25

Jan 2011Aeviou: A Chinese Input Method with Promise

“Aeviou” is the name of a new input method for Chinese, designed specifically for a new generation of touchscreen mobile devices with soft keyboards. This new input method, which looks to be at least partially inspired by Swype, seems to solve a lot of the problems currently faced by pinyin-centric input methods.

The Problem

The problem is that while pinyin is a convenient way to enter Chinese on a keyboard, for many, it’s an extremely unforgiving input method. For languages like English, T9 predictive text input on older phones and, more recently, auto-correct on soft keyboards have greatly sped up text input on mobile devices, but neither of these works for pinyin. This is partly due to the shortcuts offered by pinyin input methods. For example, to get 你好, you could enter “nihao” in its entirely, but you can could also enter “nih” or “nhao” or maybe even just “nh”. Most of the pinyin input methods out there now will display 你好 as a top result for any of these inputs. You quickly get used to entering “xx” (or at most “xiex”) instead of “xiexie” to get 谢谢, and the whole thing saves a lot of time.

The way this system of shortcuts is unforgiving is that it depends on every keystroke being accurate. When a single letter is used to represent a whole syllable (and thus a whole character), a typo can be disastrous. When you’re spelling out whole words in English, there’s some leeway which can be leveraged in order to create input methods like T9 and auto-correct. But when you’re shortcutting your way through pinyin, T9 and auto-correct aren’t options. (I have to admit, though, Chinese pinyin-based auto-correct would have results disastrous enough to be way funnier than the ones seen on damnyouautocorrect.com.)

Some Examples of Why You Can’t Auto-Correct

I’m going to give some hypothetical examples based on my Mac’s pinyin input system, QIM. Theoretically, you could get the same or similar results on many mobile device soft keyboards, although each is a little different. The most interesting results would probably occur on an Android phone using Google pinyin, since the input method is synced with your PC’s pinyin input method.

Anyway, the examples (in each case, there’s a typo affecting one letter in the input):

1. Trying to type “hpy” to get 好朋友 (good friend), you type “hpt” and get 很普通 (very ordinary).

2. Trying to type “bjhcz” to get 北京火车站 (Beijing Train Station), you type “bjhcx” and get 北京话出现 (Beijing dialect emerges!).

3. Trying to type “xgmn” to get 性感美女 (sexy beautiful woman), you type “xfmn” and get 幸福吗你 (are you happy?).

OK, so these examples are a little over the top, and no one is going to get by using only the first letter of every syllable to type in pinyin, but the shortcuts are built into the input method.

A New Solution

So the reason the Aeviou is a great solution is that it offers the quickness of the “shortcuts” above through a “swipe” method, made possible by a soft keyboard that updates with each “keystroke” to offer input only of possible syllables. Effectively, it kills the shortcuts but allows full, unambiguous pinyin syllable entry to become quick and painless.

Read more on TechRice, where I read about this new input method, and check out the video below for a demo:

Great idea! I’m really happy to see innovation around Android in China.

20

Jan 2011Big Snow in Shanghai

I say “big snow” because that’s the literally translation of the Chinese word for “heavy snow”: 大雪. And what we woke up to this morning in Shanghai is definitely a heavy snow for this part of China!

The Shanghainese aren’t used to the snow. This car, for example, drove out into traffic without even clearing its rear window:

Probably the weirdest thing to see, though, is the “snow sweeping”; the use of Chinese straw brooms to clear the snow. No, it’s not very effective, but no one has snow shovels.

17

Jan 2011Going to the Dentist in Shanghai

Life in China for us non-Chinese is a never-ending process of adaptation. Some things come easier than others. For me, one of the most difficult to get used to has been going to the dentist. Let’s face it — Americans are pretty vain when it comes to teeth, and we don’t see a lot on a daily basis to inspire confidence in China’s dentistry skill. Does an American like me dare go to the dentist in China? How does one make such a decision?

I don’t claim to have all the answers for everyone, but I can share my own experiences, which may be useful to some of you out there (especially those of you in Shanghai).

I started my China stay in Hangzhou. The only “dental clinics” I ever saw there were tiny little shops on the side of small roads. They often had glass sliding doors opening right into a tiny room with a dentist’s chair, and if you walked by the shop at the right time, you could peer right into a patient’s open mouth from the other side of the glass door, without even going inside. Not exactly private. Some of them also look, to put it nicely, quite “amateur,” and they offer pricing to reflect that. Clearly, they fill a need in the Chinese market, but they’re not the type of place most foreigners are going to entrust their pearly whites to.

Here’s one of the “roadside dental clinics,” this one in Shanghai, and actually looking a lot nicer than the ones I saw back in the day in Hangzhou (click through to the Flickr photo page for an explanation of the characters on the doors):

What I didn’t know at the time, living in Hangzhou, is that many Chinese people actually go to hospitals to have their dental work done. I’ve never done that, but from what I’ve heard the quality of dental work offered at hospitals can vary quite a lot, and the sheer volume of patients going through hospitals means the service is not likely to be of the same caliber as a dedicated dental clinic.

In a big city like Shanghai, western-style dental clinics do exist. They’re more expensive than more traditional Chinese options, but there are also acceptably priced options. For over 8 years in China, I had successfully avoided trying out any of these dental care options, feebly hoping that my faithful brushing and flossing would be enough to carry me through forever. Eventually, an old filling came out, and I had an undeniable need for a dentist. I ended up choosing Byer Dental Clinic (拜尔齿科) in Shanghai’s Zhongshan Park Cloud Nine (龙之梦) Shopping Center. It looked very clean, professional, and up-to-date, and respectful of patient privacy.

I was really impressed by the service and price I got from Byer Dental. Make no mistake; it was more expensive than I could have gotten from a host of more traditional Chinese options, but I actually felt at ease. I hadn’t been to a dentist in years, and it was good to see that the facilities were far more technologically advanced than anything I had seen before. The replacement filling used a high-quality white material which hardened instantly under a special blue light. The filling it replaced was from 1998, the ugly metallic green kind, that typically last less than 10 years before needing to be replaced.

I don’t remember how much I paid for my last filling, but just recently another old filling cracked, and I found myself back at Byer Dental. This time the total was 610 RMB (currently USD 93). I’m not a “member” or anything. I made the appointment the day before, was seen at 3pm on Saturday, and was completely done and out of there at 3:45pm. I could eat right away, and even though I had had a shot of local anesthetic, I guess it was just the right amount, because my mouth wasn’t even numb.

The staff is perhaps not super-fluent in English but sufficiently bilingual, and they were happy to talk to me in Chinese. I really enjoyed talking to the dentist about recent advances in dental technology, and the difference between my old crappy fillings and the new ones they put in. She taught me words like 光固化 (“photo-curing”? 光 means “light,” and “固化” means “to make solid,” as in “固体,” the word for “solid”). Really friendly and informative staff every time I go.

This recommendation is based on only two visits to Byer Dental over roughly two years, but I’ve had really great experiences there. I recommended Byer Dental to my friend Hank, and he also had a good experience there. If you’re delaying a visit to the dentist due to fear of Chinese dental clinics like I was, I recommend you give Byer Dental a try before it’s too late.

Obviously, if anyone else has any good (or bad) dental experiences in Shanghai or the rest of China, please feel free to share them in the comments. This information can have a permanent effect on other people’s lives, so please don’t hold back!

Related ChinesePod lessons:

– Elementary – Toothache

– Intermediate – Going to the Dentist

– Upper Intermediate – Straightening Teeth

– Upper Intermediate – Phobias (in which I admitted that I had been in China 6 years already, but still hadn’t gotten up the nerve to see the dentist in China!)

11

Jan 2011Three-Penis Liquor: the Perfect Gift

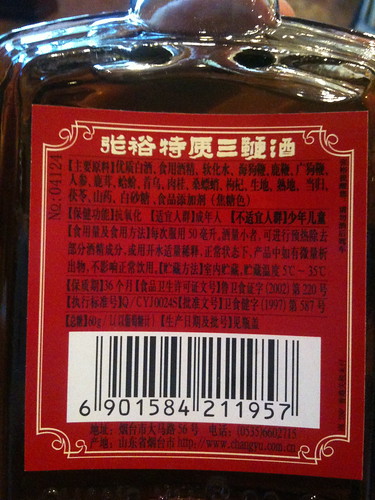

On my recent trip home, I brought a few bottles of this stuff to give to some friends:

The name of this unremarkable-looking “rice wine” is 张裕特质三鞭酒. The part to pay atention to here is “三鞭“. That means “three penis.” We’re talking various types of animal penis here, brewed in the liquor to impart vitality to the drinker. If you read the back, you can find out which three it is: 海狗鞭 (seal penis), 鹿鞭 (deer penis), and 广狗鞭 (Cantonese dog penis).

If you live in China, the character 鞭 is worth learning to recognize. It shows up a bit more often than you’d expect. “Special” liquor, “special” hot pot, Chinese medicine, etc.

The 3-penis liquor in the picture isn’t expensive, and I got it at Carrefour. When you take it home from China as a gift, remember to ask your friends to try it first, then tell them specifically what kind of special liquor it is. It’s a gift they won’t soon forget.

06

Jan 2011Stages in Learning, Adapting

I’m a pretty analytical guy. Ever since high school, when I was introduced to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, I liked the idea that we all go through the same psychological stages of development, which can be diagnosed and predicted. The Kübler-Ross “5 Stages of Grief” (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance), popularized by various movies and TV shows, also appealed to me. When studying linguistics, I learned a bit about how babies’ brains develop, as well as how certain cognitive abilities appear first, and others later. I also learned about Krashen’s Natural Order Hypothesis, which states that learners of a language can expect to master most features of a language in a predictable order, one which is “natural.” This all fascinated me.

Sure, I know that there are criticisms of Krashen’s theories, and that it’s pretty damn difficult to come up with generalities that are true enough to be meaningful. I have still felt drawn to these ideas over the years, and proposed a few similar thoughts of my own, including The 5 Stages to Learning Chinese (not entirely serious), The Process of Learning Tones (serious, if unresearched), and even touched on these ideas in my master’s thesis on foreigner’s acquisition of Mandarin tones (pretty serious). Is this useful? Yes, I think so. And I’m more and more convinced of it as I work with this stuff firsthand through AllSet.

The “natural order” propositions I’m more skeptical of are the cultural ones. The one I’m most familiar with is the Stages of Culture Shock idea (and its sequel, the Stages of Reverse Culture Shock). I’m not surprised to see a disclaimer like this preceding the stages on the Wikipedia page:

> The shock of moving to a foreign country often consists of distinct phases, though not everyone passes through these phases and not everyone is in the new culture long enough to pass through all five. There are no fixed symptoms ascribed to culture shock as each person is affected differently.

OK, everyone’s different, and every culture’s different. I get that. Your mileage may vary. Fair enough. I’m just not sure if this is useful to anyone. (Is it?)

But what if you reduced the number of variables to something more manageable? Might the validity of the generalization be improved then?

This idea came to me because over time I seem to be moving through a series of progressive “mini culture shock” stages in my trips back to the United States, and from what I’ve observed among friends and on other blogs, my experiences are pretty typical of Americans who have spent a considerable amount of time in China. These stages are spread out over a period of years, and I only notice the differences on separate trips, usually spaced at least one year apart.

Anyway, I’m just going to throw these out there. I went back through some of my old entries (2002, 2004, 2006, 2008), and there’s partial support there. But I’m curious if any readers that have been living in China a while have experienced something similar:

Stages of Cultural Response to the United States on Periodic Visits from China:

1. So Many White and Black People! (This one is typical of Americans who have lived in small-town China for a while. They can also get this reaction just from visiting Shanghai or Beijing.)

2. Americans are so fat! (This is really cliché, but it’s real. I wrote my own post on this, long ago.)

3. American air is so clean! (Pretty obvious, but perhaps less so than American obesity…)

4. America is so diverse! (I remember feeling this very acutely a few years back. It was a source of renewed pride and appreciation for my home culture.)

5. American culture is so bizarre/lame! (This is when the cultural disconnect really starts to kick in. The stars de jour, the songs, and the TV shows, are almost all unfamiliar now. It wouldn’t seem weird at all if it weren’t so unfamiliar.)

6. American food is so sweet! (I know a lot of people experience this sooner than I do, but I’m a fan of the sweets. I’m not sure if it’s just because I’m getting older, or if it’s the Chinese diet changing my tastes, but on my last visit, the sweetness everywhere was hard to take.)

Honestly, I’m not sure if there’s much universality here (especially in terms of sequence). The only one I feel strongly about is the “Americans are so fat!” stage early on. Are there any other identifiable patterns here?

31

Dec 2010A Rough End to 2010

This Sinosplice silence has gone on for too long! Time for a personal post.

Leading up to Christmas, I was preparing to make a trip back to the USA. This time that involved not only the usual gift-buying, but also getting a good lead in the recordings at ChinesePod, and also making sure that all of my AllSet Learning clients are properly taken care of the whole time as well.

What was meant to be a “short and sweet” visit was turned not so short by the massive snowfall in the northeast, canceling my flight out, and turned not so sweet by a bout of the flu. (I thought maybe the constant exposure to Chinese germs had me toughened up to the point of being nearly invulnerable to American germs, but this time I fell hard.)

It’s been a long and tiring 2010, but an enormous amount of good work has been laid for an awesome 2011. I’ve got lots more ideas for this blog, and I’ll be taking the time to write them up. (Now if only I could eat solid food…)

14

Dec 2010Chinese Christmas Videos, Chinese Christmas Songs

Well, it’s that time of year again. People are looking for Christmas songs. I try to add a little to my collection every year. This year I’ve got a couple new videos at the bottom.

Classic Christmas Songs in Chinese

Enjoy this Sinosplice Christmas music content from the archive: The Sinosplice Chinese Christmas Song Album (~40 MB)

1. Jingle Bells

2. We Wish You a Merry Christmas

3. Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

4. Silent Night

5. The First Noel

6. Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

7. What Child Is This

8. Joy to the World

9. It Came Upon a Midnight Clear

10. Jingle Bells

11. Santa Claus Is Coming to Town

12. Silent Night

13. Joy to the World

Other Christmas Fun:

– Ding Ding Dong (hilarious Hakka version MP3)

– Christmas Classics in Cantonese (the song link is still good, but the Flash links below are mostly dead now)

– The Christmas Story in Chinese (#005 and #006 in the New Testament)

Chinese Christmas Videos:

OK, this one is so ridiculous I had to share it. What happens if you put classic 90’s video games, East vs. West, racist toothpaste, and strong homosexual overtones into one little Christmas-themed Chinese commercial?

You get something like this [Youku link]:

Finally, I leave you with dancing Chinese Santas. Don’t thank me yet… [Youku link]:

09

Dec 2010The Top Ten China Myths of 2010

I rarely blog about current events, but this one is too interesting and concise to pass up: The Top Ten China Myths of 2010, by Evan Osnos of the New Yorker.

Quick and dirty list of the 10 myths:

1. Dissidents no longer matter in global diplomacy.

2. No company can afford to antagonize China.

3. China is parting ways with North Korea.

4. The U.S. has lost the green-technology race.

5. Beijing doesn’t care about air quality.

6. Beijing has licked its air-quality problem.

7. China’s G.D.P. growth speaks for itself.

8. The “Beijing Model” is a product of Deng Xiaoping’s economic engineering.

9. Apparatchiks can get away with anything.

10. China will do everything it can to avoid ruffling foreign powers.

Read the full article.

06

Dec 2010Tones in Chinese Songs

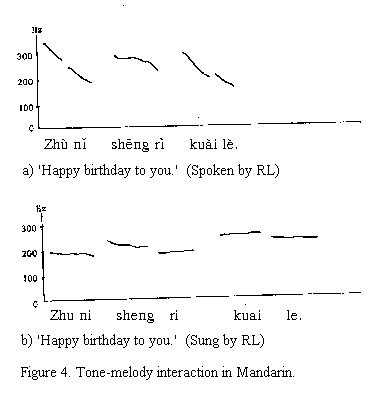

I’ve been asked a number of times: if Mandarin Chinese is a tonal language, what happens when you sing in Mandarin? Well, the answer is the melody takes over and the tones are ignored. Pretty simple.

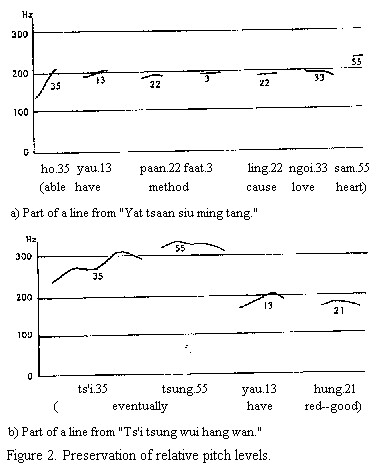

However, it may not quite end there. I recently discovered a paper called “Tone and Melody in Cantonese” which asserts that Cantonese tones are set to music in a somewhat different way:

> For Chinese, modern songs in Mandarin and Cantonese exhibit very different behaviour with respect to the extent to which the melodies affect the lexical tones. In modern Mandarin songs, the melodies dominate, so that the original tones on the lyrics seem to be completely ignored. In Cantonese songs, however, the melodies typically take the lexical tones into consideration and attempt to preserve their pitch contours and relative pitch heights.

Here’s a graphical representation of Cantonese tones, with and without music:

And here’s an example of Mandarin:

I can’t say I’m fully convinced by the pitch contour graphic that the Cantonese songs “take the lexical tones into consideration,” but it’s an interesting argument. This would suggest that studying songs would be more beneficial to acquisition of tones for the student of Cantonese than for the student of Mandarin.

If you’re interested in this kind of thing, Professor Marjorie K. M. Chan has lots of articles available on her website’s Publications page.

04

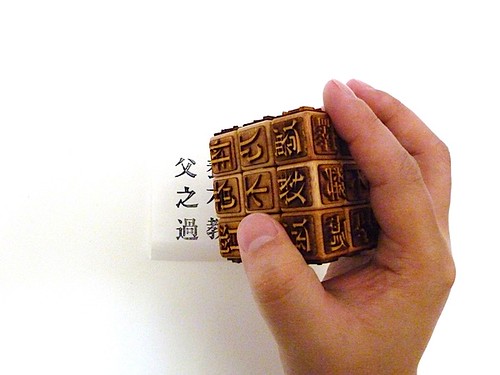

Dec 2010Rubik’s Cube with Chinese Characters

Check out this crazy rubik’s cube, refitted with Chinese characters, print-block style:

The only thing is, if you actually use ink with this thing to print characters, and then you twist it around, you’re going to end up with ink all over your hands all the time. Minor design issue, though. Cool concept!

The three-character combinations are designed to match lines from the 三字经 (Three Character Classic). Nice!

Thanks to Gaijintendo for pointing me to this. Photos from Makezine.

Update: Reader Pierre has pointed me to the blog entry by the creator of the Movable Type Cube.

30

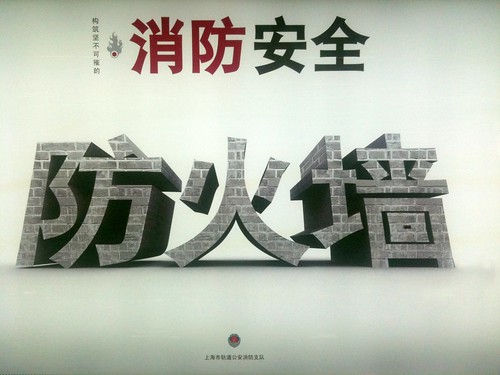

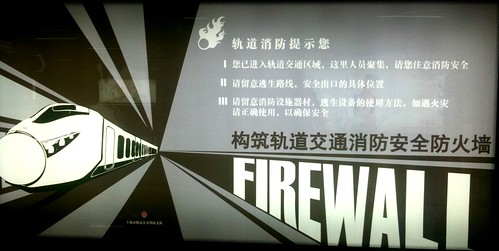

Nov 2010Subway Firewall Ads

I noticed these ads recently in the subway. They’re sponsored by the Shanghai fire department. It makes sense to want to raise fire safety awareness in light of the recent tragic fire, but I don’t really get the whole “firewall” thing. Like in English, the Chinese term 防火墙 seems to be used primarily in the IT industry these days.

P.S. My dictionary says “firewall” is another word for “Chinese wall.” Hmmm.

24

Nov 2010Writing Songs through the Expat Experience

I’m organizing an event that takes place tonight in Shanghai at Xindanwei (details here):

If you’re familiar with Tom, you know he puts a lot of thought into his songs. This talk is going to be kind of like a real-life “director’s commentary” version of a DVD, except the commentary comes after the content. Tom is going to play three different songs (one of them in Chinese) while the lyrics are displayed, and then he’ll talk about the inspiration and experiences that went into each song. Of course, he’ll also answer questions from the audience.

The event is 30 RMB, and includes drinks and snacks. Remember: it’s tonight!

22

Nov 2010Two Wishes for Chinese Language Instruction

A while back Albert of Laowai Chinese visited Shanghai. We met up for lunch and had a good chat about our experiences in China learning Chinese. He asked me an interesting question: what did I think was the biggest problem with the field of Chinese language instruction?

I told him that in general, I felt that there was way too much teaching adult foreign learners as if they were Chinese children, and I felt that more (non-Chinese) learner perspectives were needed to improve the situation. (This is one of ChinesePod‘s major strengths.)

He was looking for more specific answers, though. When pressed, I gave him these two areas:

-

Tones should be taught systematically, long-term. Way too many programs cover the tones in the first few weeks, followed by a few tone change rules, and then basically leave the students to sort the rest out. It’s not enough, and it’s irresponsible. Most students are going to need a good 1-2 years to really get a handle on the tones, so why aren’t educational institutions doing more to guide students through those frustrating times?

As I’ve said before, tones were the single most difficult part of learning Chinese for me, and I know it’s true for many other students as well. More needs to be done. We make this a major focus at AllSet Learning, but most schools really drop the ball on this one.

-

Mandarin Chinese needs a public, large-scale corpus of spoken Mandarin. There are corpora for Mandarin, but the ones that are public are not spoken Mandarin, and the corpora of spoken Mandarin are kept private and jealously guarded.

Why does Mandarin need a public, large-scale corpus of spoken Chinese? Because without it, we’re all just taking stabs in the dark as to what “high-frequency” spoken vocabulary is. Yes it is possible to objectively determine what language is high-frequency, but this requires (1) collecting lots of naturally-occurring speech samples in audio form, (2) transcribing it all. Then a proper corpus can be assembled, from which accurate, objective word counts and word frequencies can be derived.

Once that’s done, we could finally have more of a clue as to what the “high-frequency” spoken vocabulary really is. This method isn’t perfect, but it’s a big step forward from relying on native speaker intuition. And no, the new data obtained are not going to match the HSK word list you’ve got, or the Jun Da list either.

It would also be great to see a proper large-scale corpus of spoken Mandarin, balanced for regional variation. That would turn up all sorts of interesting facts, like proportion of 哪儿 to 哪里 across all regions represented, and virtually any other speech variation you can think of. (Personally, I suspect that a lot of the Beijing-hua taught in many textbooks could be reconsidered on the grounds that it simply doesn’t represent the Mandarin spoken across mainland China.)

What do you think are the biggest problems with Chinese language instruction today?

18

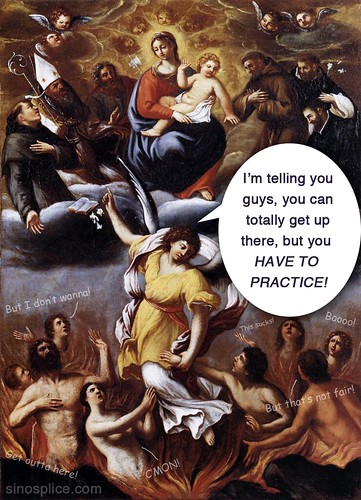

Nov 2010Tone Purgatory and Accent Exorcism

Legendary animator Chuck Jones is said to have offered budding young artists this piece of advice, in one form or another:

We all have at least 10,000 bad drawings inside of us. The sooner we get them out and onto paper, the sooner we’ll get to the good ones buried deep within.

Chuck apparently didn’t make up this quote; although the exact number varies, the advice is frequently heard in interviews with any Chouinard or CalArts graduate. This little gem has been going around for a while.

I like this idea. It’s not that you’re lacking a skill, it’s that you just need to purge all those crappy drawings inside. It’s a whole lot easier to just get rid of junk than to build something entirely new from scratch, isn’t it? You can almost imagine a “crappy drawing” count somewhere going down over time, as those amateur doodles run out and a real artist bursts forth.

This is an idea that learners of Chinese could use. It’s not that you need to “learn tones,” it’s that you have 10,000 bad tones inside you that need to get out before you can hope to be fluent. It’s a veritable exorcism of that “crazy-tones laowai accent.”

And until you expel those bad tones, they torture you a bit. It’s not enough to lock yourself up in a room and recite your textbook. Oh no, you have to get out there and talk to real people and screw up, and get those blank stares and giggles. And that does burn a little.

Until you get all those bad tones out, you’re in a sort of tone purgatory. In case you’re not familiar, purgatory is a state in which in imperfect soul is cleansed before it can continue on to heaven. Over the ages, it has frequently been depicted as purifying flames.

Every bad tone is an accent impurity, but all you can do is exorcise them slowly, one by one, by practicing your Chinese. Getting tones wrong is frustrating, and can feel like torture at times, but heaven awaits… (Heaven is, by the way, “talking to Chinese people.” Hmmm, slight exaggeration?)

So you may be in tone purgatory, but so what? You can conduct the accent exorcism on your own. You know what to expect. All you have to do is get out there and start talking.

14

Nov 2010Kingston 256 GB USB Drive (?!?)

Spotted in the electronics market at the southwest corner of Huaihai Rd. and S. Xizang Rd.:

The 256 GB drive is fake. The vendor in the electronics market admitted to me that the actual hardware was a 64 GB drive (pictured to the right). He said he wouldn’t sell a fake USB drive to foreigners like me who speak Chinese. (Get ripped off less: Another reason to learn Chinese.)

12

Nov 2010Why Learning Chinese Is Hard

I can’t agree with anyone who says that learning Chinese isn’t hard, because it’s got to be one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Sure, it’s been extremely rewarding, but I personally found it quite hard. Hopefully you’re not someone who chooses to learn a language based solely on how difficult it is perceived to be. But as someone who has chosen to learn a language for the wrong reasons before, and who also once shied away from Chinese, daunted by those terrifying tones, I can tell you that it is definitely difficult enough to scare off the casual dabbler. But what exactly is difficult about learning Chinese?

First of all, let’s get one thing straight. When I say “difficult,” what do I mean? Here’s a definition from the Oxford Dictionary of English:

needing much effort or skill to accomplish, deal with, or understand

So when we talk about difficult, we shouldn’t confuse this with time-consuming. John Biesnecker recently wrote a great post explaining why the time-consuming nature of studying Chinese does not make it difficult, followed by extensive, patient clarifications in the comments.

But John also says:

…learning Chinese is a long, drawn out series of really easy things — learn a character, learn a word, listen to a song, talk to someone, watch a movie, write an email, 等等. Not a single one of them is hard. Not one.

While I agree with most of John’s premise, I can’t agree that nothing about learning Chinese is hard. I found learning Chinese very difficult in the beginning. Although difficulty is subjective, I think there’s an important part of the equation missing here. First, two examples from my own life.

Putting in Time vs. Acquiring a Skill

When I was in high school I played a video game called Final Fantasy II. It was an RPG for the Super NES which can be beaten with the characters in your party at around level 40. Nerdy kid that I was, I loved that game so much that I continued playing it long after I had beaten it, until all my characters were up to level 99. You might call that feat silly or sad, but it was essentially a very long (but somehow enjoyable??) slog to reach increasingly higher level-up points. It was a ridiculous time investment. But one thing it certainly wasn’t is difficult.

Another example from my awkward teen years. My cousin Kevin introduced me to juggling. He insisted that anyone could learn it in one day, if they just stuck to it. After trying a few times, this seemed hard to believe. Juggling just three balls for even 10 tosses was deceptively difficult. But for some reason I dug in and kept at it. After 30 minutes I could do those 10 tosses. After an hour, I was starting to look like I could juggle three balls.

Does it seem wrong to say learning to juggle is difficult? It honestly takes less than an hour if the learner keeps at it. I’ve tried to teach quite a few people to juggle, and the conversation usually goes like this:

Learner: Wow, you can juggle?

Me: Yeah. It’s not very hard. You can learn in 30 minutes if you try.

Learner: Really? Let me try.

[I demonstrate the basics and hand over the balls. The learner takes a few tries, quickly dropping the balls.]Learner: This is harder than it looks!

Me: Yeah, but if you keep at it for 30 minutes, you’ll be able to juggle.

[5 minutes pass.]Learner: This is too hard! See ya.

So why is juggling hard, even though 30 minutes is enough to get the basics down? It’s because it requires the mastery of a new skill, which, our brain reasons, “shouldn’t be too hard.” The logic of the task is quite simple. Throw ball. Catch ball. Repeat. The brain grasps the concept immediately. But the hands do not comply. The skill is too foreign.

In essence, it’s “hard” because it’s frustrating. Actual performance does not live up to one’s reasonable expectations for one’s performance, and this is a blow to one’s ego. It’s emotional, not rational. What’s worse, if this simple task cannot be accomplished as easily as estimated, how can you be sure you’re ever going to get the hang of it?

This is the crux of the difficulty of learning juggling, Chinese, and many other worthwhile skills: the sheer frustration of the endeavor, and the ever-present fear that one is attempting the impossible. It takes a lot of effort to acquire an entirely new skill. Many people simply get discouraged and quit. “It’s too hard.”

The Hard Part

When I say that learning Chinese is hard, I don’t mean everything about it is difficult. For me, the hard part about learning Chinese, without a doubt, has been mastering the tones. The worst part was arriving in China after a year and a half of formal Mandarin study to make the horrifying discovery that no one in China understood my Chinese. I’m not one to give up easily, however, and I eventually made it. In my experience, tones are the single most frustrating thing about learning Mandarin Chinese.

Why? Well, to begin with you can’t even distinguish the tones. It seems impossible. Then, once you start to be able to distinguish them, you can’t reproduce them on your own. It seems impossible. Then, once you can produce individual tones in isolation on your own, it all falls apart when you try to string tones together. It seems impossible. Then, once you can start to string tones together with some semblance of accuracy, adding in sentence intonation screws everything up. It seems impossible.

See a pattern? Mastering tones is a long, frustrating process. I think there comes a point in almost every learner’s experience (me included!) where they say something like this:

What’s wrong with these people? I said everything perfectly. I know all my tones were right. But they always act like they can’t understand me!

This is pure frustration. It happens to every learner.

Einstein once said that the definition of insanity is “doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.” Sometimes acquiring Mandarin’s tones seems perilously close to this definition!

The Good News

The good news is that although Chinese has a steep learning curve, the worst part, by far, is right at the beginning. You have no choice but to tackle the tones right off the bat, and they’re just hard. But once you get a handle on them, the worst is behind you. (This is, however, where John Biesnecker’s “time-consuming does not mean difficult” argument kicks in, and you still have a long road ahead with the characters and vocabulary acquisition.)

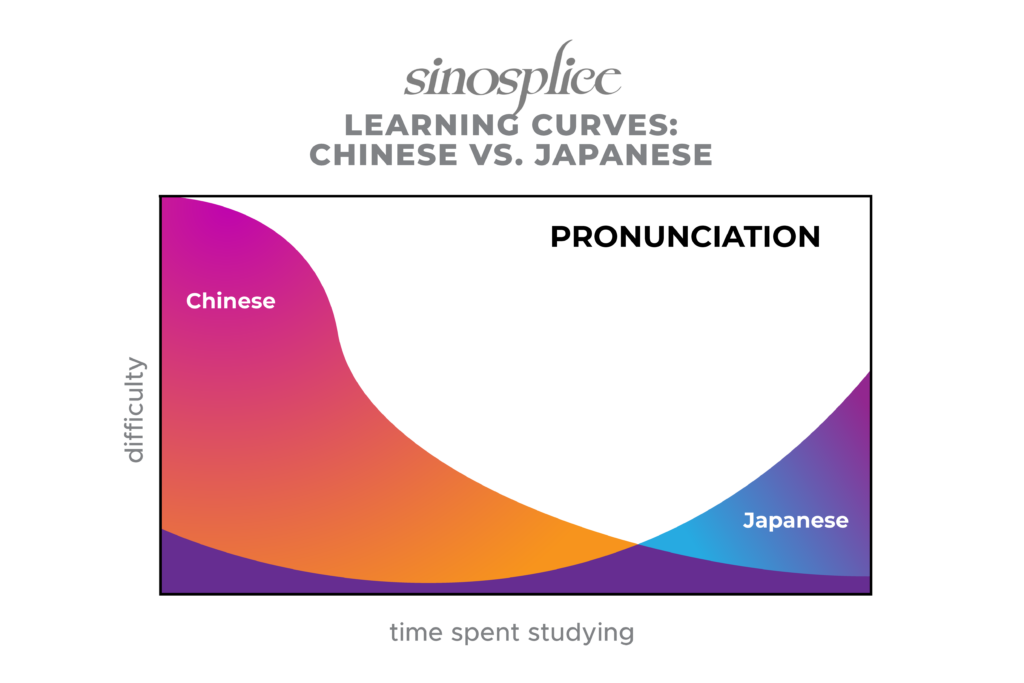

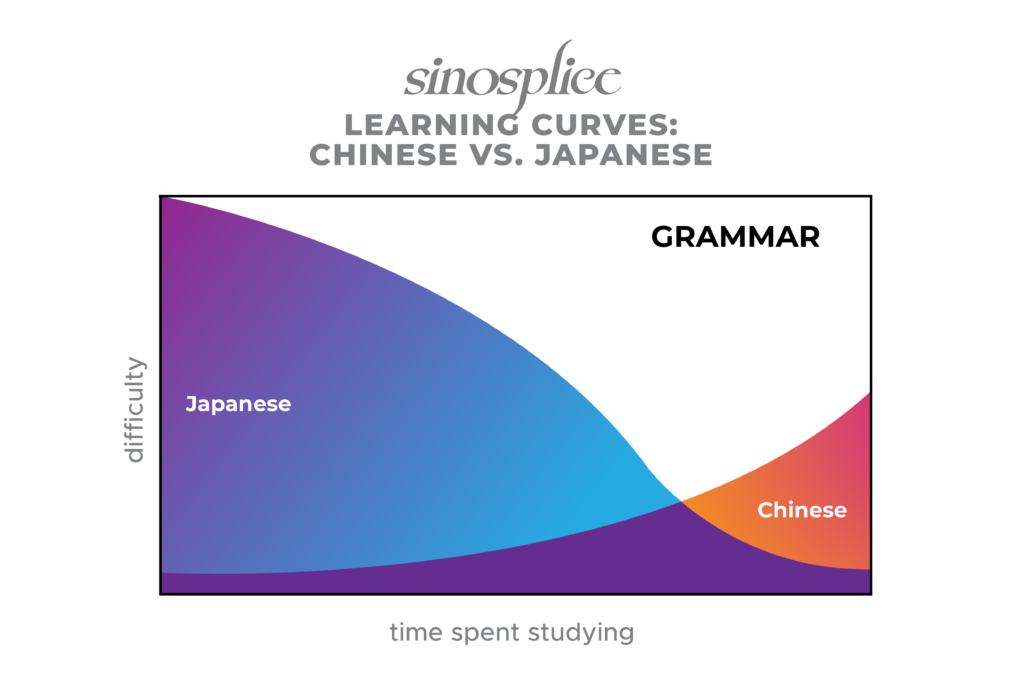

I essentially expressed this point a while back when I compared the difficulty of learning Chinese and Japanese:

Because the hardest part is right at the beginning, I think advanced learners can sometimes forget how difficult and frustrating it was. But it’s a key issue I face on an almost daily basis in my work at AllSet Learning. For beginners, the learning curve can be a bit brutal.

You’re not afraid of a challenge, are you?

Mastering tones may be difficult, and memorizing all those characters may be time-consuming, but learning Chinese is definitely worth it. Difficulty is a subjective thing, so there may be those with an uncanny knack for acquiring tones (or perhaps indefatigable, saintly patience) who honestly don’t find it difficult (or frustrating). I’m willing to bet that some learners simply have a penchant for blocking out distant painful memories, and there may even be a few out there with devious plans to trick you into falling in love with Chinese. It is, after all, one of the world’s most fascinating languages.

There have been a number of excellent articles already written on this topic. I’ve linked to some of them below. Please note that David Moser’s article is tongue-in-cheek. Brendan’s conclusion is spot on, and I think Ben Ross’s views are also very close to my own.

- Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard by David Moser

- …so, you want to learn Chinese? by Brendan O’Kane

- Journey Across the Great Hump of China: Debunking the Myth that Chinese is the World’s Most Difficult Language by Ben Ross

- How Hard Is Chinese to Learn, Really? by Albert Wolfe

- Learning Chinese: How Difficult is It? by Truett Black

- Learning Chinese isn’t hard by John Biesnecker

Relevant Sinosplice content:

10

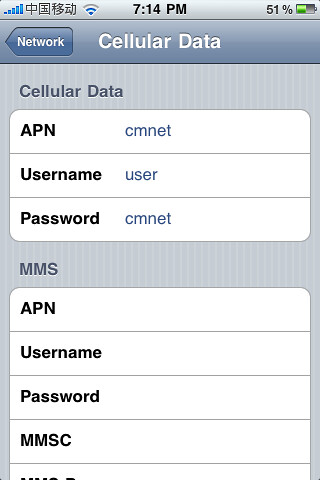

Nov 2010China Mobile GPRS Settings for the iPhone

I switched back to the iPhone lately, but since I don’t want to leave my China Mobile number, I’m stuck with the slow GPRS (Edge) cellular data connection. Anyway, somehow I always seem to have trouble finding the proper cellular data info to get everything working, and I thought I’d share it just in case anyone needs it.

First go to Settings > General > Network > Cellular Data Network and then input this data:

> APN: cmnet

> Username: user

> Password: cmnet

You don’t need to worry about the rest. Make sure that on the Settings > General > Network screen you have “Cellular Data” set to “ON.”

Obviously, you need to have already activated the cellular data service through China Mobile first for this to work.

08

Nov 2010Those Census-Confounding Chinese Tones

Recently Micah retweeted a short Chinese comedy routine [original] that was clever enough to be shared a bit more. The setup is that a census-taker asks a resident how many are in his household. Confusion ensues:

> “请问您家里是几口人?” [May I ask how many are in your household?]

> “是一口人。” [It’s one person.]

> “十一口?” [Eleven?]

> “不是十一口,而是一口人。” [Not eleven, but 1 person.]

> “二十一口?” [21?]

> “不是二十一口,其实一口人。” [Not 21. Actually, one person.]

> “七十一口?不会吧?” [71? For real?]

> “不是七十一口,就是一口人!” [Not 71. It’s just one person!]

> “九十一口?” [91?]

> “对,就是一口人。” [Right, just one person.]

OK, maybe I should have warned those of you that don’t read Chinese: the translation makes no sense in English, because the confusion is all based on tone-related misunderstandings:

– 是一 (shì yī) misunderstood as 十一 (shíyī)

– 而是一 (ér shì yī) misunderstood as 二十一 (èrshíyī)

– 其实一 (qíshí yī) misunderstood as 七十一 (qīshíyī)

– 就是一 (jiù shì yī) misunderstood as 九十一 (jiǔshíyī)

Although most of the misunderstandings above shouldn’t happen if both speakers are using standard Mandarin, I’ve witnessed quite a few cases where dialect influences tones, which, in turn, can lead to miscommunications. Personally, I find it a little comforting to know that even native speakers experience tone-related confusion, even if it’s not all that common (or comical!).

04

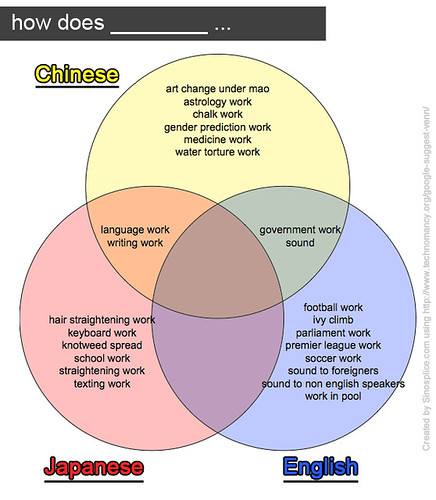

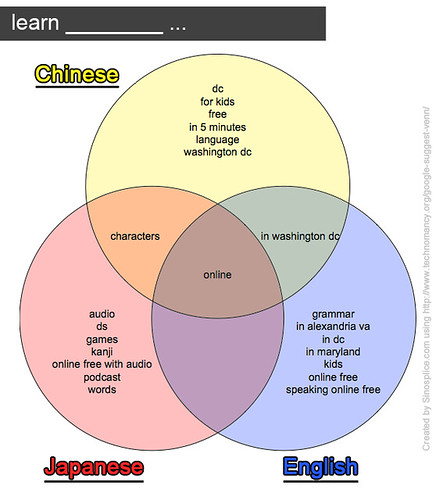

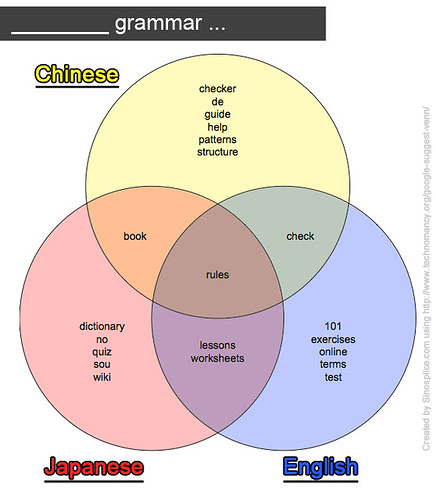

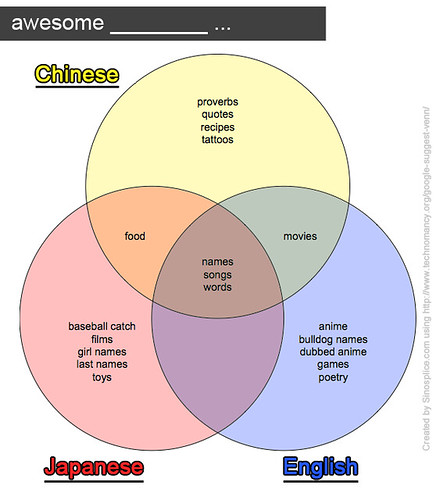

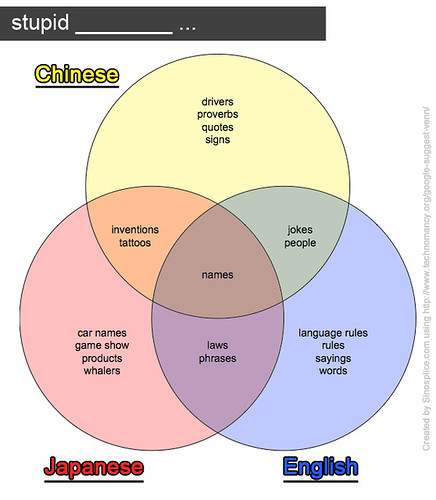

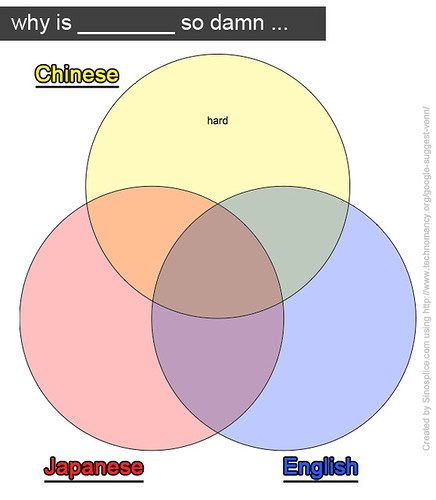

Nov 2010Google Suggest Venn Diagrams for Chinese, Japanese, and English

I was recently introduced to the awesome Google Suggest Venn Diagram Generator by Micah. Some interesting suggested searches by Google were crossed with a Venn diagram by some creative soul, and then the process was automated on the web by request. The result is a unique way to visualize and compare the data indexed by Google.

Here’s an example of what the diagram generator produces:

So we can see from this graph that according to Google, lots of people are asking (or telling) why both people and girls are mean, why girls and Americans are dumb, and why people, girls, and Americans are all stupid.

I decided to try some queries of my own. I chose the terms “Chinese,” “Japanese,” and “English” as my recurring comparisons, and then added a little color to the results. Here are some of the more interesting ones:

how does _____ …

Yikes, “how does Chinese water torture work“? Gotta love the intellectual curiosity. I like the “how does English sound to foreigners” question though.

learn _____ …

Apparently there’s a whole lot of learning going on in the DC area. It’s no surprise that people want to learn online for free, but it’s interesting that Chinese is the only language of the three that people expect to learn in 5 minutes. (Tip: it might take slightly longer than that.)

_____ grammar …

Ah, good old 的. (I’m kind of surprised it trumped 了, though.)

awesome _____ …

stupid _____ …

Why is _____ so damn…

Ah, yes. But we expected that.

01

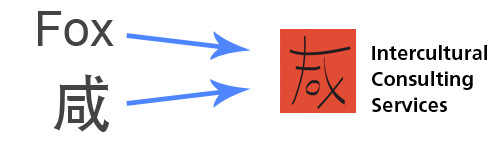

Nov 2010Fox Intercultural Consulting’s Clever Logo

I love logos that play with Chinese characters, and so I really like Fox Intercultural Consulting‘s logo. Here it is (with breakdown):

I never noticed that 咸 looks so much like the word “Fox”! Nice discovery. (Those of you that like to nitpick will notice some discrepancies, though.)

But then, isn’t it kind of weird to use a character that means “salty” for one’s company logo? It turns out that the character 咸 has quite a history, and can mean a lot more than just “salty.”

From Wenlin:

> The character 咸, from 戌 (xū) ‘destroy’ and 口 (kǒu) ‘mouth’, originally meant ‘bite’.

>> “戌 to hurt 口 with the mouth” –Karlgren.

> Then 咸 was borrowed for a word meaning ‘all, entirely’ (now rare), which happened to be pronounced the same. 咸 xián is also the name of the hexagram ䷞, variously translated as ‘Influence’ (Legge), ‘Wooing’ (Wilhelm), and ‘Cutting’ (Kerson Huang).

> The full form for xián ‘salty’ is 鹹, composed of 鹵 (lǔ) ‘salt’ and 咸 xián phonetic. 鹹 is simplified to 咸 by dropping 鹵, so now 咸 most commonly occurs as the simple form for xián ‘salty’.

More on hexagram ䷞ from Wikipedia:

> Hexagram 31 is named 咸 (xián), “Conjoining”. Other variations include “influence (wooing)” and “feelings”. Its inner trigram is ☶ (艮 gèn) bound = (山) mountain, and its outer trigram is ☱ (兌 duì) open = (澤) swamp.

So not only does 咸 represent one of the hexagrams from the I Ching, but its meaning is actually pretty relevant to Fox Intercultural Consulting’s business. Not too shabby!

With this post I’ve started using the tag “characterplay,” and also tagged previous relevant entries. Characterplay is a lot like wordplay, except that characterplay is entirely visual, whereas wordplay often relies on homophones which, when spelled out, are often quite distinct.