04

Apr 2011China in the West (in a sign)

An interesting design using the characters 西 (west) and 中 (“middle”/China):

Via Sinosplice reader Érica. Photo taken in Hong Kong.

UPDATE: The original post mistakenly had 东 (east) instead of 中 in the 西. My bad!

31

Mar 2011The 100 Most Common Chinese Surnames

Names are an important type of vocabulary. Any native speaker of English can hear a name like “Stephanie” or “Tom” or “Catherine” or “John” and instantly recognize it as a name. Knowing that a word is a name can, of course, have an important impact on listening comprehension.

In Chinese, it’s not the given names that draw from a general pool of “common names;” it’s the surnames. There is a relatively small number of surnames which the vast majority of the Chinese population uses. So knowing what the most common surnames are can come in extremely handy.

I recently discovered the website MingBa.cn (名霸), and among other name-related resources, it’s got a great page on Chinese surnames, apparently from the 百家姓. It has the top 100 at the top, followed by a huge alphabetical list of Chinese surnames, including all the obscure ones (along with pinyin!).

I didn’t like how the font was pretty small, and the top 100 didn’t have pinyin, so I created a vocabulary list for the top 100 on Sinosplice: The Top 100 Chinese Surnames. Enjoy the huge font.

Related Links:

– MingBa.cn (名霸)

– Hundred Family Surnames (百家姓), on Wikipedia

– List of common Chinese surnames, on Wikipedia (lots more info, tiny font)

28

Mar 2011Japanese Food, Chinese Characters

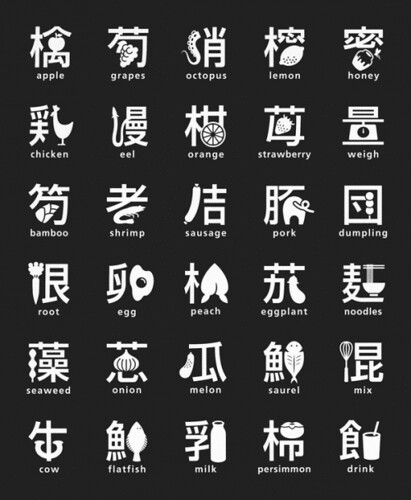

Here’s a chart which incorporates illustrations of food into their Chinese character forms [Note: these are based on Japanese kanji, so not all apply equally to Chinese; see my notes below]:

Below are the characters involved, suped up with Sinosplice Tooltips for the readings of both the Chinese and Japanese (more notes at the bottom). I get the impression the English translations were not written by a native speaker, so I’ve added a few notes in brackets to clarify where appropriate.

| English | Japanese | Chinese (traditional) | Chinese (simplified) |

| apple | 林檎 | 蘋果 | 苹果 |

| grapes | 葡萄 | 葡萄 | 葡萄 |

| octopus | 蛸 | 章魚 | 章鱼 |

| lemon | 檸檬 | 檸檬 | 柠檬 |

| honey | 蜂蜜 | 蜂蜜 | 蜂蜜 |

| chicken | 鶏肉 | 雞肉 | 鸡肉 |

| eel | 鰻 | 鰻魚 | 鳗鱼 |

| [mandarin] orange | 蜜柑 | 橘子 | 橘子 |

| strawberry | 苺 | 草莓 | 草莓 |

| weigh | 量る | 稱 (重量) | 称 (重量) |

| bamboo [shoot] | 筍 | 筍 | 笋 |

| shrimp | 蛯 ( / 老 / 蝦) | 蝦 | 虾 |

| sausage | 腹詰 | 香腸 | 香肠 |

| pork | 豚肉 | 豬肉 | 猪肉 |

| [sweet] dumpling | 団子 | 圓子 | 圆子 |

| root [= radish] | 大根 | 蘿卜 | 萝卜 |

| egg | 卵 | 雞蛋 | 鸡蛋 |

| peach | 桃 | 桃子 | 桃子 |

| eggplant | 茄(子) | 茄子 | 茄子 |

| noodles | 麺 | 麺 | 面 |

| seaweed | 海藻 | 海藻 | 海藻 |

| onion | (玉)葱 | 洋蔥 | 洋葱 |

| melon | 瓜 | 瓜 | 瓜 |

| saurel [mackerel?] | 鯵 | 鯖魚 [?] | 鲭鱼 [?] |

| mix | 混ぜる | 攪拌 | 搅拌 |

| cow | 牛 | 牛 | 牛 |

| flatfish [flounder?] | 鰈 | 鰈魚 [?] | 鲽鱼 [?] |

| milk | 牛乳 | 牛奶 | 牛奶 |

| persimmon | 柿 | 柿子 | 柿子 |

| drink | 飲み物 | 飲料 | 饮料 |

Creating this table was a good exercise in both vocab comparison between Japanese and Chinese, and also simplified and traditional characters. A few things jumped out as I created the table above:

1. Many of the Japanese characters above are not normally written in characters (kanji). In modern Japan, many words like 林檎 (apple), 苺 (strawberry), and 蛯 (shrimp) are often just written as “りんご,” “いちご,” and “えび,” respectively, in hiragana (no characters).

2. There are words like レモン (檸檬), the word for “lemon,” which looks weird not written in katakana. And I’m not familiar with 腹詰; I’ve always encountered “ソーセージ,” which entered Japanese as a loanword from the English “sausage.”

3. 苺 means “strawberry” in Japanese, but it’s the morpheme “-berry” in Chinese, used in such words as 草莓 (strawberry), 蓝莓 (blueberry), and 黑莓 (blackberry).

4. I’m not a big fish-eater, so I’m not confident in the fish translations. Any corrections are welcome.

There’s a lot more I could say here, but unfortunately, my blogging time is limited. Comments welcome!

Related Links:

– Source: Endless Simmer (via Brad)

– More Chinese Vocabulary Lists on Sinosplice

– Learning Curves for Chinese and Japanese on Sinosplice

27

Mar 2011Da Admiral’s Mandarin Un-Learning School

I subscribe to SmartShanghai‘s email newsletter, less because I try to attend all the latest events in this city, and more because the man who writes it, “Da Admiral,” is pretty hilarious.

His latest newsletter, focused on “un-learning Chinese” definitely caught my attention:

> Whenever I’m stopped on the streets, the thing I get more than anything is, “Oh Admiral, Admiral… you’re so knowledgeable and good looking and insightful about Shanghai life and society — I bet you speak perfect Mandarin!”

> My friends, I’ll let you in on a little secret:

> The opposite couldn’t be more true! I don’t speak Chinese for shit!

> And then it occurred to me… Why don’t I take my eight-years-plus experience in not speaking Chinese and share it with others? For money?

Un-learning in action, by Cris

> So I’m opening a Mandarin Un-Learning School.

> As a sort of compliment to “Mandarin Garden” or whatever it is, I’m calling it “Da Admiral’s Mandarin Post-Apocalyptic Wasteland” and we’re accepting students at all skill levels, whether you want us to rip perfect fluency in Chinese from your brain, or even if you’re looking for something a little more part-time –maybe you’d just like to reduce your vocab a bit and un-learn a few key Chinese phrases — we can help.

> Here’s the pitch:

> “Through the sweat off his brow and sheer determination, Da Admiral has maintained a near perfect and unassailable wall of incommunicability with 99% of Chinese society. Dude is still pointing at shit on the menus like a nutsack who just got off the plane, like, yesterday.

> And now he’s willing to share his secrets with you.

> For a small enrolment fee, you’ll have access to our proven tools of whittling down knowledge of Chinese to basically nil. Whether you want to take a special, personal, one-on-one, 24 hour intensive course — basically this involves about seven pounds of weed and the Complete Filmography of Nicolas Cage — or are looking to un-learn Chinese in a group setting with our special “Dog Bloopers and Various Shit on the Internet” group classes, we’ll have you not speaking Chinese in no time.”

> Are you a Mandarin un-learner on the go? Subscribe to our special Un-ChinesePod, which is basically just me screaming nonsensical phrases in made-up French to you, intermixed with the latest news on the Batman sequel. Mind-numbing stuff. Just try to retain knowledge after a few of these.

> What I’m saying here is nothing about my time in Shanghai has been more rewarding — more spiritually fulfilling — than not learning Chinese, and I feel it’s a duty at this point to share my non-knowledge with others for money.

> I’m an educator at heart. I care about my students. They’re like my family for money. And when we’re in cabs together and I see them struggling with that last — “Zho-gw-ai” or “Yoh-gw-ai” or “Ting” or whatever the fuck it is, I don’t know, you know what I mean — I feel like my job is done.

> My job is done… and a tear comes to my eye.

I’m obligated to point out here: if you’re looking for a really good one-on-one “Mandarin Un-Un-Learning” experience in Shanghai, there’s AllSet Learning. And of course, the best Un-Un-ChinesePod is ChinesePod.

26

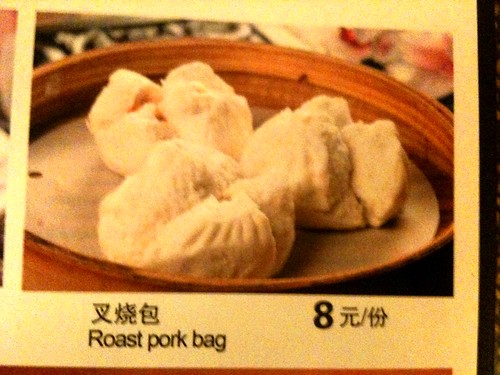

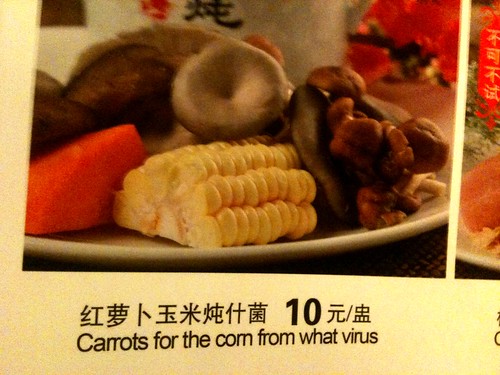

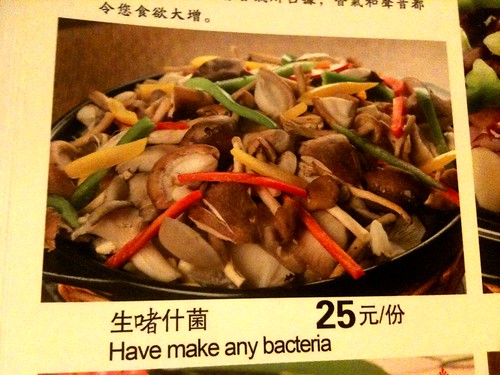

Mar 2011More Machine Translation Menu Fun

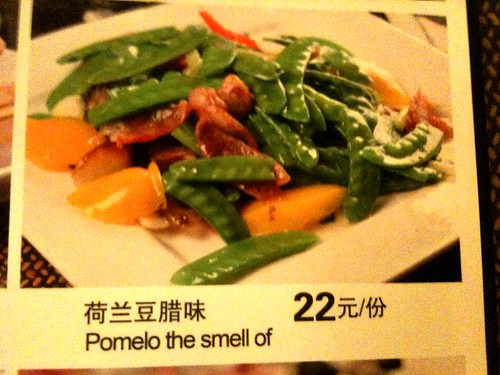

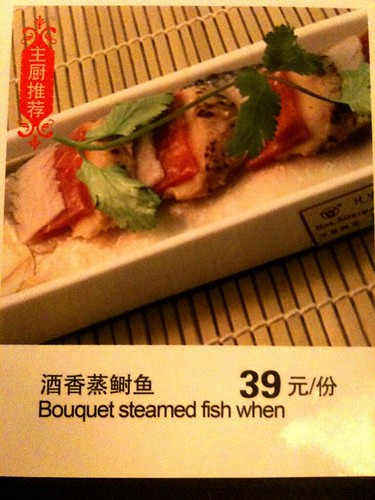

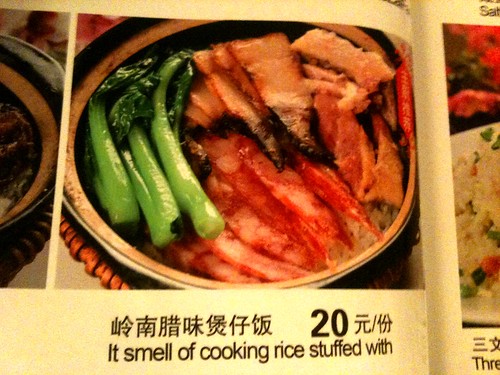

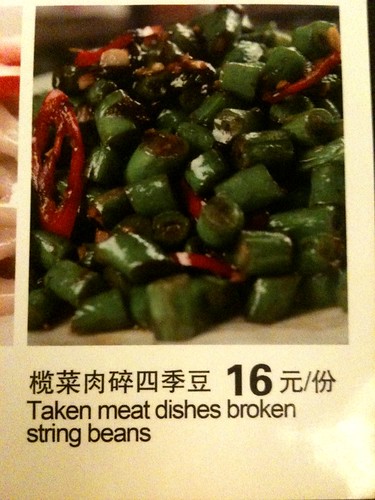

OK, I know, it’s been done before, and it’s just so easy. There are many menus in China with bad (and often hilarious) English translations. But even after all these years, this one stood out to me because (1) it is otherwise an extremely high quality menu, and (2) the errors are of a somewhat bizarre nature, rather than centering on horribly inappropriate mistranslations of the character 干 [more on that here and here].

Anyway, here are some samples (apologies for the quality!):

Where pathology and cuisine meet:

Halogen? (Another meaning of 卤)

A bunch of them have really weird endings (I think the machine translated names have been truncated):

This last one is my favorite, because it comes across almost poetic:

> taken meat

dishes broken

string beans

Indeed.

You can find more of the menu here.

Update:

In case you’re interested, the restaurant is called 炖品世家, or “Aristocratic Family of Soup.” (Oh yes, this is clearly a restaurant that has some fun with the English language!) The restaurant is in Shanghai, near the intersection of Kangding Road and Wanhangdu Road (康定路、万航渡路). A photo:

Also, a big thanks to Will, who introduced this resturant to me and provide the above photo and address.

25

Mar 2011Happy Birthday to AllSet Learning

This month my learning consultancy, AllSet Learning, turned one year old. It’s hard to believe that a year has already gone by. So much has happened in the first year, and yet there is so, so much more to be done. It’s a good feeling.

I’ve got a blog post up on the AllSet Learning blog: Year One Complete.

The service is developing quite nicely, although I’m nowhere near satisfied. Thanks to all the Sinosplice readers who have shown your support for the new business, and especially the ones that have become clients. Great things are in store for 2011.

If you’re interested in becoming a client, it’s a good time to get in touch; the number of clients I can serve at one time is limited, so I may have to start a waiting list soon.

22

Mar 2011VPNs Under Attack

How do we foreigners live in China when YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter are all blocked here? We use VPNs to get around the blocks. Five years ago, it seemed like only a few foreigners I knew in Shanghai found it really necessary to pay money to circumvent the blocks. Now, almost all foreigners I know find it necessary. Tools like Facebook have become too important of a means of communication to just give up.

For a while, it felt like there was a truce. Lots of sites will get blocked, but the blocks are easily worked around through VPNs. Those who “need” VPNs just had to pay for them. Now the situation is different. Recently many VPNs have stopped working, and even those of us that prefer to stay apolitical need to use the internet (unfettered).

Some recent articles about the status of VPNs in China:

– China tightens grip on VPN access amid pro-democracy protests, Gmail users also affected

– China Strengthens Great Firewall, While, Chinese Bypass it.

– The VPN-debate: why China’s internet censorship needs to fail

– Are all VPNs now disabled in China?

– China Tightens Censorship of Electronic Communications [Updated March 23rd]

– Fact-checking the New York Times’ China Coverage [Updated March 25th]

Are all VPNs now disabled in China? Fortunately, no. I am lucky enough to be using one of the ones that has not been affected by the recent changes to the GFW. Who knows how long that will last.

17

Mar 2011Edmund Backhouse: Decadence Mandchoue

I first started hearing about Sir Edmund Backhouse (1873-1944) years ago from Brendan O’Kane and Dave Lancashire. A “self-made sinologist,” he was apparently fluent in Chinese and quite well connected, but was also later exposed as a magnificent fraud. A prolific diarist, he also dwelled quite a bit on the sexy details of the Qing Dynasty.

Anyway, it may at times be difficult to separate the fact from the fiction in Edmund Backhouse’s story, but it’s quite a story. So I’m really looking forward to reading a new book called Decadence Mandchoue: The China Memoirs of Edmund Trelawny Backhouse, which makes a lot of Backhouse’s memoirs available for the first time. From the Amazon page:

> Published now for the first time, the controversial memoir of Sinologist Sir Edmund Backhouse, Decadence Mandchoue, provides a unique and shocking glimpse into the hidden world of China’s imperial palace with its rampant corruption, grand conspiracies and uninhibited sexuality. Backhouse was made notorious by Hugh Trevor-Roper’s 1976 bestseller Hermit of Peking, which accused Backhouse of fraudulence and forgery. This work, written shortly before the author’s death in 1943, was dismissed by Trevor-Roper as nothing more than a pornographic noveletteA” and lay for decades forgotten and unpublished in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University. Yet even the most incredible tales deserve at least a second opinion. This edition, created using a combination of the three original manuscripts held by the Bodleian, has been comprehensively annotated, fully translated and features an introduction by editor Derek Sandhaus, urging a reappraisal of Backhouse’s legacy. Alternately shocking and lyrical, Decadence Mandchoue is the masterwork of a linguistic genius; a tremendous literary achievement and a sensational account of the inner workings of the Manchu dynasty in the years before its collapse in 1911. If true, Backhouse’s chronicle completely reshapes contemporary historians’ understanding of the era, and provides an account of the Empress Dowager and her inner circle that can only be described as intimate.

Full disclosure: I’m friends with Derek Sandhaus, editor/author of the book. But that doesn’t make this book any less awesome.

15

Mar 2011Big Taste, as in “Spicy”

The other night I was enjoying a simple meal by myself in a dongbei (northeast China) restaurant. I overheard an exchange between two women and the restaurant owner. It went something like this:

> [after ordering]

> Woman: 上次点的菜太淡了,我们要味儿大一点的。 Last time our food was too bland. We want the taste to be “bigger.”

> Server: 好的。 OK.

> [the dishes are served, the women try them]

> Woman: 服务员,我们刚才说过了,我们要味儿大一点的。 Server, we just told you: we want the taste “bigger.”

> Server: 你这个“味儿大”啥意思?是说咸点,还是什么? What do you mean, “bigger?” Saltier, or what?

> Woman: 就是味儿大一点。辣点。 Bigger taste. Spicier.

> Server: 哦,你要辣一点的。我以为“味儿大”的意思就是味道浓一点。 Oh, you wanted it spicier! I thought “big taste” just meant stronger flavor.

> Woman: 不,是辣的意思。 No, it means spicy.

> Server: 那,你本来就应该说“辣点”。 Then you should have just said “spicy” in the first place…

> [The server takes the dish away to make it spicier, grumbling a bit.]

I was intrigued by this exchange for several reasons. First, neither party was from the Shanghai region, so the miscommunication couldn’t be blamed on the north-south divide that you typically see in Shanghai (like the baozi / mantou distinction). Second, the women were using an expression which, although simple, I had never heard either, and I couldn’t find listed in any of the dictionaries in Pleco (I was looking it up while eavesdropping on their conversation). And third, any time groups of Chinese people have trouble communicating, it’s interesting to me for linguistic reasons, as well as somewhat comforting, as a student who has experienced his own fair share of frustrating communication difficulties.

Also, since the word 味儿 can refer to odor as well as taste, in the absence of clear context, a more likely interpretation of 味儿大 is “strong-smelling,” or, quite possibly, “stinky.”

Anyway, after I finished my meal, I decided to go over and ask the women about the 味儿大 expression they used, where they were from, etc. They were extremely cooperative. It turns out they’re from Yichang (宜昌). I recorded the conversation, edited it down a little, and have included it for your amusement.

09

Mar 2011X is the Unknown

Do you remember “solving for x” in math class? When you first started algebra (or was it pre-algebra?), you had to learn a whole new set of methods which, when applied, could magically reveal the values of the unknown variables.

So when you saw this:

2x = 8

4x + y = 17

z(3x – 2y) = 30

…before long you could handily solve for x. And once you had x, you could solve for y. Then z was a piece of cake too.

The Algebra Connection

Chinese pronunciation is similar. We native speakers of English of English have to learn to produce some new sounds in order to become fluent speakers of Chinese. Although the pinyin “r” sound is formidable, what I’m talking about today are the sounds linguists call “alveolo-palatals“: the three Mandarin consonant sounds pinyin represents as “x,” “q,” and “j.”

So how are the sounds of Mandarin like algebra? Well, just as the in the above algebra example one would first solve for x, then solve for y, and finally solve for z, learning those “alveolo-palatals” involves a similar chain effect. Once you’ve solved for “x” (I’m talking the pinyin x here), “q” and “j” both become relatively simple. “X” is definitely the one you want to start with, though, for many reasons. X is the unknown. First solve for “x,” and “q” and “j” are within your grasp.

Why X?

There are a number of reasons to start with “x.” First of all, it’s a prominent feature of the Chinese word almost everyone learns right after “nihao” (你好). Yes, the word is “xiexie” (谢谢), the Chinese word for “thank you.”

Second, the “x” consonant contains the basic feature you need to build on to learn “q” and then “j.” Just as solving for x in the algebra equations above allows you to solve for y with a simple operation, the same is true for pinyin “x” and then “q.” Allow me to explain.

The True Nature of X, Q, and J

If you’ve studied phonetics at all, you learn IPA (the international phonetic alphabet). The main idea behind IPA is that as nearly as possible, every unique sound is represented by a unique symbol. So one good way to know if a sound in a foreign language is really equivalent to a sound in English is to check their respective IPA notations.

In English, for example, the “sh” sound isn’t actually an “s” sound plus an “h” sound. We just write it as “sh.” In reality, it’s a sound different from all the other sounds in the English language. It gets its own IPA symbol: ʃ. Makes sense, right? Now, a lot of new learners to Chinese think that pinyin “x” is the same as English’s “sh.” If that were true, the IPA symbols for the two sounds would be the same. But they’re not.

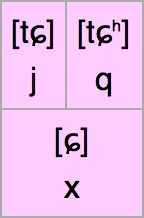

IPA for x, q, j

If there is any doubt that the pinyin “x,” “q,” and “j” sounds are foreign for speakers of English, you can look up the IPA for the sounds of Mandarin Chinese. Don’t freak out, now. The alien symbols representing pinyin’s “x,” “j,” and “q,” are, respectively, ɕ, tɕʰ, and tɕ.

Now take a look at those three consonant sounds again: ɕ, tɕʰ, tɕ. The common element is ɕ. That’s the “x” sound. This sound does not exist in English; “x” is the unknown. But the addition of the other sounds, which are not foreign to English speakers, will result in the “q” and “j” sounds.

So, once again, master that “x” sound, and you can unlock the other two. It’s practically “buy one get two free,” but you definitely have to pay for the “x,” and you may need to struggle a bit. [More info on producing this sound here.]

It’s worth it, though. Before long you’ll leave “syeh-syeh” behind and utter “xièxie” perfectly. Just solve for “x” first.

Related:

- The Sinosplice guide to the Pronunciation of Mandarin Chinese

- Wikipedia on Pinyin

- AllSet Learning, John’s own learning consultancy which serves learners in Shanghai

02

Mar 2011On Best Buy’s Departure

Recently Best Buy (百思买) announced that it’s closing its China stores. I normally don’t pay too much attention to this kind of news, but Best Buy is a little different. Somehow it felt a bit more relevant to me this time.

Best Buy is an American chain, and there’s still a huge Best Buy store down the street from where I live. I welcomed the arrival of Best Buy because I hate its domestic competitors, Suning (苏宁) and Gome (国美), which, incidentally, are also just down the street from me. I had high hopes that Best Buy would prove that the citizens of Shanghai, too, are willing to pay for better service and assurance of high quality.

Alas, it was not meant to be. It’s hard to say for sure how much of the equation is price, and how much of it is Best Buy’s failure to live up to the levels of service it upholds in North America. But something didn’t work.

I won’t say any more on the matter, though, because Adam Minter did a much better job than I ever could on his blog, Shanghai Scrap, in a post called Bye-Bye, Best Buy (China): You had it coming.

I especially liked this post because Adam shares a lot of my same sentiments. Adam notes:

> …let me note that I would have loved it if Best Buy had succeeded in China. In part, out of Minnesota pride (I’m a native, and still consider it home) but also because I liked being able to shop for electronics in China without having to bargain, worry about buying fakes, or not being able to return items. The laptop upon which I’m writing, right now, was purchased there, as was the printer to my right, the speakers in front of me, and the iPod in my gym bag. I’m as sorry, and as irritated, as anybody that this happened.

Meanwhile, business is booming at the Apple Stores across Shanghai…

24

Feb 2011МОЛОКО’s Gay Chinese Characters

Recently I was browsing Flickr photos and came across one that looked familiar:

To my surprise, I was given credit for the original idea in the photo caption.

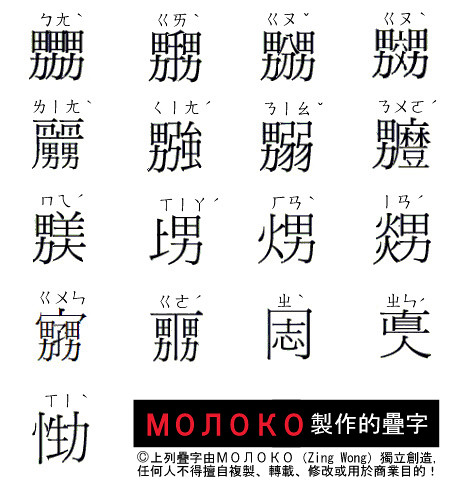

I looked at some of МОЛОКО’s other photos and discovered some “gay character creations”:

Some of these innocent-looking characters are pretty explicit if you go to the photos’ Flickr pages (click on the images) and mouse over the characters.

In case you’re not familiar, the “funny-looking symbols” next to the Chinese characters are zhuyin (注音).

22

Feb 2011Chinese Smiles

After my last two posts, my parents were complaining that my blog was all of a sudden too tech-focused to follow. Oops. So I decided to follow up with something with a bit more universal appeal: smiles!

The following photos are all from the excellent Flickr photostream of Expatriate Games, one of my favorite China photographers on Flickr. Enjoy!

More great photos are on Expatriate Games’ Flickr photostream, and also on expatriategames.net.

Smile!

19

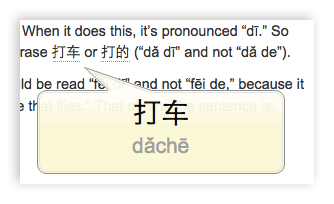

Feb 2011Sinosplice Tooltips 1.1.1

There’s a new version of the WordPress Sinosplice Tooltips plugin out. With the help of Mark Wilbur’s pinyin tone mark conversion code (see it in action on Tushuo.com), version 1.1 added the ability to convert numeral pinyin (like this: “Zhong1wen2”) to tone mark pinyin (like this: “Zhōngwén”), and add that pinyin as a tooltip to text within WordPress, producing a nice little tooltip effect on your WordPress blog or site (like this: 中文).

Installing and using the plugin is by no means difficult, but in case you’re new to WordPress, to blogging in general, or to the idea of tooltips, this is the post for you! Here I’ll just go over quickly how to install it on WordPress 3.0.5 and what exactly you need to do to produce the effects above.

16

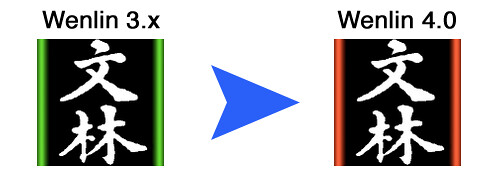

Feb 2011Wenlin 4.0 Review

I’ve been given a copy of Wenlin 4.0 for Mac by the Wenlin Institute for an honest review. It’s no secret that I’ve been a fan of Wenlin for a long time, so I’m really happy to see an update to this wonderful piece of software which most of us almost dared not hope would ever issue another update. But the day has finally come! The new version offers some very welcome updates, but one major disappointment as well.

13

Feb 2011No Smoking… in China?

China is known to be a nation of heavy smokers. So I was taken by surprise when I overheard this exchange in a beef noodle restaurant in the Cloud Nine (龙之梦) mall by Shanghai’s Zhongshan Park:

> Customer: 服务员,烟灰缸! [Waitress, (bring an) ashtray!]

> Waitress: 这里不可以吸烟。 [You can’t smoke here.]

> Customer: 有吸烟区吗? [Is there a smoking section?]

> Waitress: 没有。 [No.]

> Customer: [grumble, grumble]

In case you’re not familiar with China, let me tell you what’s surprising.

1. The guy asked for an ash tray rather than just lighting up.

2. The guy (and the other two men with him) accepted the restaurant’s no smoking policy

I guess I just like to celebrate the tiny little signs of social progress I see around me.

I’ve also noticed a sharp divide between the coffee shops in Shanghai. If you accept that the major chains here are Starbucks (星巴克), Coffee Bean (香啡缤), and UBC (上岛咖啡), they fall on a smoking/no-smoking continuum like so:

Costa Coffee aligns with Starbucks, and, at least in some locations, Cittá has recently joined the “glassed-in smoking section” faction, joining Coffee Bean.

You can see how smoking policies align with these companies’ target markets. UBC, with its dedication to universal smokers’ rights, frequently reeks of smoke, and has quite a few middle-aged Chinese men in there talking business (or something). Starbucks, on the other hand, is full of trendy young Shanghainese, and usually at least a couple foreigners. The interesting thing is that Coffee Bean and its ilk seem to have basically the same types of customers as Starbucks, and you rarely see middle-aged people there, even if they can smoke there. Most of the smokers at Coffee Bean and Cittá are young.

What does all this mean? Well, I’m just hoping that there will be less smoking in China’s future. Maybe UBC will even start to reek less!

09

Feb 2011Fat, and also Beautiful

The first part of the name of this shop qualifies for the “really simple signs” file:

The name of the store reads 胖也美服饰, literally, “fat also beautiful apparel.” This is the equivalent of a plus sizes store in the US (although, looking at the official 胖也美 website, the Chinese 胖 isn’t quite as big as the American “plus”).

To make it even clearer exactly what they’re selling, the 胖也美 website also uses the phrase 胖人服饰, which could be literally translated as “fat people apparel.”

This is one of those cases where culture makes a huge difference in translation.

06

Feb 2011Pittsburgh Left = China Left

Photo by Melissa Robison

I subscribe to the Urban Dictionary word of the day mailing list, and just yesterday I got this one:

> Making a left turn just as the light turns green, pulling out before the oncoming traffic. Most people in Pittsburgh allow and encourage this behavior.

> “That jagoff wouldn’t give me the Pittsburgh left!”

“You should honk”

Hmmm, I would have called this a “China Left.” (Usually at a major intersection in Shanghai, the first 2-3 cars in the left turn lane will try to make their turns before the incoming traffic crosses the midpoint. This is totally normal, and no one gets upset about it.)

05

Feb 2011Character Rotation Game

My friend Jason recently brought to my attention this cool logo for a band called 凶风区 (“Fierce Wind Zone”). This brought to mind a Chinese character game I proposed on my Chinese blog years ago in a post called 转字游戏 (literally, “Turn Characters Game”). I’m not sure why I never posted this stuff in English, but I figure better late than never!

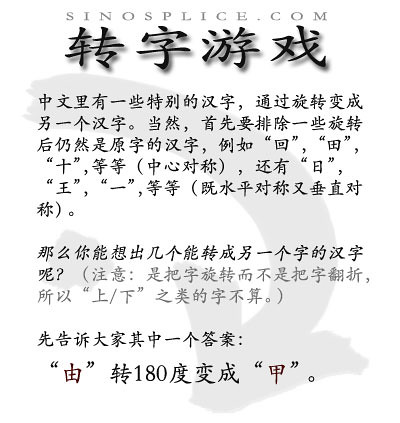

Here are the rules of the game as I originally posted them, in Chinese:

Basically, the aim of the game is to take any character and rotate it (most likely 180 or 90 degrees) to get a different character. So focusing on symmetrical characters like 田 is missing the point. The easy example I gave is the pair 由/甲.

And here are some of the solutions I provided (SPOILERS BELOW!), the second row being a bit less strict than the first row:

01

Feb 2011CNY Confusion Ahead (but also CNY Sexiness)

Chinese New Year (CNY) is this week, and it’s bound to cause confusion. This is because we’ve basically got three systems for numbering days overlapping, and quite close together:

1. The days of the week are referred to by numbers, starting with Monday (AKA “One-day”), then Tuesday (AKA “Two-day”), etc. In Chinese they’re 星期一、星期二、星期三、星期四、星期五、星期六、星期天.

2. For most of the year, dates are also referred to using the Western system. So starting Tuesday (today), it’s the first (1号). (Which is also Two-day.)

3. Since it’s CNY, everyone switches over to the lunar system for just a week or so. Day one of the lunar month (初一) is Thursday (which is Four-day, and also the third).

Sound confusing?? No, not at all. I’m a big fan of Chinese New Year.

But just to make everything clearer, you might want to check out this PDF calendar (Warning: traditional characters!). Some key vocab:

– 大年三十: Chinese New Year’s Eve

– 春节: Chinese New Year

– 初一: the first of the lunar month (never used more than around CNY)

– 初二: the second of the lunar month

– 初三: the third of the lunar month (see a pattern here?)

OK, now for the sexy part. 2011 is the year of the rabbit. (Really, I’m going somewhere with this; be patient!) I did a little searching for images on the Chinese internet and found this creative graphic:

Also, somewhat to my surprise, my innocent 兔年 (“year of the rabbit”) search turned up some rather sexy pics. The year of the rabbit only comes around once every 12 years, so I’m pretty sure it’s the first time this particular sexied-up CNY theme has appeared in mainland China (it’s referred to as 兔年美女):

And while not all of the Playboy bunny-esque photos floating around online now are actually specifically meant for Chinese New Year, the one above is, as evidenced by the golden thing in the model’s hands, which is a 金元宝 (a gold ingot, an ancient form of money which usually makes appearances in CNY decorations).

Anyway, Happy Chinese New Year.