18

Mar 2010Chinese Characters Spliced into English Text

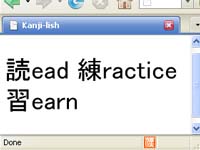

There’s a Firefox add-on called Characterizer (originally Kanjilish, for Japanese) which replaces parts of words with Chinese characters. My initial reaction was that it was just gimmick without much real value, but I’m starting to wonder.

In the screenshot above, the characters are for Japanese; for simplified Chinese they would probably appear as:

> 读ead 练ractice 学earn

Unfortunately the add-on only works for older versions of Firefox, so I can’t try it out. The concept, as stated by the author, is:

> As a busy professional, I don’t always have time to practice Japanese as much as I like. I developed this add-on so that I could keep kanji characters fresh in my mind, even when I wasn’t reading Japanese.

So the idea is to semi-passively reinforce characters already learned. Makes sense.

One part that intrigues me about the add-on, though, is the missing letter. Every time your brain encounters a word with its first letter replaced by a Chinese character, for just that split second, it kind of freaks out, but then recovers gracefully. I feel that my brain, however, is definitely focused on decoding the proper English word, treating the mildly horrific character-letter hybrid as a sort of captchaesque nuisance blocking its way to comprehension. The characters are just mentally swept away by this process.

Actually, I find the whole mental process very much like the now-famous message below:

> Aoccdrnig to rscheearch at Cmabrigde uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteres are at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a tatol mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit a porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae we do not raed ervey lteter by it slef but the wrod as a wlohe.

What I really wonder, though, is: what effect would prolonged exposure to character-letter hybrids have on someone who has never studied the characters? Would they eventually start to form associations between words and characters?

The process needn’t be exactly like Characterizer does it. Here’s an alternate example by syllable:

– 北ei京ing

– 上hang海ai

– 香ong港ong

– 台ai湾an

– 西i安n

– 杭ang州hou

The longer ones definitely seem to work better. If you don’t read Chinese, how many of the place names above can you read?

Here’s another list (version 1):

– 姚ao 明ing

– 章hang 子i怡i

– 巩ong 俐i

– 张hang 艺i谋ou

– 葛e 优ou

– 周hou 立i波o

– 大a 山han

– 毛ao 向iang辉ui

Same list (version 2):

– 姚ao Ming

– 章hang Ziyi

– 巩ong Li

– 张hang Yimou

– 葛e You

– 周hou Libo

– 大a Shan

– 毛ao Xianghui

How did you fare in the two lists above? Was version 1 a lot harder? How about 2- versus 3-character names? The names are roughly in “fame order.” Did it get harder as you went along?

You could take the concept in a lot of directions. Definitely worth exploring some more.

15

Mar 2010Chinese Radio on the Internet: a Platform-Agnostic Option at Last!

In theory, watching Chinese TV seems like a great way to expose oneself to more Mandarin. But somehow I can’t bear to watch most TV programs in China. It’s not that I’m immune to the charms of all forms of Chinese media, though. Strangely, I’ve found that I tend to encounter the most interesting Chinese programs while riding in a taxi late at night. It’s those call-in advice radio shows that taxi drivers like so much. I love those shows!

What’s so great about the call-in shows? Here are some of the reasons I like them:

1. They don’t come across as rehearsed, and if they’re not 100% real, the interactions sure seem spontaneous to me.

2. The callers are from all over China, so there’s a great variety of accents.

3. The language (of the callers, at least) is unpretentious and real.

4. As callers discuss their personal problems, you get some nice snapshots of various Chinese social issues.

5. Many of them are actually very easy to follow; tuning in feels like much less of a listening comprehension exercise than other programs.

Naturally, I don’t want to actually listen to these shows on the radio at their scheduled times, I want to listen to them online when I want to listen to them. So quite a while ago I started hunting for ways to tune into Chinese radio stations online. There are more than a few, but there are serious inconveniences associated with each. The types of shows I wanted were hard to find, and most stations required either Windows Media Player, IE6, or RealPlayer. No good!

Recently, however, I discovered a Chinese website that has gotten it right. It’s radio.BBTV.cn, 上海网络广播电台 (Shanghai Internet Broadcasting Station), an effort of SMG. So what’s so great about this site? Allow me to gush a bit…

12

Mar 2010The Value of a Master’s in Chinese Economics

In a recent post entitled Why China for Grad School? I opined:

Aside from reduced cost, there is one main reason a westerner might choose to go to grad school in China over a western country: because one’s object of study is inherently Chinese. This includes Chinese history, Chinese art, Chinese language, etc.

There are definitely foreigners in Shanghai that have elected to earn their advanced degrees in China, but in fields other than those mentioned above. Curious about how they see their education, I’ve decided to interview a few. The following is an interview with American Zachary Franklin, a writer who also maintains the blog Writer’s Block on his website, DeluxZilla.

John: Can you tell me what graduate degree you’re working on?

Zachary: I am currently a first-year master’s student working toward an M.A. in Chinese Economics from Fudan University, a two year degree program taught through the School of Economics.

John: So what kind of program is it? Is it meant for foreigners, or is it all Chinese?

Zachary: It is an English-taught, M.A. program, focusing on both economics and the Chinese economy in the context of the past 30 years of development and where the Chinese economy is heading in the coming decades.

It is meant for foreigners. My class has 15 other students from around the world, including countries such as Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, Hungary, Norway, Italy and the United States. This specific degree program has been around since 2006.

The difference between myself and the other 15 students is they are taking the degree completely in English, whereas I am taking half the degree in Chinese.

Both Fudan University and the Economics School have been extremely supportive and encouraging in allowing me to split my degree. What ends up happening is I take core economics classes — microeconomics, macroeconomics and econometrics — in English, learning theory and mathematical formulas, while getting to take more discussion-oriented classes in Mandarin. Last semester I took “World Economies” in Chinese, and this semester I am taking both “Regional Economics,” which focuses on why Chinese provinces have developed the way they have over the past 15 years, and “Chinese Dynastic Economic Thought.”

John: I mentioned in a recent blog post that I thought it mostly only makes sense to earn a graduate degree in China if the subject matter is inherently Chinese. I guess you would take issue with that statement?

Zachary: I don’t take issue with your statement so much as it is going to be a moot point. The invasion is coming. In the next 10 years there will be masses of foreigners from all corners of the globe coming to China to study in universities, in numbers far greater than what China has seen previously. In the United States alone, President Barack Obama said back in Nov. 2009 he wants to send 100,000 American students to study in China over the next four years. Even if you feel universities here need to change their methods and improve their standards, it won’t matter. The increased demand will naturally change the system. It has to.

Will foreigners be coming to China to study subjects such as Russian literature or peace and conflict studies in the Middle East? I don’t know, but it seems there are already several other universities around the world that have those programs and are more well-known for those degrees.

Instead, what we’re going to see is many coming to China to learn the language, but many more who already have a very accomplished level of Mandarin. To cope with increased overall demand, universities around China will have to adapt to handling a higher percentage of foreigners. They’re going to have to meet demands, change standards where necessary and offer a more diverse curriculum.

John: You almost make it sound as if the subject matter is only secondary, and the important thing is getting in with the Chinese before “the invasion.”

Zachary: Of course the subject matter is important, but as I am in China and studying economics, it is important to take stock in the economic changes happening all around and apply what I’ve learned in the classroom accordingly.

So, in terms of value, how do you see your M.A. in Economics from Fudan?

Zachary: I see an M.A. in Chinese economics from Fudan University to be three degrees — though I am certain I will only receive one of them from the school.

There is the obvious, the economics degree. There is also what I feel will be my completion of Mandarin. I spent 18 months in Beijing before coming to Fudan, reading, writing and speaking Chinese six hours a day, five days a week, in an intense program at a private language institution. Trying to earn a master’s degree utilizing my Mandarin was simply the next logical step.

The last degree is the least obvious, but nonetheless one that is of great importance. I feel my time as a student at a Chinese university allows me to understand the educational system in this country. For the majority of Chinese students graduating, what they study at school goes to the industry where they will eventually begin work. Understanding why they’ve chosen a particular major to continue their education, what their classroom activities are doing to prepare them for the real world, where they hope to see themselves in five or 10 years; all this contributes to understanding the people around. And 10 years from now, who knows where my former classmates will be and what field they will be working in.

John: How do you see your M.A. in Economics from Fudan compared to one you might get from an American university? What are the trade-offs?

Zachary: Economics is economics regardless of where one is studying. There are core principles everyone is taught and everyone understands. The differences come when one considers where I am located and the language I am using to obtain my degree.

I am studying economics in China, and I’m using another language for part of the degree. Physically being here is priceless in terms of the perspective I am being exposed to. You cannot compare studying economics in Shanghai — with so much going on around — and studying economics 9,000 miles away in the United States. I step out my front door every morning and see everything Americans can only read about in the New York Times. In my mind, there are no trade-offs when you think about it like that.

You can follow Zachary’s progress in his M.A. on Writer’s Block.

09

Mar 2010Project A Update

I recently asked my readers to email me if they were interested in participating in a project focused on learning Chinese in Shanghai. The response was quite good, and I’d like to thank all of you that generously offered to participate.

I’m actually a bit reluctant to deactivate the email address, because the responses are still trickling in. Some of the details of the project are taking longer than expected to crystallize, however, so it’s not yet time to start. You’ll be hearing from me soon.

This means that there’s still time to email me if you’d like to participate. Once again, the project will start with an online survey, then will happen later this month (or possibly early April) at a physical location in Shanghai. (So yes, you must be in Shanghai to participate.)

Here’s the email address again:

Thanks, everyone, for your support! I’ll be posting future updates when the time comes.

07

Mar 2010The Singularity and the Chinese History of Chess

While reading up on one of my favorite topics, the technological singularity, I recently came across this interesting passage in an article by renowned futurist Ray Kurzweil entitled The Law of Accelerating Returns:

> To appreciate the nature and significance of the coming “singularity,” it is important to ponder the nature of exponential growth. Toward this end, I am fond of telling the tale of the inventor of chess and his patron, the emperor of China. In response to the emperor’s offer of a reward for his new beloved game, the inventor asked for a single grain of rice on the first square, two on the second square, four on the third, and so on. The Emperor quickly granted this seemingly benign and humble request. One version of the story has the emperor going bankrupt as the 63 doublings ultimately totaled 18 million trillion grains of rice. At ten grains of rice per square inch, this requires rice fields covering twice the surface area of the Earth, oceans included. Another version of the story has the inventor losing his head.

> It should be pointed out that as the emperor and the inventor went through the first half of the chess board, things were fairly uneventful. The inventor was given spoonfuls of rice, then bowls of rice, then barrels. By the end of the first half of the chess board, the inventor had accumulated one large field’s worth (4 billion grains), and the emperor did start to take notice. It was as they progressed through the second half of the chessboard that the situation quickly deteriorated. Incidentally, with regard to the doublings of computation, that’s about where we stand now–there have been slightly more than 32 doublings of performance since the first programmable computers were invented during World War II.

> This is the nature of exponential growth. Although technology grows in the exponential domain, we humans live in a linear world. So technological trends are not noticed as small levels of technological power are doubled. Then seemingly out of nowhere, a technology explodes into view. For example, when the Internet went from 20,000 to 80,000 nodes over a two year period during the 1980s, this progress remained hidden from the general public. A decade later, when it went from 20 million to 80 million nodes in the same amount of time, the impact was rather conspicuous.

I’d never heard the claim that the Chinese invented chess; I’ve always heard that the game was invented by the Indians or Persians and then later iterated by the Chinese. Kurzweil’s story also seems a bit suspect to me because of its reference to “squares,” which does not match the forms of Chinese chess I’m familiar with, but then again I’m no expert on any kind of chess. Wikipedia has this information on the history of chess in China:

> Joseph Needham posits that “image-chess,” a recreational game associated with divination, was developed in China and transmitted to India, where it evolved into the form of modern military chess. Needham notes that dice were transmitted to China from India, and were used in the game of “image-chess.”

> Another alternative theory contends that chess arose from Xiangqi or a predecessor thereof, existing in China since the 2nd century BC. David H. Li, a retired accountant, professor of accounting and translator of ancient Chinese texts, hypothesizes that general Han Xin drew on the earlier game of Liubo to develop an early form of Chinese chess in the winter of 204–203 BC. The German chess historian Peter Banaschak, however, points out that Li’s main hypothesis “is based on virtually nothing”. He notes that the “Xuanguai lu,” authored by the Tang Dynasty minister Niu Sengru (779–847), remains the first real source on the Chinese chess variant xiangqi.

In my half-assed 5-minute Wikipedia/Baidu Zhidao research, I don’t see reference to the emperor of China sponsoring the invention of any form of chess. Could this be an inaccurate reference to Han Xin (韩信), who is connected to the history of Chinese chess (象棋)? If anyone has more info, I’d love to hear it. Is Kurzweil’s story about Chinese chess, rice grains, and exponential growth just another fake Chinese anecdote, or is there anything to back it up?

04

Mar 2010Creative English with Chinese Characteristics

Just in case you missed these English language Chinese coinages, here’s a sample:

> Smilence 笑而不语

> vi. When you are expecting some answers from your Chinese audience, you may just get a mysterious smile and their silence only.

> 动词 当你期望从中国听众那里获得一些回答的时候,你只得到了神秘的微笑和他们的沉默。

The rest of the list is here, but here’s a taste of what you’ll find:

– Democrazy

– Togayther

– Freedamn

– Shitizen

– Divoice

– Animale

– Amerryca

– Innernet

– Yakshit

– Departyment

– Suihide

– Don’train

– Corpspend

– Jokarlist

– Vegeteal

– Sexretary

– Canclensor

– Carass

– Harmany

Smilence is definitely the best one. It’s interesting how some of them don’t work very well from the perspective of a native speaker of English, while others are pure gold.

Via China Digital Times.

02

Mar 2010Chinese New Year Line Dance

Overheard near Jing’an Temple, a conversation between a Chinese woman and an American woman:

> Chinese woman: It is Chinese New Year, time for line dance.

> American woman: Really, line dances? You do line dances for Chinese New Year?

> Chinese woman: Yes, line dance.

> American woman: What kind of line dance?

> Chinese woman: You know, Chinese line. Like that stone line.

> American woman: Oh, lion dance! OK, I see.

I don’t mean to make fun of anyone’s pronunciation, but the idea of a “Chinese New Year Line Dance” was just too good. (Maybe for next year’s craptacular?)

25

Feb 2010Experiments in Learning Chinese in Shanghai

Working on lesson content at ChinesePod keeps me busy as always, but recently I’ve also started a project on the side. While ChinesePod is great for distributing excellent lesson content to an unlimited audience, I’m also very interested in individual learner experiences in Shanghai.

There are so many fascinating linguistic dramas going on here… crises of confidence, language “power struggles,” accent ambushes, tone trip-ups, etc. I also think that, for many reasons, it’s especially difficult to learn Chinese in Shanghai. I’d like to study these phenomena, up close and in detail.

If you’re interested in participating in my project, please email me here:

The project will begin with a survey, but will later include real-life Chinese practice (for research). I’m particularly interested in learners from the elementary to intermediate range.

I will deactivate the above email address after several weeks, so please email me soon if you’d like to help. Thanks a lot!

Update: Thanks for all the emails so far! I’ll be replying to you all soon.

23

Feb 2010Why China for Grad School?

I chose to earn my master’s in applied linguistics here in Shanghai, through a Chinese-language program at East China Normal University (华东师范大学). While I’m certainly not the only foreigner to ever do this, I get a lot of inquiries about it, as more and more non-Chinese focus on China. Although I’ve written a bit about different aspects of grad school in China in the past, I find it difficult to offer a very useful comparison simply because I’ve never attended any graduate courses in my home country of the United States; I’ve only ever done it in China. Still, I’d like to share some of my thoughts on one big question: why would an American choose to do graduate studies in China?

Why not?

The question implies that there are good reasons not to pursue higher education in China. Indeed there are, so I’d like to get them out in the open right away. I obviously can’t cover the issues for every school and every program in China, but these are the big ones I personally encountered:

– You have to have the Chinese level for it. Remember, this whole post is about earning a degree all in Chinese, not through an English language program. To be fair, it’s not as hard as you might imagine; most Chinese programs welcome foreigners with the minimum Chinese language skills to handle the curriculum. The entrance test you’ll be given is not the same one the Chinese students must take, and the selection criteria tend to be far more lenient. Still, you’re going to need an HSK score of 6 or better, and you’re going to need to be able to write Chinese (yes, by hand) if you want to get into one of these programs.

– Inferior instruction. Ouch. Yes, I said it. In many cases, you’re simply not going to be getting a great education (by international standards) at a Chinese university. Many programs are not up to date on the latest theory in the field. Do your research.

– No strong emphasis on originality. When it comes time for term papers, teachers actually stress: don’t download your paper from the internet. Yes, they have to say it.

– Much less wilingness to experiment. As a master’s student at ECNU, I was repeatedly discouraged from doing an experiment, urged instead to rehash some grammatical topic from a slightly different angle (keep in mind the field is applied linguistics). I gather from anecdotal evidence that in many fields, the academics most interested in research go abroad (and often don’t come back).

– Less academic freedom. Your advisor makes a huge difference. I know of multiple cases where an advisor would not allow his student to pursue her own academic interests because the advisor didn’t know enough about that topic to be helpful (or perhaps the advisor wanted the student to research something else for his own reasons). Students often have no choice of advisors, which can sometimes mean that a student has very limited input on his own thesis topic.

– The “extended undergrad” experience. It’s a tough time to be a young Chinese graduate. The job market is not good. As a result, many undergraduates are continuing on to grad school to delay their job search and to try to improve their qualifications for the jobs they do eventually compete for. The result is an overall dilution of the academic passion and initiative you might expect in a graduate program.

– Boring teacher-centric teaching model. In my case, in four semesters of courses, only two placed any emphasis on discussion. (Those were my two favorites.) For most classes, the professor simply stood at the front of the class and lectured.

Then why China?

Aside from reduced cost, there is one main reason a westerner might choose to go to grad school in China over a western country: because one’s object of study is inherently Chinese. This includes Chinese history, Chinese art, Chinese language, etc.

A reader once wrote me for advice on graduate level studies, saying:

> I want to do field research on speech patterns of Chinese-Mongolian bilingual speakers in Inner Mongolia, specifically how their exposure to Chinese affects their command and use of Mongolian.

In this case, it appears studying at a Chinese university makes sense, although she shouldn’t rule out the possibility of completing coursework in the States, but going to China for the field research. But she’ll have to dig for programs like that.

In my case, because I intended to stay in China long-term, it made sense to study in China both for career reasons and for Chinese study reasons. This does not mean that I found the master’s degree a “perfect match” however. I was fortunate enough to have a great advisor, but I really struggled to stay motivated when encountering some of the issues above. And although I was in a good location to conduct the experiment I wanted to do, I received little to no guidance in its execution. There were definitely times when I wondered if doing the degree in China was worth it.

By going through it, I did gain a deeper understanding into Chinese academia, even if what I experienced as a foreigner was “Chinese academia lite.” We did take the same courses, have the same professors, and get forced to attend the same student meetings. One question I cannot yet answer, however, is if those insights are worth some of the other aspects of my education which I sacrificed.

As I mentioned above, I can only speak from my own limited experience, but I would love to hear from those of you that can add to the picture.

14

Feb 2010Florida for Chinese New Year

This year I will not be in China for Chinese New Year. I think this is the first time since I came to China in 2000 that I’ll be elsewhere for the CNY holiday.

Anyway, expect light posting for the next two weeks.

Also, check out Brendan’s latest post: BREAKING NEWS: EXPLOSIONS ROCK CHINESE CAPITAL. (I’ve always said that if there were one night of the year when an enemy could attack China and no one would notice, it would be CNY Eve…)

Happy Year of the Tiger!

Photo by Melinda on Flickr

11

Feb 2010The Sinoglot China Blogs

There’s a new China language blog in town, backed a whole group of linguistically minded writers. Sinoglot is not only a group blog, it’s also host to some other very interesting individual linguistic blogs:

– Sinoglot: language in China, eclectically.

– Beijing Sounds: Beijing sounds, mostly language, through foreign ears.

– The Annals of Wu: voices from the Yangzi delta.

– Echoes of Manchu: information & discussion the Manchu language.

– Yǔwén: Mandarin acquisition by Chinese children.

– Naxi Script Resource Centre: information on Naxi writing and language.

– Nothing Undone: an experiment in learning literary (read: classical) Chinese.

– xiao er jing: life & language among China’s Muslims.

The Sinoglot group blog is young, but if these guys can keep it up, they’ll have a mini China-centric amateur Language Log thing going. They’re writing good stuff. Here are some of my favorite posts so far:

– Squeezing in for a bite of shit [some great 屎-focused Chinese expressions] – Contractions and Logographic Writing [I also love characters like 甭, 甮, 覅, 嫑, 㬟, 孬, and 嘦] – English spelling vs Hanzi [some nice parallels here] – Scripts and banned words [good character component practice!]

Definitely a blog to watch. Note that the group blog is not merely an aggregator of the individual blogs; the group blog and the individual blogs have separate content.

08

Feb 2010The new Sinosplice Design is up!

I’d like to say thanks again to Ryan of Dao by Design for all his hard work in this Sinosplice redesign. Much of the work that went into the new site was “under the hood,” as Ryan worked out ways for me to move my “WordPress + static file hybrid” site into a modern, fully CMS-managed website. Now I can do everything (all sorts of updates) through the WordPress admin panel, which is enormously convenient. Furthermore, Ryan was really patient and professional about letting me try out some of my ideas. Some of them turned out to be deadends, but I’m really glad I got to try them out. Most often the end result was a design that was simpler, which is certainly a good thing.

One of the goals of this redesign was to make it easier to interlink blog post content and non-blog content, particularly the language-related content. Although this redesign has already done that to a greater extent, the stage is set for me to organize the content much better for the casual visitor.

Now, here are some “before and after” comparison screenshots for fun:

04

Feb 2010Website Upgrade in Progress

Comments are now temporarily suspended on all blog posts as I prepare to move Sinosplice completely off DreamHost and onto WebFaction, my new host [more info].

On the new host Sinosplice will be sporting a new look (although much will remain the same… especially for you RSS readers!). Still simple and minimalist, but more professional and up-to-date, executed by Ryan of Dao By Design, the China blogosphere’s designer of choice.

Ryan and I will be tweaking the new site over the weekend, so if all goes well the new design will go live and comments will come back on Sunday, February 7th.

02

Feb 2010The 3-2 Tone Swap Error

This post identifies a type of tonal production error which many students of Mandarin Chinese make, not only in the beginner and elementary stages, but often well into the intermediate stage. While neither years of personal observation nor the multiple appearances in the audio data for my master’s thesis experiment constitute definitive evidence, it’s my belief that the phenomenon is real, and examining it can yield useful results for both students and teachers of Mandarin Chinese. I’m dubbing the error the “3-2 Tone Swap.”

The Error

Note that the term “error” is used in the error analysis sense, meaning that it is committed systematically, and is not merely a random mistake (which even native speakers make from time to time).

The error occurs, in two-syllable words, when the tonal pattern is 3-2. Many students will pronounce the 3-2 tone pattern incorrectly as 2-3. Some typical examples:

- 美国 (Correct: Měiguó, 3-2 Tone Swap Error: Méiguǒ)

- 法国 (Correct: Fǎguó, 3-2 Tone Swap Error: Fáguǒ)

- 五十 (Correct: wǔshí, 3-2 Tone Swap Error: wúshǐ)

- 可怜 (Correct: kělián, 3-2 Tone Swap Error: kéliǎn)

Personal History

I remember quite clearly when I discovered myself committing the 3-2 Tone Swap error. I had learned the word 可怜 (kělián) in Hangzhou from a friend. But I noticed that although I had “learned” the word, every time I tried to use it, my friend would correct my pronunciation. “No, it’s ‘kělián,’ not ‘kéliǎn.'” This was extremely frustrating for me, because I thought I had learned the word, and I was pronouncing it wrong even when I knew that the tones were 3-2. At the time I dismissed it as just a “problem word” that I would get eventually.

Around this time I became super-vigilant about my tones. I realized that although I was communicating pretty well, I was still making a lot of tone mistakes. Part of this new awareness came when I realized that native speakers were correcting me all the time using recasts, but I had previously been oblivious to it.

A typical conversation went like this:

Native Chinese speaker: 你是哪个国家的? [Which country are you from?]

Me: 美国。 [The USA.]

Native Chinese speaker: 哦,美国,是吗? [Oh, the USA, huh?]

Me: 对。 [Right.]

After having this same exchange about a million times, I had started to assume that it was just a natural conversational pattern in Chinese to have your country repeated back to you for verification. Yeah, it seems a little strange and inefficient, but there are stranger features of the Chinese language.

What I eventually came to realize, however, was that when I gave my answer, 美国, I was routinely mispronouncing it as *”Méiguǒ” (3-2 Tone Swap error), and then the other person was both (1) confirming the information and (2) modeling it for me in his response, which included the correct form “Měiguó” (a classic recast).

When I finally realized this, it sort of blew my mind. I had thought my tones were already pretty good, but I had been pronouncing the name of my own country wrong all this time?? Learning Mandarin Chinese is, if nothing else, an exercise in humility. There was nothing to do but hunker down and try to reform my pronunciation. While I found it easier to focus on high-frequency words like 美国, it quickly became apparent to me that the 3-2 tone swap issue was rampant in my pronunciation.

Research

Although the 3-2 Tone Swap phenomenon cropped up in my own experiment on tonal pairs for my masters thesis, it was not the focus of my own research. If anyone knows of specific research done on this phenomenon, I would love to hear about it.

The data in my own experiment showed some interesting patterns. While errors in 3-2 tonal pairs were clearly more common than in the other two tonal pairs I examined (1-1 and 2-4), there were some inconsistencies. Namely:

- Errors were notably less frequent for numbers (e.g. 50, “wǔshí”)

- Errors were less frequent for one’s own country (e.g. “Měiguó”, “Fǎguó”)

While all subjects illustrated the first trend, the second was particularly well demonstarted by an intermediate-level French subject, who routinely pronounced “Fǎguó” [France] correctly, despite the existence of a 3-2 tonal pair, but then also routinely pronounced “Měiguó” [The United States] incorrectly as *”Méiguǒ” (the 3-2 Tone Swap).

What this suggests is that although some tonal pairs seem to take longer to master, the mastery is not categorical. In other words, you don’t suddenly “get” the pronunciation pattern and then just switch over to correct 3-2 pronunciation for all words where it occurs. Acquisition of the 3-2 tonal pair appears to be occur more on a word-by-word basis, making it largely a matter of practice, practice, practice (which also explains the better performance with numbers). This mirrors my own experiences.

Questions

Tonal mastery is a long process for most students, with the 3-2 tone pair appearing to be one of the last patterns to acquire. Why?

I suspect that there is a relationship between the 3-2 Tone Swap error and the 3-3 tone sandhi (in which 3-3 tonal pairs are systematically converted to 2-3). The learners that exhibit the 3-2 Tone Swap error typically do very well with their 3-3 sandhi. Could learners be internalizing but then overextending the 3-3 tone sandhi rule to include not only 3-3 pairs, but also 3-2 pairs? It’s certainly possible.

Again, if anyone knows of any research into the above phenomena, I would appreciate links or more information!

31

Jan 2010A Peek at Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek Art District

I’ve recently made two trips to Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek Art District (more info). It’s in the Moganshan Road area (Google map), and it’s probably easiest reached by taking the subway (Line 1) to the Shanghai Train Station, then Changshou Road west over Suzhou Creek, then making a right, following the creek north. The road there deadends into a complex of buildings which make up the art district. You’ll see a bunch of graffiti as you head in.

Some of the graffiti in the area:

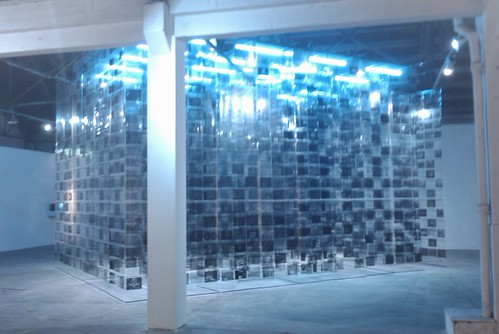

The when I went just this month I checked out the work of a an art collective called Liu Dao (六岛), AKA island6. The group likes to mix traditional art forms with newer media, like animated LED displays. Quite interesting (check out their website for examples).

Yesterday I checked out the exhibits at “Things from the gallery warehouse 2” [PDF intro].

> In the Fiction between 1999 & 2000 (2000), Hu Jieming takes on a more universal challenge, the daunting proliferation of media and information engendered by the Internet. Hu’s huge information labyrinth is constructed from screen captures collected from across the Web and network television during the twenty-four-hour period from midnight of December 31, 1999, to midnight of January 1, 2000. It represents the difficulties we all face in navigating through a world where information can be empowering, but only if we can filter through the barrage of useless images and texts that cloud our minds and dull our instincts. Hu asks, “What will we choose to do when we are controlled by information and lose ourselves?”

I liked this one a lot… The piece actually makes up a maze that you can wander through. There are so many screen captures which make its point rather well: there’s no way you can look at it all. You find yourself wanting to just get out before too long. Nicely done.

This other piece, Massage Chairs, while perhaps less aesthetically appealing, answers an engineering question I’ve always had: what, exactly is inside those electric massage chairs?? The massage chairs below were stripped of their padding, the moving parts laid bare, but still powered up and moving.

> Massage Chairs – Then Edison’s Direct Current was surrendered To the Alternating Current (2003) consists of six massage chairs of various designs – found objects, readymades – stripped of their upholstery. Still in operation, their mechanisms are clearly visible, the cogs and belts moving the various shapes intended to knead and gently pummel the backs of human bodies requiring relaxation. Without their padding and soft surfaces, the chairs themselves are skeletal, strangely anthropomorphic and not unreminiscent of electric chairs. The sounds they emit,

the whirrings and rhythmical clickings echo ominously in the gallery interiors they now occupy, evoking a response that is a far cry from any of the desired effects of massage.

Finally, the pieces at Mr. Iron were really fun and imaginative. It’s that style where sculptures are created out of old scrap metal. Some of them were really amazing, and quite a few are strongly commercial (see the site’s classics section for examples.) My favorite one, already long sold, was a recreation of Giger’s Alien (sorry, it’s a picture of a picture with a cell phone camera, so not very clear):

I guess it’s pretty obvious that I’m personally most interested in art’s intersection with technology, but there are lots of different styles of art in the Suzhou Creek Art District, so I recommend you check it out, no matter what your interest. A word of warning, though: there’s extensive construction going on right now (2010 World Expo prep?), so it’s quite messy.

26

Jan 2010Hongbao Fantasy

I originally found this video introduced by a Chinese friend on Kaixin Wang as “a Chinese film way more fantastic than Avatar”:

Transcript for the students:

> 老师:你的孩子又考了全班第一。

> 家长:谢谢谢谢。(递红包)

> 老师:你在伤害我。

> 医生:好了,病人终于脱离危险了。

> 家属:谢谢谢谢。(递红包)

> 医生:你在侮辱我。

> 官员:你的审批手续全办好了。

> 商人:谢谢谢谢。(递红包)

> 官员:你在藐视我。

> 警官:恭喜你啊,考试通过了。

> 司机:谢谢谢谢。(递红包)

> 警官:请你尊重我。

> [source (with additional sarcastic commentary)]

The video is a public service message urging people not to accept hongbao (red envelopes full of money) for what they should be doing anyway for the good of society. (And apparently that idea is still rather outlandish in modern China.) Anyway, the video does a good job of educating us foreigners in what situations Chinese people typically give their “thank you notes”:

– A teacher tells a mother that her child is the top student in the class

– A doctor informs someone that his family member is no longer in danger

– A government official announces that a businessman’s procedure is complete

– A police officer announces that the student has passed his (driving) test

I know some students of Chinese that spend a lot of time on Chinese news websites. I’m finding that Kaixin Wang‘s 转帖 (“repost”) system is way better, acting as a combination RSS reader / Digg / SNS site (so the content is filtered by your young Chinese friends). I highly recommend it as a source of interesting material.

Apparently, though, some of the posts (like the one I refer to above) mysteriously disappear… so read quickly, and enjoy!

24

Jan 2010Guangming Commits Cheese Fraud!

Gustatory investigation confirms what should be obvious by a cursory visual check: the single-serving substance Guangming (光明) is selling is definitely not cheddar cheese (切达奶酪).

16

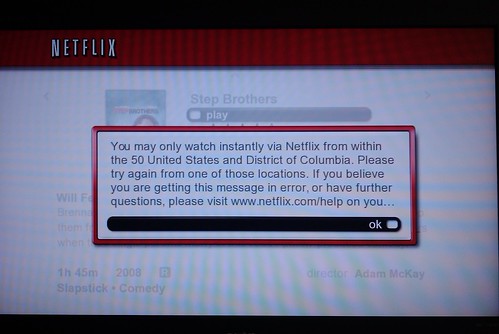

Jan 2010Streaming Netflix Movies on a PS3 in China (FAIL)

I got a PS3 late last year, and soon after Netflix announced a new feature: the ability to stream unlimited movies on the PS3 for only $8.99/month.

This got me thinking… even if you only pay 5 RMB per pirated DVD in China, it only takes about 12 movies per month to hit the equivalent of $8.99. I know many people here who watch far in excess of 12 DVDs per month, and they rarely ever watch the same DVD again, leading to piles and piles of unwanted DVDs, and just tons of DVD waste in general. And this Netflix plan is actually a legal alternative.

The way it works is you sign up online (yes, with a credit card), and then they immediately mail the Netflix PS3 disc (required for streaming) to your US address. Your two-week free trial starts at the same time.

There’s not really time to receive the disc in the States, and then ship it to China and still have time to enjoy the free trial. The people at Netflix are very nice and accommodating, however. So I had my dad mail the Netflix disc to me in China, then called up Netflix’s toll-free number (a free international call using Skype). I explained that I had received the disc, but hadn’t been able to try it yet (they can verify this), so the free trial had expired. Could I have another free trial? Oh, and by the way… I’m in China.

The customer service representative was happy to help me out, but let me know she wasn’t sure if it would work in China. Netflix is working on offering the streaming service internationally, but the movie studios are holding it up. I was hoping that Netflix was depending on very few people going to the trouble of shipping a disc to a US address and then re-mailing it to another country.

Anyway, after I inserted the Netflix PS3 disc, there was a rather long wait (2 minutes?) before the screen came up with the verification code. My customer service representative used that to reactivate my free trial. I could then browse all movies through the PS3 interface. I was told to try playing one. That’s where I got this message:

So Netflix is quite thorough in their streaming setup, it would seem. I’m disappointed; I was hoping Netflix could give me a (almost) legal alternative to buying pirated DVDs in China, and at a competitive price point. I would definitely pay Netflix a monthly fee for this service because:

1. It reduces waste

2. It rewards the creators of the films and the legitimate distributors

3. It’s super convenient and competitively priced

For now, the best similar alternative is very illegal: download movies to one’s home computer via bittorrent, then stream them to the PS3/TV across the network using PS3 Media Server.

What Netflix is doing really gives me hope that a legal, economically feasible alternative is on the way, though.

14

Jan 2010Worry about the Internet in China

If you’re not in China, it may be hard to imagine the extent of the worry caused by Google’s recent announcement that it may just pack up and leave China. Sure, you can analyze the political and financial angles, but for most of us, this recent news forces our minds to leap straight to the worst-case scenario that will affect us personally: what if all Google services get blocked in China?

Many (including this Chinese language summary of the situation) are concluding that using a VPN might just have to become an essential “always-on” part of using the Internet in China. My fear is that if that day comes and VPN usage becomes so widespread, it might not be long before that method too is struck down by new GFW technology. I’m really afraid of being stuck in that information void.

It’s not just about one big company operating in China. It’s about how in recent years, various internet services have made us feel much more connected to our loved ones half a world away. It’s about how the internet is becoming such an integral part of our lives, through email, through IM, through social services, through smartphones… and wanting to be a part of that progress. No company is more key to that progress than Google.

A Chinese friend of mine recently admitted to me what I didn’t want to say myself: “if they go so far as to block all Google services in China, I don’t even want to stay here anymore.”

This is how deep the worry runs for many of us.

If you’re not up on the situation, I recommend these articles:

– Google and China: superpower standoff (a good blog post roundup on the Guardian)

– Earth-shattering news and a faked interview (Danwei’s angle)

– Google’s China Stance: More about Business than Thwarting Evil (TechCrunch)

– Soul Searching: Google’s position on China might be many things, but moral it is not (TechCrunch)

– Google v. Baidu: It’s Not Just about China (TechCrunch)

– The impact of Google’s bold move

12

Jan 2010Cosmetic Surgery Culture

ChinesePod co-worker Jenny had occasion to visit the plastic surgeon’s office recently, and she took away some interesting (although not terribly surprising) insights:

> 1. Most popular form of plastic surgery in China: an even divide between all-time favorite double eyelid operation (双眼皮/shuang1yan3pi2) and new comer face-slimming injection (瘦脸针/shou4lian3zhen1).(Note, many Asians are born with single eye lid, but double eye lids are considered beautiful. We are also obsessed with a small face. My take is that Asian faces tend to be flatter (hence bigger). I don’t know what’s ugly about that, but there is an industry dedicated to making one’s face smaller, everything from lotion to plastic surgery).

> 2. The consumers: girls in their 20’s top the list. The aforementioned operations were monopolized by these girls. There were literally 5 girls coming in for one of those treatment every hour.

See her blog post for the rest.