25

Jul 2010China Blog Death and Relevance

I enjoyed Kaiser Kuo’s recent Sinica podcast on Popup Chinese featuring Jeremy Goldkorn of Danwei.org and Will Moss of Imagethief. They started off with the provocative statement that “the English language China blog is dead,” and went into some analysis of how things are different now than they were. Their analysis seemed pretty spot-on to me.

This is an issue I’ve been thinking about for a long time: how the “China blogosphere” has changed, how I still fit in, and how it’s still enjoyable or worthwhile. I think when I first arrived in China and was doing various English teaching jobs while I furiously studied Chinese in my free time, aside from intangibles like Chinese learning and friendships, my blog and website was the most important, lasting thing I created. It’s what led to a job at ChinesePod in 2006, the point at which I officially embarked upon what would become my career. Blogging, for me, had to take a backseat, and it has to this day. The “top ideas” on my mind were less and less often blog topics as work usurped my focus.

I’ve revisited this same topic as I’ve considered whether or not to put more time or effort into the China Blog List. There are just so many blogs out there now that organizing them really does seem too big a task for one tiny directory. It’s a task that needs to be crowd-sourced or done through social media somehow, if it even needs to be done at all. That site still has potential (and good Google rank for “China blog” and “China blogs”), but the concept needs to be rethunk. In the meantime, it’s just no longer relevant.

I was pleased to hear those guys mention my blog in their podcast as one of the ones that’s been around the longest, but as the list of blogs went on and on, I had to think, how do these guys have the time to read so many blogs? Like Will Moss said in the podcast, I’ve found that the decreasing signal-to-noise ratio has just led to less overall blog reading.

This afternoon I had the pleasure of sitting in on a talk at Glamour Bar hosted by history professor Jeffery Wasserstrom of China Beat as he discussed various issues with the New Yorker’s China correspondent Evan Osnos. The topic was writing and blogging, and they kicked off the discussion by mentioning Sinica’s take on the issue. Both writers had begun blogging relatively recently, so Evan referred to them as “post-modern, or, perhaps, ‘post-mortem’ bloggers.” Both Wasserstrom and Osnos were optimistic about the role of blogging. Evan was particularly happy about the recent proliferation of translation bridge blogs like China Geeks.

One of the more interesting questions thrown out by the crowd was basically, “yeah, you both write well about China, but how much do you guys (or anyone) really understand China?” Both men were humble in acknowledging the limits of their knowledge, but I liked Dr. Wasserstrom’s response that despite the smallness of what we can know, the view from outside offers a different perspective which contributes in an important way toward the full picture. This closely parallels the view I take on language learning: the native speaker perspective should be combined with the learner perspective to reach a fuller picture of the language more relevant to the learner.

I was amused to find Sinosplice included recently in a list of Shanghai-related resources on National Geographic:

> A China-focused blog that includes Mandarin speaking tips and apolitical, largely irreverent (and in some cases irrelevant) observations about Shanghai and the rest of the country, among other tidbits.

“Irreverent and irrelevant.” Heh, I can live with that. I have to say, though, that this blog is only occasionally relevant to Shanghai.

But relevance is always an issue on my mind. The new business is getting quite busy, and while I have less free time than ever, it’s a rich source of new observations and blogging material about Shanghai and learning Chinese. I won’t keep those bottled up. The search for relevance is not fruitless.

22

Jul 2010Tooltip Plugin Color Feedback, Please

So the pinyin tooltip WordPress plugin I mentioned before is slowly but surely coming along. We’re alpha testing now, and discovering weird discrepancies between versions of WordPress. Hopefully those won’t be too hard to fix.

One of the options supported by the plugin is choice of tooltip background. Sinosplice currently uses plain white, but the script it’s based on uses a nice blue color. Here are some of the options I’ve put together (note: tooltip boxes and text are not actual sizes or proportions):

If you’re interested in using this tooltip, is there any default color you’d definitely want? If so, please let me know. As things stand now, I think I’ll go with the first four below (dropping the black one).

17

Jul 2010The Pharmacy Count

While at the pharmacy the other day with my friend Chris, we came upon what seemed like a typical example of Engrish:

Funny, we thought… “the count” instead of “the counter.”

Only as we were leaving did we notice the guy behind the counter:

The Sesame Street character “the Count” is known for his rather clever name. Even a kid can get the pun. How does his Chinese name fare in terms of cleverness? Not too well, I’m afraid. According to this site, his Chinese name is simply 伯爵, a translation of only one of the meanings of the Count’s name, meaning “count” or “earl.”

What would a more clever translation of the Count’s name be? All I can think of is maybe something related to 叔叔 (“uncle”) and 数数 (“to count up”), but once you change the tones it doesn’t really work. (Not to mention that he very clearly looks like a count, not an “uncle.”)

15

Jul 2010Fei Cheng Wu Rao: what’s the appeal?

OK, I admit it. This Chinese TV show called 非诚勿扰 (English name: If You Are the One) has ensnared me. It’s just silly dating game television, but I find it interesting for a bunch of reasons. Here is the basic premise of the show, explained by Hello Nanjing:

> The basic concept of the show is that 24 girls will stand in a line, each atop a podium with a light hanging over their head. Facing them is one boy, who will at first secretly choose one of the girls to be his date. Then, he reveals some basic information about himself, after which each of the girls will decide whether he is ‘date-worthy’ or not.

> If a girl doesn’t like him, she will turn the light above her head off. If all 24 lights go off, the boy loses. If some lights remain on after the boy’s introduction, the boy may choose two or three of the girls for ‘future communication’. He also has the option in this case to choose a girl who turned her light off.

> Finally, with three girls left, the boy will ask another round of questions, after which he will make his final choice. If the girl accepts, they may walk towards each other, join hands, and head off into the sunset for a future date and possible romance.

The name of the show, 非诚勿扰 (as well as the English name), is the same as a rather boring movie by Feng Xiaogang (the article quoted above mistakenly included a shot of the cast of that movie). It’s taken from a line used in personal ads, which literally means, “if you’re not sincere, don’t disturb me” but would be translated more along the lines of “serious inquiries only please” in English language personals.

OK, so what’s so good about this show? It’s hard to say, but here are my guesses:

– It’s interesting to see which guys get shot down immediately by the 24 female candidates, and which can make it to the very end. (I evidently still have a lot to learn about the psyche of Chinese women.)

– The background music, which is always the same and used in every show, is hilariously cheesy, and yet so appropriate.

– The concept is so simple that it’s easy to follow the show, but there is enough interesting language used that I feel like I still learn useful words and phrases.

– The host, 孟非, and his “psychological analyst,” 乐嘉 make for an entertaining, bald-headed duo. They don’t feel like typical moron TV show hosts.

– 乐嘉 in particular is entertaining. He invented a personality analysis system based on colors which my wife had to use for her job (and I’ve been hearing about for years). At first you think, “who is this smiley, smug little bald man?” but then you really start to like him. And he totally casts a spell over all the female contestants, many of whom thank him specifically, all teary-eyed, when they finally leave the show. This guy is interesting!

– Although the show is filmed in Nanjing, participants come from all over China, which means you get to hear a wide variety of accents.

– The show has attracted the attention of the media censors for its reflection of shameless materialism, and even had some kind of pornography scandal.

– There’s no dancing, cross-talk, acrobatics, or skits, and very little singing.

– It could be staged, or at least quite fake, but the show has captivated China’s younger generation; in some small way, this is modern China. And it wants to be noticed.

Anyway, if you’ve never heard of the show or never bothered to watch, I recommend you give it a chance.

– 非诚勿扰 on Baidu video search

– 非诚勿扰 on Tudou

– 非诚勿扰 on 百度百科 (everything you could possible want to know about the show, but in Chinese)

11

Jul 2010Churchill and Hitler: Evil Supervillains?

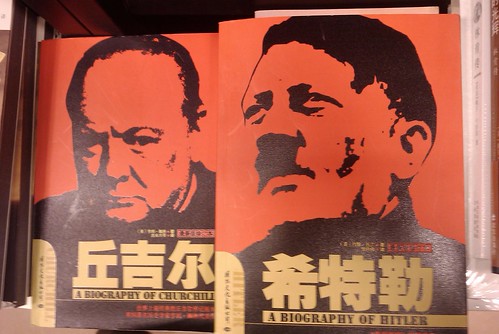

Yesterday in the bookstore I noticed these two books, titled 丘吉尔 (Churchill) and 希特勒 (Hitler):

Now am I crazy, or do these two historical figures both look really evil, perhaps Churchill even more so than Hitler??

Apparently this was just a bad choice of photo (and color) in the cover design, though; if you click through to either Churchill’s or Hitler’s Amazon.cn pages, you see lots of other books in the series. Only Mussolini looks as evil as these two.

According to the introduction on Amazon, the book about Churchill is not an explanation of how he was actually Britain’s greatest supervillain. That’s a relief.

09

Jul 2010Joris Ivens Week

I just got a tip from an AllSet Learning client that there will be some special screenings of the films of Joris Ivens at the Expo’s Dutch pavilion this weekend (July 9~10). So maybe after checking out the new Shanghai Apple Store we can go get a dose of real culture. (Wow, that sure sounded snobby. I own a Mac!)

Here is the description:

> During the weekend of 9 and 10 July at the World Expo in Shanhai, Joris Ivens will be honored in a true “Joris Ivens weekend.” On Friday evening and Saturday afternoon and evening 13 films by Joris Ivens are screened. The films are grouped around six themes: Introduction / Stories in China / Against Facism / Avant-garde / China / Poetry and Cinema. Mrs Loridan-Ivens and the European Foundation Joris Ivens will be present to introduce the films. The theatre space at the Dutch Culture Centre will also host a small exhibition of photographs of Joris Ivens and Mrs Marceline Loridan-Ivens.

> One of the films is The 400 Million (in 1938), showing Mr. Zhou-Enlai and Mr. Zu De [ed. Zhu De?] with music of The March of the Volunteers (which later became the National Anthem of the People’s Republic of China). Don’t miss the unique opportunity of viewing the Chinese culture and the turbulent 20th century through the camera of Ivens.

Sounds interesting. You can reserve tickets on the Joris Ivens site.

06

Jul 2010Chinese Characters: not so magical

Mark over at Pinyin News had a great rant the other day reacting to a New York Times article which exoticized Chinese characters.

It’s funny, when you first learn anything about Chinese characters, you learn that they’re a “writing system.” Fair enough, seems simple, right? But you don’t have to study long before you’re bombarded with all kinds of ideas about how the characters are the language, or the characters are the essence of the culture, or the language could not exist without the characters.

And Mark is, of course, completely right to say that it’s all nonsense. He declares this so vehemently and at such length that the ordinary person might start getting suspicious, but it’s all true.

photo credit: DigitalFreak

Language is a fundamental part of the human condition. Writing is a technology. It’s an important technology, with a tremendous influence on culture and human civilization, but it’s still a technology. As Wikipedia puts it, “writing is the representation of language in a textual medium.” In human history, this representation always follows the representation we call speaking. Theoretically it shouldn’t have to; that’s just the way it works in practice. (If you don’t like it, turn to sci-fi.)

Could Chinese exist without characters? Yes. It existed for a long time before characters came along. I’m not advocating the abolition of characters; I think that will work its way out naturally in good time (accelerated by the internet). Mark feels quite strongly about this issue, though, which you can tell by reading the original article.

One of the comments in response to Mark’s post caught my attention:

> Nongandwong said,

July 2, 2010 @ 8:55 pm

> Wonderful post, pity lots of people will have read about magical Chinese from that NYT article.

> What they should have done is get her to try and explain the etymology of the character 你 and how it relates to the meaning. This was the character that made me give up looking for character etymologies because the explanation made less sense than just memorising the strokes!

I had to laugh out loud when I saw this comment, because I had exactly the same experience myself. For me, the process went like this:

1. Try to learn characters by rote, as instructed by teachers. Hate it. Feel strongly that there must be a better way.

2. Discover Heisig’s method. Enjoy that breath of fresh air. But then start to doubt a little.

3. Try to abandon Heisig’s method in favor of learning actual character etymologies. Fail miserably, again and again and again (but starting with 你).

4. Return to Heisig, but with a healthy longing for actual etymologies (except when they’re a hopeless, ridiculous goose chase).

For those of you that are wondering, the etymology of 你 goes something like this (courtesy of Wenlin):

> 你 (nǐ): From 亻(人 rén) ‘person’ and 尔 ěr ‘you’.

> Etymologically 你 nǐ is a “colloquial variation” of 尔(爾) ěr; the two sounds nǐ and ěr both derive from ancient nzie (–Karlgren).

OK, so now all we need is something for “尔(爾) ěr” that makes sense, and we’re done, right?

> Which came first, 尔 or 爾?

> Wieger cites this explanation for 尔:

> “从入丨八, 会意。八者气之分也。”

> Then 爾 came from 尔 (phonetic), 巾 ( = 两 a balance) and 爻爻 weights on both sides, to give the meaning “symmetry, harmony of proportions”.

> Karlgren (1923) says of the form 爾, “…original sense and hence explanation of character uncertain”, and considers 尔 an abbreviation.

> The pronunciation was once something like nzie. This produced both ěr and nǐ, the latter written 你 nǐ, which is the modern word for ‘you’. Now 尔 is only used in a few adverbs and archaic expressions, and in foreign loan words.

Riiiight… This is the word for “you,” also the first character in the basic Chinese word for “hi” (你好), which is likely the first word you’ll ever learn. I guess it does make rote memorization look pretty good.

01

Jul 2010Green Tea Sprite

Once upon a time I blogged about a short-lived beverage experiment known as Spicy Sprite, and before that, Mint Sprite. Recently someone called to my attention the new Green Tea Sprite. Being the long-time Sprite connoisseur that I am, I had to try it.

It tasted like Sprite, but only… (wait for it) …with green tea in it.

It wasn’t altogether bad, I guess. Not nearly as bad as Mint Sprite, anyway.

The Chinese name is 冰+茶味雪碧. I’m not sure exactly what that “+” in there is trying to prove.

28

Jun 2010PHP Developer Wanted in Shanghai

This is just a quick post to say that I’m looking for a PHP developer in Shanghai for some project work. It’s one project, but it could lead to many.

(And no, this is not related to the WP plugin I’ve mentioned. Different project. This one pays in pink bills, but you need to be in Shanghai!)

Just send me an email if you’re interested.

23

Jun 2010Misgivings about SRS

Earlier this year the Global Times did an article on using SRS (spaced repetition software) technology to “Learn Chinese in a flash.” The journalist interviewed both me and Dr. Orlando Kelm about the issue, but most of what we said didn’t actually make it into the article. I’m going to use the content of that exchange to finally address my misgivings about SRS.

My SRS misgivings are grouped into three main points below, and I’ve added in some of Dr. Kelm’s input, with his permission.

SRS is a way to enhance your language studies, not a substitution for them

Back in the good old days, we students used to take our vocabulary lists and make flashcards out of them. As we amassed stacks and stacks of these flashcards, it was hard to systematically review them properly, and to keep track of which stacks of cards had which vocabulary. SRS completely solves this problem with a tidy little review algorithm and a feedback mechanism which you interact with as you review your vocabulary. This is great. Those of us who were too lazy to create stacks and stacks of flashcards can now feel vindicated; we will never have to, because technology has saved us from all that arduous flashcard management.

The problem, however, is that SRS is sometimes over-emphasized to the point that it almost seems like a “language acquisition method.” Especially for the analytical-minded, it can be easy to get lost in the efficiency of the review system and all the pretty stats, forgetting that memorization of vocabulary is only one part of language acquisition. If the SRS-obsessed student is not getting plenty of natural target language input and speaking practice, he’ll end up the linguistic equivalent of the guy at the gym with bulging upper body musculature but pencil legs.

Dr. Kelm warns against the “one method for everything” approach as well:

It seems like every time we discover something that is good in one area (e.g., SRS that helps in aiding rote memorization) the tendency is to try to apply it in every other area (e.g., speaking a foreign language). I have seen the same thing with lots of second language theories. For example TPR (total physical response) is a theory where people are supposed to physically use their senses while learning a language (actually open a door when saying “I open the door”, actually taste the food when they say “I am eating a banana). Great, TPR may be OK in some instances, but then people try to apply TPR to every aspect of language learning. It just gets crazy after a while. To me the same issue comes up with SRS. Just because it is good for rote memorization, doesn’t mean that it will be good for all aspects of language learning.

Dr. Kelm reminds us about what else is important that is outside the realm of SRS :

The biggest issue here, as related some of the limitations of SRS, is that of input vs intake, schema theory, and scripts. A gigantic part of language learning is related to CONTEXT. I’m sure there are times when you can recall the exact moment when you heard a new phrase in Chinese, learned a new word, or did something in another language.

For example, last month when I was in China a seller came up to our car and asked my guide if he wanted to buy something. All he said to the seller was “mai bu qi” (I can’t afford that). For me it was the perfect moment because I saw how a native speaker reacts to the sellers. Where I would have just said “bu yao” or “bu yong“, there was something cool about hearing “mai bu qi“. The phrase stuck in my mind and I’ll be able to use it from here on out. This is a great example of how context affects our learning. The more we can create context for learners, the better we retain the foreign language. Note that this is not related to frequency of occurrence or frequency of review (principles of SRS), but more to the impact of the moment. SRS doesn’t necessarily take this feature into account.

Second, language learning also happens in chunks and people learn these chunks in scripts that we follow. For example, if you go to a fast food restaurant to make an order, at some point the cashier will say “Is that for here or to go?” You know the pattern, you expect this question to come up, and so you are prepared to answer it. Even if you don’t hear the question exactly, you can still guess at what was said. It’s part of the “script” that we all follow when ordering fast food. When language learning relates to these chunks and scripts, it helps to make things stick. Note again that this is not related to the frequency of occurrence and isn’t where SRS will shine. (I should probably add that ChinesePod does a really good job of creating short dialogs that help provide this context and simulate these scripts. They recycle vocabulary in various contexts well.)

SRS and the DIY factor

Creating flashcards is a meaningful activity in itself. The act of creating the cards, with each word carefully scrawled by the student (and maybe even a picture or two!) contributes to the learning. Anyone who has ever used flashcards can tell you there’s a big difference between making your own and buying pre-made flashcards.

Ideally, the words and sentences added to your SRS come from your own experience, or from the material you are personally interested in studying. This makes the learning more personal and the results more satisfying. Many students, however, are reviewing ready-made vocabulary lists, pre-loaded into the SRS. This type of review isn’t worthless, but because the learner’s degree of involvement is so much lower, each word’s “memory imprint” is much fainter. It’s also much easier to simply toss aside and forget a digital “stack” of flashcards that took 3 seconds to download, compared to a personalized list one has invested time and effort into.

Using SRS well is a skill

This is the part that no one really expects, because it’s nice to think that technology has solved our problems. The truth is that using SRS effectively is an entirely new skill. I mentioned already that ready-made decks are less likely to be effective, but even an active learner carefully looking up new words and adding them to SRS (with some context) can easily go wrong.

I’ll give you a personal example. I was reading a Lu Xun story, and it contained a fair amount of vocabulary with which I was unfamiliar. After looking up the new words, I dutifully copied them into Anki (my SRS client of choice). There was a fair amount of vocabulary just from that Lu Xun story. Over time, I found that the Lu Xun vocabulary just wasn’t sticking. The words were semi-archaic, and I had virtually no chance of running into them in my modern daily life in Shanghai. I found they were useful only for reading Lu Xun (or possibly other Chinese literature of that era), and yet I wasn’t spending a lot of time reading that literature. The vocabulary was effectively “clogging up” my SRS review sessions as I had to repeatedly review those words, which meant I had less time to spend on review of more useful vocabulary, and I was rapidly losing motivation to use SRS altogether. When I found myself going a week or more without doing any review at all, I eventually realized that I had effectively killed my review sessions and needed an “Anki Reset.”

Including too much obscure “recognition only” material is not the only pitfall; other typical mistakes include lack of sufficient context, overly long sentence examples, and insufficient consideration of what is actually useful in one’s active vocabulary. It’s the memorization of vocabulary which one is able to actually use in conversation that is the most satisfying, after all. Failure to accomplish this essentially amounts to “vocabulary hoarding,” not proficiency in the target language.

Since using SRS properly is a skill which must be practiced, it demands time in itself. Learning to use SRS well and getting into the the habit of using it will take time, which could otherwise be devoted to listening or speaking practice. Is it worth it? For some, the answer is an unabashed yes, yes, a thousands times YES! but for many students the answer is not so clear-cut.

17

Jun 2010Chinese Restaurant Worldwide Documentation Project

I recently stumbled across this Flickr group called Chinese Restaurant Worldwide Documentation Project. It has this intriguing description:

> Chinese Restaurants – Worldwide, except China and Taiwan. Here you’ll find the culture ‘clash’ and culture ‘mash’ with all the societies they have adapted to.

Below are a few examples of photos from the group pool, taken at locations all over the world.

Genoa, Italy:

Santa Cruz, Bolivia:

Brooklyn, New York, USA:

Antwerp, Belgium:

Aguas Calientes, Peru:

Paphos, Cyprus:

Of course, there are many more in the pool.

15

Jun 2010Quotes from Tales of Old Peking

It’s been a while since I got my copy of Tales of Old Peking. I’ve taken my time going through it. It’s a patient a book, its contents largely magazine-style, most articles only indirectly related to each other. A book like this doesn’t demand your attention or keep you frantically turning those pages until the end. But it’s still a fascinating collection of accounts of old Beijing, through the eyes of foreigners. Below are a few of the quotes I enjoyed the most:

On the City

Page 92:

> I visited Peking about thirty years ago. On my return I found it unchanged, except that it was thirty times dirtier, the smells thirty times more insufferable, and the roads thirty times worse for the wear. —Admiral Lord Charles Beresford, The Breakup of China, 1899

Page 14:

> … But in spite of so much that disgusts and offends one in this wreck of an imperial city, who can deny the charm of Peking, that unique and most fascinating city of the East! –Lady Susan Townley in My Chinese Note Book, 1904

Page 135:

> …if you have once lived in Peking, if you have ever stayed here long enough to fall under the charm and interest of this splendid barbaric capital, if you have once seen the temples and glorious monuments of Chili, all other parts of China seem dull and second rate… when you have seen the best there is, everything else is anticlimax. –Ellen N. LaMotte, Peking Dust, 1919

I may be a member of the Shanghai faction, but I’m not totally immune to the charms of Beijing either.

On Foreigners in China

Page 26:

> As I am here and watch, I do not wonder that the Chinese hate the foreigner. The foreigner is frequently severe and exacting in this Empire which is not his own. He often treats the Chinese as though they were dogs and had no rights whatever – no wonder that they growl and sometimes bite. —Sarah Pike Conger, Feb. 1, 1899

Page 72:

> He has been in Peking nearly four months now, in a comfortable Chinese house studying Chinese history, smoking opium in spite of the prohibition, and frequenting only the Chinese with whom he appears thoroughly at home.

The more things change, the more they stay the same?

11

Jun 2010Pinyin Tooltips: a Plugin Is Coming

Over the years, I’ve been asked by quite a few people about how I do the pinyin mouseover tooltips on Sinosplice. (Here’s an example: 中文.) It’s a combination of HTML, CSS, and javascript, none of it terribly complicated. (My friend Brad helped me with the javascript parts.)

Anyway, now that Sinosplice has been redesigned, it feels like it’s time to do the tooltips right: as a WordPress plugin. That way WordPress upgrades will be (mostly?) unaffected, and I can easily share the tool with other bloggers. I’m working with a developer now to create the plugin, free and opensource.

Basically what it will do is:

– Add the CSS you need, giving you a few options

– Add the javascript you need

– Add a quicktag to the HTML text editor to facilitate addition of tooltip code

The good part is that the effect is general enough that it doesn’t have to be pinyin-specific, meaning it could work for regular English blogs, blogs about Japanese, etc. I know there are a few WP tooltip plugins out there, but none of them offer quite what I want, as a blogger frequently writing about Chinese for learners.

I’ll be presenting the idea at Shanghai Barcamp tomorrow; maybe I’ll get some good ideas there. Good ideas are always welcome in the comments, too, of course!

08

Jun 2010Barcamp, ShanghaiSolved

I’ve been especially busy with AllSet Learning lately. Lots of exciting developments there; pretty soon I’ll be starting up a news blog for that site. If you’re in Shanghai and interested, it’s a good time to get in touch.

Next Saturday I’ll be attending Shanghai Barcamp. I meant to do it these past two years, but never quite got around to it. Third time’s a charm, I guess? ChinesePod CEO Hank will be there, as well as Xindanwei CEO Liu Yan. I expect to see some other familiar faces, such as Micah and Kellen. Should be a thought-provoking, geeky day.

I noticed one of the sponsors of Barcamp this time is ShanghaiSolved. I’ve heard this idea before, and this implementation looks pretty good. Basically, some people ask questions about Shanghai, and other people answer them. Kinda like Ask Metafilter, or Yahoo Answers, or Aardvark, but just for Shanghai. I’m curious to see if this will take off. It’s got some questions up, about “must-see places” and rock climbing and VPNs, but there’s not a ton of activity yet. (Maybe it’s the picture of Haibao in the header that’s driving people away?)

27

May 2010Creative Chinese Character Art

In a recent post, Deconstructing the Chinese Character Creativity of Japan, I highlighted some creative work with Chinese characters by Japanese artists. What I didn’t say at the time was, “I wish the Chinese themselves would do more stuff like this.” Well, they are, and just recently I saw some great examples of it, first sent in by reader, and then later on Kaixin Wang (China’s Facebook).

I’m not going to deconstruct them like last time, because these are just way too complex. Just keep in mind that the squares and circles framing many of them are not actually a part of the characters like they were in the Japanese designs.

25

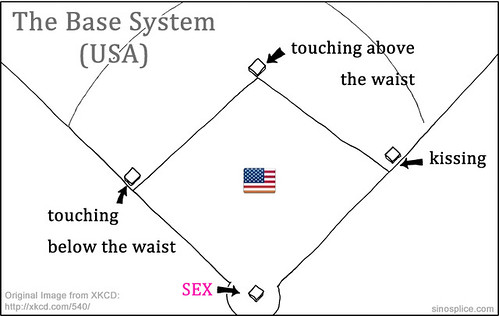

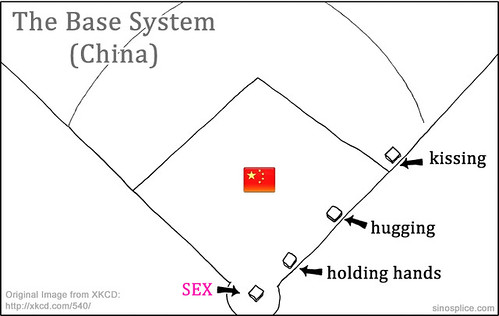

May 2010A Chinese Take on the Baseball Metaphor for Sex and Dating

Most Americans are familiar with the “base system” baseball metaphor for physical intimacy. If you’re not familiar with it, you might check out this XKCD comic for the complicated version, or this excerpt from baseball metaphors for sex from Wikipedia:

- First base is commonly understood to be any form of mouth to mouth kissing, especially open lip (“French”) kissing.

- Second base refers to tactile stimulation of the genitals over clothes, or of the female breasts.

- Third base refers to groping naked genitals (handjob or fingering), or oral sex.

- Home run (or rounding the bases, scoring a run, hitting a home run, scoring, going all the way, coming home, etc.) is the act of penetrative intercourse.

For the visual-oriented among us, here’s a graphic (adapted from XKCD’s complex version):

I can understand that a country little love for baseball might be confused by this metaphor system. Apparently even Europeans are confused by it. However, some people in China have picked it up, but in the process changed the system (reference link removed due to malware at destination website]):

- “一垒”代表拉手,

- “二垒”代表拥抱,

- “三垒”代表亲亲,

- “本垒”代表XX

Translation:

- “First base” represents holding hands,

- “Second base” represents hugging,

- “Third base” represents kissing,

- “Home” represents _____

Clearly, this is a whole ‘nother ballgame the Chinese are playing, and their playing field looks like this when superimposed onto the American field:

So much for “rounding the bases!”

Thanks to Marco from EnglishPod for bringing this interesting cultural difference to my attention!

21

May 2010Orlando Kelm on Language Power Struggles

To follow up my recent massive post on Language Power Struggles, I’d like to highlight the responses of Dr. Orlando Kelm, a professor of linguistics, teacher of many years, and learner of multiple languages. Dr. Kelm’s experience is largely with Portuguese and Spanish, but he’s also studied Japanese and Chinese, among other languages.

Dr. Kelm’s three main points were:

1. Chinese perception of use of English: There is something interesting about Chinese adoption of Putonghua as a lingua franca, despite all of the regional dialects and local languages. As related to use of English, it’s almost as if people accept their local language for personal interactions and Putonghua for official interactions. From there it is a small leap to English for professional interactions. Recently when in Beijing I visited a multinational engineering company, German-owned even, but the official language at work was English. It was amazing to see rooms full of Chinese engineers, most who had never been out of China, all using English to talk to each other at work. It certainly strengthened my understanding of the way English was perceived as a professional tool, no different in some ways from switching among c++, php, html, or java.

2. Our skewed view: My guess is that the type of person who is interested in this blog represents a minority. No doubt, most of the world probably confronts mono-lingual English speakers who assume and demand English for all communication. Our frustration with people who want to speak English with us is most likely counterbalanced with a frustrated world that feels obligated to speak English, even when they feel inadequate in doing so.

3. John asked if my experience in Latin America (with Spanish and Portuguese) was similar to his in China with Chinese. The short answer is no, not really. Indeed I have run across people who insist on practicing English with me, and from a professional end English is everywhere, but the aggressive power struggle seems less in Latin America. My guess as to why… well, first I believe that Latin Americans think that English speakers who do not speak Spanish are just unmotivated or lazy, people who could learn it if they really wanted to. On the other hand, Chinese think of their language as “more difficult”. Deep down they must think that it’s easier for them to learn English than it is for ‘us’ to learn Chinese. Add that to the items mentioned by all of these blog comments, and we see that despite John’s cool proficiency charts, language proficiency is only part of choosing which language is used.

Really interesting answers. Thanks, Dr. Kelm! (For more of Dr. Kelm’s observations, please visit his blog.)

Thank you also to all the readers that pitched in and shared your own observations. You’re certainly correct in that there are way more factors at play than I brought up in the original post. It’s been enlightening bringing it all together from so many different perspectives.

18

May 2010Language Power Struggles

The idea of the “linguistic power struggle” is one I’ve been dealing with and thinking about for a long time. I’ve made some attempts to find scholarly research on the subject, looking into discourse analysis (which is often concerned with power), expectancy violations theory, and communication accommodation theory, but so far I’ve turned up very little (even outside of Wikipedia!). Thus the discussion which follows will be mostly descriptive and anecdotal, but will raise more questions than it answers.

First, a typical example of the language power struggle. The dialog below is taken from a ChinesePod lesson aptly titled Language Power Struggle. I directed the creation of this fictional dialog two years ago, drawing on my own real experiences and those of other friends in China. The content in square brackets [like this] is a translation of the original Chinese. Note that the Chinese person speaks mostly English, while the American speaks only Chinese.

American: [Hello, can I sit here?]

Chinese: Sure, nice to meet you.

American: [I’m also really glad to meet you.]

Chinese: Your Chinese is very good.

American: [Not at all!]

Chinese: How long have you been to China?

American: [I’ve been in China for more than two years. I’m studying Chinese.]

Chinese: Oh, you are learning Chinese?

American: [I want to work in China, so I need to learn Chinese.]

Chinese: Oh. I think Chinese is very difficult for you. How do you feel this bar?

American: [It’s not bad. It’s just that nobody will speak Chinese with me, so I’m a little disappointed.]

Chinese: Ha ha! You are very serious!

American: [Because I want to practice more, so that I can learn Chinese more quickly.]

Chinese: I want to practice English. In Chinese, we say “[learn from each other]”, you know?

American: [I know. But in China we should be speaking Chinese.]

Chinese: I like talking English with you.

American: [Heh heh, then you should go to America. I came to China just to learn Chinese.]

Chinese: I want to go to America. Let’s be friends. Can you give me your mobile number?

American: [Sorry, I’ve got to go.]

The root of the conflict is quite clear: the American guy wants to speak Chinese, while the Chinese guy wants to speak English. There are quite a few issues contained within this small dialog, though. Below I’ll get into more details.

12

May 2010The Challenges Chinese Teachers Face in the USA

The worldwide boom in Chinese study has resulted in a greater demand for Chinese teachers. China is the natural supply, and thus the Chinese government is working hard to train teachers and send them abroad to teach. I’ve heard from numerous sources (including people in the Hanban, an organization which oversees the governments efforts at teaching the world Chinese) that schools are often disappointed with the Chinese teachers sent to them. American schools feel that while the teachers may know about the Chinese language, they are much too traditional in their teaching styles. They just don’t connect with American students very well.

It was interesting, then, to get the other side of the story. ChinaGeeks recently wrote about Teaching Chinese (and China) in the United States, and linked to a great New York Times article: Guest-Teaching Chinese, and Learning America. C. Custer makes some great observations, and his article is well worth a read.

Reading the NYTimes article, Ms. Zheng’s disappointment and frustration is palpable. Clearly, culture is a huge issue; the challenges faced cannot be explained away by outdated teaching methodologies.

> Still, Ms. Zheng said she believed that teachers got little respect in America.

> “This country doesn’t value teachers, and that upsets me,” she said. “Teachers don’t earn much, and this country worships making money. In China, teachers don’t earn a lot either, but it’s a very honorable career.”

And yes, there are also a few ironies in this article that anyone familiar with China will appreciate.

10

May 2010好久没写……

前阵子有几个朋友问我:为什么中文博客不写了?没错,我很久没写,而且最近的几篇都写得很简单,很短。

其实,我最初开始写中文博客的动机是:(1)锻炼写作,(2)多跟中国读者沟通交流。2005年,我初到华东师范大学读研,每个科目的老师在学期末都会要求我写论文。当时觉得写学术论文是个很大的挑战,每次都要花大量的时间才能写出看的过去的论文。(还好有中国朋友帮我修改!)后来,我渐渐觉得自己写课程论文不是那么绞尽脑汁的事了,可是此时却已经要开始准备写硕士论文了。这个挑战更大!

于是我就停止写博客了。当时的我已经受够了“锻炼写作”的乐趣了。毕业以后,由于一直要写论文,我中文已经写腻了,所以也就不想继续写中文博客了。

从毕业到现在,时间已经有两年了。这两年内我买了PS3,重新变成了游戏狂,还开了自己的公司。我想我应该休息放松够了,继而又想“锻炼写作,多跟中国读者沟通交流”了。

喂?有人还在关注我的博客吗?真是忽视你们了。但我觉得很多事情还是“放假比辞职好”。