08

Nov 2013How to bridge the gap to real Chinese

Olle at Hacking Chinese just put up a new post called Asking the experts: How to bridge the gap to real Chinese. In it, he asks quite a few language learners/experts the question:

“How do you bridge the gap from textbook/classroom Chinese to real immersion?”

My answer:

The truth is that no materials–textbooks, podcasts, videos, whatever–are entirely appropriate for any individual learner. That’s why it’s essential that the active learner adapt all materials to his own specific needs. Obviously, a good teacher is a tremendous help in doing this, and any good Chinese lesson with a teacher will involve bridging the gap between the language introduced in the study material and the language the learner can actually put to use.

At AllSet Learning we spend a lot of time selecting the study materials most appropriate for a given learner. That way, there’s less “bridging” that needs to be done by teachers, fewer additional vocabulary words that need to be introduced, fewer outdated or irrelevant terms to be filtered out, etc. More time in the lessons can be spent practicing applying the material to real-life situations.

For the independent learner (especially in a foreign language context), this issue of selecting materials is a huge challenge, and it probably involves a lot of time sorting through potential material. Recognizing that most textbooks are pretty outdated (how many textbooks currently in use never cover the words 手机 or 网络?) is a good start. The big question is then whether or not the material is truly useful for you, the learner. Usually HSK word lists and chengyu stories are not the most useful material. Neither are blindly selected frequency lists. What material is going to get you talking to Chinese people the fastest, about the things you care about, adding to your motivation to keep improving? That’s the right material to study.

Definitely check out some of the answers if this topic interests you at all; there’s a lot of them, with lots of good points.

A lot of the answers are what you might expect, but I especially liked the response by Roddy of Chinese-Forums.com:

I think I’d warn against a mindset of “I’m immersed, therefore I’m learning.” We all know people who’ve spent years in what should be a perfect language learning environment, yet somehow fail to make much progress. What do they fail to do?

First I think is a failure to pay attention and absorb. What do people actually say and do in the situations you’re in? Sit near the counter in a fast food place and listen to how people order food, or how the cashiers shout the orders back to the cooks. Stand near the doors on the bus and listen to how people buy their tickets or ask the conductor how to get to wherever. Note how your colleagues greet each other and how age or status affects that. Adopt that language.

It’s kind of remarkable how people can fail to do this. I was in McDonalds once eating with another foreigner, who was complaining about how they never seemed to understand his order for fries and he always had to point at the menu. Somehow he’d never noticed everyone else was asking for 薯条 [french fries], not the 土豆丝 [shredded potato] he was requesting.

Again, there’s lots more in Olle’s original post.

06

Nov 2013The Chengyu Bias

Chengyu (成语) are the (usually) four-character idioms that any intermediate learner of Chinese knows about. By the time you get to the intermediate level of Chinese, you’ve heard lots about how many of them there are, and how richly imbued with Chinese culture they are, and how they’re wonderful little stories packed into four short characters. Oh, and there are literally thousands of them, so you better start memorizing.

But wait… why?? Why do intermediate learners of Chinese need to start memorizing chengyu so early when, as far as they can tell, they’re relatively rare in daily life? Is it more important to learn a list of four-character idioms than to get better at ordering food in Chinese? Or to talk about basic economics? Or to discuss modern social issues? Or even to finally get a decent grasp of the ever-elusive particle 了? Those tasks all involve the use of relatively high frequency vocabulary and require no chengyu. So why the chengyu urgency?

The Bias

Many students of Chinese are told by their Chinese teachers that chengyu are important. They take this advice to heart and dutifully start learning. They may enjoy the stories behind them, or they may not, but these students inevitably realize that they hardly ever come across these chengyu they’re learning in actual conversation or even readings.

The fact is that teaching Chinese to foreigners on any large scale is a relatively new thing, and as such, some kinks are still being worked out. Early efforts at teaching foreigners involved a lot of transference of educational methods used on Chinese children. Memorization of Tang dynasty poems, writing out each new character hundreds of times, and memorizing lists of chengyu long before they’re actually useful are time-honored traditions when it comes to teaching Chinese kids their native language. That doesn’t mean these methods are effective for non-Chinese adults learning Chinese, especially when basic communication is the goal.

The Four-Character Fetish

Despite their questionable usefulness, chengyu get a lot of attention. From an English-speaking perspective, so much fuss over chengyu seems a little strange. Maybe it would help to draw some analogies to English.

Some chengyu are relatively straightforward to understand, and the meaning can be guessed. These are sort of like many English idioms. Think “raining cats and dogs” or “a dime a dozen” or “barking up the wrong tree.” They’re interesting to language nerds, and kind of make sense. They can be fun, but they’re no substitute for basic vocabulary. Fortunately, they’re also pretty easy to understand once your Chinese is at a low advanced level.

Other chengyu are more cryptic because they involve words and word order from classical Chinese, and/or refer to specific stories from ancient China. These are the ones you typically cannot guess the meaning of, and if you don’t know them, you’re absolutely clueless as to what they mean. These are the ones that truly separate the men from the boys in terms of Chinese literacy, and educated Chinese often stump each other with obscure chengyu of this type. It would be more appropriate to compare these with Latin sayings common in highbrow English, like “carpe diem” or “et tu, Brute” or “quid pro quo.”

In short, this second type especially, when overused, comes across as a bit pretentious. This connection of chengyu to an elite education is no small part of the appeal, either to native speakers or to learners of Chinese as a foreign language.

No Special Treatment

In Chinese, chengyu are generally considered individual words. This may seem a little strange, and the definition of a Chinese “word” is a bit amorphous to begin with, but bear with me here. Chengyu sometimes serve as mini sentences, sometimes work as verbs or adjectives, but essentially function like four-character words. Sure, they often have a rich history and pack quite a semantic punch in a small package, but they’re still essentially words.

Since they’re words, it’s easily to apply standard linguistic analysis to them. Corpus analysis can tell us how common any given chengyu is, what types of texts it’s likely to appear in, whether it’s a high-frequency word, etc. And the thing is, chengyu are not high-frequency words, especially when taken individually. Some are definitely higher frequency than others, but compared with ordinary words, they’re essentially all low-frequency.

Now obviously I’m not trying to say that low-frequency words are worthless or not worth learning. But why should low-frequency words be prioritized over medium-frequency words simply because they’ve got the chengyu label? When you start focusing on chengyu as an intermediate learner, that’s exactly what you’re doing. As an intermediate learner, there’s still a ton of good useful medium-frequency words to get familiar with. Why should chengyu get preferential treatment? When you need the word for “ambulance” or “stock market” or “allergy,” having memorized a few dozen chengyu (that you’ve probably never used) are little consolation.

So learners, don’t avoid chengyu, but don’t learn chengyu just because they’re chengyu. Don’t give chengyu special treatment when you could be improving your ability to communicate in Chinese. Just think of chengyu as the low frequency words they are, and when you start to encounter them naturally, learn them. When the time comes, you’ll recognize their usefulness in context and will see them more than once. As an intermediate learner, you’ll occasionally come across high-frequency chengyu (I have my own chengyu top ten), but certainly not by the boatload.

The Caveat

If you really love chengyu, then I’m sure my advice won’t shake your passion. And learning a few can certainly be interesting.

Thanks to @saporedicina for motivating me to finally put this post up. See also Olle of Hacking Chinese’s post (we definitely see eye to eye): Learning the right chengyu the right way.

01

Nov 2013Credit Sinocism When Credit Is Due

I’m often to busy to give the info-packed Sinocism newsletters my full attention, but when I do, I often find really great stuff. I’ve also noticed a trend on Facebook and Twitter. It goes something like this:

1. Sinocism newsletter comes out, with a link to especially interesting story “X”

2. Sinocism readers click through to the story on “X,” love it, share it via Twitter and/or Facebook

3. The Sinocism readers who share “X” get Likes, retweets, comments

You see the net effect here? Sinocism is serving as an invaluable information hub, but it’s not getting credit for the major role it’s playing in the dissemination of China-related news. And the worst part is that the Sinocism readers aren’t doing it on purpose; they’re just using their social media like they always do, but the way the system is set up, Sinocism gets no credit.

I’m pretty sure I saw an example of this last week. There was a great article about Chinese surnames‘ geographical distribution in China that got a fair amount of attention: Mapping China’s Surnames 制图 “老百姓”. I admit, I tweeted it too, the “bad” way. I then saw lots of people I know on Twitter and Facebook sharing it, no credit. I strongly suspect Sinocism set off the rash of shares (but wasn’t credited).

There are two solutions, as I see it:

1. Sinocism needs to build its social media presence. Ugh, I feel a little slimy just using the phrase, and I can understand if Bill Bishop would much prefer to keep the endeavor as a blog and newsletter. (Sinocism does have its own (private) Twitter account and Facebook page, but neither are used or promoted much.)

2. Sinocism readers make an effort to credit the articles they discover through Sinocism when they share them on social media. (For example, you could add “via @sinocism” to tweets, or maybe even “#sinocism“.)

Here’s an example of #2:

'China's Spielberg' Feng Xiaogang Says Censors Are Holding Back Industry (Q&A) http://t.co/rUikwUxJuo via @sinocism

— John Pasden (@sinosplice) November 1, 2013

Comments welcome! I’ve also asked Bill Bishop for comment. Please also support the Sinocism China Newsletter however you can; it’s a great service.

29

Oct 2013Apps, Graded Readers, Wiki, Duolingo

Time for a personal update on some of the stuff I’ve been working on….

Over the weekend AllSet Learning’s Chinese Picture Book Reader iPad app (v1.3) was finally approved! I am repeatedly surprised by how much time and effort the creation and maintenance of an iOS app takes. Although the app itself looks great, this is clearly not the best way for developers… it really makes me yearn for HTML5 apps.

That said, I’m really happy with what we’ve done! Sinosplice readers actually contributed ideas for this app’s new content, some of which is free, and some of which is paid. We probably should have added a bit less all at once to this release, but there’s still some more coming. Details about the release are on the AllSet Learning blog post: Chinese Picture Book Reader 1.3.

I’m also putting a lot of time into my (sort of) new Chinese graded reader project, but I’m saving more details on that for a future update.

The Chinese Grammar Wiki continues to grow. We’re adding more sample sentences and more translations across the whole thing, and while it’s already quite extensive in its coverage, it’s also beefing up across the board.

One thing I’ve gotten into personally (for fun, but also research) is Duolingo. I’m trying it out as a purely iPhone experience, and I chose French because I know very little about it, and I know that pronunciation is a challenge. Man, I’ve got some opinions. That’s a future post too, though.

I’m staying super busy, but I have a big long list of blog topics that will see publication on Sinosplice sooner or later. Because I’m spending so much time working on my own projects, it can be hard to not want to blog about them all the time too, but that would get annoying to some of my readers. If anyone has specific questions about what I’m working on, though, let me know, and the answers might just become blog posts.

If you’re interested in updates about all these Chinese-related projects I’m working on at AllSet, please do sign up for the newsletter. We won’t annoy you, and we’ll keep you updated!

22

Oct 2013The Shaping of a Bilingual Child’s Reality

My daughter is almost 2 years old now, and as she talks more and more, not only is it a blast to see that this little crying pink thing has grown into a real human, but I’ve also got front row seats to the amazing phenomenon of first language acquisition. If you’ve never seen a kid acquire language from scratch, or have never seen it happen bilingually, there are bound to be a few surprises. It’s kind of messy, and sometimes it feels like a wonder that it even works.

The other night my daughter displayed what you might call “neat presentation” of linguistic mastery. She asked for some water by saying “please water.” I gave her some of mine, and I could tell by her expression that it was colder than she expected. “It’s cold, huh?” I asked her. She nodded her head, repeating, “cold.” “It’s cold water,” I said. She nodded, repeating, “cold water, cold water.” Then she looked at her mom, and exclaimed with joy, “冰水,冰水!” (cold water, cold water). Wow, she’s already becoming a little translation machine! It’s not usually quite so orderly as all that, though.

Then there’s the “little boy” and “little girl” case, which ties in nicely with the concept of linguistic relativity. I recently realized that my daughter didn’t know the words “boy” or “girl,” and didn’t know the Chinese for them either. This seemed a little strange to me, because I know that during the day her Chinese grandmother takes her outside a lot, and she plays with other kids. Shouldn’t she at least know the Chinese for 男孩 (boy) or 女孩 (girl) or 小孩 (child), if not the English?

Well, it turns out that no, she shouldn’t know those words, because she rarely hears them. What she was learning was actually a bit more complicated than all that. Every time she encountered another baby that was male and younger than her, she was instructed to call him 弟弟, the Chinese word that literally means “little brother.” For girls younger than her, it’s 妹妹 (“little sister”). For little boys older than her, it’s 哥哥 (“big brother”), and for little girls older than her, it’s 姐姐 (“big sister”). This is fairly typical for Chinese kids.

Of course, she doesn’t know the word for “man” or “woman,” either. She calls all women 阿姨 (that is, any female that’s not obviously still a child, much to the dismay of the 20-year-old young ladies she encounters), which traditionally means “auntie,” and all adult males 叔叔.

She especially enjoys identifying every 阿姨 (“auntie”) she sees, whether it be a woman on the street, a female mannequin in a store, or even a drawing of a woman in an ad.

Meanwhile, I’m lamely trying to remind her that there are English words for all these people, starting with “boy” and “girl,” and maybe it’s my imagination, but could it be she’s having a hard time accepting the words I offer because they don’t match her existing mental map?

More exposure is all she needs, of course… I certainly won’t make it any more complicated than that; I’ll just keep throwing natural English at her (I don’t speak to her in Chinese). But it’s certainly fun to watch her deft little brain running through these semantic mazes. With continued exposure, she’ll make it through, no matter what Chinese (or English) throws at her.

15

Oct 2013We All Scream for Bling-qilin

The Chinese word for “ice cream” is 冰淇淋 (bingqilin). [Somewhat annoyingly, it also has an alternate form: 冰激凌 (bingjiling), but we’re ignoring that one for the purposes of this pun.]

So from “bīngqílín” (冰淇淋) we get this:

Honestly, though, they could really be trying a little harder on the bling.

Via friend and ex-co-worker Jason, who’s new doing cool things at FluentU from Taiwan.

11

Oct 2013Classical Chinese through Chinese Texts

I have to give a quick recommendation to the readers out there that have been toying with the idea of learning a little classical Chinese: Chinese Texts. It’s actually more fun than you might expect.

Via Sinoscism, which offers this introduction:

> This course is intended for people who would like to learn how to read classical Chinese philosophy and history as expeditiously as possible. The professor is a specialist in early Chinese history. He is not a linguist, and offers no more discussion of grammatical particles and structures than is strictly necessary.

This may be true, but I find many of the grammatical explanations rather linguisticky. I don’t mind (and I’m sure they could be a lot more abstruse). I like how supplementary grammar examples given are short, to the point, and interesting.

Here’s an example:

> 而 ér

> This is one of the most common words in classical Chinese. It links phrases, not nouns. “And” or “but” is often a satisfactory translation. However, often the phrase preceding 而 is subordinate, so it should be translated as a participle indicating modification. Thus, in the first sentence of the Mencius, the King of Liáng says 不遠千里而來 “[You] came, not considering a thousand miles too far.” In such cases the first phrase describes a condition or background to the second, as in the English sentence “Peter, fully knowing the danger, entered the room.” In other cases the two phrases are co-ordinate, and the second phrase simply narrates what follows (from) the first.

This is also one of those little bits of classical Chinese that will help sophisticate your modern Chinese. We cover 而 on the Chinese Grammar Wiki in a number of patterns.

Another great example of classical Chinese common in written Chinese:

> 以 yĭ

> This character was originally a verb meaning “to take, to take up, to grab onto.” Thus “X 以 noun verb” would mean “X takes or grasps the noun and verbs,” hence “X uses noun to verb.” Thus 以口言 “speaks with the mouth (口 kŏu),” or 以心知 “knows with the heart/mind (心 xīn).”

> 以 also precedes verbs, in which case it usually acts as a conjunction meaning “in order to.” Thus 出門以見日 “to go out the door in order to see (見 jiàn) the sun,” 溫古以習之 “to review ancient times in order to become familiar with them.”

> One of the most common uses of 以 is in the phrase 以為 “to take and make, take and use as, take and regard as.” This phrase can also be divided to form 以 A 為 B, “to take A and make it into B, use it as B, regard it as B.” As the translations suggest, this action can be either physical—to take some object or substance and make it into something—or mental—to regard something as being something else. Thus 以木為門 “to take wood (木 mù) and make a gate,” 王以天下為家 “The king regards the whole world (天下 tiān xià) as his household (家 jiā),” 孔子以國為小 “Confucius considered the state to be small (小 xiăo),” 吾以為子不知之 “I thought that you didn’t know it.” This use of 以為, both as a unit and as separate words, is still common in modern Chinese.

(You can find 以 on the Chinese Grammar Wiki as well, of course.)

I’m just starting this online course (my education in classical Chinese is still spotty and very incomplete), but it came highly recommended by a friend, and what I’ve read so far I’ve enjoyed a lot.

08

Oct 2013The (Chinese) Alcohol for (Chinese) Alcoholics

Here’s another one for the “I can’t believe they named the product that” file (see also “Cat Crap Coffee“). This one has more of a cultural differences angle, with a little bit of translation difficulty thrown in for good measure.

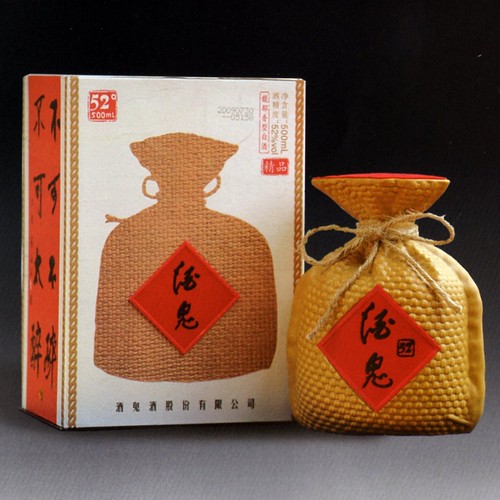

There’s a brand of Chinese rice wine called 酒鬼酒. Here’s a picture of it:

酒 in Chinese, while often translated as “wine,” more generally means “alcohol.” Traditionally, it’s some kind of grain alcohol, like 白酒 (Chinese “white wine“).

A person who routinely drinks to excess is called a 酒鬼 in Chinese, which literally means “alcohol demon” or “alcohol devil” or “alcohol ghost,” depending on how you want to translate 鬼. It sounds pretty negative, but in fact, in Chinese culture this type of alcohol abuse is not nearly so stigmatized. Although the police forces of many regions in China have begun cracking down on drunk driving in recent years, alcoholism in China is not as closely linked in the public consciousness to vehicular manslaughter, domestic violence, child abuse, and the host of other evils as it often is in the west. In fact, regular heavy drinking is closely linked to some of China’s greatest poets, most famously 李白 (Li Bai).

Here’s 李白 getting his drink on:

So it’s more in the spirit of historical drunken poetry (as opposed to inebriated abusiveness) that this brand of Chinese rice wine is called 酒鬼酒.

Translating the brand name into English is a new challenge in itself, though. If you simply translate 酒鬼 as “alcoholic” and 酒 as “alcohol,” you get “Alcoholic Alcohol,” which sounds like it means “Alcohol that Contains Alcohol,” which is just plain dumb. In fact, you can’t use the word “alcoholic” as a modifier at all for that reason, so if you don’t want to ditch the noun “alcoholic” altogether you have to say something like “Alcohol for Alcoholics,” which sounds like some kind of horrible demented “charity” to my American ears.

So what else can you do? “Booze for Boozers” and “Wino Wine” are ridiculous. “Drunk Spirits”? I’m curious what a creative translator can come up with. (Pete? Brendan?)

Anyway, 酒鬼酒 is a real company in China, and has its own Baidu Baike page (in Chinese, obviously), and is also listed on Wikipedia under “unflavored baijiu.”

03

Oct 2013Chinese Interbank Transfers Go Offline, and Alipay Swoops in

This National Day holiday (October 1-7), the People’s Bank of China (中国人民银行) is doing some major work on its computer system which handles interbank transfers, and as a result, interbank transfers will not be possible for the entire vacation.

It strikes me as totally ridiculous (and incompetent) that such an important part of China’s banking system would need to be down for so long. One could hope that it’s the last big push the country’s banking system needs in order to be completely modernized and never require this kind of downtime again for interbank transfers (or anything else), but I’m not quite that hopeful.

The amusing silver lining of this incident is that Alipay (支付宝, Taobao’s payment service) is taking advantage of the business opportunity and sending out its own marketing message: “hey, you can’t do regular interbank transfers during the October holiday, but if you try Alipay instead, no transfer fees!”

Pretty clever.

25

Sep 2013Bring on the Seed of a Free Internet!

Yesterday quite a stir was caused by an article on the South China Morning Post called EXCLUSIVE: China to lift ban on Facebook – but only within Shanghai free-trade zone. To be clear, though, it’s not just about Facebook:

> Beijing has made the landmark decision to lift a ban on internet access within the Shanghai Free-trade Zone to foreign websites considered politically sensitive by the Chinese government, including Facebook, Twitter and newspaper website The New York Times.

An unfiltered Internet? In Shanghai? Seriously?! For some of us, this is a total dream come true. I often say that filtered (and slow, as a result) Internet access in China is one of the most frustrating downsides to living in China as a foreigner. Maybe we should be more concerned about food safety, pollution, and social issues, but the truth is that Internet censorship directly affects us (and our businesses) every single day.

OK, but first, let’s be clear about what this so-called “Shanghai FTZ” really is:

> Shanghai Free-trade Zone is the first Hong Kong-like free trade area in mainland China. The plan was first announced by the government in July and it was personally endorsed by Premier Li Keqiang who said he wanted to make the zone a snapshot of how China can upgrade its economic structure. Other mainland cities and provinces including Tianjin and Guangdong have also lobbied Beijing for such approvals. The Shanghai FTZ will first span 28.78 square kilometres in the city’s Pudong New Area, including the Waigaoqiao duty-free zone and Yangshan port and it is believed it may eventually expand to cover the entire Pudong district which covers 1,210.4 sq km of land.

Photo by Will Change

OK, so it’s not all of Shanghai, it’s just a corner of Pudong. Bummer. But one could hope that such a haven of free internet access right in Shanghai could be expanded over time… or at least exploited by the entire city. It does give one hope.

Lastly, I’m reminded of a quote here:

> 百花齐放,百家争鸣 (“Let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend”)

Here’s hoping for the best!

Update: The People’s Daily has refuted the claims made by the SCMP article linked to above. Here’s some English coverage. Bummer, but I guess there’s no new “100 Flowers” incident brewing, at least!

19

Sep 2013Cat Crap Coffee

OK, so you’ve heard of kopi luwak, right? Just in case you haven’t, here’s some Wikipedia for you:

> Kopi luwak, or civet coffee, refers to the beans of coffee berries once they have been eaten and excreted by the Asian Palm Civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). The name is also used for marketing brewed coffee made from the beans.

Given the process by which this coffee is created, it’s not too surprising that we elect to refer to it in English by a foreign name–kopi luwak–rather than actually giving it a descriptive name. I mean, you can’t just call it “cat crap coffee,” charming as the alliteration may be, right? Well, you can in Chinese.

The Chinese name is 猫屎咖啡, literally, “cat crap coffee.” If you want to be a little cruder, the translation “cat shit coffee” is no less accurate.

What kind of blows my mind is that a coffee shop in the business of trying to sell this product (and it’s kind of expensive coffee) just straight up calls it 猫屎咖啡 (“cat crap coffee”). Don’t strain yourself too much with the marketing effort, right?

You can ask your Chinese friends if they’ve heard of 猫屎咖啡, and probably most of them have. What you won’t hear is them saying things like, “isn’t it weird that we just call it ‘cat shit coffee?'” Well, I have to hand it to the Chinese for calling a spade a spade.

But what I find even crazier is that there’s now a coffee chain expanding to multiple locations in Shanghai that goes by the very name “猫屎咖啡.” So some entrepreneur heard of this coffee, liked it, and decided he wanted the word “shit” in both his main product’s name as well as the name of his very business. Now that’s bold. Sassy, even.

The English name for the Chinese chain is, notably, “Kafelaku Coffee.”

Looks like there’s some backlash forming around this particular strain of coffee in the UK. I can’t imagine it’ll faze the Chinese market, though!

13

Sep 2013The California No and the East Asian No

I recently came across the term “California no” on Urban Dictionary. It is defined as:

> The way rejection tends to be handled by Californians, who are sunny in disposition and less brusque than East Coast residents. Instead of bluntly saying “no,” Californians say no by avoiding the question, forgetting to respond to emails, and generally postponing the issue. The best way to give a California no is to do nothing at all, as opposed to saying it outright.

> This is especially popular in the entertainment industry. For example, Everybody Loves Raymond creator Phil Rosenthal is quoted as saying: “To me, postponing a Hollywood lunch meeting is the new passing. They figure they’ll postpone you until you go away. This way, they are not saying no. If that happens more than twice — obviously emergencies come up — you’ve got to get the hint.”

> A: So I emailed that agent a week ago and still no response. What is going on?

> B: He’s giving you the California no.

This strikes me as very similar to the “Chinese no” (or even “Japanese no”): indirect, requiring the rejectee to “get the hint.” Anyone who’s ever studied “how the Chinese do business” will have read at least a full chapter on this topic.

Here’s a typical example taken from Chinese Business Etiquette: the Practical Pocket Guide:

> THE “NO” WORD

> Misunderstanding over the use of “no” is one of the most frequent causes of frustration in business negotiations. It is common knowledge that Chinese people do not like to say no.

> In accordance with Confucian ideals of humility and service, Chinese do not like to disappoint someone or seem ungenerous or unhelpful. The Chinese consider it rude to say no to someone even if that is the only answer possible. This cultural norm finds its most frustrating aspect in asking Chinese for directions. Should the person questioned not know what you are talking about, he or she will nevertheless give you false directions rather than appear unhelpful. Despite the wasted hours of wandering you may incur, remember they were simply being polite.

> Likewise, in business the Chinese will not usually come out and say no to a proposal directly. Instead they will give a vague response such as “perhaps,” “I’m not sure,” “I’ll think about it,” or “We’ll see”–all of which usually mean “no.”

What do you think, Californians? Are you culturally “more Asian” in this regard?

10

Sep 2013Chinese Character Picture Logo for “Yin Wei”

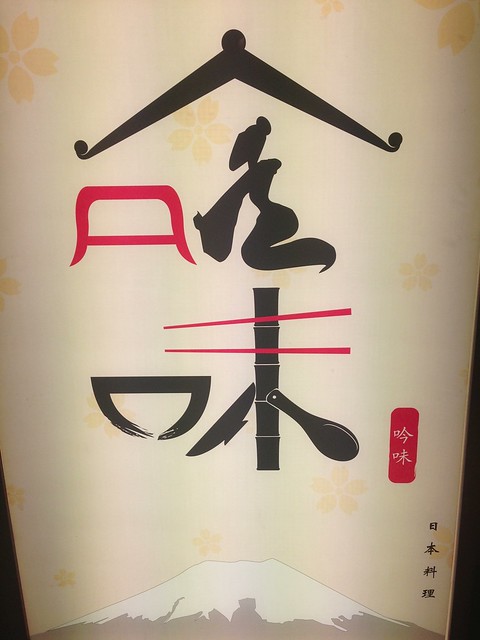

I definitely don’t like this logo as well as the 永久 logo, but this one is still noteworthy:

The Name

The name of the Japanese restaurant is 吟味. This is kind of a strange name to me; the only Chinese word I’m very familiar with that contains the character 吟 is 呻吟, which means “moan” or “groan.” It has numerous sound-related meanings, like “sing,” “chant,” and “recite.” 味, of course, means “flavor.”

In Japanese, I found an entry for 吟味 (ぎんみ) which means “testing; scrutiny; careful investigation.” I guess a name like that could be comforting in a country so beset with food safety issues?

The Pictures

I found it interesting how the mouth radical (口) is used in the same logo to form two very different pictures. The first one is of a table reminiscent of ancestral forms of the character 口, except upside down. The second one looks like a bowl, and although looking more modern, resembles a few of the other ancestral forms of the character 口 (and not upside down this time).

The right side of 吟 (the roof combined with the kneeling Japanese figure) to me really looks more like the character 令 than 今 in certain calligraphic styles.

Logos like this are interesting, but to me highlights an important point: Chinese characters are not pictures. They’re not even very much like pictures. If characters were really “like pictures,” this kind of logo wouldn’t work.

Certain Chinese characters and character components are historically pictographic in nature, yes, but you can see how even a basic pictographic element like the mouth radical (口) is actually very plastic. To me, what’s so fascinating about characters is not that they’re “like pictures,” but that they’re a ridiculously complex (and yet still viable) alternative symbolic system to alphabet-based writing systems.

I’ll write more on this subject later.

03

Sep 2013What is your staple food?

A while ago I was asked this question by Sinosplice reader Efraim Klamph:

I am teaching English in a somewhat rural location in Hunan. Sometimes students ask me, “What do Americans have as their main food?” I assume by “main food” they mean 主食, which Wenlin translates as “staple/principal food”. The concept of 主食 seems very clear in Chinese cuisine; particularly at the cafeteria where I eat, you get your veggies and meat all on top of a large serving of white rice. When I think of American or Western cuisine in general, I have a hard time thinking of what could serve as the 主食. Many of the students who ask me seem to be inclined that Westerners eat bread as their 主食. But think about the meals you eat when you’re back home; at least for me, it’s not always a bunch of vegetables and tofu served on a block of rice. So I say to the students that Westerners don’t really have a 主食, we sometimes eat bread, noodles and rice, but the concept of 主食 is rather different in Western cuisine. I mean, where’s the 主食 in the classic salad, hamburger and fries? Any thoughts on this?

Photo by beijingforbiddencity

I think when the Chinese think “主食,” they normally think “one kind of food,” whereas westerners often think of this as “a class of foods,” AKA what society in the States currently refers to as “carbs.” So our 主食 can be pasta, or bread, or mashed potatoes, or rice, or any of a number of things. Maybe even the hamburger bun and the fries. It depends on the meal.

It sounds a little ethnocentric to say that Western food has a rich smorgasbord of “主食” (carbs), whereas China has only rice. In reality, China does have quite a bit more variety than just rice.

Typical Chinese Carbs (主食):

- rice: 米饭

- wheat noodles: 面条

- mantou (steamed buns): 馒头

- glass noodles: 米线

- various “cakes”: 饼

- various dumplings: 饺子

Photo by rprata

Typical Western Carbs (主食):

- bread: 面包

- pasta: 意大利面

- rice: 米饭

- corn: 玉米

- potatoes: 土豆

Neither of these lists are exhaustive, but clearly there’s variation in the carbs consumed in both regions. The difference lies in the fact that certain regions of China stick much more closely to one type (e.g. rice every day in the south, noodles every day in the north), whereas more of a variety is typical in “the west.” More than once, I’ve had Chinese friends from the south tell me that they “just don’t feel right” if they don’t have at least some rice every day. It’s a seriously ingrained (ha!) eating habit.

Obviously, it feels kind of ridiculous to try to sum up the eating habits of “the west” so simply, even though your Chinese friends may very well expect you to do just that. So you may have to explain that in Mexico more corn tortilla and rice is eaten as the 主食, in Poland it’s more potatoes, in Turkey it’s various types of bread, etc.

But if you’re in China for very long studying Chinese and communicating with locals, sooner or later you’re going to have the 主食 discussion. Most Chinese have heard their whole lives that western food is very uniform and boring compared to the rich culinary tapestry that is Chinese food, so you can have a little go at shattering 主食 preconceptions with this one. (Good luck!)

29

Aug 2013The Yongjiu Bicycles Logo

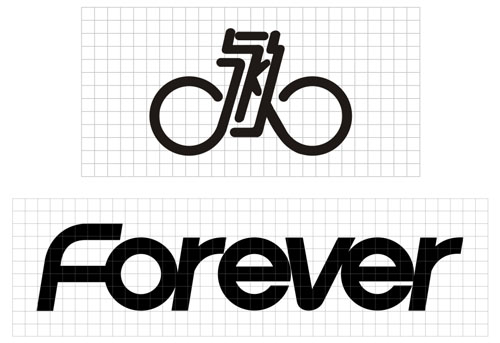

I noticed this cleverly designed logo for the Shanghai brand 永久 recently, and had to take note:

永久 means “permanent.” Here’s the logo with its English name, “Forever”:

Here’s a bit of evolution of the logo over the years (notice that it was once written right-to-left):

Finally, if you’re having trouble identifying the character elements in the logo, here’s a little deconstruction aid for you:

27

Aug 2013On Delayed Language Acquisition

JP recently finished studying Chinese at the Monterey Institute, and he said something that caught my attention:

> Ok, how’s my Chinese now? It’s better than when I started. I’ve certainly seen a lot of vocab and patterns. A few of them are in my daily speech now. I’m not terribly worried that I haven’t internalized more of those yet… it’s not my first rodeo. I know that some of that stuff will start coming out of my mouth in the months to come.

> I actually discovered this phenomenon when I got back from France in 1993. My French had improved tremendously from the immersion experience, and I had plenty of new frenchy habits. But I was a little disappointed that my French wasn’t even better. I would go to French class in Seattle and make a lot of the same mistakes I had made before. Oh well, I thought, I didn’t get fluent, but at least it was fun.

> Fast forward to a year later, and I was totally able to speak French. So apparently the growth came after I had returned, after the immersion experience was long over.

Of course there’s a big catch. You have to keep talking, keep practicing, keep trying to improve. That’s certainly no problem for JP, but some learners may think that all the magic happens in one special context at one special time, and once extracted from that special environment, all the learning stops. Not so!

The jury is still out an exactly how closely related first and second language acquisition are, but clearly the two are related. One of the things that gives me great pleasure is watching my (not-yet-two-year-old) daughter soak up new words, earnestly taking them all in, but refusing to repeat them. And then, days or weeks later, she’ll suddenly bust out with those words in the appropriate context, much to the amazement of her audience.

No, it’s not a deliberate show. Her brain needs time to properly “digest” what she’s ingested in order to put it to use.

For me personally, some of the most interesting phenomena relate to Chinese grammar. There are certain higher-level grammar patterns that you can learn, and know, and understand in context, but then just never use yourself in normal conversation. Why bother with something like 之所以……是因为 when you can just use the regular cause-effect pattern? Or why bother extracting the object and with a 把 sentence and moving it around when you can get by with a regular SOV sentence?

Mmmm, nuance. (photo by Merelymel13)

The answer, of course, is that all this stuff adds nuance. But you filter out nuance when you’re not ready for it. Then you marinate in nuance for a while before you’re ready to fully embrace it yourself. Then one day the nuance just pops out of you, expressing just what you meant, and you didn’t even know you had it in you.

To get to that point, you just have to keep accepting that input while continually giving yourself opportunities to communicate.

20

Aug 2013Text Message Fraud (a sample)

Photo by .sl. on Flickr

There’s a fair amount of text message (SMS) fraud going on in China, and if you have cell phone number here, you’re likely to receive this type of text at some point. As a foreigner, though, if you have trouble reading the text, you may get too caught up in trying to decipher what it says and forget to ask yourself, “could this be a scam?”

So here’s an example of a fraudulent text message I received just the other day:

> 我是房东,我换号码了, [This is the landlord. I’ve changed my number.]

> 你记一下,以后找我就打这个。 [Please write it down. In the future, you can reach me at this number.]

> 另外,这次租金请打我爱人卡上, [Also, this time please pay the rent to my spouse’s account.]

> 工行 621226.240200.6159780 [ICBC 621226-240200-6159780]

> 李敏,谢谢 [Li Min. Thanks!]

A few notes on what makes this text a little bit crafty:

1. The landlord’s changed his/her number. That’s why you don’t recognize the number. And you’re welcome to contact him/her at the number! Seems legit.

2. Oh, but now you have to send money. And the reason you don’t recognize the account is because it’s the landlord’s spouse’s account.

3. Here’s the kicker. The spouse’s name is Li Min (李敏). This is a deliberately gender neutral name (although it’s more likely to be a female name). The words for “landlord” (房东) and “spouse” (爱人) are also gender neutral. So whether your actual landlord is male or female, the message still works.

4. The spouse’s surname, Li (李), is not a coincidence. It’s #1 in the list of common Chinese surnames.

Don’t fall for this stuff, guys. I receive messages like this once or twice a month. They tend to follow a very similar pattern to the one above.

13

Aug 2013China, the Country of the Blind

Photo by Iris River on Flickr

I recently read H.G. Wells’ short story The Country of the Blind, and it immediately struck me how relevant this story is to western visitors of China in modern times. If you’re a China observer, and an observer of how westerners interact with China, it’s definitely worth a read.

If you’re too busy to read a short story (and it’s not overly sci-fi, for those of you not into the genre), you might check out the plot synopsis on Wikipedia.

Here’s an excerpt to give you a taste:

> “Why did you not come when I called you?” said the blind man. “Must you be led like a child? Cannot you hear the path as you walk?”

> Nunez laughed. “I can see it,” he said.

> “There is no such word as see,” said the blind man, after a pause. “Cease this folly and follow the sound of my feet.”

> Nunez followed, a little annoyed.

> “My time will come,” he said.

> “You’ll learn,” the blind man answered. “There is much to learn in the world.”

> “Has no one told you, ‘In the Country of the Blind the One-Eyed Man is King?'”

> “What is blind?” asked the blind man, carelessly, over his shoulder.

> Four days passed and the fifth found the King of the Blind still incognito, as a clumsy and useless stranger among his subjects.

> It was, he found, much more difficult to proclaim himself than he had supposed, and in the meantime, while he meditated his coup d’etat, he did what he was told and learnt the manners and customs of the Country of the Blind. He found working and going about at night a particularly irksome thing, and he decided that that should be the first thing he would change.

There really is a lot there to appreciate. Read the original.

On a related note, Kaiser Kuo has recently stated:

> On my podcast not long ago, Evan Osnos suggested that the best way to understand China today is to read Mark Twain—specifically “The Gilded Age” and “Life on the Mississippi.” Paul Mozur from the WSJ did just that and concurs. I’m now reading “The Gilded Age.” Yep.

Evan Osnos also recommends The Rise of Silas Lapham by William Dean Howells for the same reasons.

08

Aug 2013Coke’s Creative Campaign Can’t Hold Off the Tablet Wars

This big ad space in Zhongshan Park displayed massive iPad ads for the longest time, after which it was covered by Microsoft Surface ads. Just briefly, it was home to this Coke ad:

The ad reads:

> 和 型男 室友 老兄 神对手 一起分享可口可乐 (Enjoy Coca-Cola with stylish guys, roomies, old buddies, and arch-rivals.)

Coke is doing something creative with its labels this summer, using Chinese internet slang instead of the name 可口可乐 (Coca-Cola). Read more about this campaign here and here.

I noticed that as of this week, the ad space has been reclaimed by the Surface again.