15

Sep 2011Ode to a Paper Dictionary

The Oxford Concise English-Chinese Chinese-English Dictionary is a solid dictionary. It’s a great compromise between “comprehensive” and “portable,” and it’s the one I had with me in my early days in Hangzhou, when I had to look up every other word that I heard. I started with the “handy pocket-sized” version, but I quickly realized that even though it was half the size, it was still a little brick of paper I had to slug around, and the characters were just way too small at that size. So I used the medium-size brick of paper comfortably for years.

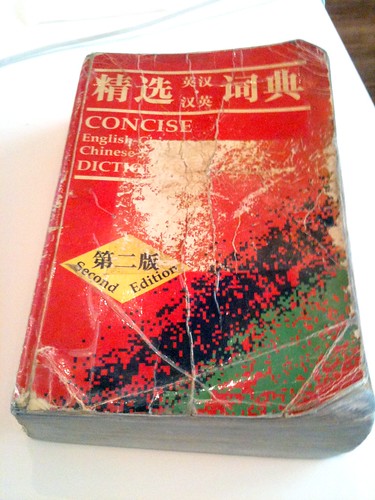

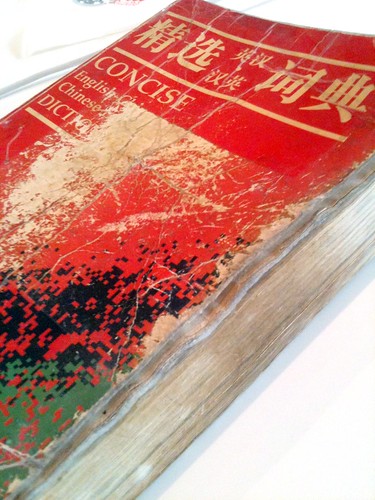

I still have that dictionary, although it’s showing its age. Over the years, I have had to use packing tape to reinforce its edges and spine, but at least I managed to do that before it started totally falling apart. Here’s what it looks like now:

Slightly worn, you might say.

When I used this dictionary regularly, I used to highlight words, phrases, and sentences that popped out at me as being useful or somehow study-worthy. What’s great is that I can still browse the dictionary now and see what I once highlighted. Sure, nothing is dated; there is no metadata. But it’s enlightening and amusing to flip through this paper record of my progress.

A little sample:

– 避免 to avoid

– 关心 be concerned about

– 关于 about; on; with regard to; concerning

– 上当 be taken in

– 下流 obscene; dirty

– 大海捞针 look for a needle in a haystack [I’m pretty sure I never ever had a chance to use this, even if I managed to memorize it briefly]

You get the idea.

But the point of this post is not to recommend a great dictionary. I used that dictionary every day for a very important period in my life, and it facilitated all sorts of conversations on a regular basis (yes, I was one of those annoying students that would occasionally put a conversation on hold if there was a word I felt I just really needed to know right away). And yet, I don’t recommend that dictionary much at all. Nowadays I regularly recommend Pleco (and sometimes Wenlin) to AllSet Learning clients, but not paper dictionaries.

Why? Well, there are a number of reasons…

– Most people don’t want to carry around a heavy book, but they take their cell phones everywhere

– Most people find looking up words in a paper dictionary quite a hassle

– Electronic dictionaries are so fast, and with one more touch you’ve saved the word as well for later reference

I remember when I first came to China, lots of people were using mini hand-held electronic dictionaries. They were great, except that (1) they rarely provided pinyin for English-Chinese lookups, and (2) they had short dictionary entries with very few sample sentences. Well, those days are over. The day has finally arrived, and entries are now bursting with information, while internet connectivity offers potentially limitless sample sentences.

So why am I still a little sad? Well, there’s definitely something to be said for idly flipping through those pages made of paper. I’m not sure why dictionary serendipity of the eyes-to-paper variety feels more special than dictionary serendipity of the search-and-related-data variety, but it does. And looking at that old battered paper dictionary, its mere existence does feel meaningful. I beat the crap out of that thing with my learning, and then did just enough work to keep it on life support. And now I neglect it, relegating it to a bathroom book, while computer-based dictionaries serve my daily needs.

We had some good times, paper dictionary. It’s not you, it’s me. But relationships change.

13

Sep 2011On Moon Cake Economics

Happy Mid-Autumn Festival, a day late. I managed to get out of eating moon cakes this year. (Whew! My moon cake eating contest days are behind me…)

Photos of Shanghai residents lining up to buy moon cakes (月饼), rain or shine (but always with umbrellas), from Jing’an Temple in the month leading up to Mid-Autumn Festival:

I’m not going to say much on economics, but this whole “moon cake economy” thing strikes me as quite interesting. While in a taxi the other night, a guest on a radio talk show made some interesting points:

1. The value of moon cake coupons has exceeded the value of the moon cakes themselves.

2. Some people eat moon cakes, but a lot of people just pass them around, gifting and regifting. (The actual quote was: “买的不吃,吃的不买,” literally, “those who buy them, don’t eat them, and those who eat them don’t buy them.”)

3. As the moon cake economy evolves, more and more products are being used as substitutes, such as ice cream moon cakes, soft mochi moon cakes, non-traditional cake as moon cakes, etc.

It’ll be interesting to see where this tradition goes in the next ten years. Will the Chinese try hard to preserve it as is, or will they morph into into something else?

Related links:

– Mooncake becomes the fruitcake of China – L.A. Times, 2011

– Mooncake economics – Global Times, 2011

– A black market for mooncakes in China – Marketplace, 2010

07

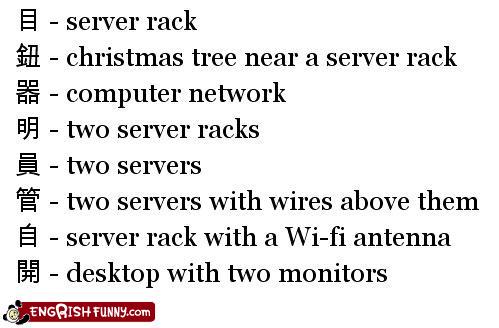

Sep 2011Chinese Characters for Servers

My friend Juan recently brought this amusing use of Chinese characters to my attention:

The characters used are:

– 目: mù

– 鈕 (simplified: 钮): niǔ

– 器: qì

– 明: míng

– 員 (simplified: 员): yuán

– 管: guǎn

– 自: zì

– 開 (simplified: 开): kāi

01

Sep 2011Pinyin Typist for iPhone, iPad

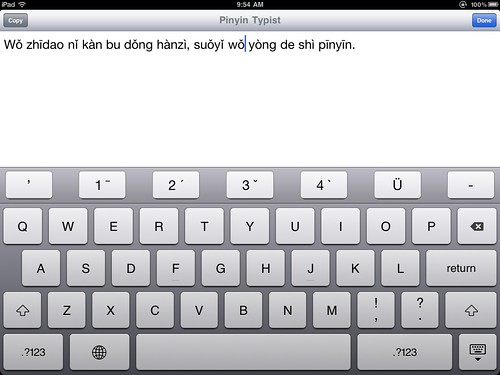

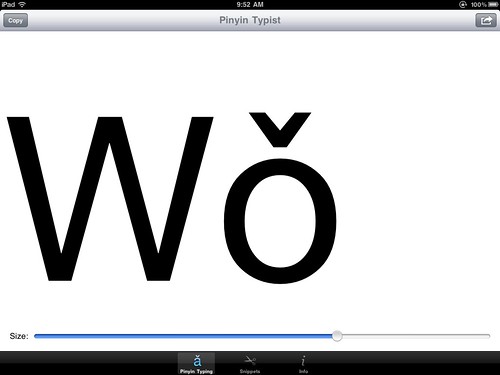

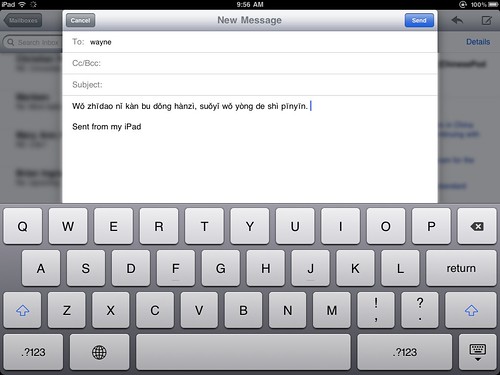

Pinyin Typist is an app for the iPhone and the iPad which allows for easy pinyin input with proper tone marks. Note that it is not an input method; you can’t use this app to switch between English and pinyin input like you can with Apple’s built-in language input support. But it turns out that Pinyin Typist works even better as an app rather than an input method.

In the screenshots below, I’ve used the iPad version of the app. Note that you can adjust size of the pinyin text (larger text makes pinyin tone marks much easier to make out). Pinyin tone input works pretty much as expected; just type out a syllable, then hit a number to add the tone mark. You can be pretty sure that tone marks are implemented correctly, because even Mark Swofford (of pinyin.info) has given it the nod. I have found no problems with it.

In case it’s not entirely clear, the way to use this app is to open Pinyin Typist, type pinyin with tone marks, then hit the app’s handy “Copy” button, switch to another app (like the “Mail” app pictured above), and paste in the pinyin.

[Update: clarification from the developer] Actually, in Pinyin Typist you can also directly email the text in its Pinyin Typing tab view, and you can also directly email the title and text of a saved snippet from its Snippets tab view, without leaving the app and switching to another one. (The button that reveals those direct emailing commands is the one on the top right.)I find switching apps to type pinyin and copy it over is actually a good way to do it, simply because I don’t use pinyin very often. Yes, I do use it occasionally, and for those occasions this app is very handy. But if the pinyin were an actual input method, it would be pretty annoying to have to cycle through it every time I wanted to switch between English and Chinese input (which is often). I had to remove Chinese handwriting input because pinyin input is almost always faster to input, and having the extra input method there in the way was just too annoying.

The one problem I have found with the app is that because I’m actually typing in English mode, iOS’s autocorrect (damn you, autocorrect!) sometimes “corrects” a pinyin syllable. This isn’t a problem when there’s a tone mark on the syllable, but it’s sometimes a problem when the syllable has a neutral tone. For example, when I typed “zhīdao” above, iOS originally correct it to “zhīSao” (no idea why). It’s a fairly minor issue, though.

The app is not free (it’s currently $2.99), which raised in interesting question for me: how important is it to be able to type pinyin on iOS? I’ll admit that I use pinyin a lot more on my regular computer than on my iPhone or iPad. I do need to frequently provide pinyin for AllSet Learning clients, but not via my iPhone or iPad. It seems like this app would be especially useful for a Chinese teacher who frequently texts students, or who sends a lot of email on an iPad or iPhone.

I raised this issue with the developer of the app, Wayne. He’s also very interested in learning more about how potential users will use his app. As a result, he volunteered to provide 5 free copies of Pinyin Typist for Sinosplice commenters who leave an insightful comment below and explain why the app will be useful to them on their iPhone, iPad, or iPod Touch. (If you have other comments about the price, you can leave those too, but be nice.) The developer will choose the 5 winners from the comments himself, and I’ll provide him with the email addresses so that he can award the app to the 5 winners (so be sure to use your real email addresses; the blog will never publicly display them).

Update: The developer has chosen the 5 winning commenters; you should be hearing from him shortly!

29

Aug 2011The Four Great Ugly Women of China

Recently ChinesePod was preparing to do a podcast on some of the “Four Greats” (四大) of China [more info in Chinese]. If you’re not familiar with any of these, you might want to listen to the podcast (it’s free). Otherwise, a quick sum-up of some of the most famous ones will suffice:

- 四大发明 (the Four Great Inventions of Ancient China)

- the compass

- paper

- gunpowder

- printing

- 四大名著 (the Four Great Classic Literary Works)

- 红楼梦 (Dream of the Red Chamber)

- 西游记 (Journey to the West)

- 三国演义 (Romance of the Three Kingdoms)

- 水浒传 (Water Margin)

- 四大美女 (the Four Great Beauties)

- 西施 (Xi Shi)

- 王昭君 (Wang Zhaojun)

- 貂蝉 (Diao Chan)

- 杨玉环 (Yang Yuhan, AKA Yang Guifei)

The funny thing is that in addition to the “Four Great Beauties” (of ancient China), there are also “Four Great Ugly Women” (who don’t seem to have their own Wikipedia page):

- 四大丑女 (the Four Great Ugly Women)

- 嫫母 (Mo Mu)

- 钟离春 (Zhong Lichun)

- 孟光 (Meng Guang)

- 阮氏 (Ruan Shi)

I talked to a ChinesePod co-worker about these famous ugly women. The conversation went something like this:

> Me: So these women were so ugly that they went down in the history books just for that? Isn’t that kind of mean?

> Her: Well, they weren’t just ugly. They also had great talent.

> Me: Well, why not just call them “the four great women of talent” then?

> Her: Well, they were also ugly.

Point taken. Cultural lesson learned!

26

Aug 2011Shanghai Internships for Learning Chinese

Today marks the end of the summer internships at AllSet Learning. We had our first intern, Donna, last summer. That was when the company was just starting out. Since we now have quite a few more clients and a whole team of teachers, there were a lot more interesting tasks for this summer’s interns, Lucas and Hugh. And their internships were pretty cool, directly related to learning Chinese.

Some of the things the AllSet Learning interns got to do:

– Take demo lessons to help evaluate different teachers’ teaching methods

– Play with “Chinese character building blocks” (a children’s educational toy set), experimenting with Chinese character constructions

– Provide feedback on various types of learning materials, from comics to Communist Party doctrine to iPad apps

– Help research and compile Chinese grammar information

– Test the effect of regular tone pair drills

– Participate in game-like components of teacher training sessions

– Play Settlers of Catan (and explain it in Chinese)

– Eat 东北菜 (pictured above)

One of the things I personally gained from having the interns around the office was a reminder of the very specific early challenges learners of Chinese face. But I also saw firsthand how the new generation of learners is coming to China much better prepared and knowledgeable. One of my interns, Hugh, even has an excellent blog on learning Chinese called East Asia Student. I’ve mentioned it before, but the days of coming to China clueless and expecting to have opportunities thrown at you really are winding down (or at least moving to China’s smaller cities).

Anyway, if you’re a bright young mind looking for an internship that offers the opportunity to learn Chinese, we’ve got them at AllSet Learning.

And finally, a sincere thank you to Lucas and Hugh for their hard work this summer. You guys were great!

23

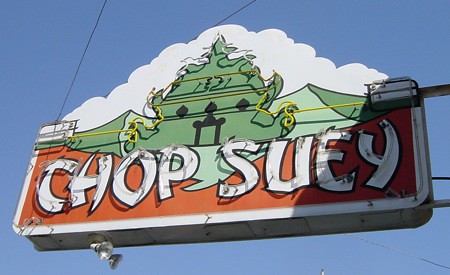

Aug 2011The Rare Chinese Font

You know “the Chinese font“? The one that just screams Oriental, because it looks like it’s made out of bamboo pieces (?), mystically arranged by a wispy-bearded kung fu master?

In case you don’t know what I’m talking about, let me remind you:

Well, the above font is one that, in my experience, you’ll be hard-pressed to find in mainland China, especially in Chinese. (Anyone out there have a different experience?) Most typed Chinese here is in one of about 4 fonts, and “Oriental” isn’t one of them. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, I suppose; the Chinese just have no reason to parody themselves.

There’s a place on the way to the AllSet office in Shanghai that actually uses the “Oriental” font, though, in Chinese. This is a rare find. Here it is:

That’s a dry cleaner’s window. The “Oriental font” is in the middle. It says, 八折价, which means “80% of the original price.”

Mystical indeed.

19

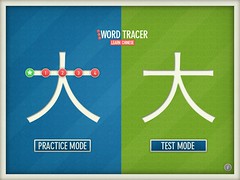

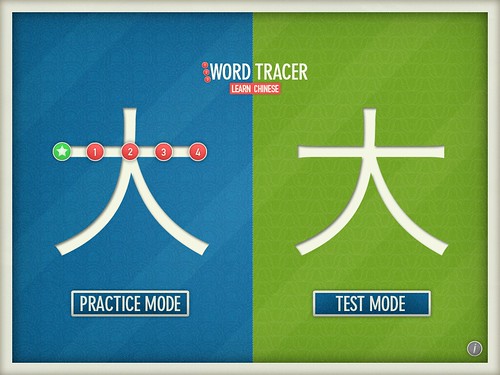

Aug 2011Word Tracer Apps for Sinosplice Readers

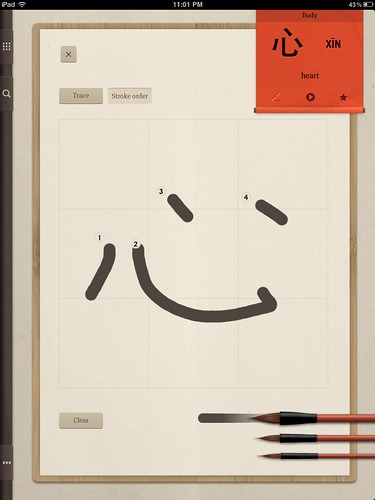

A while back when I wrote my Learning to Write Chinese Characters on the iPad post, I reviewed an iPad app called Word Tracer. Word Tracer is going strong, and now comes in both iPad and iPhone flavors. In addition, the developer has added some additional functionality to the app in a recent update, allowing for Chinese writing practice that isn’t strictly “tracing.”

Anyway, to thank me for the review, the developer has offered me a number of free copies of the app (iPad or iPhone) to distribute to Sinosplice readers. If you’re interested in getting a free copy of this app, simply leave a comment here (with your real email) or send me an email explaining why you think that the iPad (or iPhone) makes the most sense to you as a way to practice writing Chinese. I’ll award the best ones in the first 48 hours with a free copy of Word Tracer. (Be serious in your replies; I’m very interested in learning something from this!)

Update: Thanks to all of you who commented and emailed me! The response was really pretty good, and I regret that there are too many of you for everyone to get a free copy of the app. I do appreciate the responses, though, and those selected will receive an email shortly. I’m closing comments on this blog post now.

16

Aug 2011The Three De Song

Learners of Chinese confront the “de triple threat” of Chinese structural particles pretty early on. You see, there are three different characters to write what sounds exactly the same to the ear. The three characters are 的, 得, and 地, each pronounced “de” (neutral tone) when serving as a structural particle.

If you’re just trying to improve your listening and speaking, you don’t really need to worry about this issue. If you’re working on your writing, however, you’re going to want to get it straight. I found the following (simplified) approach helpful:

- …的 + Noun

- Verb + 得…

- …地 + Verb

OK, yes, it leaves out a lot of special cases, and the aforementioned “Verb” in “Verb + 得” can also be an adjective. But they’re nice rules of thumb if you’re looking for something a bit simpler.

But here’s the interesting thing: because the issue of the three de’s is one concerning writing and not speaking, Chinese native speakers themselves have to learn these rules, and can sometimes get tripped up. Some people who don’t need to write for a living might even just “opt out” of the whole issue and use 的 exclusively.

But because Chinese children have to learn to use the proper “de” in school, there is actually a children’s song about the three de’s! [source]

> 《的地得》 儿歌

> 左边白,右边勺,名词跟在后面跑。

美丽的花儿绽笑脸,青青的草儿弯下腰,

清清的河水向东流,蓝蓝的天上白云飘,

暖暖的风儿轻轻吹,绿绿的树叶把头摇,

小小的鱼儿水中游,红红的太阳当空照,

> 左边土,右边也,地字站在动词前,

认真地做操不马虎,专心地上课不大意,

大声地朗读不害羞,从容地走路不着急,

痛快地玩耍来放松,用心地思考解难题,

勤奋地学习要积极,辛勤地劳动花力气,

> 左边两人就使得,形容词前要用得,

兔子兔子跑得快,乌龟乌龟爬得慢,

青青竹子长得快,参天大树长得慢,

清晨锻炼起得早,加班加点睡得晚,

欢乐时光过得快,考试题目出得难。

I find the explanation of 得 a bit suspect. It “comes before adjectives”? Kinda misleading (but then again, so is “after verbs”).

I tried to find an online video of this song, and instead found a very similar but different song also about the three de’s:

The amusing thing about this video is that in at least one place, the subtitles get the “de” wrong. (Can you find it?)

05

Aug 2011Continent Names and Region Names in Chinese

Although not actually very complicated, the names of continents and world regions can trip up a student of Chinese. It’s not the continent names that are hard, it’s that knowing the continent names can lead one to incorrect inferences about the names of various world regions. An AllSet Learning client (this is for you, Stavros!) recently reminded me of this fact. I struggled with this myself not so long ago. Because no one ever took the time to lay it out for me, it took me forever to piece it together on my own.

Basically, the way it works in Chinese is like this:

1. If it’s a continent, it ends with the suffix –洲. (You can think of 洲 as representing the meaning “the continent of….”)

2. If it’s not a whole continent you’re talking about, drop the 洲.

So that means, for example, that “Western Europe” is not ×西欧洲, because it wouldn’t make sense to say “the continent of Western Europe.” Drop the 洲, and you get 西欧, the correct way to say “Western Europe.” It’s as easy as that. (I say “easy,” but I know I said ×西欧洲 quite a few times before anyone ever told me, “we never say that; just say 西欧.”)

These examples below should help drive the point home:

- 亚洲 – Asia

- 东亚 – East Asia

- 东南亚 – Southeast Asia

- 中东 – the Middle East

- 欧洲 – Europe

- 北欧 – Northern Europe

- 西欧 – Western Europe

- 东欧 – Eastern Europe

- 非洲 – Africa

- 北非 – Northern Africa

- 南非 – South Africa (the country)

- 西非 – West Africa

- 东非 – East Africa

- 澳洲 – Australia

- 南极洲 – Antarctica (literally, “South Pole Continent”)

- 北美洲 – North America

- 南美洲 – South America

A couple final complications…

1. You don’t often divide either Antarctica or Australia into regions in Chinese

2. You can also say 美洲, which means something like “the Americas”

3. Because 北美洲 and 南美洲 already have cardinal directions built into their names, it’s awkward to try to use the short form (like ×东北美 or something).

So the world region names are actually pretty simple, no 洲ke…

03

Aug 2011What can save this country?

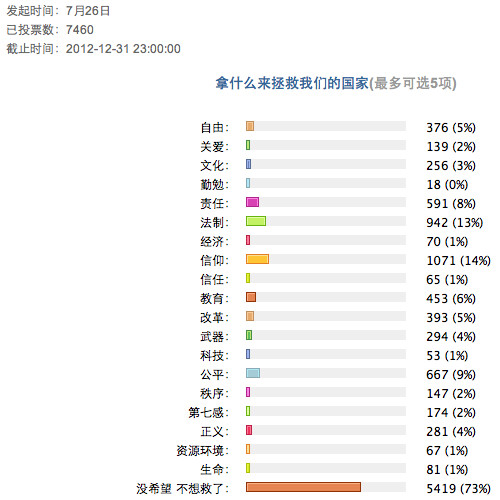

In the wake of China’s recent bullet train disaster, I came across this poll on 开心网 (kaixin001.com):

Transcription:

拿什么来拯救我们的国家? (最多可选5项)

- 自由

- 关爱

- 文化

- 勤勉

- 责任

- 法制

- 经济

- 信仰

- 信任

- 教育

- 改革

- 武器

- 科技

- 公平

- 秩序

- 第七感

- 正义

- 资源环境

- 生命

- 没希望 不想救了

Translation:

What can save our country? (choose no more than 5)

- freedom

- love

- culture

- diligence

- responsibility

- law

- economics

- faith

- education

- reform

- weapons

- technology

- fairness

- order

- the 7th sense

- justice

- natural resources

- life

- there’s no hope; don’t want to save it

In case you missed it in the original image, 73% of respondents (over 5000 in total), most of whom are young people, chose the final answer.

It’s not an easy time to be Chinese.

27

Jul 2011Thoughts on an American Job Applicant on Chinese TV

I’ve mentioned before that I occasionally indulge in the Chinese dating show 非诚勿扰. There’s another one of these reality TV-type Chinese shows that I watch from time to time called 非你莫属 (English name: “Only You”). On this show, each entrant is a job applicant given a chance to explain the type of job he’s looking for and interview with a panel of 12 bosses right there on camera. If all goes well, the bosses make offers to the applicant, and details of salary are discussed right on the show. Finally, the applicant is given a chance to accept the final offers or decline them and leave the stage.

This show is appealing for a number of reasons. There is quite a range of applicants, from young kids with no experience, to senior citizens, to the destitute and desperate, to the physically abnormal. Quite a few of the applicants just plain don’t have much to offer. The “bosses,” who are on the show to promote their own companies, can also say some interesting things. Perhaps one of the most compelling aspects to me is seeing what kind of job offers are made on the show, and what salaries the applicants will accept.

After watching this show for a while, I was surprised to see recently that there was a young American applicant. Unlike 非诚勿扰 (the dating show), which has had quite a few foreigners on the show, I’d never seen it on this show. The applicant was a 25-year-old white American male named Nathan (Chinese name: 尚德). Having lived in Beijing for a while, Nathan spoke pretty solid Chinese, and had no major issues communicating on the show. But the bosses’ reactions to Nathan were not quite what I expected.

Before I go on, some links are in order:

* A Sohu TV link to the video (the segment discussed here is 01:06-16:05)

* A Google Docs link to the Chinese transcript (01:06-16:05)

24

Jul 20112011 Update for Sinosplice

The Sinosplice blog has recently undergone a few minor upgrades, including:

1. Vastly improved search. (It was terrible before. I myself used to use Google to find content on my own site.)

2. Social sharing icons. (I tried to avoid this for quite a while, but it’s a trend that won’t be ignored! My reward for waiting was being able to include G+ easily.)

3. Automated related post info. (I’ve been meaning to do this for a long time. Scroll down on a post or page to see related posts, NYTimes-style.)

4. iPhone optimization for cell phone viewing.

5. Tiny style tweaks.

Please let me know if anything doesn’t sem to be working right for you. You may need to clear your cache and/or reload the page a few times.

Thanks to Ryan from Dao by Design for once again doing a great job and being so easy to work with.

21

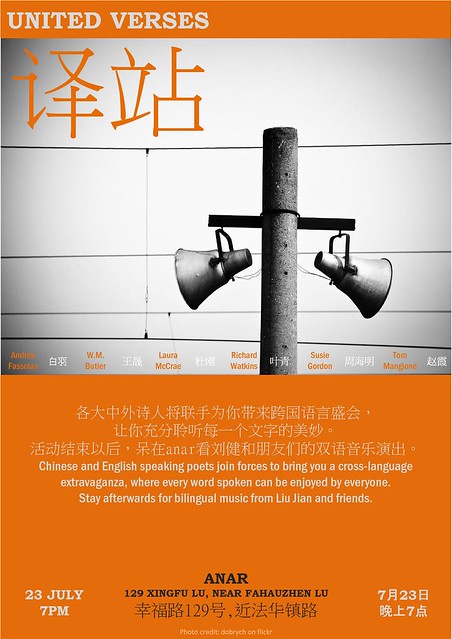

Jul 2011United Verses

My friend Tom (mentioned once before here) has put together a really cool event which he’s calling “United Verses” (译站 in Chinese). The concept is basically a bilingual poetry reading event. Each Chinese poet will read his poems in Chinese, and then an English-speaking partner poet will read English translations of them. That English-speaking poet will later read his own poems, and his partner poet will read the Chinese translations.

This is a really cool cross-cultural activity, and I applaud Tom for putting it together. It took a lot of work to coordinate translators behind the scenes, because the poets themselves aren’t usually the translators. Additional translators are needed, both native Chinese speakers and native English speakers.

I participated as a translator myself (as did one of my AllSet Learning clients), and I found it a really interesting and rewarding experience. Not only do you get to discuss the meaning behind the poem with the original poet, but then you also get to discuss your translation into English with an English-speaking poet. This isn’t just basic off-the-cuff translation, and the resulting translations are quite solid.

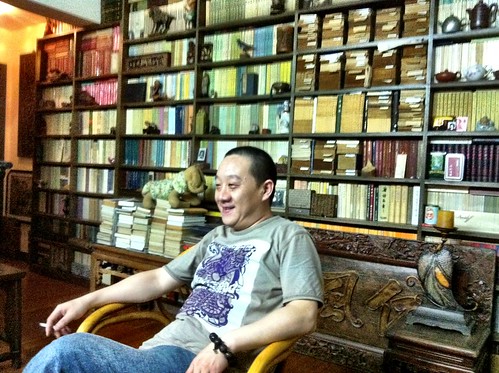

Unfortunately I won’t be able to be at the event myself, because I’ll be out of town. I leave you with a photo of “my poet,” 叶青, a very interesting Shanghainese man, pictured here in his study.

Finally, the event details in plain text:

> United Verses (译站)

> July 23rd, Saturday 7pm (event starts around 8pm, but seats are limited)

> at Anar: 129 Xingfu Lu, near Fahuazhen Lu (幸福路129号,近法华镇路)

14

Jul 2011I miss Best Buy

The other day I went to Chinese electronics retail giant Suning (苏宁) to pick up a new USB drive. I’ve never been impressed by either Suning or Gome (国美), but my most recent visit made me wonder if with Best Buy’s recent closing, they’ve just kicked back and completely stopped trying altogether.

I was looking at Sandisk’s USB drives, eyeing the 8 GB one, and then I noticed an equally compact 16 GB version. I asked the price, which wasn’t listed. The exact same model 16 GB drive was quite a bit more than twice the price of the 8 GB model. Hoping against hope, I asked if this wasn’t a little strange (check here for an example of normal pricing on Amazon), and that if she might have gotten the price wrong. I forget what the salesperson said, exactly, but the message was clear: “I think you’re confusing me with someone who gives a damn.”

Anyway, I decided to go with the 8 GB version, but I forgot that I wasn’t at Best Buy anymore. I couldn’t take my selection to checkout, I had to take a special number to the far side of the store to make my payment in a carefully hidden location. But the amusing thing was that my order number was not printed out, or even handwritten on a standard form. No, it was scrawled on a random scrap of paper. Classy.

Anyway, I found the cashier in a desolate corner of the store and made my payment. (Apparently the number wasn’t made up, at least.) I located the original salesperson, wondering where my purchase was. She had cast it aside on a random shelf under some earphones. She retrieved it for me. I asked for a bag. Sorry, no bags.

So, walking towards the exit with my unbagged purchase, I wondered how I looked any different from a shoplifter just making off with an item plucked from the shelves. Many Chinese stores that use the “cashier all the way across the store and nowhere near the exit” system have a guard at the exit who checks for a receipt. At Suning, there were no guards, no employees in sight. Just a big wide swath of apathy pointing the way out.

Yeah, I must admit that I miss Best Buy. I still think “service” is a good idea.

12

Jul 2011Z-ZH Wordplay

I’m wondering if this ad would be as likely to be used in northern China:

The text of the ad is:

> 招租!找主!

The pinyin for the ad is:

> Zhāozū! Zhǎo zhǔ!

If you ignore both tones and the z/zh distinction (which a lot of southerners–especially elder southerners–do frequently), you get this:

> Zao zu! Zao zu!

The meaning of the ad is something like, “For rent! Seeking the right person!” (“主,” often meaning “host” or “owner” is a bit tricky to translate, because normally someone in a position to rent is not a “主,” but in this case that’s who it refers to: the appropriate party to do the renting.)

07

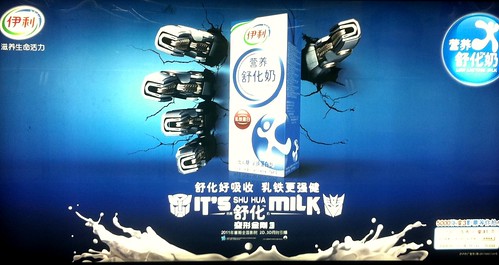

Jul 2011Transformers and… Milk?

With the movie Transformers 3 now out, Transformers are popping up in Chinese media more too. The other day I snapped these pictures of an ad campaign involving 舒化 milk. (Sorry the photos are blurry… I have yet to figure out the best way to consistently get clear photos of back-lit subway ads with my cell phone.)

OK, kids like Transformers, kids drink milk. Still, badass robots drinking milk? It seems kinda off. (Stop messing with my childhood memories!)

04

Jul 2011Please speak Mandarin (or laugh at me)

Quite a while ago I made a shirt which had 请讲普通话 (“Please speak (standard) Mandarin”) on the front, and started selling it on the Sinosplice store (through CafePress). The idea is that if you challenge the people around you to talk to you in Chinese, they probably will. It wasn’t until my last visit to the States in February that I was able to pick up my own “Please speak Mandarin” t-shirt, and not until the weather warmed up recently that I was actually able to see the effect.

The first time I used it was in a cafe, where the waiter insisted on talking to me in English, even though I initiated in Chinese. It was a classic language power struggle. I pointed to my shirt and asked him to 请讲普通话, which was incredibly awkward for me to do. He then got it, but clearly found it extremely difficult to not use English with a foreigner.

Later in the day, I caught several girls reading my shirt, laughing, and pointing it out to their friends. They didn’t talk to me.

So, it’s only been Day 1 of the experiment, but so far empirical evidence suggests that this shirt may be amusing to Chinese girls. (My wife, on the other hand, found it a little embarrassing.)

Related: Other Sinosplice original t-shirts

30

Jun 2011Learning to Write Chinese Characters on the iPad

One of the reasons I rushed to get an iPad for my own company is that the iPad is the leading tablet computer device, and tablet computers, with their relatively large touch-driven screens, seem uniquely poised to offer a great learning experience for a new generation of learners. Now that the iPad has been out for a year, developers have had some time to dig into iOS and create some cool apps for learning to write Chinese characters.

The only problem is that they haven’t yet. It’s not that they haven’t done anything, it’s just that no major player with a lot of resources has put a lot of effort into creating a superior app just for teaching writing. Significant effort has gone into Pleco‘s iOS handwriting recognition and OCR function, but neither of these teaches writing.

Before I go into my reviews of the handful of Chinese writing apps I found, I should first pose a question: what should an app that teaches Chinese characters do? This is a question that at times seems neglected by app creators. It’s easier to focus on what can be done with an app, rather than what needs to be done for real learning.

To effectively teach the writing of Chinese characters in a comprehensive way, an app would need to do the following:

1. Introduce the basic strokes, emphasizing the direction in which each is written and the shape of each.

2. Introduce the building blocks of Chinese characters, calling attention to how they function is a part of a whole.

3. Introduce the various structural types exhibited by Chinese characters, and the order in which characters’ various component parts should be written.

4. Introduce new characters in a progressive way, building on what has come before, while still trying to stick to useful characters as much as possible.

5. Provide practice writing the characters and give feedback.

This issue goes way beyond the scope of this blog post, but the point is that most of the apps out there now stick mainly to #5. Because most of the apps are largely about practicing writing, I’m going to talk mostly about the concepts of tracing and feedback. Now onto the reviews…

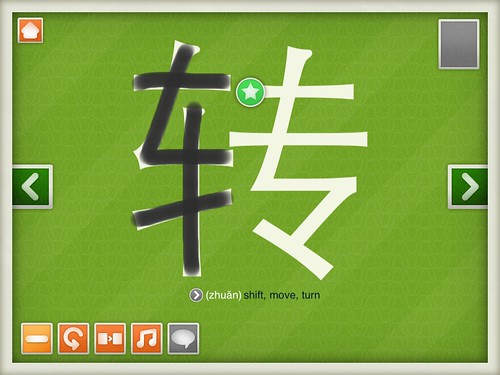

Word Tracer

Price: $4.99

| Feature | Description |

| Tracing | Yes (it’s in the name!) |

| Feedback | Yes, a green star tells you where to start writing when you go off track. You’re not allowed to write incorrect strokes. |

| Free-form writing | No; tracing only |

Word Tracer is a very polished app. It’s attractive and was clearly crafted with care. The issue of stroke direction takes center stage in this app, as a star in a green circle tells you where to start, and a series of numbers in little circles show you which way to make the strokes.

While the app is not a course in characters (which would need to go through numbers 1-4 I outlined above), it does offer a nice collection of characters to choose from, ranging from a frequency list to common phrases. I missed this feature at first, and it definitely adds a lot.

Overall, the app shows a lot of attention to detail. It wasn’t created to be a writing course, so it’s mainly a polished “writing practice app,” and its name very clearly states what this app is all about: tracing. It can’t help you with recalling characters without any prompt and writing them out.

On the plus side, I actually met with the main developer in Shanghai, and he seems quite open to suggestions for improvement, and has plans to make the app better. (Full disclosure: the developer let me try out this app for free.)

If you’ve already learned how to write characters and are looking for a mechanical way to practice writing on your iPad, this app is not a bad choice.

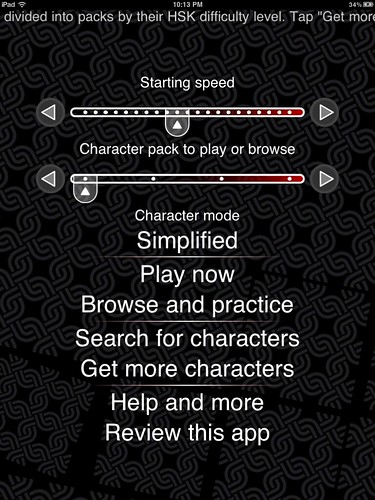

trainchinese Chinese Writer

Price: Free (for the basic app)

| Feature | Description |

| Tracing | Yes, in game form |

| Feedback | Yes, a big red “X” tells you when you make a mistake but gives you no immediate clue where you went wrong. You’re not allowed to write incorrect strokes. |

| Free-form writing | No; tracing only |

I really like that this app tries to be a game. It’s not the most fun game in the world, but I’ve seen more than one learner really get into it. The timed aspect also adds another dimension which makes the “trace the strokes” mechanic a bit less monotonous (at least for a while). I also like the options in the beginning (although that screen with its crazy animated background is a little busy).

The way the game works is that characters slowly drop for the top of the screen. You tap them once to zoom in, then quickly trace over them to “destroy” them. That’s it. If you can write a character especially fast, you are praised with a “很快” (“very fast”). If you’re too slow or keep getting the strokes wrong, the character eventually drops off the bottom of the screen, and that’s one strike against you.

One of the best things about the app is that at the end, after you’ve gotten your 5 wrong characters and the game is over, the game shows you which characters you got right and which you got wrong, and then you can review the correct stroke order for the ones you got wrong. The app is never especially clear about the direction of strokes, however.

In the end, it’s tracing only, and the characters are chosen at random. The app is solid, though, and it’s free. Not bad for basic mechanical writing practice.

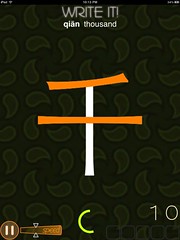

Chinese Writer for iPad

Price: Free (tutorial only; additional account required for other functionality)

| Feature | Description |

| Tracing | No |

| Feedback | Yes, the correct stroke flashes on the screen when you make a mistake. You’re not allowed to write incorrect strokes. |

| Free-form writing | No |

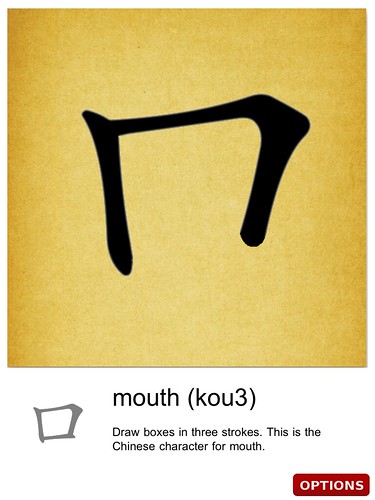

Chinese Writer sets itself apart in that it is not a tracing app. It’s slightly confusing at first, because (1) the app button is labeled “ChinesePad,” and (2) it seems like you have to sign up for a Popup Chinese account to use the app, since neither the simplified or traditional “practice mode” seem to do anything. Apparently only the “tutorial mode” is available if you don’t have a subscription (that button works).

As you write each stroke, the app shows your stroke in red, but it doesn’t actually save it on the screen; it either accepts it as “correct” and replaces it with a print-style version of the stroke, or it rejects it and erases it, flashing the correct stroke in the correct place to prompt you.

In theory, the app is fine, sort of a simpler version of the Skritter system. It can be confusing, though, rejecting seemingly perfect strokes, and rejecting quite imperfect ones.

The app is free, and will be updated in time, according to Dave Lancashire, the developer. When asked if it will stay free, his reply was, “I can’t see changing the price, although you should tell people it will be $99.99 next week so GET IT NOW!”

Chinesegram

Price: $4.99

| Feature | Description |

| Tracing | Yes (optional) |

| Feedback | No automated feedback, just a layer of numbers to indicate where strokes should start |

| Free-form writing | Yes |

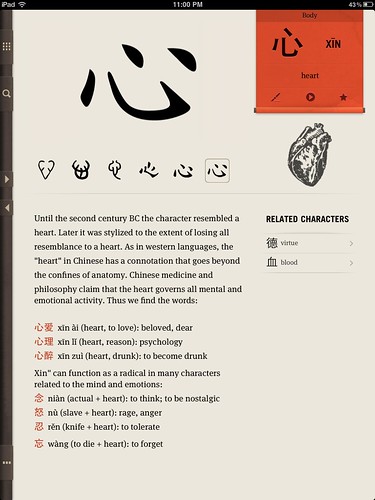

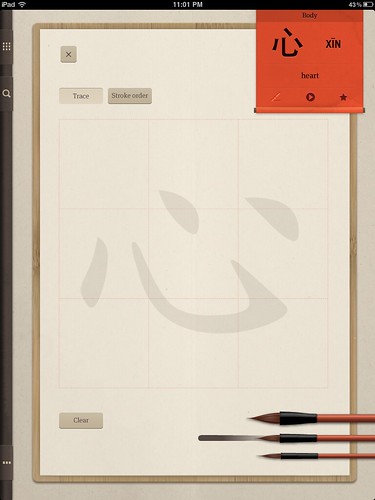

Chinagram is not free and contains a very limited number of characters, but in many ways, it’s my favorite of these apps. While it doesn’t teach strokes or radicals, it does show the evolution of the characters through various scripts over time, and offers graphics to help clarify the pictographic characters.

I also like how the app offers very free-form writing practice. There’s no computer program to tell you you’re right or wrong. There’s simply a faint guide which can be switched on or off, and some little guide numbers to help with stroke order, which are not tied to the tracing guide, and can also be independently turned on or off. This simple combination of options makes for a quite satisfying range of writing practice possibilities.

With Chinagram, it does kind of feel like you’re paying for design and pretty graphics, but let’s face it: characters are graphic. Chinagram offers an attractive and appealing, although somewhat limited, introduction to the writing of Chinese characters. I’d still want more instruction on how to write characters than this app offers, but it definitely goes farther than the three above.

(See also my original review of Chinagram.)

Chinese Handwriting Input + Notes

Price: Free (comes with the iPad)

| Feature | Description |

| Tracing | No |

| Feedback | Indirectly, because if you’re too far off in your stroke order, the character you’re trying to write won’t appear |

| Free-form writing | Yes |

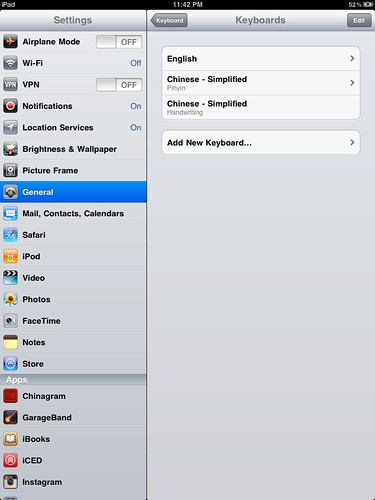

One of the things that struck me while reviewing these iPad apps is that (1) many of them assume some previous study of characters, and (2) if you’ve previously studied characters, there’s probably nothing better than just writing. And the iPad let’s you do that out of the box. All you need to do is enable Chinese handwriting input:

Once you’ve got that working, go into the “Notes” app (or anything that lets you write text, really), and just try to write something. You’ll learn a lot just by the act of writing the characters stroke by stroke, and identifying the one you want from the resulting list of characters. If you get a character totally wrong, chances are, it won’t be in the list. Try again.

(In the example above on the right, the correct character “写” meaning “to write” is written in a way that is clearly recognizable, but does not appear in the list of resulting characters because the stroke order/direction used was totally wrong.)

This really is not a bad option for practicing writing, especially if you have someone you can write to.

My conclusion: these apps are worth checking out, but better writing apps for Chinese are still needed!

I have a student intern at AllSet named Lucas, who kindly gave me his own feedback on the four apps above. Lucas has studied Chinese for three years in college, and is currently studying Chinese in Shanghai for the summer. I asked him to rank the four apps, and make some comments about each. Here are his independent picks, #1 being his favorite:

1. Chinesegram: “Seeing the picture and comparing the scripts and evolution helps me remember them better.”

2. Word Tracer: “Helpful for learning stroke order, but a bit over-sensitive, which can be frustrating.”

3. trainchinese Chinese Writer: “Kinda funny, I guess, but I don’t like the time pressure.”

4. Chinese Writer for iPad: “It’s too sensitive; it kept making me redraw the strokes.”

Related: iPad Apps for Chinese Study (2011)

27

Jun 2011The Naked Wedding

The Chinese neologism 裸婚 (literally, “naked wedding”) came up in an AllSet Learning client’s lesson, and I think it’s an interesting word with social implications, worth taking a look at.

The word has its own page on the Chinese wiki Hudong: 裸婚. The brief explanation is:

> “裸婚”指的是不买房、不买车、不办婚礼、不买婚戒,直接登记结婚的一种节俭的结婚方式。自古以来,婚姻一直都被人们看做是人生的头等大事,而婚礼的隆重与否直接体现了整个家族的地位。然而,近年来“裸婚”风渐渐盛行,成为“80后”最新潮的结婚方式。

And the English translation:

> “Naked wedding” refers to not buying a house, not buying a car, not having a wedding ceremony, not buying wedding rings, and just directly registering legally for marriage as a way to save money. Since ancient times, marriage has always been seen as a major event in a person’s life, the pomp of the ceremony directly reflecting a family’s social status. The gradual popularization of the “naked wedding,” however, has emerged as a new wedding trend for the post-80’s generation.

Industrialization and commercialization in a society are inevitably followed by a generation that rejects the new materialistic forms of social status, right? Here’s another sign that the forces for such a social change are building in China…