24

Sep 2014Baidu Images Does Chinese Comics

I’m kind of used to Baidu copying almost every initiative that Google comes out with, so it’s always interesting to see what Baidu does that’s consciously different from Google’s way. One such thing is Baidu Images. You’re probably used to Google’s search-centric approach. While you can search for images on Baidu too, Baidu takes a much more curated, discovery-based approach to the home page.

Check out this screenshot:

Oh, also there are lots of pictures of pretty girls. No matter what you search for. Apparently that’s just a Baidu thing.

But also, there’s this “动漫” section now (indicated by the red arrow at the top). If you click on that, you get some kind of manga/anime directory at the top (I didn’t really look at this much):

But then if you keep scrolling down, you get an endless collection of Chinese comics! This is kind of cool. Here’s just a tiny selection:

But if you go to the 动漫 section of Baidu Images, you can scroll down forever. That’s a lot of comics!

16

Sep 2014Coloring without Rules

I recently gave a talk to some Chinese teachers about IB and AP Chinese programs in the US. In my research for the talk, I did quite a bit of reminiscing about my own 4 years in the Hillsborough High School IB Program. I had all but forgotten about “CAS hours,” and I seriously can’t remember at all what my “Extended Essay” was on. But one thing I totally haven’t forgotten about was “Theory of Knowledge.” That class was seriously cool!

It’s also a nice talking point for Chinese teachers, who are always eager to hear about how western schools systems foster creativity and independent, critical thinking. Theory of Knowledge fits in nicely there.

But the truth is that Theory of Knowledge would be far too little, too late if that’s all our school systems did to try to encourage independent, critical thinking. And it’s not exactly “creative” either. Those aspects of our western educations begin far earlier, even before we start school.

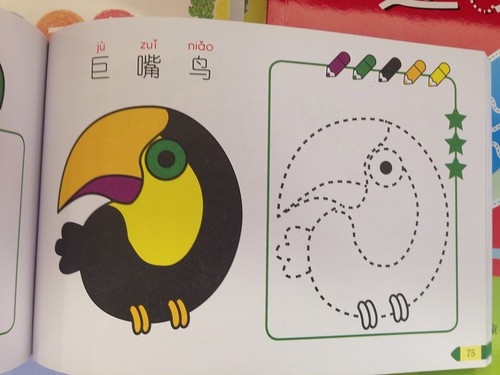

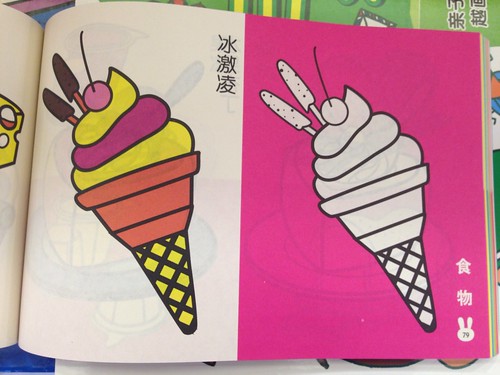

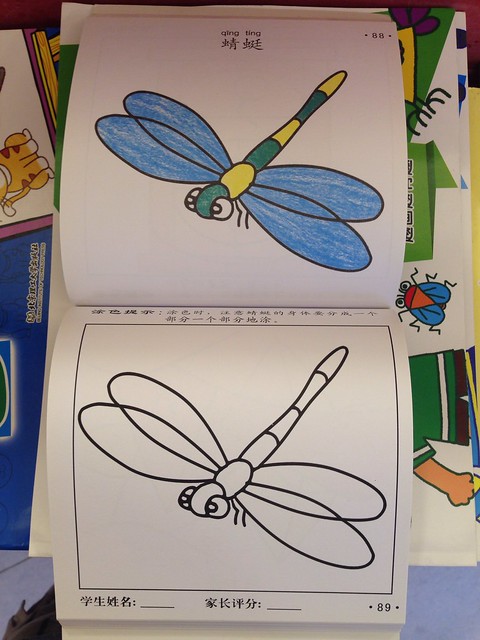

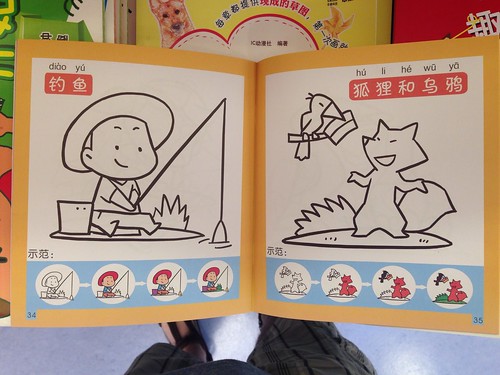

I was reminded of this the other day when I tried to buy a coloring book for my daughter. I had only two criteria: (1) it had to have lots of nice pictures to color (no text), and (2) it had to be cheap. Criterion #2 was the easy one. I had no idea I was apparently asking for way too much with #1. Take a look at what I found in the book store I went to:

Do you see a trend? In each book, the child is shown exactly how to color the picture. There’s a right way and a wrong way. (Oh, and also, you generally can’t just color without having new vocabulary forced on you.) I checked every single coloring book candidate in the children’s book section, and they were all like this. Not a single one just had blank pictures without “models” to follow. (Those models, by the way, waste a lot of space and paper, which could be more pictures to color.)

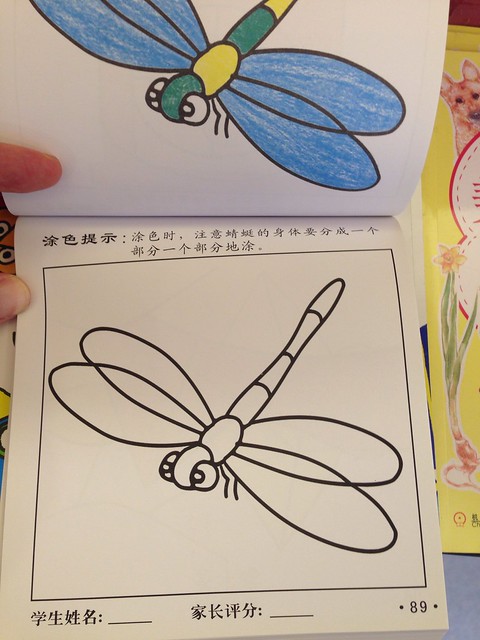

As if that weren’t enough, take a closer look at this picture:

At the top, that reads:

涂色提示:涂色时,注意蜻蜓的身体要分成一个部分一个部分地涂。

Translation:

Coloring reminder: When coloring, be sure to use different colors for the different parts of the dragonfly’s body.

Why can’t a 3-to-4-year-old just color the dragonfly all one color? Well, because dragonflies are never a solid color in nature, of course!

Oh, wait.

What’s even more heartbreaking is what’s at the bottom of that same page:

学生姓名:__________ 家长评分:___________

Translation:

Student’s Name:__________ Parent’s Score:___________

That’s right. If you’re going to color a dragonfly, you have to put your name on it and claim responsibility for your crayon crimes, and then stand judgment for the objectively right or wrong colors you have committed to that paper.

I can imagine the harsh frowny faces the publishers would give a child that artistically attacked one of their pictures, American-style, and ended up with something like this:

To be fair, the kind of coloring book I was looking for does exist in China. In fact, I’ve bought one before at our local Carrefour supermarket. I was expecting higher quality and more variety at an actual book store, but instead, all I could find was this prescriptivist nonsense.

This is only a post about coloring books. I really wish this were the biggest problem with the Chinese educational system.

08

Sep 2014A Pun for Mooncake Day

Today is Mid-Autumn Moon Festival in China, so here’s a little moon pun for you:

The first line is where the pun resides. It reads:

> 月圆月期待 [moon round moon looking forward (to it)]

This is pretty nonsensical because the character for moon, “月” has replaced the identical-sounding character 越. Most intmermediate learners will recognize this character as being part of the 越……越…… pattern.

So the meaning is:

> 越圆越期待 [The rounder it is, the more you look forward to it]

Still seems kind of nonsensical to me (in this context, anyway), but it’s just a lame pun for a billboard.

The brand an product is:

> 元祖雪月饼 [Ganso “Snow” Mooncakes]

Happy Mooncake Day!

03

Sep 2014Confidence and Tones

It was in the summer of 2012 during a talk with all-star intern Parry that I first discovered that confidence-based learning was a thing. The concept had occurred to me before, but it really gelled when I saw this graph:

Confidence-based learning applies to any kind of learning, but I think it applies especially well to mastering the tones of Chinese. Let’s take a quick walk through the four quadrants of the graph above…

- Uninformed. So this is your typical beginner. You don’t know much, and you know that you don’t know much. It’s hard to say much of anything, and tones are only a part of the problem. Obviously, study and practice are needed.

- Misinformed. In this case, the learner has learned a lot of Chinese, but has either not had sufficient practice, or has gotten bad feedback, leading him to believe that his tones are much better than they actually are. Part of the problem may be Chinese speakers’ tendency to overpraise any ability to speak at all. If no corrective feedback is ever given, how will the learner know his tones are still in need of work? This is the “unjustified confidence” I’ve talked about before in my post Laowai Delusions of Fluency. It helps to stay humble, and honest feedback is essential.

-

Doubt. If you’ve learned to be humble, and worked hard at improving your tones, they may be pretty good. But you may still lack confidence. You may speak quietly, or try to rush through words you’re not 100% sure of the tones for. This is actually a pretty good place to be, because you have the knowledge, and you just need some extra practice and corrective feedback. You’re probably used to not getting any feedback, which results in the doubt.

-

Mastery. You may not be perfect, but you know you’re pretty good, and you can speak with confidence. You know your tones, and you can pronounce them correctly. This doesn’t happen in a short amount of time; it comes as a result of extended practice with good feedback.

You need to KNOW the Tones

A friend once asked me what the correct tones were for a certain word. I told her: “3-2” (or something like that).

She then looked at me and asked, “how can you just do that? How do you know the tones for so many words?”

“I memorized them,” I said.

This is not the answer she wanted; she hoped there was some trick or pattern she could learn. There is another option of course: to learn like a child. Children, immersed in the language environment don’t “memorize” tones per se; they hear them so many times that there’s only one “natural” answer. This isn’t realistic for most adult learners, though, who frequently have to go from dictionary lookup to written or spoken communication. You have to know the tones of the vocabulary you know, and then you have to be able to correctly pronounce those tones.

This knowledge of tones corresponds to the “knowledge” axis of the graph above.

You need to be able to PRODUCE the Tones

Confidence in tonal production comes from the knowledge that you can consistently and correctly pronounce the tones correctly. This starts with being able to produce the tones of single syllables correctly, and then later progress to being able to produce tone pairs correctly, and eventually extends to longer phrases and whole sentences. But you need to practice, and you need good feedback. You need to know when you’re right and when you’re wrong in order to progress and gain that confidence. (See also The Process of Learning Tones here on Sinosplice.)

The way that we build confidence in tonal production at AllSet Learning is through regular pronunciation practice with a teacher (almost every lesson, for about 10 minutes). This is important well into the intermediate level. We have developed our own exercises for this, which are available online as Pronunciation Packs.

At this point in history, I don’t recommend computer feedback to work an tonal production. Perhaps some tonal feedback is better than none, but human perception is a weird thing, and computers do “logical” things which seem extremely strange to humans sometimes. Right now, only humans can reliably tell us how good tones sound to humans. Maybe someday that will change.

So build up your knowledge of tones, and get some good practice with corrective feedback to build your confidence. Mastery awaits.

26

Aug 2014Pronunciation Practice: the next Evolution

I’m really exited to announce that AllSet Learning now has its own Online Store. After releasing several new products on Apple and Amazon’s platforms in recent years, I’ve discovered that those channels can sometimes be more than a little “challenging.” But those platforms don’t support all of AllSet Learning’s ambitions. Some of the things I want to do won’t be realized even in the next few years, but others can be broken down into simpler units that people can use right now to improve their Chinese. AllSet Learning clients have been benefiting from some of these for years already. And those are what we’re putting in the new store first.

The title of this post is “Pronunciation Practice: the next Evolution” referring to Sinosplice’s own Tone Pair Drills. We actually used those with AllSet Learning clients in the very beginning, and they worked pretty well, but we wanted to keep improving on the concept. Over the years we tried some things that didn’t work so well, and others that worked great. Each client had different needs, so a modular approach made the most sense. We’ve organized the best of these different drills into “packs,” added professional-quality audio, and it’s with that material that we proudly launch our new store.

If the idea of pronunciation practice is boring to you, I can sympathize. As a student, I totally blew off my “mandatory” language lab sessions, and still got A’s in my Chinese classes. But I had to pay later when I arrived in China and people actually couldn’t even understand me. That was the real wakeup call: pronunciation matters. Besides the occasional reminder, AllSet Learning clients do a regular pronunciation practice over an extended period of time to achieve dramatic progress.

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: pronunciation practice in Mandarin Chinese should be a regular part of any formal study, starting from day 1 and extending well into the intermediate level. Two weeks on pinyin at the start of a beginner course is far from sufficient, and it’s rare than an intermediate learner wouldn’t benefit from tone pair practice or other focused pronunciation exercises. So clearly, this is an aspect of Chinese study materials that could could stand a little expansion.

Thank you, Sinosplice readers, for the support you’ve given AllSet’s endeavors in the past. As a thank you for your readership, I’d like to offer this 20% discount voucher to Sinosplice readers (valid for 3 days):

> IREADSINOSPLICE

Thanks for visiting the AllSet Learning Store and checking it out!

21

Aug 2014Summer Nap in Jing’an Park

I couldn’t resist snapping this picture in Jing’an Park:

It’s been an unusually short/cool summer in Shanghai. I guess that makes it easier to fall asleep in public with utter abandon? (But then, Chinese people are typically pretty good at that…)

19

Aug 2014Boring Small Talk is an Opportunity

At AllSet Learning, I hear about a lot of different learner problems. One of the more common ones from intermediate learners is, “I just keep having the same boring conversations over and over again: where are you from, how long have you been in China, are you used to eating Chinese food, etc.” Learners tend to see these limited, unchallenging conversations as contributing to the intermediate plateau they are on.

(Side note: not too long ago, these same learners were likely struggling to get Chinese people to talk to them in Chinese, so from that perspective, this problem is a good one to have!)

There are two things I say to these learners:

- You’re being too passive. Here you have a friendly, willing conversation partner, and all you can do is sit back and let them pick the topics from the same old boring set?

- The small talk is just a signal. They’re trying to tell you they are willing to talk to you, and you’re wasting a good opportunity with your passiveness.

You can’t really expect a Chinese person to outright say to you: “Hey, I’m interested in you! Let’s talk! You can talk to me about anything you want.” So what does it look like when a Chinese person conveys this same information with other words? It looks exactly like boring small talk. So when you start getting hit with boring small talk, take it to mean this: “Hey, let’s talk! I can’t think of any good topics, though, so I’m going to throw boring topics at you until either you get brave enough to start a real conversation, or we both tire of this.“

That’s a lot better, isn’t it?

Now about being too passive… All you have to do is keep a few interesting questions handy to pull out when you are in this kind of situation. Sure, not every situation is appropriate… You might be more willing to ask a cab driver about bizarre things than your girlfriend’s aunt. But at least have them ready for when you are “prompted” the next time. Keep updating your questions if you find certain ones are getting old.

- Is Mao your hero?

- What’s the best foreign food you’ve ever had?

- What do you think of India/the USA/Japan/Israel?

- What do you think of religion?

- Do you give money to beggars? Why or why not?

- Do you play games on your cell phone? What games?

- Do you believe aliens exist?

Here are a few examples of what I’m talking about:

Yeah, some of them are a little serious or weird, but those tend to have one of two effects: (1) they stop talking to you (no more boring small talk!), or (2) you get an interesting perspective from them.

Good luck!

13

Aug 2014Pip & Estella

Hypothetically speaking, in a rewritten Chinese version of Great Expectations which takes place in modern China, Estella’s name should definitely be 冰冰. But what about Pip? Suggestions welcome! (His name in the typical Chinese translation is 匹普, which is horrible, and we’re certainly not using.)

(I will neither confirm nor deny that this question is related to Mandarin Companion‘s next release, which may or may not be the first Level 2 book.)

05

Aug 2014Why You Won’t Learn Like a Child

It’s not that you can’t learn like a child, it’s that you won’t. You’re not willing to. Not because you aren’t committed, or aren’t smart enough, but because you’re an adult with a little bit of self-respect. And you get frustrated.

Have you ever hung out with a crazy friend who will go up to any stranger and say anything, seemingly without inhibitions? It’s awkward but also awe-inspiring, because it opens your eyes to how much your own inhibitions prevent you from doing and experiencing. This is sort of how I feel about my daughter as I watch her simultaneously acquire English and Chinese. Like all toddlers, she is awesome in so many ways that I feel that 99% of adult learners will not let themselves be.

You want to acquire language like a child? Here’s a list of things to do.

- Be told something is useful. Shrug it off and discard it because it’s boring and tackle something fun. [I see learners of Chinese tackle the HSK word list every day because they see it as “useful.” A child would not do this.]

- Say something wrong. Be corrected. Say the same thing wrong again. Be corrected. Say the same thing wrong again. Be corrected. Etc…. and yet never lose the desire to keep communicating. [This is perhaps one of the most amazing things that kids can pull off. They know no shame, feel very little frustration, and when it comes to language-learning, that makes them invincible. They’ve never learned a language before, so have no idea “how they’re doing at it,” and don’t care.]

- Ask how to say something, forget two minutes later. Ask again. Forget 3 minutes later. Ask again. Forget one minute later. Ask again. Etc…. [Adults, quite simply, get quite embarrassed when they keep forgetting something that they feel they should be able to remember. Everyone has a limit, and eventually adults will get too embarrassed to keep asking.]

- Say something simple. Repeat it. Again and again, until your conversation partner is visibly agitated. Do the same thing the next day. You’re locking that in.

(Yeah, I’m in the middle of a non-sensical conversation with my mom, but she’ll wait.

photo: mliu92) - Repeat something that you’ve just been told in order to confirm it. Then do it again. And again. Because why not do a triple or quadruple confirmation? You’re locking that in too.

- Say a word wrong, and get corrected on your pronunciation. Try to say it correctly, but fail. Shrug it off and doggedly continue with your incorrect pronunciation for now, because you know they understand what you mean (and hey, you’ll get it eventually!).

(Stop. I call it “pasgetti.” Now you just deal with that, and let’s move on.

photo: sesameellis) - Ask how to say something. Discover the word is hard, and just dismiss it, as if you never really wanted to learn it anyway. Give your dad a withering “I’m going to pretend you didn’t just say that” look. [Adults will sometimes postpone difficult vocab, but very often, they’ll bite off more than they can chew rather than “retreat” and live to fight another day. My daughter repeatedly dismisses the English word “electricity.” In Chinese, “电” is easy.]

- Tell your teacher super basic information all the time that your teacher obviously already knows. It’s like telling your Spanish teacher how to conjugate “estar,” or telling your math teacher about the Pythagorean Theorem. [They don’t need you to tell them this, but telling them helps you.]

- Talk and talk, even though you know you’re not making any sense. Use body language, tone of voice, and context to communicate something, anything. Then wait for the listener to try to make sense of that train wreck of a message, and just take it from there. Feel no shame.

- Make so little sense when you talk that you confuse your listeners. When they express their confusion, laugh at them. Then continue to not make sense if you feel like it.

If you can do all these things as a language learner, then congratulations! You are a rare learner indeed (or maybe roughly three years old?). You will learn quickly (if you don’t get shunned by too many native speakers for not acting “normal”).

But even if you can’t do these things, adults have lots of advantages over children, and no one expects you to learn like a child. Different ages call for different learning strategies. (But it doesn’t hurt to be just a little reckless in your learning, either.)

29

Jul 2014The Beauty of Chinese Numbers

The beauty of Chinese numbers is that they are consistent. You learn the rules, and they just work. Even if you try to get flippant and say 一十 for “10” instead of just regular old 十, no one’s going to get upset.

The consistent beauty of Chinese numbers is made all the more obvious by the relative skankiness of numbers in English. I noticed this because my daughter (now somewhere between 2½ and 3 years old) has pretty much mastered all the numbers to 100 in Chinese, but the teens in English continue to stump her. She can count to 20 no problem, but if you ask her to read a random two-digit number that starts with “1” in English, that’s where the trouble starts. If she’s speaking Chinese, she can read either Arabic numerals or Chinese characters all the way to 100, but doing it in English trips her up especially for the range 11-20. She’s actually much better in the 60-90 range, because they’re regular.

If English numbers were totally regular like Chinese, we’d see these little gems (pretty much all of which my daughter has tried to pull off at one time or another):

– 10 = Onety

– 11 = Onety-one

– 12 = Onety-two

– 13 = Onety-three

– 14 = Onety-four

– 15 = Onety-five

– 16 = Onety-six

– 17 = Onety-seven

– 18 = Onety-eight

– 19 = Onety-nine

– 20 = Twoty

– 30 = Threety

– 50 = Fivety

Somehow I missed it my whole life, but one of the things that makes the names of the teens so bizarre (aside from the inexplicable “eleven” and “twelve”), is that the digits are represented backwards, only for these 7 numbers. When you see “36” and read it “thirty-six,” the “thirty” corresponds to the 3 on the left, and the 6 to the “six” on the right. So you’re reading the number, digit by digit, left to right. But for numbers like 14, 15, and 16, not only do they sound like 40, 50, and 60, but the order of the syllables better matches 40, 50, and 60 as well. And both the “-ty” and the “-teen” from those numbers originally represented “10,” right? These pairs are essentially pronounced as if they were the same numbers! Confusing as hell. I feel for my daughter.

Fortunately kids don’t realize they have good reason to be frustrated, and just jeep on truckin’.

24

Jul 2014Clean Water in China?

Last week AllSet Learning staff took a team-building trip to the mountains of Zhejiang in Tonglu County (浙江省桐庐县). It was a nice trip, and one of the things that struck me most about the natural beauty there was the lack of litter and crystal-clear water. Anyone who has traveled much in China knows that it’s a beautiful, beautiful country, but disgracefully covered in litter in so many otherwise breath-taking tourist destinations. Not so in Tonglu!

I was also surprised to learn that the locals there drink the water straight from the mountain streams without treating it at all. They don’t have “normal” plumbing, it’s all piped from the higher regions of the flowing mountain streams. I have to wonder: with so much of China so heinously polluted, could this water actually be safe to drink?

Anyone else want to weigh in with some facts or links?

22

Jul 2014The 4th Ayi: Chinese Girls’ Nightmare

We learners of Chinese typically learn that “ayi” (阿姨) means “aunt,” and then soon after also learn that it is also a polite way to address “a woman of one’s mother’s generation.” Then, pretty soon after arriving in China, we learn that it’s also what you call the lady you hire to clean your home. (The last one tends to become the most familiar for foreigners living in China.)

Today I’d like to bring up a fourth use of “ayi” which kind of circles back to the first one, but is also subtly different, and additionally extremely interesting in the way that it makes young women squirm in social discomfort. This is the use of “ayi” that you really only learn if you spend enough time around young (Chinese-speaking) children in China.

Many terms for family and relatives are used quite loosely in Chinese to show familiarity or politeness. The way it works for little kids in China is something like this:

1. Little girls that are older than you are called “jiejie” (姐姐); little boys that are older than you are called “gege” (哥哥). Often this is a two-year-old calling a three-year-old “gege,” or even a 17-month-old calling an 18-month-old “jiejie.” That’s just how it works.

2. Little girls that are younger than you are called “meimei” (妹妹); little boys that are younger than you are called “didi” (弟弟). Again, the age difference might be tiny; it doesn’t matter. Even for twins, the older/younger aspect of the relationship is strictly acknowledged.

3. Here’s where it gets interesting… To a little kid, if you’re female, but are no longer a child, you’re suddenly an ayi. This often violates the “mother’s generation” rule that we learn in Chinese class… If the kid’s mom is 34, the kid is usually still going to call a 20-year-old girl “ayi” because a 20-year-old is obviously not a child. (Note: this is largely based on observations in Shanghai; use of the term may vary somewhat regionally. China is a big place!)

But this is where it gets very amusing to observe… a lot of 20-year-old girls have never really been called “ayi” before and they hate it. It feels like they’re being called OLD. In very recent memory, they may have had younger cousins calling them “jiejie,” but now this little kid is suddenly pronouncing them NOT YOUNG ANYMORE. A lot of these 20-year-old girls will correct the little kid that calls them “ayi,” telling the kid to address them “jiejie.” Most of the time the kids will have none of it, though. You can see it on their faces: “What? You’re not a little kid. You’re clearly an ayi.”

So yeah, I’ve been observing my toddler calling strange young women “ayi” and watching these young women freak out. And yes, it’s pretty funny to me.

So, to sum up, the four meanings of “ayi” (阿姨):

1. “Mother’s Siter” Ayi

2. Middle-aged “Ma’am” Ayi

3. Housekeeper Ayi

4. “I’m a little kid and you’re not” Ayi

If you’re in China and you’ve never noticed it before, be on the lookout for #4. It’s easy to spot, because it usually involves a young woman in her early twenties approaching and fawning over a cute little kid, then the inevitable offensive “ayi” term is used, the failed attempt at “jiejie” persuasion, and the young woman walking away pouting.

15

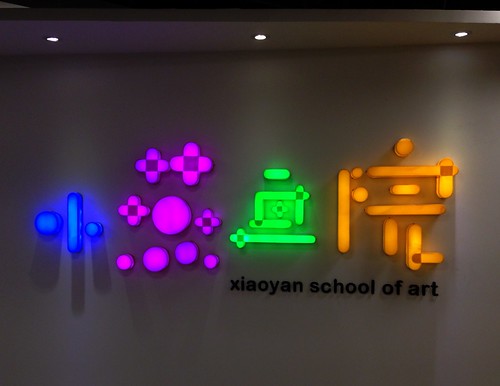

Jul 2014Abstracted Characters

Stylized letters and characters are interesting to me, but how abstract can you get with Chinese characters? You kinda have to retain the strokes and radicals and stuff, right? Maybe not…

The characters represented above are 小燕画院.

Although the name is readable, it might take a bit longer to decipher than most Chinese text, even for native speakers. Have you ever spotted characters that have been taken even further into the abstract?

09

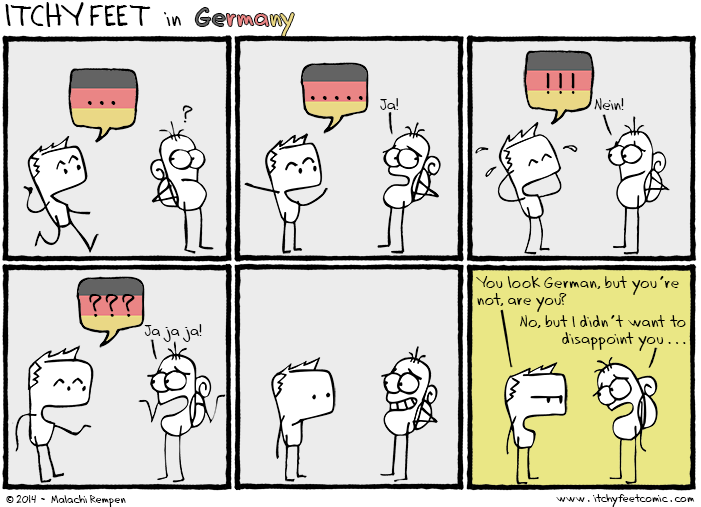

Jul 2014Itchy Feet on Communication

The webcomic Itchy Feet has some great comics on learning to communicate in a foreign language. I especially like his visualization technique for representing a low level of competency in a foreign language. These are about German and French, but could be about any language, really:

This one will feel relevant to ABCs in China:

Itchy Feet is also the comic that did this amusing take on various Asian scripts which went semi-viral a while ago:

04

Jul 2014Baijiu Bigotry

I recently saw a link to this article on Facebook: One Billion Drinkers Can Be Wrong (China’s most popular spirit is coming to the U.S. Here’s why you shouldn’t drink it). So it’s a post laegely about how baijiu (白酒) cannot success outside of China because it’s a terrible, terrible liquor. (Some of the comments I read on Facebook went much further, and I’ll address that sentiment below.)

Now I’m no fan of baijiu; I’ve made this clear in the past. And when I say it’s terrible, I know it’s because I personally will never develop a taste for it, and I’m not interested in “giving it a chance.” I’ve done that. Plenty of times. (Same goes for chicken feet.) I think part of it is that I resent a certain idea that sometimes gets tossed around: if you’ve been in China this long, you should have learned to like baijiu by now. Nope, sorry. Don’t like it. Now leave me alone.

But I’ve also learned–thanks to my friend Derek Sandhaus–that it is possible for westerners to develop a taste for baijiu. I seriously doubt it’s ever going to go mainstream, but the Chinese will ensure that there’s always a market for the stuff.

The article linked to below, though, goes way beyond the idea that the Chinese like it and westerners typically don’t. It reminds me of Seinfeld’s “chopsticks bigotry” (which is actually funny, because it’s a bit more self-aware):

> I’ll tell you what I like about Chinese people … They’re hanging in there with the chopsticks, aren’t they? You know they’ve seen the fork. They’re staying with the sticks. I’m impressed by that. I don’t know how they missed it. A Chinese farmer gets up, works in the field with the shovel all day… Shovel… Spoon… Come on… There it is. You’re not plowing 40 acres with a couple of pool cues….

What’s interesting about this type of opinion of baijiu is that this is a truly dividing issue. Some westerners will actually hold the opinion that “this is a vile alcohol and no one should drink it, Chinese or not.” You might hear some cross-cultural statements of the some ilk about peeing in public, or disregard for safety, but attacking another culture’s favorite alcohol? It’s just a bit bizarre.

What do you think?

01

Jul 2014Grammar at 2½: a quick update

I enjoyed writing the post about my daughter’s mastery of Chinese grammar at age two. It wasn’t scientific, but it was an interesting study for me nonetheless.

This just a quick update, because I was wondering when my daughter would start getting into the “harder,” intermediate-level B1 grammar points. Well, I’ve got an answer now.

Right around the time she turned two and a half, we had soft tacos for dinner, and she busted out with this sentence:

> 我要把它包起来。 [I want to wrap it up.]

This short sentence is significant because it features both:

1. The 把 sentence structure

2. The 起来 complement

[Mind blown]

From the original “cannot use” list, the only other one she’s picked up has been personal pronouns (which she’s still getting used to). I really thought it would be a while before I heard 把 come out of her mouth. She’s definitely not using 把 often, but it’s already in that little brain…

27

Jun 2014Thoughts on Scott Young’s Immersion Experiment

I recently published a guest post by Scott Young, who just spent about three months in China, attempting to stay immersed in Chinese the whole time (even while traveling with his non-Chinese friend, Vat). I didn’t comment on my own interactions with Scott, though, or my thoughts on his experiment. So I’ll do that now.

Here’s a video we took in the (then) empty office next to the AllSet Learning office. We were plagued by technical problems, but Vat’s persistence got us through.

On “No English”

I was expecting that Scott would be taking a break from his “immersion” while talking to me and talk to me in English. We had exchanged emails before we met in person, and it was all in English. But no, from the get-go, Scott spoke nothing but Chinese to me. (And Vat too.) So we talked for quite a while (before and after the video), and it was all entirely in Chinese.

I part of me finds this weird. I suppose it’s because it violates the “efficiency” principle I talk about in my language power struggle post. We both knew that we could communicate absolutely effortlessly in English.

But he was a man on a mission, with a “no English” rule, and I totally respected that. In fact, It’s becoming less and less weird for me to think of Chinese as an international language. Chinese is the language of our office, and I speak to our (non-Chinese) interns mostly in Chinese as well (as long as they’re not absolute beginners).

On Studying before You Arrive

Scott mentions that he had studied Chinese for 105 hours before coming to China. Vat didn’t. I’m sure there are other factors at play, but there was a noticeable difference between Scott’s and Vat’s Chinese levels. I think Scott was also putting more time into Chinese in China (Vat also had video and architecture-related interests to pursue). But the head start undoubtedly helped Scott a lot.

This is a common thread I’ve seen in a lot of success stories, though: for China, in particular, prior study seems to help immensely. I’ve heard and discussed with friends theories about having to deal with the “triple threat” of (1) unfamiliar language, (2) tones, and (3) Chinese characters leading to higher levels of frustration when tackling Chinese. In fact, it’s a good reason to delay studying characters a bit, if it means less frustration and a stronger foundation in pinyin and pronunciation.

I had three semesters of Chinese before setting foot in China. I sure struggled when I got here, but I was essentially focusing entirely on listening and pronunciation for the first couple of months. I knew pinyin, had the grammar basics down, and knew all the characters I needed for a while. I know that focus helped me tremendously.

On Preventing Friendships

In the guest post, Scott states:

> What matters is that you are not speaking English to prevent: (1) Forming friendships with people who can’t or won’t speak Chinese….

This is key, but it seems quite harsh. Can you imagine bumping into Scott while traveling around China, trying to strike up a friendly conversation with him about areas in Yunnan he’d recommend visiting, and being totally blown off by him in Chinese? Would you be heartless enough to similarly rebuff a friendly fellow traveller? This is exactly what Scott is advocating, though: “prevent[ing] forming friendships with people who can’t or won’t speak Chinese.”

I know that Scott is right, though. I also know people that have followed less extreme versions of this policy in order to make the most of their time in China, although those people tended to have more than just three months, so a few conversations here and there weren’t a huge deal. And then there’s the “expat bubble” crowd, of course. Most of those people didn’t intentionally form the bubble; it just “kind of happened.”

When I first started teaching at my first job in China at Zhejiang University City College (ZUCC), my only co-workers were four Australians. I fully expected those guys would be my new friends, and I was excited to finally get to know some Aussies. But they cruelly brushed me off; they were a tight-knit group, and not at all interested in letting me in. So I was on my own, lonely, and motivated to learn Chinese. I hung out with my Chinese roommate a lot. I studied. I went out and practiced with random people. I made more Chinese friends. I learned Chinese. I was kind of lucky, really.

This is one of those personality things, though. I’d be curious to hear from readers who have tried this, whether successful or not, and what the results were.

24

Jun 2014Communication Is the Challenge

I have only vague memories of learning geometry in high school. I liked it because you got to draw stuff, and while some of my classmates hated doing proofs, I didn’t mind them so much. I saw them as sort of a puzzle, and the logic of the whole process appealed to me. I can’t say I ever really loved geometry or found it fun, however.

Fast forward to last weekend. I discovered “Euclid the Game” on Hacker News. It presents geometric challenges as a sort of game. It’s essentially the same as proofs, but rather than “prove this boring thing” it challenges you, and gives you a little toolbar with geometric “weapons” you can apply. One of the things that impressed me most is that after you demonstrate that you know how to construct a parallel or perpendicular line, or how to translate a line–with simpler tools–you gain new “shortcut buttons” for those tasks in your toolbar. Nice!

Anyway, the point of all this is that learning is a lot more fun when it’s presented as a fun challenge. How many of us had to learn geometry by memorizing axioms, and then theorems, and then drudging through joyless proofs? With this “Euclid the Game,” the challenge factor keeps you going, and the stuff you’re supposed to memorize you just kind of “pick up” because you need it to solve the challenges. And the cherry on top is that there’s more than one correct way to solve the challenges, because, hey, geometry is flexible like that.

Does any of this sound familiar? (Yes, I’m talking about language learning.)

If you treat a language as a big long list of words and grammar points, then yes, you can drudge through it just like any other horrible soul-sucking schoolwork. But in language, the real challenge should always be communication with another human being. If your language learning method doesn’t involve this crucial feature, it’s time to start questioning your methods.

Maybe geometry isn’t your thing at all, and unlike me, you could never get into “Euclid the Game.” But everyone enjoys communicating. Put down the flashcards and take up the challenge.

19

Jun 2014Scott Young on Short-term Chinese Immersion

This is a guest post by blogger Scott Young. He got in touch with me before we met in China, and I was impressed by his “All Chinese All the Time” enthusiasm. In this post he shares some advice on how to create an immersion experience if you’re only in China for a short time and really serious about learning Chinese. (Oh, also the video his friend Vat made is pretty cool, too.)

In China and can’t access Vimeo? See the mini-documentary on YouKu

I think most people would agree immersion is the best way to learn a language. Unfortunately, that can often be difficult to pull off, even if you live in the country with the language you’re trying to learn. Immersion in China can be even trickier, where both difficulties with the language and the culture can be difficult barriers to surmount.

After a three-month stay in China, I’m hardly an expert on learning Chinese. However I did go from a minimal amount of prior self-study (105 hours, exactly), to passing the HSK 4 and being able to hold fairly complex conversations in Chinese after my brief stay.

At the risk of sounding immodest, I believe immersion was the key to my progress and I believe it’s the biggest component most new learners in China lack which holds them back. In this article, I want to spell out exactly what steps I took to create a sustainable immersive environment to improve my Chinese over a short stay.

Immersion from the First Day

One of the most important factors is that I aimed for an immersive environment, from the first day in China. Given I was barely able to make up a sentence and couldn’t understand anything Chinese people were saying to me, that might sound too difficult to replicate.

However, I believe it is possible to create an immersive environment from the first day, even if you aren’t enrolled in one of those fancy boarding schools which force you to speak Chinese. Second, I believe this step is one of the most important you can take for your overall rate of improvement.

A Tale of Two Languages

Chinese isn’t my first foreign language I’ve learned. That was French.

I lived in France for a year during my senior year of university. Despite four years of grade school classes, my French was nonexistent. I had always wanted to learn a foreign language, so getting an opportunity to live abroad was the perfect time to do that.

Three months into my stay in France, with roughly the same advance preparation as I had for China, I wrote a French exam that all students were required to take. I scored a D. (Which according to the school roughly translated into an “A2” by the CEFR)

I’m still mostly the same person I was four years ago. Certainly any innate talent for learning languages, if such a thing exists, would have been the same then as it is now. My motivation for learning French was at least as strong as learning Chinese. So why did I fail to do what I have done in Chinese with an “easy” language like French?

I believe the difference was immersion.

Although I was living in France to learn French, most of my friends were other foreigners who spoke English. Even the French friends I had tended to speak in English with me because we were part of an English speaking group.

By the time I had realized my mistake, it had become very hard to change course. The only way I could start an immersive environment now would have been to cut off all my non-French speaking friends and force myself to speak in an unfamiliar language with people who were used to me speaking to them in English.

After this experience, I resolved to do things differently next time. So when I came to learn Chinese, I wanted to make sure I was building an immersive environment from Day 1.

How to Build an Immersive Environment with Limited Chinese

Immersion sounds great, but it’s definitely easier said than done. I believe that managing the development of your environment while living in China can be trickier than learning Chinese, and it’s very easy to get into some bad habits (or friendships) that will hold you back.

The most direct step I took was simply not speaking in English.

The no-English rule is not possible to perfectly implement (at least for mere mortals like myself). I had to speak in English when I arrived to the landlord. I had to use English in some brief moments to coordinate with possible tutors. I had to use English with Vat, my friend who I traveled with and shot the documentary you can see at the top of this article, as he hadn’t done the same amount of prior preparation as myself.

However, even an imperfect attempt at not speaking English can still be good enough for practical purposes. What matters is that you are not speaking English to prevent:

- Forming friendships with people who can’t or won’t speak Chinese.

- Beginning friendships with Chinese people who want to use you to practice their English.

- Using a bit of initial isolation to motivate yourself to learn Chinese and make Chinese friends.

This is an intense strategy, so you might be wondering whether it’s something you can successfully execute. I’ve done this now with Chinese, Spanish, Portuguese and I’m currently in the beginning phases of applying it with Korean. While it can be very intense, I want to stress that the intensity is mostly temporary.

Chinese may take a little longer to break in than a European language, but you will break through, and when you do, you’ll be in the immersive environment you need to make rapid improvements in your Chinese.

What happens if you fail? Don’t worry, pick yourself up and try again. The goal isn’t perfection, simply enough commitment to using Chinese that you get the three benefits I listed above.

Specific Strategies for Getting Over the Hump

Simply not speaking in English is rather vague, so I want to add some concrete examples of steps I found useful, both in China, and in other countries where I’ve applied this technique.

1. Make friends with your tutor and ask him or her to introduce you to new friends.

China can be a hard country to befriend strangers when your ability with the language is quite low. It wasn’t until the third month that I found myself starting to make friends randomly, as before my Chinese was too limited to have more than basic chit-chat.

My strategy in China was to actually get a couple tutors around the same age as myself (I ended up settling on two), who I could have lessons with. From the day I first met them, I mentioned that I was interested in meeting other Chinese people, so I tried to pick tutors who could introduce me to other Chinese speaking people.

That strategy is a bit slow, and it took me two weeks before I was getting introductions, but it ended up resulting in dozens of new friends, all in Chinese.

2. Get a home-base restaurant and talk to the staff.

This is a good one in China because restaurants are so cheap and numerous, but I’ve used it in all of the countries I applied this method, so I believe it is easily replicable.

Basically, find a place where you (a) like the food enough to eat there everyday and (b) the owner or staff is very friendly and chatty with you. Even if you can’t have great conversations with them yet, this can be a good first friendship in the language because you will see them often enough that there is no need for complex introductions or swapping of contact details.

3. Go to language meetups, once you’ve successfully had all-Chinese tutoring sessions.

I like language exchanges for making friends in the language. But these can be a trap in China, where everyone just practices English on the largely non-Chinese speaking foreign population.

The problem isn’t that Chinese people won’t speak in Chinese with you. Just the opposite, I’ve found most Chinese people like talking to foreigners, and are quite happy when they don’t have to use their English (even in language meetups). Most people I’ve met have been quite patient with me as I’ve stuttered out broken sentences.

The problem is that, if you haven’t successfully had a conversation with one of your tutors entirely in Chinese (or at least mostly in Chinese, where you weren’t constantly switching back to full English sentences), it is easy to get sucked into the English speaking groups.

Conclusions

You might have a job in China where you need to speak English, so fully avoiding the problems I mentioned are out of the question. However, the same steps can be applied privately to start surrounding yourself in a Chinese-speaking social circle, so that you can at least get the benefits of partial immersion.

Immersion is an intense strategy, but it’s also one you must design. Unfortunately, many first-timers believe it is guaranteed by living in the country and then lament at the difficulty of learning Chinese when they’ve made little progress despite years in China.

The intensity may be uncomfortable for the first month or two, but that’s a one-time cost. Once you reach an intermediate level of Chinese, continuing to improve by making new Chinese-speaking friends gets easier and easier. Averaged out over years, I believe immersion actually takes less effort than constant amount of Chinese study within an English-speaking bubble, it just happens to compress most of that effort in the first bit.

Scott Young is a blogger, traveler and author of Learn More, Study Less (recently published in Chinese). If you join his newsletter, you can get a free ebook detailing the strategy he uses to learn faster.

13

Jun 2014Hacking Chinese Resources

Olle at Hacking Chinese has just announced Hacking Chinese Resources, a new voting-style collection of useful tools for studying Chinese. Check it out.

The danger in a project like this is that it will be overrun by marketing agents with their own agendas, and that the content which rises to the top doesn’t actually represent the best of what’s out there. Olle looks like he’s making efforts to deal with that issue, so here’s hoping Hacking Chinese Resources does well.