29

Dec 2011Shanghai’s Christmas Tourists

This year I attended the 8pm Christmas Eve mass at the St. Ignatius cathedral in Xujiahui, Shanghai. It reminded me why I normally don’t go to Christmas Eve masses in China. In short, it’s a zoo.

The reason is that Christmas Eve has become a popular holiday in Shanghai, although it’s mainly a date holiday. Traffic was horrible that evening, as couples all went out in search of a romantic winter evening. Many of them went to churches out of curiosity, to see how Christmas is celebrated there.

I imagine the “Christmas tourists” that wound up at Catholic churches were a little bored. Yes, there’s a choir singing Christmas music, but it’s still a Catholic mass, and not a Christmas program. (As I understand it, some other denominations do special Christmas programs to cater to the seasonal tourists.)

For the Catholic Church, it’s certainly a mixed blessing. On the one hand, the church has a rare opportunity to proselytize to a captive audience actively seeking out what it has to offer. (Christian churches are not allowed to actively evangelize in China, so if it’s done at all, it’s normally done quite subtly.) On the other hand, the Catholic Church is there for the faithful, and the Christmas tourists really are a bit of an obstacle to normal worship.

Some examples of how the Christmas tourist disrupt the mass:

– The tourists wander all throughout the church throughout the mass, often talking in loud voices

– The tourists take photos (with flash) and video all throughout the mass, often holding the device up high, distracting everyone

– The tourists take up good seats in a standing-room-only situation, but then try to leave the packed church after 20 minutes when they get bored

– The tourists outnumber the believers, so the priest tends to direct the sermon at them, capitalizing on the opportunity

– The tourists try to receive Holy Communion, even though the priest patiently and politely explains that it’s not for visitors, requiring the priest and eucharistic ministers to do a sort of mini-interrogation to anyone in the communion line that looks suspicious (and they’re surprisingly good at spotting the faking faithful!)

It’s the last one that bothers me the most. In China there’s a serious lack of respect for religion. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, given China’s history, but it’s quite startling to be presented with the fact in this way. It also makes me reflect on modern foreigners’ behavior in Buddhist temples (how bad are we?), but I honestly can’t think of anything I’ve ever seen that feels as bad as trying to receive Holy Communion after being specifically asked not to (in one’s native tongue).

Here’s one tourist’s account (from Weibo), which offers a nice (more respectful) perspective:

> 奔波的一天最终归于平静~第二个教堂平安夜,徐家汇天主教堂真的很美,典型的哥特建筑,宏伟壮观,空灵的圣歌,神圣的仪式…就是人太多,挤死了~信仰果真是一种强大的力量。跟着做弥撒时神父在我头上点了几下,没有给我圣体吃,而那些基督徒们在咀嚼圣体时怀着怎样一颗敬畏感动的心~安~

Here’s a rough translation:

> A busy day eventually ended peacefully… My second Christmas Eve at a church. The Xujiahui Catholic Church is really beautiful, with classic gothic architecture, really magnificent, lovely hymns, and a holy ceremony… But there were just too many people; it was super crowded. Faith is indeed a powerful force. Following along in the mass, the priest nodded at me several times, but didn’t give me the Eucharist to eat. But those Christians chewing on the Eucharist were filled with some kind of reverent emotion. Peace.

I assume the priest “nodding” at her was him giving her a blessing. Any non-Catholic can go up in the Communion line and get a blessing, but they’re supposed to cross their arms to signal that they’re not there to receive the Eucharist.

Anyway, lesson learned… next year I won’t be going on Christmas Eve again!

23

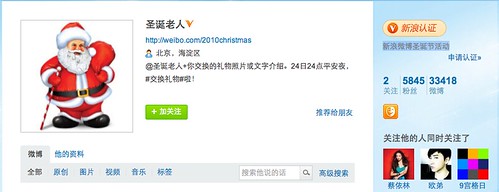

Dec 2011Even Santa Claus is on Sina Weibo

A quick search on Sina’s Weibo today revealed that Santa Claus (圣诞老人) uses the service, and his identity has even been verified (that’s what the “V” stands for: 新浪认证, or “Sina Verified”).

But actually, a little bit more reading reveals that the account is used for Christmas promotions by Sina itself:

> 新浪微博圣诞节活动

That account is actually a year old, though. There’s another one for 2011, based in Guangzhou rather than Beijing (??).

Hmmm, does this qualify as abuse of an identity verification system, at a time when Beijing is supposedly cracking down on accounts that aren’t clearly linked to real people? I’m sure Santa Claus is outraged.

Anyway, merry Christmas! 圣诞快乐!

20

Dec 2011Xiami’s Unofficial iPhone App

Recently a Chinese friend got me into Xiami. In case you’ve never heard of it, TechRice describes it like this:

> Xiami is perhaps the closest China has to a Last.fm, though in Last.fm users have to pay monthly subscriptions to listen to songs and Xiami is still completely free up until the point of download.

So think “social music site,” with both free and paid offerings.

I was interested to see how the site offers its iPhone app for download:

So what that little popover message is telling you is that you have to download the iOS install file (.IPA file), and it only works on (illegally) jailbroken iPhones.

I’ll admit I don’t have a lot of experience with Chinese iPhone apps; I mainly just use a handful of them. I’m curious how many other relatively large and popular services are doing it this way now. Xiami as a service seems much “more legal” from a western perspective than services like Baidu’s MP3 downloads, but then they go and do this with their app (presumably because Apple won’t approve the app).

Anyone?

More about Xiami:

– China’s Internet Music Industry, You Pay For Music Now (TechRice)

– Xiami versus Grooveshark (TimeOut Beijing)

16

Dec 2011The Upcoming Skritter iOS App Looks Awesome

And by “awesome,” I mean flashy (or sparky?), fluid, and fun! Check out this video:

More info on the Skritter iOS page. This is definitely an app I’ll be getting as soon as it comes out, and I’ll be reviewing it in the future.

13

Dec 2011yex, AKA HX

For the longest time, I wondered why 恒鑫茶饮 used the English name “yex.” Here’s the logo:

Doesn’t it seem like “Heng Xin” or something related would make more sense for a company called 恒鑫茶饮? Eventually it dawned on me that “yex” is actually “HX” in “fancy lettering.”

Which one do you see?

08

Dec 2011Chinese Lyrics (with Pinyin) for Christmas Songs

Sinosplice’s Christmas Songs in Chinese have been popular every year around this time for a while now, and one of the most common comments let has been, “can you provide the lyrics in pinyin?” Well, it’s actually quite a lot of work to assemble all the (correct) lyrics, which is why I hadn’t done it before. This year, however, I decided to leverage some of AllSet Learning‘s resources and finally make it happen. (They may not be perfect though, as some songs were manually transcribed, and the audio was a little unclear. So if you catch any errors, please leave a comment, and we’ll update ASAP.)

So for the MP3 audio, go to the original Christmas Songs in Chinese post. For the lyrics (simplified characters and pinyin), download here:

Christmas Songs in Chinese lyrics (1.2 MB ZIP file containing PDFs)

Note: Some of these songs (especially the religious ones) do not have easy lyrics! Think twice before you try to use some of these songs as study material.

Merry Christmas!

01

Dec 2011Nicki Minaj’s Chinese Tattoo

Nicki Minaj has one of the more interesting Chinese tattoos out there. It’s not particularly pretty (it was clearly not the ink work of a Chinese calligrapher!), but the traditional characters are correct mostly correct and legible. The tattoo:

It means “God is with you.”

The tattoo uses traditional Chinese characters:

> 上帝與你常在

Here’s the simplified character version (it only differs by one character):

> 上帝与你常在

And pinyin:

> Shàngdì yǔ nǐ cháng zài

The grammar, though, seems a little strange to me. The sentence I’m used to hearing (at Catholic churches in China) is:

> 上帝与你同在

同在 is just a fancy way to say “to be with.” So what’s up with 常在? You’re probably used to 常 taking on the meaning of “often,” “frequent,” or “usually,” as in 常常, 经常, 通常, 平常, etc. “God is usually with you” certainly doesn’t seem like the most confidence-insiring blessing.

Here, though, 常 is used more to refer to a “normal,” unchanging, continuous state. So although neither this sentence nor the Catholic version is everyday Chinese, they both make sense.

When I asked my wife for her impressions on Nicki Minaj’s tattoo, she made the following comments:

– Those characters look like they were written by a poorly-educated elementary school student.

– She should have chosen simplified characters; less ink is less pain.

– Foreigners’ Chinese character tattoos are like our stupid English t-shirts. But at least we can take off the t-shirts whenever we want.

28

Nov 2011Black Hole for Smart Slackers

Kaiser Kuo posted an article about Beijing last month, entitled Peking Purgatory, Is Beijing a Black Hole For Smart Slackers?

While the article is about Beijing, this paragraph definitely reminded me of some of the things I’ve also felt about Shanghai:

> Beijing, after all, has much going for it in these heady days. Possibilities abound. Opportunity knocks. There’s a buzz here, a palpable energy. It’s a city with edge, full of quirky characters doing interesting things. Change is the one all-pervasive constant. The Beijing zeitgeist is a shape-shifting polymorph, the city a suitable setting for self-reinvention. It’s impossibly big and yet it offers the intimate charms of a small town – that sense of community that many of us found missing back home.

Those that have taken root in Beijing probably might be forgiven for assuming that this feeling is not to be had in Shanghai. I’d say the main difference is that Shanghai is not “impossibly big.” Part of its charm is that the “downtown” city area (obviously, Pudong is not included) is actually relatively small.

But “black hole for smart slackers…” aptly put.

22

Nov 2011Shanghai Thanksgiving Dilemma

Shanghai has changed quite a bit since I last blogged about Thanksgiving dinner in Shanghai in 2005. And the Thanksgiving dinner buffet business is booming. Even the Mexican restaurants are doing Thanksgiving dinner spreads. Here are some of the listings:

– The Big List: Thanksgiving Dinners (SmartShanghai)

– 2011 Thanksgiving Dinners – Shanghai (Shanghai TALK)

– Thanksgiving 2011 (Fields)

In 2005 I called “reasonable prices” around 150 RMB per person. Now it’s difficult to find T-Day dinner deals for less than 300 RMB per person, and many are around 5-600 RMB. Kinda makes you want to stay home and be thankful you don’t have to participate in the consumption orgy.

But what if you want to have an American-style Thanksgiving at home in Shanghai? It’s possible, but also not cheap. The biggest problem is that if you want to buy turkey, you have to buy a whole bird. I don’t quite understand this. Why can’t the birds be carved up and sold in pieces? Most Chinese people aren’t crazy about turkey, but would probably buy some to try out if it could be purchased in moderation. As for me, I’d like some turkey on Thanksgiving Day, but I’ll be staying in this year, and I’m certainly not capable of taking down a whole turkey.

Suggestions welcome!

11

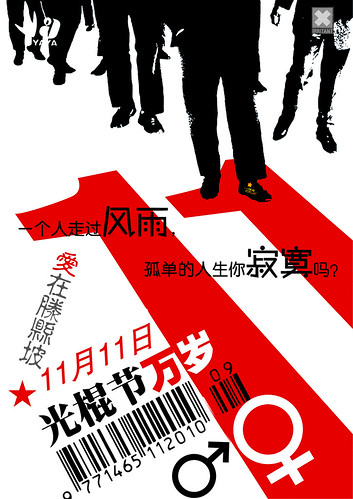

Nov 2011China’s Bachelor’s Day

China’s “Bachelor’s Day” (光棍节) is becoming more and more internationally known. It is still, however, not what you might call “well-known” (that Wikipedia article, for example, is the shortest Wikipedia article I’ve seen in years!). Urban Dictionary offers this definition for “bachelor day“:

November 11, a day represented by four digits of 1, dubbed by young single Chinese. The “Bachelor Day” has been initiated by single college students and, although enjoys no holiday leave, has become a vogue of the day among single white collars.

I wish I could get lucky on the Bachelor Day this year.

It seems that this holiday has yet to catch on outside of China, but one is the loneliest number in any culture, so it may just be a matter of time. Sadly enough, this particular holiday is going to be more and more relevant to China, as the sex ratio imbalance here worsens. Already, I get the sense that the holiday is more relevant to single men than to single women here.

Anyway, the date for Bachelor’s Day this year is 2011-11-11, which is not only a rare concurrence of lots of 1’s in a date, but also extra bachelor-y.

Here are some images I collected from the web which show how this modern holiday is seen in China (and how it seems to focus on single men more):

There seem to be a lot of stick-like foods in the imagery, such as 油条 (fried dough sticks) and Pocky, and also a lot of cigarrettes:

And, of course, the holiday is also being used for marketing promotions. Taobao even set up a special page just for its Bachelor’s Day (AKA “Singles Day”) promotions: 1111.tmall.com:

I have a feeling we’ll be hearing more and more about this holiday in years to come.

Finally, on a personal note, today is the day that my own daughter (our first child) was born! Hopefully we’re not condemning her to a life of loneliness.

I’m not planning to do any baby posts here (at least, not until the language acquisition begins), but I might be posting a bit less in the (sleep-deprived) days to come.

08

Nov 2011Units of Beer

This topic came up in an AllSet Learning client’s lessons recently, and I’m certainly a proponent of 啤酒 education, so I thought I’d share this useful info on Sinosplice:

Units of Beer

– 1 drop = 一滴

– 1 glass/cup = 一杯

– 1 can = 一听

– 1 bottle = 一瓶

– 1 6-pack = 半打

– 1 12-pack = 一打 (same as “a dozen”)

– 1 case = 一箱 (quantity may vary)

– 1 keg = 一桶

Tone Notes:

1. Remember that for all uses of 一 above, the tone change rule changes “yī” (1st tone) to “yì” (4th tone).

2. 打 is normally read “dǎ,” but when it means “dozen,” it’s read “dá.”

03

Nov 2011How SRS Works (video)

Just saw this great video on SRS (spaced repetition system/software), which provides an illuminating visual explanation:

> The video shows a grid of factoids, where new factoids are being presented at a constant rate. Over time, the factoids begin to fade to black… the closer they get to black, the closer they are to being forgotten. However, if they’re “recharged” by being relearned, they advance up a tier (represented by the color and number of the cell). The higher the tier, the longer it takes for the factoid to be forgotten. If at any point, a factoid gets completely forgotten, it is sent back down to the lowest level.

Be sure to click on “Show more” under the video to see the full explanation.

Via @ajatt.

01

Nov 2011Momochitl

Over the weekend I met up with Patrick Lin, a former student of mine from ZUCC in Hangzhou. It’s hard to believe that it’s been over 10 years since I first taught him English all those years ago. At the time, I was a 22-year-old kid fresh out of college, and the students in that class were 21. Now he’s married and has a kid already.

After college, Patrick went to Scotland and studied golf course design. He later moved to Beijing, where he applied what he had learned for a while, but apparently got the entrepreneur’s itch and opened a coffee shop in Beijing. (Lesson learned: don’t start with a big coffee shop.) Later he decided to open a business in Shanghai selling gourmet popcorn under his own brand called Momochitl.

Anyway, this past weekend I finally made it out to Patrick’s shop and got to try some of his popcorn for myself. It’s imported American corn and ingredients, and it’s good stuff! You can even order it on Taobao if you’d like to try it.

I’m proud of a former student for starting his own business in largely uncharted territory. He’s got all kinds of ideas for his business, and I’m interested to see how it grows.

One of the most interesting details for me, though, was the name: Momochitl. It starts out sounding Japanese (“momo” means “peach” in Japanese), but then “chitl” is decidedly un-Japanese and just un-Asian altogether. It sounded Aztec to me. Sure enough, Patrick’s explanation is:

> “In the 16th century, Aztec Indians would use local popcorn as decoration in worshiping their gods,” explains Momochitl owner Patrick Lin. “Momochitl is the earliest word for popcorn.”

“The earliest word for popcorn!” Nice. If you Google “momochitl,” you’ll find that Patrick’s business is already overtaking the search results, but one interesting page is simply the Wikipedia page for popcorn, in the Nahuatl language. Nahuatl is the modern term for the family of languages descended from the Aztecs.

Interestingly, Patrick is marketing his popcorn mostly under the name Momochitl, but if you insist on Chinese, it’s 蘑球 (“mushroom balls”??). If you like popcorn, give it a try!

28

Oct 2011Happy with a Dog

These days I rarely post photos, but this one was too cute. I passed this elderly lady with her dog on my way to work the other day. I asked if I could take her photo, and she cheerfully agreed.

(The dog wasn’t quite as cheerful as the old lady. After taking the picture, I tried to pet him, and he suddenly turned into a snarling, snapping fury.)

25

Oct 2011Living with Dead Hearts: Language

By now I hope you’ve heard of Living with Dead Hearts, a documentary project spearheaded by Charlie Custer of ChinaGeeks which aims to spread awareness of a very serious social problem in China:

> Each year, as many as 70,000 children are kidnapped in China. They are not held for ransom; rather, they are sold. The lucky ones are sold into new families who raise them like adopted children; others are sold into slave labor, marriage, prostitution, and lives on the street. Most children who are kidnapped will never see their parents again.

> Living with Dead Hearts follows several parents whose children have been kidnapped as they struggle to track down their kids and to make sense of what has happened to them. Along the way, the film also looks at the experience of kidnapping and growing up in a strange family from the child’s perspective and examines the lives of street children.

Aside from helping get the word out about this project, I’d like to offer a few comments for students of Chinese, since many readers of this blog fall into that category. From a language learning perspective, there are some things you want to be aware of before watching even the trailer for this documentary:

-

Many of the people in the documentary speak in heavily accented Mandarin, if not full-on “dialect” (read “topolect,” which might as well be a separate language, in many cases). If you’re a learner trying to use Chinese movies as study material, this is not a film to beat yourself up about for not understanding; most Chinese native speakers will be unable to understand some of the people in this movie without the aid of subtitles.

Dialect is sometimes used as a literary device; unfortunately, in this film it’s simply a cruel reality: the victims interviewed are often from the countryside and can do little to fight back or get help.

- The word 拐卖 means “to abduct and sell,” the verb for what we commonly refer to as “human trafficking.” It’s not a verb you normally hear much. In the trailer below, you hear the grown-up 拐卖 victim use the term.

-

The Chinese word in the background behind the title “Living with Dead Hearts” is 躯壳. Although not an everyday term, this is one of those words that has a definite “correct” reading in the dictionary (“qūqiào”), but don’t be surprised if some of your Chinese friends read it as “qūké.”

The meaning of the word is “body; outer form” (not including the soul). My New Age Chinese-English Dictionary provides an appropriate sample sentence:

失去精神,就成了没有灵魂的~。 Once the spirit is lost, what is left is only the body without the soul.

The trailer is below. If you haven’t watched it yet, please do.

Related Links:

– Living with Dead Hearts (official site)

– Living with Dead Hearts (on ChinaGeeks)

– China’s Missing Children (on Foreign Policy)

– Child Trafficking and Sina Weibo (on ChinaHush)

– Child kidnapping in China: A case study (on Danwei.org)

– Child Kidnappings in Anhui, Chinese Netizen Reactions (on chinaSMACK)

– Interview with Charles Custer, director of ‘Living With Dead Hearts’ (on Lost Laowai)

– Missing children and how parenthood killed my chances of being a manly-man (on Imagethief)

14

Oct 2011Camus on China

Albert Camus was my favorite of the authors we read in high school; The Stranger (《局外人》 in Chinese) was my favorite book. Recently I was reading some of Camus’s famous quotes, and I was struck by how applicable many of them are now to modern China:

“At any street corner the feeling of absurdity can strike any man in the face.”

“Culture: the cry of men in face of their destiny.”

“The society based on production is only productive, not creative.”

“The myth of unlimited production brings war in its train as inevitably as clouds announce a storm.” [Uh oh…]

“Without freedom, no art; art lives only on the restraints it imposes on itself, and dies of all others.”

“A free press can, of course, be good or bad, but, most certainly without freedom, the press will never be anything but bad.”

“By definition, a government has no conscience. Sometimes it has a policy, but nothing more.”

“The welfare of the people in particular has always been the alibi of tyrants.”

“All modern revolutions have ended in a reinforcement of the power of the State.”

“Every act of rebellion expresses a nostalgia for innocence and an appeal to the essence of being.”

“Every man needs slaves like he needs clean air. To rule is to breathe, is it not? And even the most disenfranchised get to breathe. The lowest on the social scale have their spouses or their children.”

“As a remedy to life in society I would suggest the big city. Nowadays, it is the only desert within our means.”

“It is a kind of spiritual snobbery that makes people think they can be happy without money.” [Many, many Chinese people I know would whole-heartedly agree with this statement.]

“He who despairs of the human condition is a coward, but he who has hope for it is a fool.”

“Blessed are the hearts that can bend; they shall never be broken.”

In my experience, Albert Camus (阿尔贝·加缪) is not very well-known in China.

Sources: BrainyQuote, Wikiquote

11

Oct 2011On the Limits of Ni Hao

After my last post on 你好吗, which I consider “a greeting on training wheels,” I received an email from a reader about the non-interrogative, even more widely used greeting 你好. Brad’s email (slightly edited):

> I drove to a friend’s house [in Qingdao] to pick him up for supper. My friend doesn’t speak English and I’ve only known him for a few weeks. When he got into the car I greeted him with “你好!” (paying careful attention to not say “你好吗?” ha ha). To my complete surprise, he turned to me and said “You know Brad, I don’t want you to take this the wrong way, and I’m not saying this to be critical of your Chinese, but I think we’ve now moved beyond having to say 你好.”

> I think I had a dumb look on my face and didn’t know what to say… nor did I know exactly what he meant. I asked him “What should I say? I don’t think I understand.”

> He said that 你好 is hardly ever used by people who know each other well, and it’s fine and dandy to use it between people who know there’s a formal barrier between them (age, acquaintance, colleague, stranger, superior, etc.), but that he considered me a close enough friend to no longer be at the 你好 stage.

> To me, this sounded exactly like the French “vous” vs. “tu” or Spanish Ud. vs. Uds. Again, I asked him what I should then say in such a context. His answer — say nothing! I said that’s impossible… I must have to say something like 最近很忙吗? or even 吃饭了没有? He said I could if I wanted, but it should sound sincere instead of just an insincere verbal gap-filler (I’ve actually heard that line a few times from colleagues who have stopped me dead in my tracks for saying something perceived to be an unnecessary “insincerity” like “you’re wearing a nice sweater today.” I now longer give compliments unless it’s pertinent to the situation, and you know what? Neither does anyone else!).

> I asked him then what he would say, and he just gave me that “E”* grunt noise that might be the closest thing to a brief, low toned and quick “hey” in English, the same kind used to acknowledge someone you know while on the fly when passing them in the hall at work. He then said I could get right to the point after the grunt.

> Shocked! That was my reaction. But even more shocked by the fact that I now can’t recall any “friends” ever addressing themselves with 你好 when we meet as a group. It’s always that E!*, followed by “name”, and then something straight to the point. Even my colleagues (who are friendly with each other, but not friends) don’t say 你好 to each other.

> I know there might be a North-South divide on some of these issues (my southwestern friends all said for them 味儿大一点 meant more 辣的,the Northern friends thought it meant 加香, and the deep Southerners didn’t know what it meant), but I’m wondering if you ran into this simplest of linguistic mysteries in Shanghai?

06

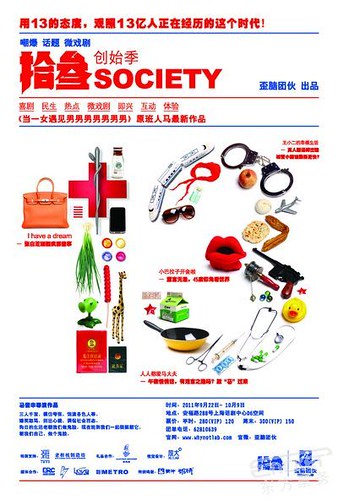

Oct 201113: a micro-play about this crazy society

Not long ago, my wife and I went to see a Chinese version of the classic play 12 Angry Men. Over the October holiday we decided to go see another play (comedy this time), and what better play to follow 12 Angry Men than a new independent “micro-play” (微话剧) called “Thirteen” (拾叁, which is 大写 for “十三“)?

We ended up really enjoying the 90-odd minute performance. It was created by a group which calls itself “Why Not” in English, and 歪脑 (a transliteration into Chinese which means something like “skewed brain”). The whole play was performed by only three talented young actors:

The promotional poster for the play we saw:

Here’s my partial translation of the micro-play’s description, taken from the introduction on the Why Not website:

> Micro-play “Thirteen” (Society)

> Keywords for “Thirteen”

> comedy, lives of the people, current events, micro-play, improv, interactive, experiential

> History of “Thirteen”

> Shísān: shortened form of the classic Shanghainese slang “shísān diǎn” (thirteen o’clock). “Shísān diǎn” was originally a transliteration of the English word “society,” a pejorative term used in the last century for those who closely followed the trends of the times and obsessed over socializing. Later it was extended to refer to people or things which are “not normal, fun, funny,” and can often have a positive connotation.

> English “society” could refer to the whole of society, a club, or social life.

> The micro-play “Thirteen,” makes use of the “funny, spoof” meanings, but puts more emphasis on the “society, lives of the people” aspects.

> Tagline for “Thirteen”

> Use the “thirteen” attitude to view this era, which 1.3 billion (13亿) people are experiencing together!

> Content Outline of “Thirteen”

> This is the funniest era. It is also the evilest era.

> Here, total luxury and homelessness coexist, Lamborghinis and tractors coexist; here, food prices and rocket ships soar, as do oil and Maotai. Here, there are both Li Gang and Li Chengpeng; there are both Guo Guangchang, and also Guo Meimei. There are the Olympics and the World Expo, as well as the Red Cross. Here, both “China’s Got Talent” and “China’s Sick People” are on every day, while both the country’s GDP and the water levels in its flooded cities are rapidly rising…. Here, what follows hope is disappointment, but following disappointment, a new hope may spring up yet again….

> As it happens, we’re living in just this confluence of events. But without all these events we witness; this play could not exist.

> Whether you’re worried about the stock prices (as disappointing as the Chinese soccer team), or our food quality (as unreliable as the new bullet trains), or, like the Forbidden City, you just can’t hold onto what you treasure most, to tell you the truth, we can’t solve a single one of these issues. But there is one thing we can do: as these dog days make faces at us, we can at least find an opportunity to make some faces back. This opportunity is in “Thirteen.”

> So come on, take 90 minutes of time, 1000 square meters of space, audience and actors, stage and backstage, laughs and curses, pretenders and morons, and let’s all make faces back, and at each other.

> Content and Segments (these may change at any time; this is a Chinese characteristic, if you know what we mean):

[I left these “segments” out, because they didn’t seem to reflect what I saw, as the site warns. Here are the segments we saw, in my own words:]– Teacher and student skit

– A crackdown on street vendors skit

– A “I won’t stay with you if you can’t provide for all my material needs” modern woman skit

– A series of interview skits

– A kung fu monk skit

– A doctor seeing patients skit (including a very racy but cleverly acted scene where a prostitute brought in a customer who had OD’d on Viagra and collapsed)

– A visit from Cecilia Cheung (张柏芝) skit

This play was quite challenging to follow, because not only was it performed with rapid-fire delivery, but it also referenced a lot of current events, with internet culture thrown in too. There were references to both the Wenzhou bullet train wreck as well as Shanghai’s recent subway accident, for example. Plenty of social commentary.

I enjoyed all three actors, but 苏永豪‘s was especially memorable (pictured above; the guy in glasses). He played so many roles, including several hilarious cross-dressing ones and a number of accents, and he was very funny in all of them. He was also really good in the impromptu audience interaction parts. A real pro performer.

Anyway, if you’re up for the challenge of trying to follow a modern Chinese play, this one probably isn’t an easy one to start with, but it’s definitely an interesting one. It had a fair amount of slapstick and action, too, which would keep you engaged even if you don’t follow a lot of what’s said. At 120 RMB per ticket (here), it’s not cheap, but it’s a much better entertainment investment than Transformers 3!

29

Sep 2011A Greeting with Training Wheels

How do you ask “how are you?” in Chinese? Most textbooks or other study materials include the classic greeting 你好吗? (“how are you?”) right in the first lesson. From a course creation perspective, this greeting is great. It builds on the universal greeting 你好 (“hello”) by just adding one word, plus it allows an opportunity to teach the very basic grammar pattern of using the question particle 吗 to create yes/no questions. It’s also very easy to answer, and the classic response 我很好 (“I’m fine”) reinforces (1) the basic “N + Adj” sentence pattern in Chinese, as well as (2) using only super basic, core vocabulary.

So what’s the problem?

Well, Chinese educators’ dirty little secret is that Chinese people themselves rarely use the greeting 你好吗? with each other. Some people will tell you this expression actually evolved out of a perceived need for Chinese greetings to more closely resemble western ones, which might be easier for westerners to learn. I’m not sure how much truth there is to this theory, but based on years of observation, I can confirm what many others have also observed: that native speakers very rarely use 你好吗? with each other.

When I first learned this “dirty little secret,” I was quite indignant. Why would you teach learners something that no one ever says? It’s irresponsible and lazy. It certainly wouldn’t be the first time that educators underestimated the intellect of the learners. And it does seem that many Chinese educators continue to feel that it’s a good idea to teach 你好吗? to beginners (perhaps for the reasons listed above). So in my work at ChinesePod over the years, I’ve tended to avoid 你好吗? as much as possible.

But over time, I’ve noticed another thing. Chinese people do say 你好吗? to foreigners. They’re especially likely to use it with foreigners when they know the foreigner knows very little Chinese, or if they suspect as much and are just testing the waters. (It can also be used as a barb in a language power struggle, as in, “OK, if you insist, I’ll speak Chinese with you… 你好吗?“)

So what’s going on? Are these Chinese speakers being racist jerks? Are they thinking, “this learner can’t possibly handle more than this”?

For those embittered by too many language power struggles, it might be tempting to think this way. But for most cases, I don’t think this is the case. When I reflect on my own English interactions in China, I can find similar situations in English. Take this fabricated dialog for example, which I’m almost sure I have acted out in real life several times in the past:

Me: Hi, how’s it going?

Student: [confused] Going?

Me: Hello, how are you?

Student: [visibly brightening] Fine, thank you. And you?

Me: I’m great.

Now, if this were my own student, I’d quickly teach him the way Americans actually greet each other nowadays, covering all the basic “how” and “what” informal greetings. But if it were just a very short conversation with someone who doesn’t really want to learn real English anyway, then “Hello, how are you” served its purpose.

This is why I now view the 你好吗? phenomenon as a sort of linguistic training wheels. It’s something you learn early on, and then try to move away from as quickly as possible. Key to the equation (and the reason why I no longer consider the prevalence of 你好吗? in Chinese textbooks to be a total blight on the entire industry) is the fact that Chinese native speakers will sometimes use it with learners. This is a fact that can’t be denied. But any serious learner won’t be using the training wheels for long (if he ever did at all), and will soon leave 你好吗? far behind.

23

Sep 2011China Daily Show is great

Maybe I don’t read the right blogs, but it seems like China Daily Show isn’t getting nearly as much attention as it deserves. This China-centric Onion-style “news” site is hilarious. It describes itself like this:

> China Daily Show is not affiliated with China Daily or The Daily Show and is intended for humorous purposes only. All events, characters, names and places featured are products of the authors’ imaginations, or are used fictitiously.

Here are some recent headlines to get you started:

– 80% of Chinese cuisine ‘shanzhai’: expert

– WHO downgrades Chinese culture to “cult,” urges strong caution

– Thousands of men now straight after gay website blocked in China

– Biden completes “Man of the People” tour by becoming Beijing cabbie

– Tibet, Xinjiang vital to keep China chicken-shaped: WikiLeaks

– Chinese skipper snares, eats mermaid

– Beggar not actually an erhu player: Erhu player