13

Oct 2009Chinese Modal Verb Venn Diagram

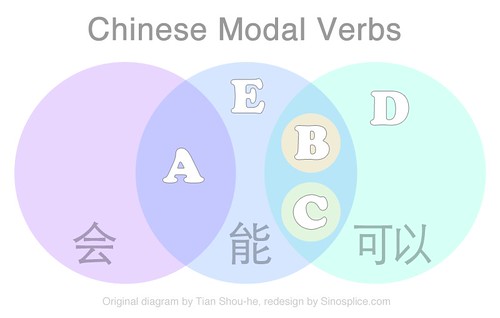

I’m a bit of a sucker for Venn diagrams. When I was recently asked by a student about the Chinese modal verbs 会, 能, and 可以 (all of which can be translated into English as “can”), I recalled a nice Venn diagram on the topic and dug it up.

What creates the most confusion with these three modal verbs is not that they can all be translated into “can” in English. The problem is that they are usually explained over-simplistically something like this:

> 会: know how to

> 能: be able to

> 可以: have permission to

This is not a bad start, but this sort of definition is eventually revealed as insufficient to the learner because in usage, the three modal verbs actually overlap. Enter the Venn diagram. The image below is a reconstruction of the one on page 95 of Tian Shou-he’s A Guide to Proper Usage of Spoken Chinese:

> A = ability in the sense of “know how to” (“会” is more common than “能“)

> B = permission/request (use “能” or “可以“)

> C = possibility (use “能” or “可以“)

> D = permission not granted (use “不可以“)

> E = impossibility (use “不能“)

Yeah, grammar needs more Venn diagrams.

Update: I’ve been informed that this diagram is actually a Euler Diagram. Oops. I stand corrected. I should have read up on the requirements for Venn Diagrams first! (Hey, some of those extensions are pretty cool!)

10

Oct 2009Chinese Telegraph Code

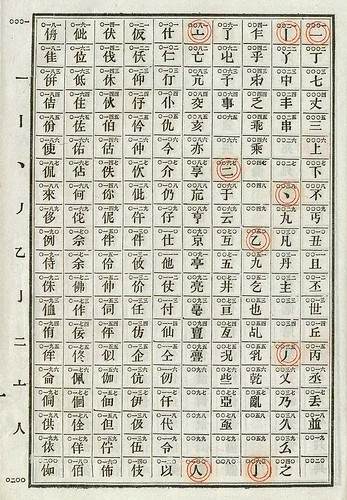

I wasn’t expecting to find anything Chinese-related on the new site, Easier to Understand than Wave (referring to Google’s new software, called Wave). But this was the first thing I got:

Chinese Telegraph Code

[Source: Wikimedia Commons]

Oh, and by the way, in this instance, Google Wave wins, 65% to 35%, making it part of an exclusive club of things harder to understand than Google Wave, which also includes “women, Scientology, the United States Tax code, Chinese telegraph code, Microsoft Visio 2004, and Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize.”

06

Oct 2009Slow Chinese

It’s the October holiday in the PRC, and I’m enjoying a slooowww 8-day vacation. Fittingly, I recently also discovered a site called Slow Chinese (via Chinese Forums), and thought I’d share it here.

Slow Chinese, as far as I know, is the first site to do this (and just this) for Chinese. I know that the same “slow” concept has already existed for some time for learners of German (Slow German), and that it is quite popular among that learner community. The idea, of course, is that if learners are exposed to enough slowed-down input, they will not only get better at recognizing the words they know, but will also be able to more easily pick out the words they don’t know, and the gains will gradually transfer to normal-speed input.

The linguistic question, of course, is: does this work? Is it a good idea?

First I’ll quote friend and fellow linguist JP Villanueva on what he once said about slow input:

> Listen to me: slow input does NOT help you learn language. No! NO NO NO. At best, slow input helps you learn SLOW LANGUAGE. […] Whenever you get mad at someone for “talking too fast,” you need to remind yourself that you don’t speak that language, and no amount of SLOW is going to help you understand.

> Counter-intuitive? Remember when you learned to ride a bike, and you found that it was easier to balance when you had a little speed? Remember when you first learned to drive, and you realized you had more control with a little speed?

> Same with language. Slow speech doesn’t help your memory. You don’t need every word in a sentence in sequence in order to understand what someone is saying.

> Besides, that’s not how your brain listens to your own native language, anyway. Your brain listens for semantic landmarks and then fills in the information in between. You need to learn to do that in your second language. Slow speech levels semantic landmarks, and over-emphasizes the non-content words that hold sentences together.

When it comes to Slow Chinese, there are actually two relevant questions:

1. Is slow input valuable?

2. Is slow input for news (or other media intended for native speakers) valuable?

In answer to question #1, I’d say yes. JP knows what he’s talking about, but earlier in the same post he also made a few caveats where confidence is concerned, and with good reason. There is a period when a beginner has a really tough time distinguishing the sounds of the target language. Yes, the purists are right when they say that continued, persistent exposure can overcome this obstacle, but most learners are not so hardcore. They’re emotional and easily discouraged. They want some help beyond “don’t give up,” and slowed-down input can provide that much-wanted crutch. It is a crutch, however, so if used, it should be withdrawn as soon as possible. It is most useful for learning the phonetics of the language as a beginner, in individual words and short phrases.

In answer to #2, I’d say no. If a learner is ready to take on media intended for native speakers, he should already be comfortable with the language at natural speed. If he has the vocabulary to take on the media but can’t handle the speed, it is likely because communication as a learning goal has been neglected. One can’t carry on normal conversation without comprehension of speech at a normal rate (unless one limits one’s conversation partners to slow-talkers only). So it seems to me that one would be tackling slow-speed media instead of tackling normal-speed listening comprehension and communication, which under most circumstances is a big mistake.

So my conclusion is that the learner’s time would best be spent working on simpler normal-speed input to improve listening comprehension (for Chinese, most Elementary and Intermediate ChinesePod dialogues are good for this; users can listen to the dialogue-only audio, all of which also have transcripts), and then later tackling normal-speed media.

Still, enthusiasm for learning is a valuable thing, so if Slow Chinese is what you’ve always wanted, I say go for it. (Plus, it’s free!) Just don’t forget that it’s not likely to help you out with conversational fluency, if that’s your goal.

29

Sep 2009Can't Afford

Intermediate students of Chinese will be familiar with the following pattern:

> V + 不起 = can’t afford to V

> V + 得起 = can afford to V

This pattern is most commonly about money, the typical example being 买不起 (can’t afford to buy).

The pattern is fairly productive, so you’ll see it for lots of different verbs (and not always about money), but recently I heard a new one. A friend was saying that she was going to eat at an expensive restaurant, but someone else was getting the bill. She said she ordinarily wouldn’t be able to afford even just her own meal at that restaurant (in China, each person getting her own check is a “system” called AA制), so in this case, she used: AA不起.

Heard any interesting usages lately?

24

Sep 2009Two Perplexing Photos

I was delighted to discover churros in Beijing, and with ice cream! (Sure, why not?) But the second English name threw me for a loop: “Kyrgyzstan Things Fruit.”

I don’t know why “churros” wasn’t enough, but apparently this is another casualty of horrible character-by-character machine translation. So we have a case of:

> Foreign word → Chinese transliteration → horrible machine translation to English

> churros → 吉事果 → “Kyrgyzstan Things Fruit”

Why go all the way to machine translation when you started with a foreign word in the first place? Did someone think that the machine translation of a transliteration might help out English speakers? Why is Kyrgyzstan the default translation for 吉?? There are no answers here… moving on.

I thought this was a rather clever bit of signage:

In context, and especially next to its “opposite” icon, there’s absolutely no question what the above icon stands for. Out of context, though, it can be a bit puzzling. I showed this to a few Chinese friends (out of context, of course), and they didn’t get it on their own.

(Hint: No, it has nothing to do with any characters in WALL-E.)

22

Sep 2009Three Tales of Two Cities

During our recent trip to Beijing, conversation naturally turned to comparisons of Shanghai and Beijing. I don’t want to rehash that tired topic (again) here, but there were three particular anecdotes told by Chinese friends which I found amusing. All involved interactions with the locals in which the storytellers’ values clashed with the locals’.

I’ve recreated them below, in spirit, at least, and translated them to English, but I’m not revealing the cities. See if you can identify the city from the story.

Anecdote #1

> I wanted to take the bus to the nearest supermarket, so I asked a middle-aged person on the street. The conversation went something like this:

> Me: Excuse me, which bus can I take to the supermarket?

> Man: Bus? What do you want to take a bus for? It’s not that far, and you’re young! Just walk. The weather is great. Go straight up that way 5 blocks, then turn left.

> Me: Thanks, but I’d like to take a bus, so…

> Man: I’m telling you, it’s a great walk! You don’t need a bus! Just walk up that way 5 blocks…

> Etc.

Anecdote #2

> I wanted to buy a bottle of water in a small store.

> Me: I’ll just take this bottle of water. All I have is a 50.

> Shopkeeper: I can’t change a 50.

> Me: Well, I don’t have change, so…

> Shopkeeper: I told you, I can’t change a 50. Come back when you have change.

Anecdote #3

> I needed to buy a lighter, so I sought out a nearby convenience store.

> Me: I’d like to buy a lighter, please.

> Cashier: A lighter? You don’t want to buy that here.

> Me: What do you mean?

> Cashier: Lighters are way cheaper at the shop down the street. You save 2 RMB!

> Me: Thanks, but I’d like to just buy one here, so….

> Cashier: I’m telling you, they’re cheaper down the street! You don’t want to throw money away, do you??

> Etc.

Can you identify the cities?

20

Sep 2009Weekend in Beijing

Light posting lately… I just got back from a weekend in Beijing. No sightseeing, no business… just hanging out, taking it easy, and seeing a few friends. Got together with Pepe, Brendan, Joel, Syz, Dave Lancashire, Roddy, and David Moser. And also happened to bump into Rob of Black and White Cat.

My wife and I spent most of our time on Bei Luogu Xiang (北锣鼓巷) or Nan Luogu Xiang (南锣鼓巷). We stayed in a nice little 四合院 hotel in the area called 吉庆堂. Thanks to Brendan, we ended up at a bar called Amilal both nights, which was a pleasant 20-minute walk from our hotel.

We had a good time, and my Shanghainese wife is liking Beijing more every time we go.

15

Sep 2009Sa Dingding is interesting

You may have heard of Sa Dingding before. Shanghaiist wrote about her a long time ago, and fans of “world music” will have known about her for quite some time. As I understand it, she’s only recently been catching on in China in a big way, which is how I was introduced to her music by a Chinese friend.

From her Last.fm page:

> Sa Dingding is a singer and musician born in Inner Mongolia. She sings in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Lagu, and Mandarin, and also in a self-created language. She plays several instruments, including the zheng, the Chinese drum, Chinese gong, and horse-head fiddle. Inspirations include Buddhism and Dyana Yoga.

You can see why Sa Dingding is an artist that might appeal to linguists! Her unique style is a great example of Chinese creativity, as well.

Her most popular song is 《万物生》 (Alive in English). Here it is in Mandarin [Youku video]:

And here is 《万物生》 in Sanskrit:

If you’re in China, all of Sa Dingding’s music is available for free online from Google.cn music: 萨顶顶 (if only Google would properly ID3tag it!).

You’ll also note that most sources write Sa Dingding’s name as “Sa Ding Ding.” I find this interesting. You don’t write “Deng Xiao Ping” or “Zhang Zi Yi.” The surname is capitalized, and the given name is written as one word, also capitalized. Do people feel that a given name with a reduplicated character must be written so that each syllable is also exactly duplicated?

You can see the same tendency for Fan Bingbing (“Bing Bing”) and Li Bingbing (“Bing Bing”) as well, but the Wikipedia pages for those two actually follow the proper pinyin name-writing convention [see section 2.3]. (Perhaps the “Sa Ding Ding” page will be wiki-harmonized soon? [Update: It was changed within 24 hours! Wow!])

Her own website uses “Sa DingDing” in the HTML title, but “Sa Dingding” on the site pages themselves.

12

Sep 2009Pushing the Limits of Transracial Adoption

My sister Amy forwarded this thought-provoking article to me: Raising Katie: What adopting a white girl taught a black family about race in the Obama era.

In case it’s not immediately obvious, here’s the focal point of the piece:

> So-called transracial adoptions have surged since 1994, when the Multiethnic Placement Act reversed decades of outright racial matching by banning discrimination against adoptive families on the basis of race. But the growth has been all one-sided. The number of white families adopting outside their race is growing and is now in the thousands, while cases like Katie’s—of a black family adopting a nonblack child—remain frozen at near zero.

> Decades after the racial integration of offices, buses and water fountains, persistent double standards mean that African-American parents are still largely viewed with unease as caretakers of any children other than their own—or those they are paid to look after. As Yale historian Matthew Frye Jacobson has asked: “Why is it that in the United States, a white woman can have black children but a black woman cannot have white children?”

This article made me think back to the time I saw a big group of foreigners at the Shanghai Pudong airport, each couple carrying a precious newly adopted Chinese baby, getting ready to fly back home. I didn’t think anything of it at the time, but now I do realize that all of them were white.

So this does make me wonder… Would a black couple have trouble adopting a Chinese baby in China?

10

Sep 2009A Character-Counting Challenge

My recent post on the Wikimedia Commons Stroke Order Project prompted Mark of Toshuo.com to decry the relative dearth of traditional characters being added to the project. To this, David on Formosa reminded Mark that there are also a large number of characters shared by the traditional and simplified character sets.

At this point I’ll interject a visual aid (gotta love them Venn diagrams!):

All this got me thinking about the following question: If “s” represents the characters in the simplified set not shared with the traditional set, while “t” represents the characters in the traditional set not shared with the simplified set, and “u” represents the characters shared by the two sets, then what are the number of characters belonging to groups s, t, and u, respectively?

It seems like a simple enough question, but it’s actually quite tricky for a number of reasons.

First, the total number of Chinese characters in existence varies according to source, and largely depends on how many non-standard variants you want to include in your total set. You can be reasonably certain the total number is less than 50,000, but that’s still a pretty ridiculously large number, when most Chinese people regularly use less than 5000. For basic purposes of comparison, it makes sense to limit your set to a certain number of commonly used characters, but which set? One from the PRC? From Taiwan? From Hong Kong? From Unicode?

Second, you might be tempted to think that s = t, because simplified characters were “simplified from” traditional characters. This isn’t true, however, because in many cases multiple traditional forms were conflated into one simplified form. To give a very common example, traditional characters 干, 幹, and 乾 are all written 干 in simplified. So adding these three characters adds 1 to u, 2 to t, and 0 to s. There are lots of similar cases, so clearly t is going to be significantly larger than s. But by how many characters?

I’d be very interested to see a concrete answer to this question, regardless of the character limit used. I also wonder how the proportions of s, t, and u vary as the character limit is increased, and more and more low-frequency characters are included.

If you’ve got an answer, I’d love to hear from you!

08

Sep 2009Fuzzy Pinyin

This is a screenshot from the Google Pinyin installer:

If you’re learning Mandarin for real, sooner or later you’re going to need to experience the rich variety in pronunciation that Greater China has to offer. This simple “fuzzy pinyin” options screen gives you an idea of what’s out there. (Speakers that can’t differentiate between z/zh, r/l, f/h, etc. typically can’t properly type the pinyin for the words that contain those sounds in standard Mandarin, so fuzzy pinyin input saves them a lot of frustration.)

03

Sep 2009The Wikimedia Commons Stroke Order Project

If you’ve checked out many online Chinese dictionaries or websites on learning Chinese, you’ve seen a variety of ways to present characters’ proper stroke order. Animated GIFs are a favorite, but they often fall flat in one important respect: they display each stroke in a single frame, often leaving the direction of the stroke somewhat unclear.

This is where the Wikimedia Commons Stroke Order Project impresses me: not only are the animated GIFs large and attractive, but they fluidly demonstrate the direction of each stroke. A nice example:

More info from the site:

> Hello, and welcome to the Commons Stroke Order Project. This project aims to create a complete set of high quality and free illustrations to clearly show the stroke order of East Asian characters (hanzi, kanji, kana, hantu, and hanja). The project was started as there was none like it in terms of quality and it seems that it is the only one working on all three schools of Han character stroke order; simplified and traditional Chinese, and Japanese.

> You are free to use the graphics we’ve made and welcomed to join us and contribute to our progress. It’s easy, you just have to follow the simple steps stated in our graphics guidelines.

At 378 total characters, the project is still far from a complete set, but it’s off to a nice start!

I do, wonder, though, what kind of stroke order information is freely available out there that could speed the process along. I’ve seen enough separate sets of animated characters to make me suspect many have been automatically generated. (Anyone have info on this?) I’m also curious how the project is going to deal with the annoying issue of variable stroke orders.

Note that there is also an Ancient Chinese Characters sister project.

29

Aug 2009Chaintweeting over the GFW to Twitter

We live in a world of fascinating, interactive web services, but unfortunately, those of us in China are cut off from some of the leading websites. Most conspicuous among these are YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook. None of these websites are currently accessible in China, cut off by the Great Firewall (GFW) of China. Twitter and Facebook, most notably, have APIs, which enable other software, web services, and mobile phone apps to connect to and interact with them. But since all of these uses of the API make direct calls to Twitter or Facebook’s servers, none of these work in China either.

Working with Reign Design recently on OpenLanguage, I happened to browse Reign Design’s blog and came across this entry: Posting to Twitter via SMS in China. This interested me because I used to enjoy the convenience of posting to Twitter via SMS, and it’s a way to circumvent the GFW. I stopped because Twitter quit offering local numbers, and international SMSes are a bit expensive just for a tweet.

Anyway, I read the article, and the PHP script looked simple enough, so I headed over to Fanfou, where I already had a seldom-used account. I was surprised to discover, though, that Fanfou is gone. Nothing but a smoking crater where there used to be a lively community. Considering some recent events in China and the immediate, individual-empowering nature of microblogging, it’s not hard to imagine what happened.

With that option closed to me, I decided to check out the other big Chinese microblogging service I was familiar with, Zuosa (做啥). I really liked Zuosa, where I found a lot of advanced features that even Twitter has held back on. Then I went into settings, where I saw the familiar Twitter “t” next to the 同步到微博客 (“Sync to microblogs”) section.

When I clicked on that section, and then on the Twitter “t,” I got this message:

The message says:

> 抱歉,该服务不可用;你可以通过 zuosa->buboo.tw->twitter 实现同步!

Translation:

> We’re sorry, this service is not available. You can go through zuosa -> buboo.tw -> twitter to accomplish the sync!

So I set up an account on Buboo.tw (ah, traditional characters!), easily synced that with Twitter, then synced my Zuosa account with Buboo. And hey… it works (1, 2, 3)! A tweet on Zuosa appears on Twitter in seconds. And since I synced my Twitter account to Facebook long ago, Facebook is actually at the end of the tweetchain: Zuosa -> Buboo.tw -> Twitter -> Facebook.

I haven’t tested SMS tweeting yet. One of the disadvantages of this method is that you can’t not post “downstream.” So for now, I can’t post only to Zuosa without posting to the other three, or post to Buboo without posting to Twitter and Facebook, unless I turn off the sync.

Anyway, I thought this was pretty cool… all made possible through international open APIs.

27

Aug 2009Google Pinyin for the HTC Hero

I got the Google Pinyin input working for my HTC Hero Android phone. It turned out to be quite simple. The only two things holding me back were (1) a bad install of Google Pinyin, and (2) lack of proper documentation for switching input methods.

When I first got the phone, it already had Google Pinyin installed, but apparently it was an old version that didn’t work properly. I had to uninstall it and reinstall it. To uninstall, go to: Settings > Applications > Manage Applications, and uninstall it from there. The applications may take a while to all load, but Google Pinyin, if installed, should be at the very bottom, listed by its Chinese name, 谷歌拼音输入法. Select it to uninstall it.

After you’ve got the latest version of Google Pinyin from the Android market installed, go to Settings > Locale & text, and make sure that you have Google Pinyin activated. (I turned off Touch Input Chinese because it didn’t seem to work.)

From the menu above, you can also turn on predictive input (联想输入, literally, “associative input”) and sync (同步) your custom words with your Google account. (For some reason this is not automatically synced like the rest of your Google account services are.)

One you’ve got Google Pinyin installed and turned on, you’re ready to type something. For my demo, I went into my SMS messages and opened up one of the recent ones from China Merchant Bank. To switch input modes, you tap and hold the textbox. A menu will pop up, and you choose “Select input method.” Then choose “谷歌拼音输入法.”

Now you’ve got the Google Pinyin soft keyboard. Start typing, and characters will appear. As you can see from my example below, it’s not perfect, but it’s pretty good most of the time. You also have an extra keyboard of symbols in addition to punctuation, which is nice.

I have to say, it’s a bit annoying to have to go through a three-step process every time to change the input method. I could do it with one keypress on the iPhone, but that’s only if I have only one alternate input method installed. As Brendan has pointed out, it could be quite a few extra keypresses depending on how many input methods you have installed. For the time being, on the Hero, it’s always three keypresses.

Anyway, hopefully this helps a few other people figure out how to get Google Pinyin working on an HTC Hero.

25

Aug 2009The Tyranny of the Textbook

Lately I’ve been working with Nick Kruse of Reign Design on a new project at work called OpenLanguage. Much of our discussion has centered on teachers and students, and the language-learning experience in general.

Nick related to me a story about taking the very limited Chinese he had learned in the classroom back in the States, and then traveling to China and applying it extensively. He discovered that some of the language they learned from Practical Chinese Reader, besides being outdated, was, well… not so practical.

Specifically, when Chinese people encouraged him over and over with the same sentence — “你中文讲得很棒!” (“you speak great Chinese!”) — he didn’t understand what they were saying because he hadn’t learned two of the key words.

When he got back to the States, he had a conversation with his Chinese teacher that went something like this:

> Why didn’t you teach us 讲 [speak] and 棒 [great]?

> It wasn’t in the book.

> But those are useful words!

> We have to follow the book.

I’m happy to see the overall attitude toward language learning changing, and I’m even happier to be a small part of that change.

22

Aug 2009Buying the HTC Hero in Shanghai

Photo by louisvolant

On Thursday I went with coworkers Hank and Jenny to get an HTC Hero. Jenny’s Taobao research had revealed lots of vendors advertising the new Google Android smartphone, but with fluctuating prices and changes in stock. (The phone has not officially hit the Chinese market yet, so these are all unofficial imports, or 水货 in Chinese.) Anyway, we finally settled on a vendor near Shanghai Train Station.

When we found the shop on the sixth floor, Jenny also noticed that there were other shops selling the phone at competitive prices. We stuck to our original guy, though. His price was 3800 RMB, without SD card or GPS software installed. He was selling all sizes of SD cards, recommending the 8 GB one for 200 RMB. Hank and I both wanted the 16 GB card, which sold for 360 RMB. It was kind of funny… the vendor tried to talk us out of it, saying everyone gets 8 GB, and there’s no need for more than that. We both got the 16 GB (partly, I suspect, because we both had 8 GB iPhones).

Language Issues

The phone was evidently imported from Eastern Europe. The “Locale and Text” options included options like “Čeština (Česká republika)” and “Polski (Polska)” and “Polski (Węgry)”. The most appealing options for me, as an English speaker, were “English (Romania),” “English (Slovakia),” and the like.

The interface of the HTC Hero, when presented by the vendor, was entirely in Chinese. It looked great, but I wanted to try the smartphone out in English first, so I went to the “Locale and Text” setting and chose “English (Poland).” What I didn’t notice at the time was that Chinese was not an option in that menu. Once I changed away from Chinese, I couldn’t change back! In addition, once out of Chinese interface mode, you don’t have access to Chinese input. You can install Google Pinyin IME on the phone (awesome!), but there’s no way to actually access it when you type because it doesn’t appear in the input select menu like you’d expect.

This is a short-term issue; the phone clearly does have built-in support for Asian languages, and HTC is a Taiwanese company, after all. For now, I can receive Chinese SMS text messages just fine, I just can’t write them. I’m confident I can resolve this issue, either with or without the vendor’s help, but it’s one of the hassles of a buying a version of a product that wasn’t meant for your region and its special needs. Chinese vendors will likely solve this problem soon, but the Hero is still a very new arrival.

When I figure out how to add Chinese input to the Hero (and it’s gotta be Google Pinyin input!), I’ll post an update. [Update: I have figured it out and written a blog post called Google Pinyin for the HTC Hero.]

20

Aug 2009Jokes from Jiong.ws

My wife recently introduced me to the humor site 一日一囧 (Jiong.ws). The videos she showed me were crude animations, each telling a single simple joke. Some were unfunny, some were Chinese translations of jokes I’d heard before, but a few very funny and worth sharing.

Of the four clips below, the first three are linguistic in nature. You’re going to need at least an intermediate level of Chinese to understand these jokes. I’ve provided a transcript for the last one, which has a lot of narration but no subtitles.

1. 太阳打电话 (The Sun Makes a Phone Call)

Priceless! This joke revolves around the words 草 (grass) and 日 (sun), and how they sound like the obscene 操 and 日 (same character and pronunciation, different usage). The funny accents make the joke work well. Of course, some experience in “overheard phone calls” in China also helps.

18

Aug 2009Learning Your Way to Yourself

The acquisition of any foreign language comes with struggle. Not just the burden of memorizing a new lexicon or the labor of demystifying an unfamiliar syntax, but the struggle of making oneself understood in the target language. It’s not easy!

Naturally, many mis-communications are committed as fluency is built upon a mountain of mistakes and micro-lessons learned. Language learners are not robots (yet!), however… they desire not only to communicate information, but to express themselves. They want to show their personalities, to be themselves in the target language.

Orlando Kelm, teacher of Spanish and Portuguese, observes:

My experience is that it just kills some people to not be able to say something in a foreign language without the same intensity, passion, and flowering language as in their native language. If they can’t say it like they would in their own language, they end up not saying anything at all. Other people are OK with their more limited, simple, and brief non-native version. Basically, if you are not willing to go with the simplified version, you’ll have more difficulties in speaking the foreign language. With time and practice your simple version will develop, but not if you aren’t willing to start with whatever you can pull out of your brain in the initial phases.

Although I have nowhere near Dr. Kelm’s years of experience with language learning, I, too, have witnessed this phenomenon in many learners, and I’ve had to deal with it myself. To make matters worse, I’m not a terribly outgoing person, and I’m not a fan of small talk. These qualities are not conducive to practice in the target language!

It may be that this problem is most pronounced for those with a very strong identity. Someone who is always the life of the party may have a really hard time being that guy that’s hard to understand and that doesn’t make much sense. The quick-witted jokesters may find it especially painful to never be funny in the target language (for a very long time). These learners may feel if they can’t be themselves to the people they meet, they’d rather not meet those people.

For me, my identity didn’t get in the way so much. I enjoyed the challenge of communication in Chinese, as humbling as it was. I repeatedly put myself in situations where I needed to talk, and then I would just say anything I could think of to say. This comes naturally to the outgoing, talkative types, the people that hate silence. For some of us, though, it’s incredibly difficult! With this approach, you rarely end up talking about what you really feel like talking about (largely because everything is dumbed down to your language ability), but you actually end up talking, most of the time, which is exactly what you need as a new learner.

Essentially, what I did amounted to changing my personality in the target language. I became someone who frequently started conversations with strangers, someone who asked questions which sometimes were none of my business, someone who would keep small talk going indefinitely.

Over time, I found it easier and easier to express myself in Chinese. I could even start making simple jokes. My efforts were working, but I realized that I had donned this alter-ego which placed me in a certain developmental trajectory. It was one which, as far as I could tell, could only be fully realized by someone totally unlike me. Maybe working at becoming a brilliant story-teller, or public speaker, or comedian (xiangsheng?) — in Chinese — would be the best thing possible for my language abilities, but I realized that that just wasn’t me. As my identity reasserted itself, I began acting more like myself, but also more like a native speaker in some ways, because I had lost my sociable fearlessness.

This is a good problem to have, though, because you have choices. If you’re still struggling in those early stages, you’re faced with one fundamental choice over and over again: to talk or not to talk. For this scenario, Dr. Kelm’s advice is as good as it gets:

Next time you are part of that beautiful sunset, turn to the person next to you and tell him/her what is in your heart, even if the actual words are just “sunset good.”

16

Aug 2009Physalis: Another Weird Fruit in China

One of the things I love about living in China is that I just keep on discovering bizarre things. I thought I had already seen pretty much all the “alien” fruits China had to offer, and then recently a co-worker brought some “姑娘” back from China’s northeast. Apparently these are called physalis in English. (How did I miss them all this time??) Anyway, bizarre, and kinda good!

From Wikipedia on physalis:

> The typical Physalis fruit is similar to a firm tomato (in texture), and like strawberries or other fruit in flavor; they have a mild, refreshing acidity. The flavor of the Cape Gooseberry (P. peruviana) is a unique tomato/pineapple-like blend. Physalis fruit have around 53 kcal for 100 grams[2] , and are rich in cryptoxanthin.

Here are some photos from Flickr, all taken by their respective owners:

Unfortunately, none of the photos I was able to find on Flickr included a picture of what the inside of the fruit looks like. I attempted a photo at night with my iPhone, and it didn’t turn out great, but you get the basic idea:

The seeds kind of reminded me of green pepper seeds, but smaller. Here’s a Chinese article with more pictures and info in Chinese.

15

Aug 2009Unaccustomed Earth

Today I was reading Unaccustomed Earth, a collection of stories which owes its title to this great quote from Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Custom-House:

> Human nature will not flourish, any more than a potato, if it be planted and replanted, for too long a series of generations, in the same worn-out soil. My children have had other birthplaces, and, so far as their fortunes may be within my control, shall strike their roots into unaccustomed earth.

Well put.