13

May 2009Many Eyes on Language

The “Language Speakers” bubble chart image below was created as part of IBM’s Many Eyes project:

It’s a really cool project which enables the creation of various types of visualizations given certain data sets. Language lovers will also be interested in the Phrase Net on the Many Eyes blog.

11

May 2009Cultural Universals

I’m not sure if the people in this picture are Chinese, but I found it through Baidu Images:

This reminded me of a similar funny photo I’d seen before. Turns out there are quite a few, if you look. Here’s one gallery, and another with more photos, and of a more international nature (but also more NSFW).

09

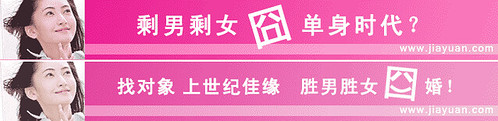

May 2009Jiong Permutations

The 囧 (jiǒng) phenomenon has been around for a while now, and I’m starting to see more and more permutations of it. Here are a few examples.

From an online Chinese ad:

From TofuBrain‘s Flickr page:

From a local shop:

What have you seen?

Flickr updates:

This photo by 强悍的兔子.Rabbit has many permutations:

Also, these two examples of 囧 showing up in the character 明…

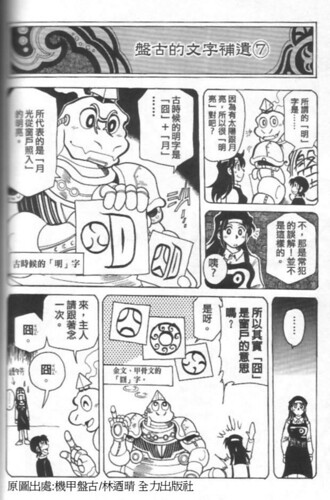

…are explained by this comic [large size]:

The comic says that the character 明 actually derives, not from 日 and 月 as is commonly taught, but from 囧 and 月. This etymology seems to confirm it. So one of the earliest character etymologies we learn (sun + moon = bright) is either a lie, or actually just a bit more ambiguous than we were led to believe? Interesting!

03

May 2009Visa Fest!

My blog posts about visas probably generate more e-mails from random strangers than anything else. This suggests to me that a lot of people are out there scouring the internet for more info on the subject, so I’ll share a bit more. In the past two weeks, I have been involved, to some extent, with 5 Chinese visa applications: three to the USA, one to Japan, and one to Thailand.

USA

It’s been a while since my wife and I had to go through the visa ordeal. Now we’re married, and we want to take her parents with us this summer so they can see Florida as well. We were a bit worried that it would seem like the whole family was trying to immigrate to the US, but all three of them got their visas.

Some relevant details:

– My father-in-law has been to the USA once before in 1992; my mother-in-law has never left China

– My in-laws own property in Shanghai and have savings

– My wife was in the USA last in 2005

Japan

I haven’t been to Japan in close to five years, and my wife and I have been meaning to make a trip for a while. We finally settled on this May, but realized we had a visa problem: the typical Chinese tourist to Japan must go with a tour group and stay with the group the whole time. I refused to do that, and my wife didn’t want to either. We wanted to hang out in the Kyoto/Nara/Osaka area and take it easy, rather than the typical tour’s “10 cities in 5 days” approach. If we didn’t want to go on a tour, though, we would have to get my wife’s visa “sponsored.”

The process is kind of complicated, so I won’t go into it to much here [Chinese link, Japanese link], but the bottom line is that your Japanese friend needs to supply a lot of paperwork, including:

1. Proof of a relationship with the Chinese visa applicant

2. Acceptance of responsibility if the Chinese visitor remains in Japan illegally

3. Lots of personal information, including tax information

In the end, our visa application failed because our visa sponsor filled out the form with all the tax information but didn’t include full information for their income history. After several mail exchanges between China and Japan (faxes are no good for this procedure), we were already cutting it close time-wise with our application, and we didn’t have enough time to fix the last problem.

Really, though, we didn’t want to fix the last problem! My former homestay family was so nice about sponsoring my wife and filling out all the paperwork — even including their tax information — and I really did not want to ask for even more personal financial information. It just doesn’t seem right. I’m close to my former Japanese homestay family, and they attended our wedding in Shanghai, but asking for someone’s tax and income information is just not cool. What a shitty passive-aggressive way for the Japanese government to discourage Chinese tourism.

Fortunately, the situation is changing as early as this fall, as Japan changes its regulations to let in individual Chinese tourists that are rich enough.

Thailand

Thailand is one of the easiest countries for the Chinese to get a visa for. Even with the recent unrest, while tours have paused temporarily, individuals can still get visas easily.

So forget Japan… we’re going to Thailand!

26

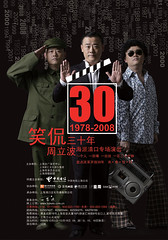

Apr 2009Shanghainese Stand-up Comedian Zhou Libo

I haven’t noticed any online English language mentions of Shanghai comedian Zhou Libo (周立波) yet, but he clearly deserves a bit more attention. His DVD, 笑侃三十年, has been selling like hotcakes in DVD shops across Shanghai for weeks, and I hear his upcoming live performances are selling out.

You could say his act is “comedy with Shanghainese characteristics” because 笑侃三十年 is Zhou’s humorous take on the changes Shanghai has experienced in the past 30 years. For many Shanghainese, the act is equal parts nostalgia and comedy. (Well, maybe not equal… my wife was laughing so hard she was crying at certain parts, and she’s not old enough to be nostalgic about everything he was talking about. Her parents loved the act too, though.)

Of course, the most obvious “Shanghainese characteristic” of Zhou’s act is the language it’s delivered in. Being mostly in Shanghainese, Zhou Libo’s humor remains somewhat inaccessible to both foreigners and most Chinese alike. Sure, there are video clips online with Chinese subtitles, but when he starts with the Shanghainese wordplay, subtitles are of little use.

Chinese media comentator David Moser has lamented the death of xiangsheng as an art form in China. So what’s filling the void? To me, one of the most interesting aspects of the Zhou Libo phenomenon is that he seems to be a part of a larger development: as two-man “Chinese stand-up” xiangsheng is waning, a new brand of home-grown Chinese solo stand-up comedy may be emerging. Furthermore, it seems to be happening through quirky regional acts like Xiao Shenyang from northeast China (the act linked to can only be described as stand-up comedy), and Zhou Libo, whose act is so “regional” that it can only be directly appreciated by the Shanghainese.

I’m certainly no expert on stand-up comedy, but I’m interested in seeing where this is going. Perhaps sites like Danwei will do some more in-depth reporting on the phenomenon, even if a Shanghainese act is of little interest to Beijingers.

25

Apr 2009Civilizing Me

Earlier this week I set out for work one morning only to discover that my bike was missing. It wasn’t where I parked it in my apartment complex, and it wasn’t anywhere nearby. I was surprised that a bike as uncool as mine, with both wheels locked, would be stolen from my apartment complex, but these things happen every day. I walked to work.

That night I decided to look for my missing bike a little more. The thing is, I had parked in an area I’m not technically supposed to park in. There’s a sign on the wall that says “don’t park here please,” but after seeing other bikes parked there on a daily basis for months on end, I decided to join them. It’s a more convenient parking place. (The proper place is underground, requiring use of the stairs.)

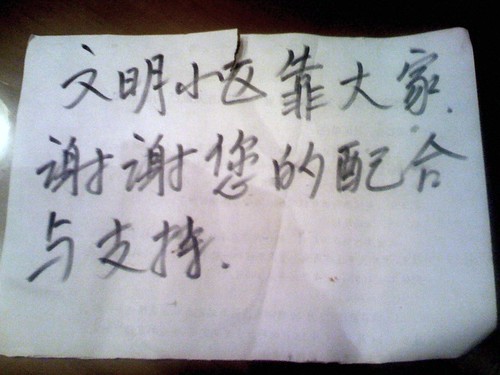

So I didn’t want to ask the guards, because that would mean admitting that I parked in the wrong place. I went to the nearest underground parking section, and sure enough, there was my bike. It had this note attached:

Transcript:

> 文明小区靠大家

谢谢您的配合

与支持

Translation:

> A civilized community depends on everyone.

Thank you for your cooperation

and support.

I had thought my bike was stolen all day, and I don’t appreciate that. But I’m really glad to see the rules being enforced a bit more. All around me, I see rules ignored on a daily basis: traffic lights, various kinds of queues, no smoking policies, etc. It’s good to feel a little progress. I’m happy to be civilized.

19

Apr 2009Cell Phone Eavesdropping Tools in Shanghai

The other day a friend told me that there was some kind of cell phone wiretapping device being used on her friend. The guy was sure he was being eavesdropped on, because immediately after discussing sensitive information on a special deal with a supplier, a competitor immediately called the same supplier offering a better deal with almost the same terms. The supplier called him back, wanting to know what was going on, and how the other company could have known about the deal.

I quickly forgot this story… industrial espionage is not something that I think about much. But a week or so later, I received this spam message via SMS:

> 专业制作移动,联通卡,做出来的卡能窃听对方所有通话及收发短信,测试满意付款。电话150xxxxxxxx林经理

Translation:

> Professionally manufactured China Mobile, China Unicom cards which let you listen in on someone’s every call, as well as send and receive their text messages. Test first, pay if satisfied. Phone: 150xxxxxxxx Mr. Lin.

So I guess these 窃听 (eavesdropping) things are becoming fairly common now. There seem to be a few similar devices on Taobao too.

14

Apr 2009The Menu Stealer

It’s been a busy week at work, but it’s great to see one long-term project finally coming to fruition: today ChinesePod released the long-awaited first episode of its new video series, The Menu Stealer:

The Menu Stealer – episode 1: Guilin Mifen from PraxisLanguage on Vimeo.

11

Apr 2009A Hostel for Punsters

There’s a hotel on Shanghai’s West Zhongshan Road (中山西路) that I pass pretty often. Its Chinese name is 驴馆, or, literally, “Donkey Hostel.” Its English name is Red Donkey Hostel [website]. (Unsurprisingly, they passed on the opportunity for the similarly puntastic “Ass Hostel” English Translation.)

The Chinese name 驴馆 is a pun on the word 旅馆 (hostel). 驴 (donkey) and the 旅 in 旅馆 (hostel) are both pronounced lü. Even though 驴 is second tone (lǘ) and 旅 is third tone (lǚ), tone sandhi rules render their pronunciations identical in this case.

Here’s a (semi-fictional) image of what the hostel looks like:

See also: other articles on Chinese puns

08

Apr 2009Translator Interview: Megan Shank

Megan Shank has a background in journalism (both freelance and as former editor of Newsweek Select in Shanghai). She has recently relocated to New York City after living in both Dalian and Shanghai. She also keeps a blog. This is the sixth and final interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

I’m primarily self-taught (many hours writing and rewriting characters at the kitchen table) and have also worked with some tutors. For two semesters, I took advanced intermediate Chinese classes at the Dalian Foreign Languages University. I never took a translation class, though I’m still interested in enrolling in some sort of program to improve my skill and speed.

2. How has living in China helped prepare you to become a translator?

For me, living in China has proved essential to my Mandarin studies. Opportunities abound for students to directly apply and test what they’re learning; they can use the language to create real connections. In terms of reading and writing, the characters fly out at you on the street, on a menu, in the subtitles of the late-night news. They dazzle and envelop you; you can’t escape them. Finally, in my experience, I’ve discovered the Chinese love their language. People from cabbies to park-side chess sharks have patiently drawn out characters for me on their palms and explained the radicals. I owe much to these patient and priceless—literally free—teachers.

03

Apr 2009Translator Interview: Benjamin Ross

Benjamin Ross is a translator, interpreter, and adjunct ethnographer living in Chicago. Previously, he has lived in Fuzhou, China, where his blog became well known for his account of thirty days in a Fuzhou barber shop. This is the fifth interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

I have never done any formal Chinese studying. Instead I studied French for 5 years in high school/college, which was a colossal waste of time due to both the limitations of learning a language in a classroom setting, and the dearth of opportunities to speak with native French speakers in Kansas.

Mark Twain once said, “I never let my schooling interfere with my education,” and this has always been the philosophy I have used for learning languages. If I had to say how I studied Chinese, I did it by conversing with old people in the park, traveling around China by train, chatting daily on QQ, learning songs for KTV, carrying around notebooks wherever I went, and asking an endless amount questions to any one of the 1.3 billion Chinese people who were within my immediate vicinity.

2. How has living in China helped prepare you to become a translator?

Living in China has been absolutely integral in preparing to become a translator in that it gave me both the desire and the necessity to master the Chinese language. To further expound on the original question, I would like to modify the question to read “How has living IN A SMALL TOWN in China helped prepare you to become a translator?” My first fifteen months in China were spent in Fuqing, a small town about an hour away from Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian province. I was one of only two Westerners in the entire town, and this more than anything fueled my desire to master Chinese. I honestly think that had I spent those first fifteen months in Beijing, Shanghai, or even Fuzhou, I probably wouldn’t have the appropriate skills to be a translator today.

02

Apr 2009Translator Interview: John Biesnecker

John Biesnecker has worked in Shanghai as a translator for several years, both as a salaried translator and as a freelance translator. He is a language-learning enthusiast, and writes a blog called Never Stop Moving. This is the fourth interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

I took two semesters of Chinese at university, the year before I came moved to China, in classes full of Chinese American kids that already spoke the language. Upon moving to China I discovered that I had learned effectively nothing. 🙂 In 2004 I spent a semester at Jilin University, but mostly didn’t go to class because I was broke and had to work. Everything else has been self-taught.

2. How has living in China helped prepare you to become a translator?

Living in China has made massive input a lot more practical. I don’t think you have to live in China (or Taiwan, or any other Chinese-speaking place) to develop your Chinese skills to the point that you can do translation, but if you don’t you have to be a lot more disciplined. Personally, had I not been surrounded by the language every single day, I don’t think I would have been able to do it. I just didn’t have the “Chinese acquisition drive” to do it in any other way, especially in the beginning.

01

Apr 2009Translator Interview: Joel Martinsen

Joel Martinsen is a well-respected regular contributor to Danwei.org, where his frequent translations are a staple. Joel spends a ton of time immersed in Chinese texts, and according to Brendan, “he never forgets anything he ever reads.” This is the third interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

My high school offered Chinese as a foreign language, which turned out to be somewhat less effective than other high school language programs because all levels were tossed together in one class. I took Chinese as my foreign language in college, reaching a third-year level, and then came to China after graduation. After three years living in Jilin, I enrolled in a graduate program in the modern literature department of Beijing Normal University, where I left after three years without actually completing a degree.

2. How has living in China helped prepare you to become a translator?

Access to books and other materials, particularly print journalism, was one of the great benefits of living in China. Being able to take a short walk and pick up an interesting used book from a street vendor or the latest issue of a news magazine probably got me to read more at a time when slogging through classics or being bored to tears by children’s fables would have driven me to put down the books in favor of something less helpful to my language learning. And the sentimental, overacted TV dramas that play at all hours are a great way to get a sense for how

colloquial language is actually put to use. Most of this is probably available on the Internet these days, though. It was after I started doing translation work that other advantages became apparent. The community of translators in Beijing has helped me find work, tackle sticky problems, and figure out standard rates and typical client expectations so that I’m not underselling my efforts too badly. This is doable over the Internet too, but it would require more motivation than I possess. It’s great to be able to call someone up a native-speaker friend with a translation issue and then meet face to face to hash it out in a conversation that could go on for several confusing rounds over email. For some work, such as film subtitling, living in China (or at least being able to fly over for the

duration of the job) is essential.

31

Mar 2009Translator Interview: Peter Braden

Peter Braden is ChinesePod‘s translator, as well as host of Poems with Pete, a podcast which introduces Chinese poetry to a general audience. He is a voracious reader, Elvis impersonator, karaoke king, and proud couchsurfer. This is the second interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

I studied for two years at the State University of New York, Albany and one year at the International Cultural Exchange School (国际文化交流学院) at Fudan University here in Shanghai. I didn’t learn very much in the first year at SUNY. This was partly because the teacher emphasized atonal pinyin above all else, and partly because I hadn’t “caught the bug” and didn’t apply myself completely. Everything changed in the second year when I got an outstanding teacher who put the “fun” in fundamentals. He was much more aggressive about radicals and tones. I got very interested, and knew I needed to learn more.

In addition to the pure language courses, I took a lot of other courses on Chinese history for my double majors, Asian History and East Asian Studies. This included research trips to Tibet and Xinjiang. I also lived in a Buddhist monastery in Kaohsiung (ROC) for a month. These courses got me even more excited to learn Chinese, so that I could read historical documents, interview people, and do research. You can’t learn (or at least you won’t really enjoy learning) Chinese in a vacuum. You need a motivation, or the language will grind you into powder and blow you away.

30

Mar 2009Translator Interview: Brendan O'Kane

Brendan O’Kane is a talented young writer, much beloved in the China blogosphere scene for his pieces on Bokane.org. He has also earned much praise for his amazing spoken Chinese and understanding of Chinese poetry and classics. This is the first interview in a series entitled The Many Paths to Translation Work.

1. What formal Chinese study programs have you participated in?

My study history has been kind of a patchwork. I began learning Chinese with evening classes at the Community College of Philadelphia in September 1999, and continued there until December 2000 when they didn’t get sufficient enrollment for the spring 2001 semester. After that, I got private lessons with my old professor’s husband for a semester, then joined the Stanford/Beijing University summer program from June-August 2001. When I started at Temple University in fall ’01, I went into third-year Chinese with Louis Mangione (who is worth his weight in gold as far as I’m concerned) and took a semester of independent study classes in Classical Chinese in spring ’02.

After that it gets a bit messy: I spent a year teaching in Harbin from 2002-2003, which was just wonderful for my Chinese — though I doubt it was much help for my students’ English. After a year of teaching little kids, I decided I’d rather be a student than a teacher, at least for a while, and went back to Beijing University through its 对外汉语学院 [College of Chinese as a Foreign Language] from fall 2003 to spring 2004. I found that the advanced classes there were not really much help, so after a semester of language classes, I switched to regular undergraduate classes in the Chinese department. I don’t think I made the most of that opportunity, and still regret being basically a slacker during that time — but I did manage to get a fair amount out of it with courses in 文字学 [graphology]、《老》《庄》导读 [guided readings in Laozi and Zhuangzi]、and 现代汉语语言学 [modern Chinese linguistics].

And that’s pretty much the end of my formal training. When I went back to the States to finish my degree at Temple, I took a couple of independent study classes in which I decided to focus on my written Chinese (a topic that i don’t think any program really addresses in any kind of serious way), and after a year of that, I came back to Beijing, where I’ve been ever since.

I wouldn’t want to downplay the help I’ve gotten from my teachers, but I think I also got a lot out of studying and reading up on things on my own. I’ve been raiding second-hand bookstores (and first-hand bookstores, when I’ve got the money) pretty much since the beginning of my study of Chinese, and I think my extracurricular reading has been a huge help in my studies. Being in China for a lot of it has also helped a lot, obviously, but I’m not sure I would have gotten the same benefit if I’d been here from the start of my studies — but that takes us to:

29

Mar 2009The Many Paths to Translation Work

I succumbed to the lure of translation work just as I was about to start grad school in 2005. Although I had long avoided “real translation work,” I figured if my Chinese was good enough to get into grad school in China, then I should be able to handle a few translation jobs. The truth is, even after 4+ years of living in China studying the language, I was terrified of putting my language skills to such a tangible, transparent trial, subject to judgment and criticism. Well… all the more reason to give it a shot, right?

So I did. I tried translation for a while, and it went smoothly enough, but I realized I hated it. Most of the jobs I got made me feel like a machine. (Perhaps this was because I expected the kind of work I was doing to be replaced by a Google service in the near future, my hours of mental anguish reduced to the click of a button.) Still, there were things I enjoyed translating… bad subtitles, maybe, or an interesting name. But those are the kinds of translations I could only do strictly for fun.

These days I rarely stray too far from translation, because my academic work at ChinesePod is inherently tied to translation for pedagogical purposes. It really is a whole new game, and one whose challenges I find rewarding. Fortunately, translation nowadays is accomplished with a slew of digital tools, ranging from online dictionaries and databases to desktop reference tools (I’m looking at you, Wenlin!). It seems like the translator’s biggest headache these days is non-digital source text.

Despite all the technological advances, the issues a translator faces are, at their core, very human, and so human minds are obviously our best weapon for this task. What’s not obvious is where these translators are coming from. Proper translation from Chinese to English requires a native speaker of English, but the translators I meet aren’t typically the graduates of some kind of translation academy, and the translators out there now precede the new wave of China-focused graduates. They’re a mixed lot with completely different backgrounds, and they share a peculiar passion for translation that I certainly was never able to muster.

Translator Interview Series

This is why I did a series of interviews with translators in China that I know personally. I asked what I was curious about, and received a surprisingly diverse set of answers. Over the next five days I’ll be publishing one new interview every day. As I publish new interviews, the links will appear below, making this page an index for the series.

The interview lineup:

1. Brendan O’Kane (Bokane.org writer, freelance translator)

2. Peter Braden (ChinesePod translator and host)

3. Joel Martinsen (Danwei.org contributor/translator)

4. John Biesnecker (blogger, freelance translator, Qingxi Labs founder)

5. Ben Ross (barber shop anthropologist, translator/interpreter)

6. Megan Shank (blogger and freelance translator and journalist)

Specifically, I ask them about what kind of training/preparation they had to become translators, the role of technology in their trade, and the challenges and joys that translation work brings. Whether you aspire to become a translator, or you just have an interest in language, be sure to catch what these guys have to say on the topic.

[Apr. 8 Update: An interview with Megan Shank, originally planned for this interview, has been added to the lineup.]26

Mar 2009Beatles Songs with Chinese Characteristics

My coworker Pete has just started using Twitter under the name @pearltowerpete, and he’s begun a great series of Chinese puns involving Beatles song titles. Here’s what he’s got so far:

– Hey Zhu De

– The Long and Winding March

– So you say you want a Cultural Revolution

– Twist and Denounce

– Here Comes the Sun Yat-sen

More are sure to follow. Pete is ChinesePod‘s translator. (The funny hashtags (e.g. #cpod5) relate to ChinesePod’s new Activity Stream Twitter integration.)

24

Mar 2009English through Shanghainese

My coworkers Jason and Daini at EnglishPod have released a series of English lessons. But they’re taught not in English, not even in Mandarin, but in Shanghainese! They call it 上海话教英语.

If you’re interested in Shanghainese, this is better material than a radio show, because you’ll understand the English, which means you’ll be able to better follow the discussion of it in Shanghainese than you would a random topic.

Also, you might recognize the voice of one of the dialogue actors in this one:

Get the rest of them at 上海话教英语.

19

Mar 2009Korean Update

I while back I announced I was studying Korean, and since then I’ve had quite a few inquiries as to how it’s going. So let me make an official update: it’s not going. Yeah, that whole Korean study didn’t last too long.

Why not? Well, it turns out my reasons for studying Korean weren’t very good in the first place. A quick recap of why I decided to study Korean:

1. Korean looks cool.

2. Korean writing is phonetic.

3. I’ve already got a good foundation in 2 of 3 major East Asian languages down (might as well go for the East Asian Linguistic Trilogy).

4. It’s easy to do in China.

Just in case these reasons don’t strike you as entirely stupid, I’ll add a few incisive questions into the mix:

1. Do you need to learn Korean? Not at all.

2. Do you have plans to go to Korea? No, not really. Been there once, and it was nice, but I’m not itching to go back.

3. Do you have a love of Korean culture? TV dramas, maybe? No, not really.

4. Do you have many Korean friends that you could practice with? No.

5. Is learning Korean related to any other long-term goals you might have? No, not at all.

Hmmm, OK, I think that’s probably enough. So I basically had no compelling reason to learn Korean, and I gave it a shot anyway. It lasted 2-3 months, I learned a bit about the language, and it was fun. No regrets.

But I did learn a thing or two about motivation for language learning. Having a need or a use for the language you’re learning is important. This doesn’t mean that you should choose only super practical languages (Spanish, anyone?), but it does mean that trying to pick up a random language just because it’s kind of interesting probably won’t work. You need stronger motivation.

Aside from motivation, you need occasion to practice the new language. The opportunities for practice and the motivation for learning feed on each other. When you have both, they nurture each other. When you’re missing one, the other easily withers.

As it turns out, I had neither for Korean. I have both for Shanghai sign language, and it’s going really well. I’ll be writing more about that soon.

16

Mar 2009Learning Piano

In my recent post on learning in China, I mentioned that I started piano lessons this month. Some of my experiences illustrate nicely a few of the points I made in that post, so I’ll share them here.

A bit of background first. I studied piano just a little bit when I was in high school. I learned the basics of reading music, the notes of the piano keys, etc. Then, about 6 years ago in Hangzhou, I took piano lessons in exchange for English lessons for about half a year. So I’d say I’m still a beginner, but I’m not starting from scratch.

In my first two lessons I’ve taken quite a bit of criticism from my teacher. I don’t pay enough attention to my finger positioning or movements. My left hand accompaniment is not staccato enough, and my right hand isn’t playing the melody smoothly enough. (Who knew Oh Susannah could be so agonizing?)

So here’s how it works out for me linguistically:

Finger positioning. This requires little to no Chinese to learn. I’m hearing things like 不对 (“not right”) and 手指应该这样 (“the fingers should be like this”), all the while being shown the proper form, or, in some cases, having my fingers bent/moved for me. It may be difficult to conform to all the rules, but it’s certainly not hard to figure out what one is doing wrong, no matter the Chinese level.

Vocabulary. I’m hearing a lot of the same words over and over in my lessons: 节奏 (rhythm), 伴奏 (accompaniment), 断奏 (staccato), 连奏 (legato). Hmmm, do you see something these words have in common?

When I first started my lessons, I knew the word 节奏 (rhythm). The rest of the terms mentioned above all kind of made sense in context, and the second syllable zòu, which they all share, isn’t a very common one in Mandarin. So when it wasn’t entirely clear, I was still guessing that each word was somehow related to rhythm. Still, the frequency that those words came up drilled them into my head, and while possibly related, the terms clearly did not mean the same thing as rhythm. So I was compelled to look each one up when I got home, just to make sure I was understanding my teacher correctly. (You muddle through when you can, but once the repetitions reach a certain level, muddling starts to feel silly.) So I’ve already had those new additions to my vocabulary reinforced more strongly than any other words I’ve learned in a long time. This is learning.

Pedagogical background. The biggest difficulty we’re having communicating is that my teacher expects all her students to be familiar with the do re mi fa so la ti do technique for referring to notes in a scale (those in the know seem to call this solfège), but to me, that’s pretty much just just a song in The Sound of Music. I know the notes, and I’m fine with assigning numbers to them, but if you want me to play mi-mi-fa-re in the key of C right now, I’m lost. Fortunately, my teacher is accommodating and switches to names of the notes that I actually understand… when she remembers. I just give her that blank look every now and then to remind her.

My teacher doesn’t use English with me, but she mentioned that she has one or two foreign students with whom she has to use English. (This reinforces my point that speaking Chinese is not an absolute necessity for this stuff.)

Besides learning a few words, I’m starting to feel that I understand just a bit more of the pain of being a Chinese kid. Fortunately there’s still no Chinese mom making me practice piano when I’d rather go play.