04

Feb 2013The Chinese Grammar Wiki Is Kicking Ass

Yes, not often are such bold words warranted when discussing online resources for grammar, but in this particular case, it’s pretty much required.

The AllSet Learning News blog has the full story, but here’s the key takeaway on all the progress the Chinese Grammar Wiki has made over the past year:

- Increased total article count from 500 to over 1200.

- Added English translations for all A1 (beginner) and A2 (elementary) level grammar points.

- Added pinyin to the introductions of many articles.

- Overhauled search engine for greater accuracy and depth.

- Added a “grammar box” to the top right of all grammar point pages, featuring level, similar grammar points, and keywords.

- Added keyword pages (example: 不) and keyword index.

- Set up disambiguation pages for toneless pinyin (example: “hao“).

- Broke long grammar point lists down into themed sections.

- Began adding crucial comparison pages, in which two similar grammar points are compared (example: 不 and 没).

- Began collecting grammar points in earnest for the forthcoming C1 (advanced) list.

Also, there’s now a Twitter account specifically for Chinese grammar-related questions and requests: @ChineseGrammar.

If you haven’t looked recently, it’s definitely time to check out this resource again. It’s not going away, and it’s really gaining momentum.

01

Feb 2013China’s Iron Man

Recently the WeChat app was kind enough to alert me to this news story:

This, as you know, is an apolitical blog, and stories like this are among the least interesting to me personally. But this guy’s name demands to be noticed. His name is 刘铁男. That’s “Liu Iron Man.” His parents named him “Iron Man.” That’s kind of awesome. I haven’t been forced to take notice of a name like this since I discovered the lovely lass named 黄雪 (“Yellow Snow“).

At this point, I’d also like to give a shout out to a friend who goes by the name of 铁蛋 (“Iron Eggs,” i.e. “Iron Balls”).

Who says you can’t have fun with a Chinese name?

29

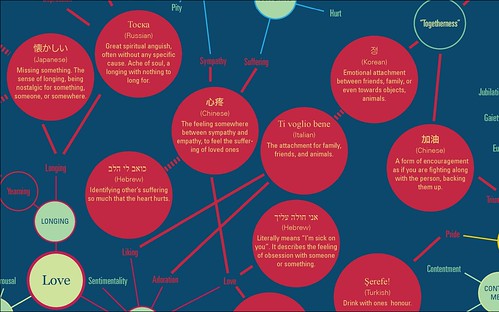

Jan 2013The Shrinking List of Things You Can’t Buy in China

I remember my list of things I needed to buy on my trips back to the States used to be something like this:

1. Shoes (I’m size 13)

2. Pants/jeans (I got some long legs)

3. Deodorant (I like Speed Stick)

4. Anti-diarrhea pills (there are some things you never totally get used to…)

Nowadays you can find almost everything on Taobao, though. I forgot to get deodorant on my last trip home, but thanks to Taobao, I think I can cross it off the list anyway:

Same goes for item #1:

I’m not going to buy my pants on Taobao (yet), and I haven’t seen the type of anti-diarrhea pills you can get in the States here (when you need ’em, you need ’em!), but I imagine it’s just a matter of time before “the list” is gone completely.

Food aside, what items are still on your list? (And run a search on Taobao before posting your reply!)

25

Jan 2013Quick Review of PinYin Pal

OK, so I feel a little dirty typing out “PinYin,” but that is the name of the app. (Words can be capitalized in pinyin, but syllables within words should not be capitalized or spaced out.) I guess that’s my main linguistic complaint about PinYin Pal for iPad; it seems to confuse syllables with words. Still, it’s a pretty decent “Words with Friends” clone (read: Scrabble clone), and the incorporation of characters is done in a smart way. The relative short length of pinyin syllables (as opposed to English words) is also cleverly skirted with a purple extension tile.

Some screenshots of me playing an AllSet Learning teacher:

Right from the get-go you can see that we had a little bit of trouble coming up with long pinyin syllables.

Then we started to successfully create longer syllables.

Finally, we were forced to figure out how to use the purple “spacer” block. (It turns into a blank orange square when you place it. You can see it near the top under “jun.” Blank tiles make you choose a letter, and then the letter appears on the tile, but with no points.)

It’s true that native Chinese speakers don’t have a huge advantage when playing this game, since you’re creating syllables rather than words. (In fact, you can’t string syllables together and create actual words, which is a little frustrating.) So in order to play, the learner just has to know what syllables are possible in Mandarin (and I hope you have the iPad Pinyin app for that), and be able to match the syllables you created to one correct character and definition. Tones are added when you choose your character, but you’re not tested on them.

Overall, the game felt less fun than Scrabble. I think it’s mainly because there are so few syllable finals in Mandarin (you can’t end a syllable in m, p, g, z, y, etc.), and this can slow the game down a bit. Still, it was fun playing this classic game in Mandarin, and the app is free! It was also fun playing such a well-known English-language game with a Chinese person who had had absolutely no exposure to Scrabble (or “Words with Friends”). So if you’re learning Chinese, check it out: PinYin Pal.

23

Jan 2013Unspeakable Travel Possibilities

ChinesePod Jenny was telling me that she read about a story told by the CEO of C-trip (携程). C-trip was trying to make a Weibo post about “independent travel” (i.e. not travel with a tour group). In China, this kind of travel is called 自由行. 自由 means “free” (as in freedom), and 行 is an abbreviation of 旅行, which means “travel.”

Well the word for “freedom” tripped the censorship filter, and the post was rejected.

So they figured that they could alter the word 自由 by using the character 游 instead of 由. 游 is a part of 旅游, another word for “travel.” That way you get 自游行 instead of 自由行. Identical pronunciation, and the meaning still comes across pretty clearly.

The post was rejected again, for having tripped the filter.

The reason is that they had unintentionally created the word 游行, which is the Chinese word for “demonstration” (as in the protest kind).

Whether or not the facts are 100% accurate, Chinese people find this kind of story quite amusing. There’s not much you can do about the current situation but grin and bear it. One does wonder how much longer this particular charade will carry on, though…

[I don’t have a link to the original article; please share it if you have it!]17

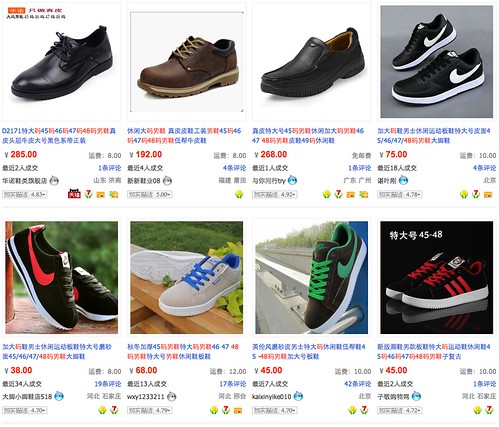

Jan 2013Chinese Emotions for which There Are No English Words

A friend pointed me to this article: Emotions For Which There Are No English Words. A nice intersection of some of my favorite topics: semantics, translation, psychology, and infographics. You’ll need to go to the site for the full infographic (it’s zoomable), but here are the Chinese words that make an appearance:

The Chinese words are:

> 心疼: The feeling somewhere between sympathy and empathy, to feel the suffering of loved ones.

Literally, “heart aches.” This one isn’t too hard to understand.

> 加油: A form of encouragement as if you are fighting along with the person, backing them up.

Literally, “add oil.” It does take a little bit of time to get used to how when you say “加油!” you’re actually putting yourself on the same team as the enouragee, somehow. (Similar deal with Japanese 頑張って.)

> 忐忑: A mixture of feeling uneasy and worried, as if you can feel your own heart beat.

(That one is also kind of famous for its characters… good ideogrammatic fun.)

> 纠结: Worried, feeling uneasy, don’t know what to do.

纠结 probably gets my vote for “newest super useful slang word that you won’t find in a textbook,” but it’s not just a word-fad that’s going away anytime soon.

I really like this next Japanese choice. It’s once of my favorite Japanese words:

> 懐かしい: Missing something. The sense of longing, being nostalgic for something, someone, or somewhere.

The weird thing about the word 懐かしい is how often it’s used as a complete sentence, usually as an exclamation. When you’re not used to the word, and you see someone confronted with something dear but forgotten from childhood, and then they bust out with “nostalgic!” it seems very odd at first. It’s like one word to say, “oh wow, that really takes me back.”

Just thinking about using 懐かしい is kind of 懐かしい for me. (I do miss Japanese!)

14

Jan 2013How Poisonous the Air

How poisonous would the very air you breathe need to be to drive you away from a city you otherwise love? The question seems kind of absurd, but I would think it has become very real to the residents of Beijing (especially the non-locals).

From TeaLeafNation:

> So a 500 reading of particulate pollution was considered “crazy bad” and “beyond index”?

> Try 993. That is a reading recorded at a monitoring station in central Beijing on the evening of January 12, according to the Beijing Municipal Environmental Monitoring Center.

Shanghai’s was something like 160 the other day, and we thought that was bad. 993 is kind of incomprehensible to me.

My family is currently planning to visit Beijing for Chinese New Year (and taking the baby), but this whole air pollution thing in Beijing is pretty scary…

08

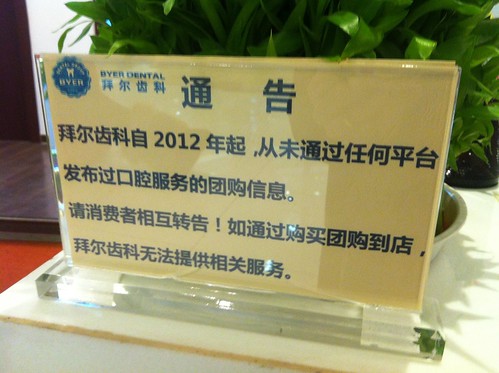

Jan 2013No group buying deals for you!

I went to the dentist last week and saw this sign:

It reads:

通知

拜尔齿科自2012年起,从未通过任何平台

发布过口腔服务的团购信息。

请消费者互相转告!如通过购买团购到店,

拜尔齿科无法提供相关服务。

Translation:

NOTICE

Since 2012, Byer Dental has not, on any platform,

published any group buying deals for dental work.

Please pass the word on! If you’re here through a group buying deal,

Byer Dental cannot provide those services.

Makes me wonder what happened. Fraudulent group buying (团购) deals online (created by the competition?), sending hordes of cheapskates in need of greater dental hygiene to Byer’s door? Or perhaps just a 2011 full of ill-advised group buying engagements in Byer’s past?

Is there no end to the evils brought on by all this wanton Groupon clonery?

05

Jan 2013MandarinTap Looks Interesting

Jut discovered MandarinTap. I haven’t bought it yet (it’s $2.99), but it’s available for iOS and Android. Anyone out there tried it?

Here’s the intro:

I’ll most likely get this later and follow up with a review.

31

Dec 2012Looking Back on 2012

Wow, this year December has turned out to be very low on posts. I’ve been trying to update twice a week, but I didn’t pull it off this month. I was in Florida visiting family for more than half the month, and blogging just didn’t happen.

While not blogging, I’ve been thinking a bit about how this 2012 went. I came up with two main conclusions.

It was a good year for AllSet Learning.

Again, I have to thank the exceptional bunch of people that have entrusted us to help them learn Chinese here in Shanghai. Our clients are our investors, and thanks to them, we’re going strong.

In 2012 AllSet Learning launched the Chinese Grammar Wiki, which has more than doubled in number of articles while quality of articles rises across the board (more on this later). We also released the AllSet Learning Pinyin iPad app in the first half of the year and the Chinese Picture Book Reader iPad app in the second half. Both are doing well, and I’m just so pleased to be making my designs a reality.

We’ve also had some more awesome interns, a trend which looks to be continuing into 2013. (Thanks, guys!)

It was a bad year for staying in China.

I’ve remained silent on the news buzz about Mark Kitto et al because I don’t really think it’s that much of a story. But the disturbing thing about it all is that this year a surprisingly large proportion of my close friends in Shanghai have either left or announced plans to leave.

It’s not that I expected everyone to stay in Shanghai forever. I always tell people that I’ll be in China as long as it makes sense, and due to the particular career path I’ve chosen, it makes sense for me to stay around longer than perhaps a lot of my friends that have taken up residency here. But it still seems a little strange that so many friends would decide to leave all around the time. I suspect that the “10 year mark” has something to do with it. We humans do tend to attach importance to that number.

The latest to leave Shanghai is Brad Ferguson, of the website BradF.com, which has long since ceased to be his domain, but it’s how I originally got in touch with Brad. He helped me move into my first apartment in Shanghai the first time we met, which I think was a pretty good sign that he was a decent guy.

Brad did one thing before leaving which I thought was quite interesting. He got a Chinese character tattoo. Seems like most of the time the ones getting Chinese character tattoos are white people that have never set foot in Asia, and oftentimes end up inking questionable symbols on their bodies. Brad, however, got a pretty cool Chinese poem tattooed on his arm:

Not sure exactly about the meaning of a white guy getting such a tattoo on his arm as he leaves China, but it makes me think.

11

Dec 2012Why Chinese Needs Post-Apocalyptic Steam Punk (with Dinosaurs)

At some point or another, many learners of Chinese here in China get the brilliant idea to buy Chinese children’s picture books and use them to learn Chinese. Genius, right? It’s got pictures, it’s for kids (so it’s gotta be simple), and it’s a story! What could go wrong, right?

You see, at the really low levels, China’s children’s books contain big, clear, colorful pictures, characters with pinyin, and sometimes even English. While these can be nice, they’re essentially pictorial flash cards in book form. If that’s what you’re looking for, they’re great, but they’re not stories.

As soon as you jump from “vocabulary books” to “story books,” however, something magical happens. “Magical” in the “holy crap, I’ve been studying Chinese for over two years and I can hardly read any of this book written for a 6-year-old” sense. One definitely gets the impression that these books are written not for the enjoyment of the young reader, but rather as the embodiment of the discovery that, “if we put pictures in these books, maybe we can trick even little kids into studying more characters and vocabulary in their free time.”

End results: (1) they’re way too hard for the typical Chinese learner, and (2) they’re not actually that interesting either.

One could be forgiven for thinking that maybe story books in electronic format are better. Sadly, they’re usually not. There are bilingual story books on the iPad, but most of them seem designed with the idea that either you want to read/listen to the story in English or in Chinese, but never both. As a result you have to start the whole story over if you want to switch languages. (And you may not even get pinyin, or have no option to hide it.) Not very learner-friendly.

Oh, and even on the iPad, there’s way too much of the 成语故事 (4-character idiom stories) mentality going on. In other words, “Oh, you want to learn Chinese through stories? OK, but only if the whole point is to memorize an obscure idiom. None of this time-wasting ‘using the language for your own enjoyment’ nonsense.”

But I’m writing this post not just to complain about a lack of stories. I’m writing to report that I actually did something about it. I created an app that houses interesting stories. Not “slight variation of the status quo” stories, but something radically different. I mean, one of the stories literally takes place in a post-apocalyptic steam punk world. With cyborg dinosaurs. And it was drawn and co-created by a local Chinese artist. (Ssshhh, don’t tell him that the Chinese are not known for their creativity.)

I think I did this partly to prove to myself that it could be done. (It turns out the Chinese language itself is not averse to fresh new story settings.) But also, this industry needs to break out of its 5,000-year-old mold and recognize that modern learners want more options. Sure, maybe “post-apocalyptic steam punk (with dinosaurs)” is not exactly the rallying cry of bored students of Chinese across the world, but this is a start.

So even if “post-apocalyptic steam punk (with dinosaurs)” isn’t your thing, even if “cute dogs causing chaos in the park” isn’t your thing, even if “the thoughts, voices and handwriting of modern Chinese college kids” isn’t your thing, I would at least hope that more interesting options for studying Chinese is your thing. And for that reason, I ask you to please try out the new Chinese Picture Book Reader for the iPad. (The app is free.)

Thanks, everybody!

03

Dec 2012No Sugar, No t

“No sugar” or “sugar-free” in Chinese is 无糖. The character 无, in its simplified form (not 無), is not particularly difficult to write. It’s barely more complex than “#.” The character for “sugar,” however, is a different story: 糖. Kind of complex.

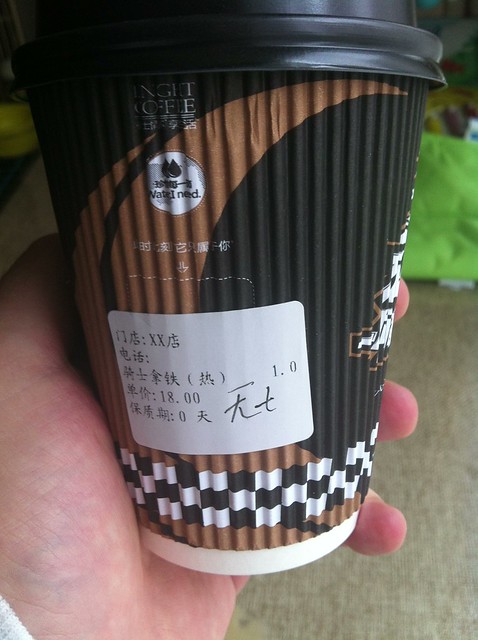

So if you’re working in a coffee shop and have to quickly mark coffee cups with a label that means “no sugar,” what are you going to use? Are you going to bother to write 无糖 over and over? Here’s what an employee at Knight Coffee writes:

So “无t” instead of “无糖.” (You can often see similar things going on if you can get a peek at the way that restaurant servers write down food orders by hand.)

Modern Chinese people grow up being equally familiar with the Latin alphabet and Chinese characters. Writing by hand is becoming less and important, and writing characters is sometimes seen as a burden. Typing on a computer can make it easier to type out complex characters (because you’re not actually writing out all the strokes anymore), and yet young Chinese people on the internet are mixing the Latin alphabet into Chinese quite liberally.

It does make you wonder how quickly we’re going to start seeing fundamental changes to the way Chinese people write. All languages change over time, although the written language often resists change much longer. But there’s a new catalyst in the equation this time: the internet.

Exciting times.

29

Nov 2012Japanese Fortune Cookies in China

As most of us in China know, fortune cookies are not a Chinese thing. They’re an American thing. ChinesePod just recently did a lesson on American Chinese Food, and user he2xu4 linked to this TED talk which gives more detail on the issue: Jennifer 8. Lee hunts for General Tso. (ChinesePod also once did a lesson on the fact that you can’t get fortune cookies in China.)

The thing is, it looks like now you can get fortune cookies in China. I took this photo in my local Carrefour supermarket:

OK, so it was in the “imported foods” section (they seem to be from Japan), but the packaging is in simplified Chinese. They come in two flavors: “cream” and “chocolate.” It says on the package: 装密语签语饼干, which means something like “Secret-containing Fortune Cookies.”

Probably the best thing about these fortune cookies, though, is that they feature Pac-Man. The Japanese may have had the invention of fortune cookies stolen by the Chinese in the United States, but at least as they introduce fortune cookies to mainland China they’re sneaking Japan’s home-grown video game icon into the mix!

26

Nov 2012What to Expect with Chinese Grammar

I’ve spent a nice chunk of my career on Chinese grammar, whether it’s explaining grammar structures in ChinesePod podcasts, working on the Chinese Grammar Wiki, or helping individual AllSet Learning clients. And two things that have become clearer and clearer to me are:

1. There are certain things that all learners struggle with at different stages of acquisition of Mandarin Chinese (this is consistent with the SLA concept of “order of acquisition”)

2. Most learners have no idea what to expect when it comes to the grammatical challenges that they’ll be up against (which can often make learners feel stupid for “just not getting it” immediately, not realizing that they’re struggling with something that all learners of Chinese struggle with)

To make a comparison with Spanish, most learners know from the beginning that they’re going to have to learn a bunch of verb conjugations for different tenses, gradually increasing in complexity over time. And beyond that, the subjunctive awaits. [Cue scary Spanish music]

OK, but what about Chinese? Many learners start with the patently false notion that “Chinese doesn’t really have grammar” or that “Chinese grammar is basically the same as English.” So they’re in for a fun little surprise there. This misconception doesn’t stand up long.

But beyond that, what is a learner to expect? The good news is that although different from English grammar, Chinese grammar isn’t horribly difficult. There are a few difficult points that deserve special attention, though, and I’ve created a new page on Sinosplice to point them out: Chinese Grammar Hurdles. The page is a rather simple list, but each point links to pages on the Chinese Grammar Wiki which have in-depth explanation (or will soon).

A few additional notes for beginners:

* Chinese word order isn’t the same as English word order. Sure, you can think of examples in which the word order is exactly the same. “I love you” = 我爱你, etc. But don’t expect that to hold true quite so neatly as you start adding in times, places, adverbs, etc.

* Particles are something new. Some of them, like 吗 and 吧, aren’t too difficult to get the hang of. Others, like 了, will actually take a long time to get a handle on. But that’s OK… you learn the different uses of 了 over time, and eventually it starts to gel, even if the accumulated understanding is not easily verbalized.

* Measure words are also something new, but they don’t need much attention at first. This is because you can actually get by for quite a while using the general-purpose measure word 个. So if your Chinese teacher is totally drilling you on all kinds of measure words when you just started studying Chinese, something is wrong. Learn the mechanics with 个, but focus on language more central to basic communication before focusing on expanding your measure word vocabulary.

Good luck in your studies of Chinese grammar! Although some things feel weird and arbitrary (as with any foreign language), Chinese grammar also has a strong thread of logic running through it that you’ll start to appreciate the deeper you get. For many learners, it’s a source of great satisfaction. Hopefully knowing what to expect with Chinese grammar will help you stick with it for the long haul.

20

Nov 2012CIEE Conference: Tech and Chinese

Over the weekend I joined the CIEE Conference in Shanghai. It struck me as a mini-ACTFL (but in town!), focused on study abroad. I was part of a panel discussion on “Effective Use of the New Digital Chinese Language Technology,” chaired by David Moser and also joined by Brendan O’Kane.

To sum up our initial points (and apologies if I get any of these wrong), what we said was:

– David Moser: Chinese used to be a huge pain because looking up words was so difficult, but now, thanks to technology a lot of the pain is gone

– Me: Technology is not inherently useful, but there is now great potential for a new, student-led way of learning enabled by technology

– Brendan O’Kane: both the level of students entering Chinese translation classes and the quality of Chinese reference materials are going up, but there are still some fundamental reading/parsing issues that need special attention

After we made our points, the discussion turned to a bunch of learning resource name-dropping, including FluentU, Shooter, and the Chinese Grammar Wiki.

Fielding questions from teachers and program directors, some of the issues that struck me were:

1. It’s not at all clear what resources are most useful to teachers (even ones like Pleco that have been around for quite a while and have a good name in the space) and which ones they can use

2. Even if teachers are willing to use new tools to find interesting, up-to-date material for their students, they don’t feel well-equipped to do so in anything resembling a systematic manner

3. What technology is here to stay, and what is just a passing fad? It’s hard to say. I don’t blame some of the teachers for wanting to just wait until the dust settles.

There are so many opportunities for innovation in this space right now…

13

Nov 2012Avoiding Meat in China (video)

Annie and the Shanghai Veggie Club have created a new video alerting vegetarians to some of the challenges you’ll face trying to eat vegetarian in China. It includes the language you’ll need to ask for what you really want:

(Yes, I know, for a vegan-friendly club, you’d expect a video with less cheese!)

09

Nov 2012Animal House for Studying Chinese

We’ve been doing some video clip dubbing experiments for fun on the AllSet Learning YouTube page. We started with Downton Abbey, and did Dracula for Halloween. That one was a bit on the discouraging side (although what can you really expect from Dracula?), so we decided to do a much more upbeat one. The result is this classic clip from Animal House dubbed to be about learning Chinese.

Our intern Jack has been doing a good job and having a good time with this little experiment. He’s the “student” in the Dracula clip, and he conceived the Animal House clip (although our AllSet Learning teachers recorded that one). Good job, Jack!

Are clips like this useful as study material? Probably not, but if they give you a smile and get you listening to a bit more Chinese, they’re worth it. For sure, the ones learning the most are Jack the intern and our teachers. It gets them thinking about the limitations of certain forms of media, tradeoffs in production resources, and creativity applied to pedagogy. It’s a worthwhile investment for us as a company. (BTW, we post all our new videos to our Facebook page as well.)

Anyway, happy Friday! 中文!中文!中文!中文!中文!

06

Nov 2012Learning a language is like…

There are lots of metaphors floating around for language learning. Fortunately most of them accurately stress the need for time, exposure, and deliberate practice. Here are a few them:

“Learning a language is like…”

Source: It’s a metaphor.

– Learning a language is like learning a musical instrument. “Commitment is way more important than natural talent, which simply doesn’t exist for getting the basics and even a pretty good idea of both music and languages. It’s actually just an excuse used by those who both can’t and don’t really want to put real work in.”

– Learning a language is like losing weight. “You know how to do it, really. There are billions of dollars spent every year on products that claim to make weight loss and language learning fast, easy, and painless. But they’re all variations on the same theme. To lose weight, diet and exercise. To learn a language, study and practice. There aren’t any shortcuts.”

– Learning a language is like learning to dance. “Yes, learners who do not like to perform (such as in role plays) and are reserved, quiet, and not eager to interact with others are disadvantaged when it comes to language learning.”

– Learning a language is like learning a sport. “…One of the great lessons of my childhood was that no one has the right to be naturally good at anything. More there’s a particular pleasure that comes from becoming good at something which you kind of naturally sucked at.”

– Learning a language is like running a marathon. “You don’t wake up one day and think: ‘Dude, I’m totally going to run the marathon of Los Angeles today.’ No, running a marathon or any significant distance requires practice and a healthy lifestyle.”

– Learning a language is like peeing. “You always pee less than you drank: input and passive vocab will always outstrip output and active vocab. Input precedes and exceeds output. Never expect to drink a liter and pee out a liter.”

– Learning a language is like playing Soul Calibur. “The same goes for input – that is, blocking against incoming strings of attacks. At first it seemed chaotic, and I didn’t know whether the blows would be high, low, or come from the side. Soon the chaos become patterns; now at the beginning of an attack I know exactly what is coming. I can anticipate the incoming chunk of actions, and only need to consciously react to the minor details – just like French.”

Oh yes, and living in China is like an RPG. Other metaphors are welcome! Leave a comment.

02

Nov 2012Sapore di Cina for Chinese Learners

I’d like to call attention to a relatively new blog on learning Chinese by Furio from Italy. It’s called Sapore di Cina (“Flavor of China” in Italian), and the author has a lot of good ideas (in English). A lot of his recommendations are the types of things I tell learners as well, so if you like Sinosplice’s entries on learning Chinese, there’s a good chance you’ll like Furio’s blog.

The blog post that first got my attention was Learn Chinese online: 27 excellent free resources. It’s a good list, and since any list of this sort doesn’t stay up to date for long, it’s good to check it out now. I was happy to see the Chinese Grammar Wiki in Furio’s list of resources.

Recently Furio published ChinesePod Review – An alternative way to learn Chinese. I won’t deny that it’s a complimentary review of ChinesePod in general (and me in particular), but one of the good things about this review is the Furio calls attention to some of the more effective (and economical) ways to get the most out of ChinesePod.

I’ve added Sapore di Cina to my on short list of Chinese resources on Sinosplice. Check it out!

30

Oct 2012Halloween Vocab Challenges

I’ve always found it a bit tricky at first to talk about holidays in Chinese. The Chinese holidays involve these things that we just don’t have, so it’s not a matter of translation, it’s a matter learning what these things are and what they’re called. 红包, 粽子, 对联, 扫墓, etc. Fortunately, that’s a pretty interesting learning process most of the time (especially if you’re learning the stuff hands-on in China), so all is well and good there.

And then there’s explaining the western holidays to the Chinese. Sure, the Chinese already know a lot about western holidays, so frequently all you have to do is fill in a few of the gaps. The fun part of figuring out where the gaps are, and what misperceptions there are. I’ve always enjoyed this too.

Halloween (万圣节) seems to bring a few of its own challenges, however. The concept is easy for the Chinese to get: it’s a 鬼节 (a “ghost festival”). It’s the trivial things that tend to pose challenges here. How would you say the following in Chinese?

– What are you going to be for Halloween?

– Don’t forget to wear a costume.

– Why didn’t you dress up?

The concept of “Halloween costume” does not seem to have standard translations, and you can get different answers from different people. I’ve been down this road before, and it can get a little confusing. The key is to focus on the verb for “dress up” rather than on the noun “costume.” Here is some of the language I hear Halloween-happy Chinese young people using:

– 你要穿什么? This one is a little vague, because it just asks “what are you going to wear,” which might apply to any party.

– 你要扮什么? This one gets more into the costume/disguise theme, sort of like asking, “what are you going to dress up as?”

– 别忘了装扮自己。 Here we see the verb 装扮, which is probably the most appropriate verb for dressing up for some role, although it seems a little overly specific for everyday usage. But it literally means, “don’t forget to disguise yourself.”

The 扮 in 装扮 (“to disguise oneself”) is not the same one as in the phrase 怎么办; it’s the 扮 from 打扮, which is most often used to mean “make oneself up” or “deck oneself out” (for a night on the town). Or you fans of role-play might also know it as the 扮 from 扮演, meaning “to play a role.” (Indeed, the formal Chinese translation for “role-playing game” is even 角色扮演游戏.)

One thing is for sure: Halloween parties are a great occasion to learn obscure vocabulary! I leave you with a last question (in 2 flavors), which very well might come in handy if the Halloween parties you attend are anything like the ones I’ve attended in China:

– 你扮的是什么? “What are you dressed up as?”

– 你这是什么装扮? “What are you supposed to be?”