which he got from the bank himself?

I wasn’t sure how to answer this… My first thought was that the employer was lying, and he didn’t really get it from the bank. He might easily have bought a bunch of counterfeit bills himself, and cut all his employees’ paychecks (or maybe just certain ones’) with them to save money on his payroll.

That said, I live in Shanghai, and I’m not sure how things work in the “western provinces.” The banks themselves could be mixed up in counterfeiting as well. Does anyone have any experience? (中国朋友,不要害羞!写中文也可以。)

16

Feb 2009Comic Reduplication Meets Historical Reduplication

“Reduplication, in linguistics, is a morphological process by which the root or stem of a word, or part of it, is repeated” (Wikipedia). You see reduplication in Chinese a lot, with verbs (看看, 试试), nouns (妈妈, 狗狗), and even adjectives (红红的, 漂漂亮亮).

You get reduplication is Japanese too (some of the coolest examples are mimetic), in words such as 時々 or 様々. As you can see, rather than writing the character twice, the Japanese use a cool little iteration mark: 々. Now if the Japanese learned to write from the Chinese, why don’t the Chinese use the same iteration mark?

According to Wikipedia, the Chinese sometimes use 々, but you don’t see it in print. This is true; what the Chinese use (only when writing shorthand) actually looks something like ㄣ. Ostensibly, because you never see 々 in print in China (or it never even existed in neat, printed form), it comes out a bit sloppily as ㄣ in Chinese handwritten form.

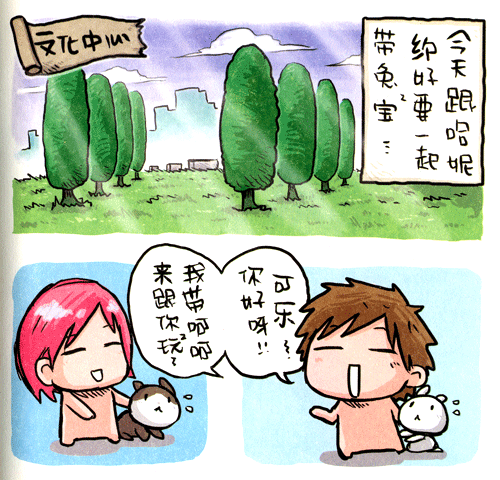

I recently read a cutesy Taiwanese comic called 兔出没,注意!!! Rabbits Caution about the lives of two rabbits named 呵呵 and 可乐 and their owners. In the comic, the author took a rather “mathematical” approach to reduplication. Look for 宝宝 and 玩玩 in this one:

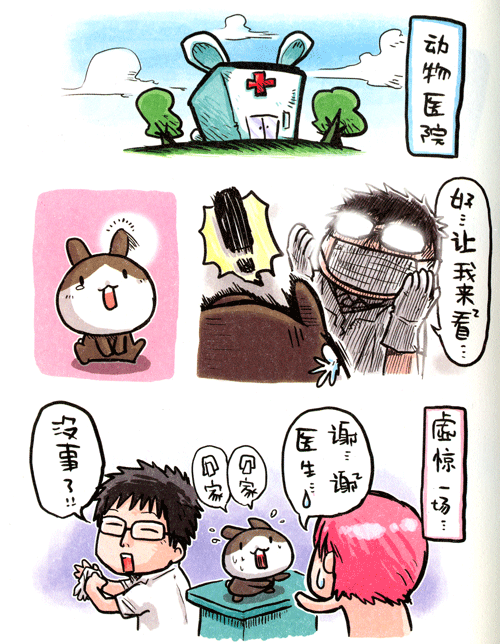

Look for 看看 and 谢谢 in this one (and don’t be confused by the 回 in 回家):

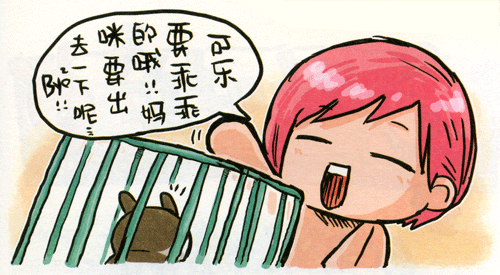

In this frame, even “bye-bye” gets the treatment:

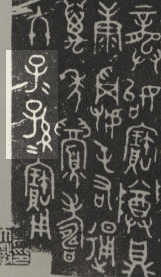

While cute, I figured this representation of reduplication was not likely original. I was quite surprised, however, to see an almost identical representation on Wikipedia dating back to 900 B.C.! The quote:

The bronzeware script on the bronze pot of the Zhou Dynasty, shown right, ends with “子二孫二寶用”, where the small 二 (two) is used as iteration marks to mean “子子孫孫寶用”.

Well, as they say, there’s nothing new under the sun, and history repeats itself. The weird thing is that 2 and 々 even sort of look alike, in the way that 々 and ㄣ do. 2 is 々 without the first stroke, and ㄣ is 々 without the last stroke. Meanwhile, the ancient Chinese iteration mark 二 bears a striking resemblance to the modern “ditto mark” used in modern English! (I’ll leave those for the orthographical conspiracy theorists among you to chew on.)

11

Feb 2009Mark's New Pinyin Input Firefox Extension

My friend Mark has created a FireFox addon. It does one thing and it does it well: it converts onscreen text from numeral pinyin to pretty pinyin with tone marks. (It doesn’t convert characters to pinyin or any of that jazz.)

I find this very useful. If it sounds good to you, try out the Pinyin Input Firefox Extension.

09

Feb 2009Buying a Wii in China

A while back I blogged about buying a PS2 in China, and there was a lot of interest. There’s not much to say about PS3, because it is so far uncracked/unpirated, so everyone who plays PS3 here imports everything. Games are 2-300 RMB each. XBox 360 has similar status re: pirating to Wii in China, but I have almost no experience with it, so will limit my observations to the Wii and its games.

Nintendo does not officially sell the Wii in the People’s Republic of China, so buyers must purchase an imported system. While previously Japanese Wii systems were the most common, now Korean imports are becoming more common. I imagine it is possible buy the Wii imported from the United States and other countries as well.

These are the prices I was quoted at my local video game shop:

– Basic Wii system (one controller) imported from Korea: 1580 RMB

– Installation of WiiGator “backup launcher” (which allows you to play “backup copy” AKA pirated games): free

– Extra Wii controller set (Wii remote + “nunchuk”): 450 RMB

– Wii Fit imported from Japan (with Wii Fit game/software): 800 RMB

– 10 games (not imported, obviously) – free

All games work fine as long as you load them through the WiiGator Gamma Backup Launcher 0.3. The system also comes preloaded with Homebrew and Softchip (an alternate backup launcher). The shopkeeper told me only to use the WiiGator Gamma Backup Launcher, but I did actually try out the Softchip launcher, and it worked for most games. The (Korean) Mii section, however, does not work at all. I’ve heard that it can easily be enabled; the shopkeeper I talked to said it’s a waste of precious memory. I didn’t buy any memory upgrades, and so far I’m doing fine without it.

Just like PS2 and XBox 360 games, Wii discs sell in Shanghai for 5 RMB each.

It is expected that “backup launchers” and other alternate Wii firmware will continue to make strides. Currently, for example, online access is impossible, and attempts to use it will likely lock down the offending Wii system. In the event that alternate firmware does release better versions, it’s understood that shopkeepers will upgrade the firmware of their customers’ systems free of charge.

I can’t actually help you buy a Wii; this information is for reference only. If you’re interested, please also see Buying a Wii in Taiwan, a sister blog post by my friend Mark, who lives in Taiwan.

05

Feb 2009Where Futurama and Queen Meet

Despite the fantastical title, this is a blog post about translating into Chinese. Bear with me here.

Although she recognizes its importance, my wife has never been very enthusiastic about studying English, so over the years I’ve tried various ways of encouraging her to study. One of the earliest ideas I had was the TV show Friends. Tons of young Chinese people love it as study material, and ever since my teaching years in Hangzhou, I’ve always felt it’s great for that. (I’m not one of those Friends-bashers.) My wife, however, hated it. She thought it was dumb.

Eventually, we found the English TV show that she liked. To my surprise, it was Futurama. Now don’t get me wrong… I love the Simpsons, and I love Futurama, but I really didn’t expect my wife to like it. But she really, really did. (She continues to surprise me on a regular basis.)

So we found the English language TV show she wanted to watch, but she still wanted Chinese subtitles. And so the great “Hunt for Futurama-with-Chinese-Subtitles” began.

This turned out to be way more difficult than I imagined. We asked a lot of shops for a long time, and in the end we only ever found Season 1 with subtitles. In the process, however, I became familiar with Futurama’s Chinese names.

Yes, that’s names, because it has a few. It seems like the most popular one is 飞出个未来. Taken literally, it doesn’t make much sense… something like “fly out a future.” I guess it sort of jives with Futurama’s opening sequence, but what the name is actually doing is approximating the sound of the English word “future” with the Chinese word 飞出. Kinda clever, if crafty transliteration is your bag, but certainly no masterpiece of translation.

The translation I like better is the one I first learned: 未来狂想曲. The first part, 未来, means “future.” OK, fine. But here’s where the interesting part comes. The next three characters are supposed to somehow represent “-rama” in Chinese. Considering that I’m not even sure how to explain what that means in English, I really feel that “-rama” is not easy to translate into Chinese, especially considering that this time the transliteration copout was not used.

The second part, 狂想曲, if broken down into three characters, literally means something like “crazy imagination tune.” It’s a real word that means “rhapsody” (in the musical sense). According to wikipedia:

> A rhapsody in music is a one-movement work that is episodic yet integrated, free-flowing in structure, featuring a range of highly contrasted moods, colour and tonality. An air of spontaneous inspiration and a sense of improvisation make it freer in form than a set of variations.

I think that description matches “-rama” and the feel of Futurama quite well, actually.

Still, if you’re a non-musician like myself, when you hear the word “rhapsody,” there’s a good chance you make this association:

Sure enough, “Bohemian Rhapsody” is 波西米亚狂想曲 in Chinese. I even found a website that translates all the lyrics of the song into Chinese. Just go to this 波西米亚狂想曲 page and watch the text to the right of the video as it plays. The translation isn’t 100% accurate (the translator also wimped out on “Scaramouche”), but it’s pretty decent. And more than a little awesome.

Sadly, the 未来狂想曲 translation of Futurama is seldom used, and has even been co-opted by a TV show called The Future is Wild. Ah, well. Easy come, easy go… doesn’t really matter to me.

02

Feb 2009John DeFrancis

I’ve been feeling guilty for a month for not saying something about John DeFrancis’s passing. I have have no words more eloquent or meaningful than these three, however:

– Victor Mair (on Language Log)

– David Moser (on The China Beat)

– Brendan O’Kane (on his site)

Not surprisingly, I especially liked (and identified with) Brendan’s. If you don’t know DeFrancis and you’re at all interested in Chinese, by all means, check out the man’s work.

I’m also a little embarrassed to admit that it wasn’t until recent word of DeFrancis’s death that I realized when it was that I first read The China Language: Fact and Fantasy. While I was studying in Japan in 1997, I checked it out from the Kansai Gaidai library. It was perhaps that book, more than anything, that kindled the spark of interest I had in Chinese, impelling me to formally study it after I went back to the U.S., and ultimately to travel to China after graduation.

Thank you, John DeFrancis.

31

Jan 2009Character Check!

On the historic eve of Obama’s inauguration, I just happened to run into these two signs, both on Tongren Lu (铜仁路).

Notice anything strange? (And for extra points, do you know where I saw these? If you’re a foreigner living in Shanghai, there’s a good chance you’ve seen them.)

29

Jan 2009Video Games for Lunch

Happy 牛 Year and all that. I took a bit of a break from blogging this month, and I’ve got a bit of a backlog of things to write about… many just tiny observations like this one.

Last week my wife and I went to DeAll Korean restaurant in Hongqiao for the lunch buffet. The restuarant is typically full of Koreans at lunchtime.

We were amused by the “interaction” at this table of kids:

(Hey, what else are you going to do at lunch?)

22

Jan 2009Elvis Does Tang Poetry

This is an odd combination:

The video is a promotional thing for a new podcast show on ChinesePod called Poems with Pete.

19

Jan 2009Looking Both Ways

I was reading the book Nudge recently, and this passage struck me as odd:

> Visitors to London who come from the United States or Europe have a problem being safe pedestrians. They have spent their entire lives expecting cars to come at them from the left, and their Automatic System knows to look that way. But in the United Kingdom automobiles drive on the left-hand side of the road, and so the danger often comes from the right. Many pedestrian accidents occur as a result. The city of London tries to help with good design. On many corners, especially in neighborhoods frequented by tourists, the pavement has signs that say, “Look right!” (91)

I learned to drive in high school as a 15-year-old through a driver’s ed class. The only really vivid memory I have of that class occurred in a road test. The instructor was in the passenger seat, and he had his own brake. I was stopped at a red light.

When the light turned green, I confidently stepped on the gas. The instructor immediately broke hard, giving me quite a jolt. I glanced up to see that, yes, the light was green. I turned to the instructor, expecting an explanation for his mistake. But no, he was livid.

“What are you doing?” he demanded.

“I’m going straight. The light’s green!” I replied.

“Did you look to see if there were any cars coming from the left or right?”

“No, but the light was green,” I insisted weakly.

“You didn’t even look, and that can get you killed. I don’t care if the light is green. You still have to look.”

The key part of the Nudge passage was this: “who come from the United States or Europe.” Drivers from those countries have very rigid expectations for pedestrian behavior. Likewise, traffic patterns are so regular and predictable that pedestrians only really need to look one way when they cross the street, no matter what they supposedly learned in driver’s ed.

It’s easy to call traffic in countries like China or Mexico chaotic and uncivilized, and there’s clearly some progress to be made, but isn’t it better for pedestrians to be putting a bit more effort into protecting their lives? Isn’t it better for drivers to be a bit more alert for unpredictable pedestrian behavior?

At the very least, I’m pretty sure after living in China, I don’t have to worry too much about crossing the street in London.

07

Jan 2009Context Is Everything

I was at a dinner, listening to the conversation of some Chinese acquaintances. At one table, two young women sat side by side. In the context of their conversation, one of the women said, pointing to the other:

> 我是女的,她是男的。

The grammar of this sentence is so simple that any first semester student of Chinese can figure it out. But without the proper context, they’re probably going to conclude that one of the women was actually a transvestite: I’m female. She’s male. (She wasn’t a transvestite, and no one listening found her statement strange in the slightest.)

The two women were talking about their newborn children, when one of their friends asked what sexes the babies were. So 我是 and 她是 were easily understood to mean “my baby is” and “her baby is.” This is totally fine in Chinese.

(You also get lots of statements like this when people are ordering food… I’m beef noodles. You’re dumplings, right?)

Context is everything.

05

Jan 2009Spelunkying

While I’d like to kick off the new year with an interesting post about language, I’ve been enjoying myself too much recently to put one together. I’ve become addicted to a cool independent game called Spelunky.

Spelunky has cool retro pixel graphics. It’s kind of like Super Mario Brothers (physics) + Zelda (items) + Indiana Jones (theme). What really makes it unique, though, is its random level generation. The game most famous for this is the old 1980 classic Rogue, but Spelunky does it in a more sophisticated, fun way.

You play randomly generated level after randomly generated level, knowing you will never play them again. And you die many, many times. Randomly generated levels strewn with enemies and traps are often very unfair, yet the design is sufficiently balanced and full of surprises that you keep coming back for more… again and again and again.

Well done, Derek Yu. It’s innovative games like this that make me glad I still have a PC and not just a Mac.

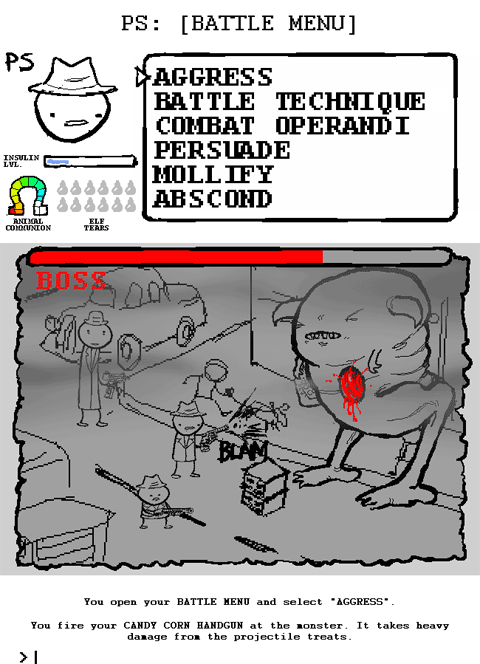

Another noteworthy diversion I’ve spent some time on lately is MS Paint Adventures, a webcomic recommended by Ryan North of Dinosaur Comics. I say “webcomic” because, well… it’s kind of weird. It’s a webcomic pretending to be a Choose Your Own Adventure, posing as a late 80’s Sierra adventure game (think King’s Quest or Space Quest), with elements of RPG and other adventure game genres.

This one’s not for everyone, as you can probably guess by the above image. If you got all the references in my description above, though, you just might like it a lot.

Have a great 2009… and don’t forget to play!

29

Dec 2008Recasting in Language Learning

If you’re a language teacher, you’re probably quite familiar with the concept of recasting, even if you don’t know the name. And if you’re a language learner, being aware of recasting can help you learn faster. So what is recasting?

It comes from the idea of “casting a mold,” but when the student hasn’t properly used the “mold,” you “cast again” (recast).

Fukuya and Zhang define a recast as “implicit corrective feedback.” Another definition of “recast” given by Han Ye in a presentation at the ACTFL 2008 conference was “a native speaker’s corrective reformulation of a student’s utterance.”

It’s not very complicated in practice. Here’s a simple example:

Student: I want read.

Teacher: Oh, you want to read?

In the above example, the English teacher communicates with the student (using a question to confirm what the student had said), while at the same time making a correction (adding “to”). The teacher may or may not choose to emphasize the correction.

Here’s a slightly more subtle example:

Student: I want read.

Teacher: What do you want to read?

In this example, while you could identify a correction in the teacher’s question, the focus is more on communication and less on correcting the mistake.

Recasts don’t have to be questions, and they can be focused on pronunciation, on grammar, on vocabulary… but they always carry with them some degree of ambiguity, because recasts are not overt corrections, and some degree of repetition is a natural part of normal speech. Will the student pick up on the correction, or will the conversation just keep moving along? (Does it even matter what the student consciously notices his mistakes?)

I believe that much of my own success in acquiring Chinese has been due to (1) getting lots of practice with native speakers, and (2) being receptive to recasts.

Here’s a typical example of an exchange that might occur (in Chinese), with a string of letters representing the focal language point:

Learner: Abcde.

Native speaker: What?

Learner: Abcde.

Native speaker: Ohhh… AbcDe!

Learner: Yes, Abcde.

The native speaker’s second utterance above was a recast, but as we see in the last line of the exchange, the learner didn’t get it. Yes, the recast was almost imperceptibly different from what the learner said originally, but recasts tend to be that way (from the learner’s perspective)… especially when they involve tones. As a learner, when you become more sensitive to recasts, you’ll hear them all the time.

Think about it… some people will pay big bucks to a teacher in order to obtain explicit corrective feedback. In actuality, though, if that person is in a second language environment, he is probably getting corrective feedback all the time in the form of recasts and not even knowing it.

Recasts are great because they don’t impede the flow of information and they’re usually not an embarrassing form of correction. They’re also great because you don’t get them if you don’t get out there and talk to native speakers. They’re a positive side effect of speaking practice. As a learner, recasts are your friend.

At ACTFL 2008, Han Ye of the University of Florida presented the findings of an experiment on tonal recasting. The experiment sought to compare the effect of recasts on Chinese heritage learners with the effect of recasts on non-heritage learners. The recasts were all for tone-related errors.

Interestingly, the study found that the uptake rate for non-heritage learners was 51%, but only 28% for heritage learners.

I found this interesting for a number of reasons. The Chinese heritage learners were likely much more confident in their ability to communicate, and probably less self-conscious about their Chinese. The non-heritage learners are more receptive to feedback, but do they communicate as well?

It is likely that the role of recasts is most important in the early stages of learning a language. Our own parents used recasting on us plenty when we were children still learning our mother tongues, but eventually, either they stop doing it or we stop paying attention.

There are a lot of factors at play here, not the least of which are individual learning styles and learner personality. Recasting research continues.

I’m just one of those people that likes to pay attention to recasts.