24

Sep 2015Bill Bishop: Trust between Obama and Xi is a Fantasy

I enjoyed this little piece of political philosophizing from Bill Bishop’s Sinocism Newsletter, so I thought I’d share:

> I have a bit of headache wading through the mass of competing OpEds about the Xi visit and US-China relations. One thing I do not understand is people talking about the need for trust in the US-China relationship. I am sorry to be so cynical (then again the name of this newsletter rhymes with cynicism) but Chinese politicians do not trust each other, US politicians do not trust each other, the Communist Party has made it very clear it sees itself in an ideological struggle with the “Western values” represented by America, so how can any sentient person really expect there to be trust between the two governments?

> Or is it just a diplo-speak nicety people think needs to be parroted, even though everyone realizes it is a bit of a fantasy?

The last article I read on the topic called the two world leaders frenemies. (I’m pretty sure such a designation would preclude trust?)

P.S. Bill Bishop recently left China, but Sinocism lives on. Even when based in Washington, D.C., a better source for China reading is not likely to come along any time soon.

22

Sep 2015How I Learned Chinese (part 4)

It seems to have become a tradition of mine to drag this series out over years and years, but this part should be the last one I need to write for quite some time. Just a quick sum up:

- Part 1 (2007): How I got started in Chinese in college

- Part 2 (2007): How I coped with no one understanding me after arriving in China, and how I got to a decent (intermediate) level of Chinese

- Part 3 (2012): How I updated my goals to help me power through the “intermediate plateau”

This post is more of a look at how I learned, rather than specifically what I did. I’d also like to look more closely at the relationship between study and practice. This balance is essential to any learner’s long-term progress, but there’s no one-size-fits-all solution.

Learning Timeline

First, a quick timeline of my experiences:

- 1998-1999 (STUDY): Started Chinese classes at UF. “Practice” consisted of meeting a language partner once a week, but it barely made a difference.

- 2000 (PRACTICE): Arrived in China and started using my busted Chinese. Was dismayed to discover my Chinese was decidedly not awesome.

- 2001 (STUDY): Found a professional tutor who was able to help me fix my major pronunciation issues. This, in turn, led to much more efficient practice.

- 2001-2003 (PRACTICE): Lots of speaking practice with people around me (details here), some self-study on the side, but the major emphasis was practice.

- 2003 (STUDY): One-semester HSK course helped me identify some holes in my self-studied Chinese, especially in more formal Chinese.

- 2004 (PRACTICE): My first job in Shanghai was English-related, but I still got to use Chinese for most of my work. I learned a lot.

- 2004-2005 (STUDY): Prepped for grad school, using a tutor.

- 2005-2007 (STUDY/PRACTICE): Masters program in applied linguistics in Chinese. Heavy components of both practice (everything was in Chinese) and study (there was plenty of vocabulary and sophisticated grammar to learn).

- 2006-2013 (PRACTICE): Working at ChinesePod was tons of great practice, but I also learned a great deal, even if I was never directly “studying.”

- 2010-present (PRACTICE): Building AllSet Learning, learning to run a business, managing Chinese employees, was all done in Chinese. More great practice. And learning all day long.

The Role of Study

Especially in the beginning, you need a helping hand to learn Chinese. It’s very hard to start “practicing” without some kind of structured study. Many learners turn to schools for this, and tutors are another option (both have pros and cons), but it’s hard to argue that some kind of formal study is not helpful for most people.

The key is that study alone will rarely lead to real fluency. At some point (preferably in the elementary stages), you need to be given ample opportunities to speak Chinese in a natural way. Hopefully this is motivating and fun, and not something scary. If the end goal is spoken fluency, you have to start practicing speaking. Exorcise those demons of bad Chinese!

Study itself has many forms, however, and I’ve found that many learners appreciate school lessons in the early stages, whereas 1-on-1 tutoring becomes much more useful once there’s a good foundation, and concrete goals for how Chinese can be applied start to take shape. So for me, the “schooling” was OK as my first three semesters’ foundation and then as HSK prep. Tutoring helped me fix the very specific pronunciation problems I was still having when I first arrived in China (I really needed individualized attention for that). Later, again, tutoring made the most sense once I had the concrete goal of getting into grad school and needed help learning some specific material. (I also had to spend a lot of time managing my tutor, though… There was no AllSet Learning back then!)

I remember very clearly, sitting in my Chinese syntax class in grad school, listening to the professor detail some finer points on the relationships between certain Chinese prepositions and verbs, and thinking, “these are the ultimate advanced Chinese lessons. The meta-lessons that even native speakers are clueless on.” So there was always a strong aspect of “study” within the “practice” of grad school in Chinese. Once I started working, though, “practice” really became the main focus, and “study” was relegated to an ongoing “as needed” self-directed activity.

The Role of Practice

My real “practice” started when I arrived in China. It was the reality check I needed, but also a source of motivation. To quote part 2:

OK, so I already knew when I arrived that my pronunciation wasn’t great. I knew I got tones wrong sometimes. I knew I had been fudging Mandarin’s “x” and “q” consonants for two years. But I wasn’t prepared for the end result: people frequently just plain didn’t understand me. At all.

At first I tried to downplay it with “that guy was just not used to talking to foreigners” or “it must be my Beijing-centric pronunciation.” That attitude didn’t really help me. I got through the denial stage pretty quickly and ended up with a firm conviction: the problem is me. I then gathered all my resolve and launched into a relentless campaign of self-criticism.

That was kind of rough. It would have been nice if I had been prepared for actual communication in Chinese in progressive stages. I got through the initial shock, though.

The early years of practice in China were both the hardest and the most fun. They were the hardest for me because I had to force myself to talk to strangers regularly, and often my non-comprehension made those conversations quite awkward. Oh yes, I dealt with a lot of awkwardness. But my psyche was protected, in part, by this weird “I can’t believe I’m in China talking to people in Chinese” euphoria that imparted a certain delusion of unreality. And so in many ways, it all felt like a weird, fun dream.

The “delusion of unreality” slowly wears off as you get to the Intermediate stage, however. Most things Chinese people say in Chinese are no longer “funny” or “crazy” because you’re used to Chinese culture, and you’re used to the way people speak. To give a simple example, you stop thinking, “it’s so weird that Chinese people are always asking me if I’ve eaten” every time and you start thinking of it as a normal greeting. You stop “hearing Chinese” and you start just listening to people. And just talking back.

It’s at this point that the practical application type of “practice” becomes really important. For me, it was my initial training job in Shanghai first. Then it was the work of my Chinese language masters program: following the lectures, completing the readings, writing papers, etc. Then it was directing ChinesePod lesson development. And then it was my work at AllSet Learning (and later Mandarin Companion).

It’s all about a Mix

If you look at my timeline, you’ll see a lot of vacillating between “study” and “practice.” You’ll see long periods of “practice” broken up by mostly shorter periods of intense “study.” And you’ll notice that the “study” is heavily concentrated in the beginning, whereas “practice” is heavily concentrated in the later stages.

Hopefully you never have a total lack of practice in the beginning (even if it’s just with a teacher), but practice should really ramp up over time until it’s just “application” (using Chinese for normal communication or work or whatever). Similarly, your “study” looms large in the beginning, but should never go away completely (even advanced learners pick up new vocabulary all the time), as it shrinks down in overall prominence.

It’s not that I concocted this; it’s not a method. It’s a very natural process, and I’m merely reflecting on how these principles played out in my own experience. Through my work at AllSet Learning, I often help frustrated learners, and a study/practice imbalance is one of the major sources of frustration. Some learners have unrealistic expectations about how far traditional “study” can take them, fluency-wise. Others have been immersed in “practice” for far too long and are not even sure how to go about addressing the gaps caused by years of neglecting “study.” I admit that it’s partly just luck, but somehow I managed to strike the right balance over the years.

I can’t say I learned Chinese the fastest or to some mind-blowing level, but I achieved my goals and have the skills to apply it in my career. I’ll never stop studying Chinese (“活到老学到老,” as the Chinese say), but especially due to the strong “practice” components of the past 10 years, I do feel confident in saying “I’ve learned Chinese.” (Just not all of it!)

10

Sep 2015Update on Work at AllSet

I don’t blog as often as I once did, mostly because I’m so busy at work. (Also, having two kids now doesn’t give me lots of extra free time.) Sometimes I get asked about what AllSet Learning is doing. I’ve even been criticized for not writing about it enough here!

So here’s a little Q&A to fill in readers…

Q: Is AllSet Learning still providing 1-on-1 Chinese lessons in Shanghai?

Yes, of course! We normally do not advertise; we rely mainly on word of mouth (which has been quite kind to us over the years). We’ve got lots of satisfied customers at all levels, each studying a personalized curriculum. If you’re in Shanghai, definitely get in touch. (If you’re not in Shanghai, it might be worth getting in touch too.)

Q: But you’re also doing other things?

Yes, working day in and day out with individual learners helps me stay in touch with learners’ needs and keeps me sensitive to where the gaps still are. Then we release products to fill those gaps when we have time to develop them. So we’ve got the Chinese Grammar Wiki, Chinese Pronunciation Wiki, iOS Pinyin chart and Picture Book Reader, and Pronunciation Packs, plus the books we developed for Mandarin Companion.

Q: And you still have time for new clients?

Yes, in fact, we’re currently gearing up to start new clients post-summer, so if you’ve been deliberating, now is a good time, while there’s still room. Summer is typically our low season, so we spend more time on product development, then get busier again with client duties in the fall.

Q: So were you developing anything new this summer?

Definitely! We’ve had a very busy summer. Aside from the new Mandarin Companion Level 2 book, we’ve got quite a few things almost done, which we’re currently polishing and will be announcing soon. (If you’re curious about these, sign up for the newsletter to the latest news.)

Q: Aren’t you also involved in the Outlier Chinese Dictionary workbook?

Yes indeed! I’ve already started meeting and discussing with Ash, and that project will start soon as well. I’m very excited about this, because it’s something I’ve sensed a need for among my clients. Unlike some language issues, characters are not something I want to tackle on my own, so it’s very satisfying to be part of a larger effort at helping making characters more accessible to learners.

That’s about it for now! If you’re curious about anything AllSet Learning is doing, please get in touch.

04

Sep 2015Can Chinese Names and English Names Co-exist?

I recent saw this question on Quora and liked the following answer by Raj Bhuptani:

Do Americans prefer that Chinese people use their original Chinese name or an English name?

I think either name is fine, but personally something that annoys me is when a Chinese person gives his Chinese name to his Chinese friends and his English name to his non-Chinese friends. The reason for using an English name should be that you prefer the English name, not that you think your Chinese name is too hard for an American to pronounce. In addition to feeling a bit patronizing (“My name is Mingyuan, but you can call me William”), using different names with different friends can lead to confusion when you have both Chinese and non-Chinese friends (in college, more than once have I had an epiphany along the lines of “Ohhhh! Lucy and Lu Xi are the same person?!”)

I totally agree with this answer, but I also understand that Chinese people with a name like “Xu Juan” or the like basically have no hope of Americans pronouncing their name correctly, so it’s kind of a dilemma.

I personally arrived in China eager to use a Chinese name (I chose 潘吉), but over the years started to feel it was a little silly, and just reverted to my English name. In my case, “John” is quite easy for Chinese speakers, and now, pretty much only my in-laws call me by my Chinese name (which is fine).

It’s safe to say, though, that most Chinese names are harder for English speakers than most English names are for Chinese speakers.

Solution: The world needs to learn Chinese! (ha… OK, maybe just pinyin?)

01

Sep 2015McDonalds Getting its Pun on

I spotted a punny McDonalds ad in the subway yesterday that might not be obvious to a lot of learners:

The ad presupposes knowledge of the word 充电宝, which is a pretty recent word, and isn’t in a lot of dictionaries yet. 充电 means “to recharge” (electricity, but sometimes metaphorically as well). 宝 means “treasure” and is also used in the common word for “baby” (宝宝), but here it just means “thing.” 充电器 already means “charger” (for electronics), but the difference here is that a 充电宝 is a battery that can be carried with you and used to recharge you smartphone. These portable chargers seem to be way more popular in China than the battery-extending cases (Mophie and the like) I’ve seen a number of Americans use.

OK, so back to the pun. It’s focused on the “bǎo” part of 充电宝 (portable charger). It uses the character 饱, meaning “full”. It creates the sense that a meal at McDonalds is a “recharging fill” (not “full recharge”).

Anyway, you get the idea.

26

Aug 2015More Effort Means More Learning

This answer seems obvious to me, but I’m still asked this question often enough that it’s worth a public answer.

Q: What do you think about just downloading an HSK vocabulary deck for my flashcard app and learning vocabulary that way?

A: That’s a pretty terrible way to learn Chinese, even if you can accept that it’s just mindless vocabulary acquisition and not really “learning Chinese.”

Q: What? Why?

A: I’m glad you asked…

- Unless you’re studying for the test, the HSK vocabulary list is not the vocabulary you need. It’s an arbitrary list full of vocabulary you don’t need. Sure, there’s some useful vocabulary in there, but how much useless vocabulary do you not mind memorizing?

- Downloading a free, ready-made list of vocabulary is the worst way to study new words. It’s because it’s instant and effortless. To your brain, that makes it devoid of value. Your brain doesn’t like to retain information it deems devoid of value. The nice thing about studying something devoid of value, though, is that it’s so very easy and painless to give up on.

- Curating your own list of useful vocabulary, taken from real-life situations or texts you actually want to read is a much better way to learn new words. You made the effort to go out and find that vocabulary, and the vocabulary itself is a means to an end: having a real conversation or reading a passage you’re interested in.

- You know what’s better than curating your own list of vocabulary in your flashcard program? Actually getting some cards, and writing the words you want to learn on those flat dead-tree rectangles, all caveman-style. Put pen to paper and actually physically create your implements of vocabulary review. That’s effort, and your brain respects that.

Requiring personal effort makes the learning process memorable, and as a result, what you learn sticks better.

But hey, go ahead and download the free HSK vocab list. It won’t hurt anything; it’s easy to delete a week later. Your brain won’t mind at all.

18

Aug 2015Upgrading Self-Introductions

Remember when you first started studying Chinese? The teacher always made you introduce yourself. It usually consisted of something like the following:

- My name is _________.

- I am from _________.

- I am _________ years old.

It’s all very cute and practical, and instinctively seems appropriate to both beginners in a language as well as three-year-old native speakers. This type of basic self-introduction is generally accepted as normal and necessary.

Unfortunately, this self-introduction (自我介绍 in Chinese) often goes un-updated for years on end. So you’ve been studying Chinese for 2 years, are at a solid intermediate level, and yet you basically still recite the same self-introduction above (perhaps swapping out your age for your job). That’s kinda lame.

In reality, every new word you learn, every cool new grammar point, could potentially enhance your stale old self-introduction. Take the time to do the upgrade! Just like failing to upgrade your 听不懂 is going to affect your interactions with Chinese people, failing to upgrade your self-introduction will have the same effect. Ideally, your self-introduction should be as cutting-edge, language-wise, as you can smoothly handle. It’s OK to show off your Chinese level with your self-introduction just a little, if it means people will stop treating you like you just learned to say 你好.

The nice thing about self-introductions is that you can be creative. Keeping in mind that this is going to vary a lot depending on the individual, the audience, and the Chinese level of the speaker, here are a few suggestions to get you going:

- If you have a Chinese name, and you tell your audience which characters are used to write it, use creative, interesting choices of words that use the characters in your name. You can use this trick to associate your name with a famous Chinese person you’re a fan of, or whatever you can come up with.

- As you tell your audience where you are from, use the opportunity to stifle annoying stereotypes from the beginning (e.g. “I’m an American but I’ve never owned a gun,” or “I’m French but I’m not at all romantic,” etc.).

- Add in your Chinese zodiac sign instead of your age for fun (and to show that you’re not a total newb in this whole “Chinese culture” game).

- Depending on the audience, you may want to head off other annoying questions, by saying things like “I can use chopsticks” or “I am used to eating Chinese food”, but make sure that it comes across as a joke, and not the lamest brag ever.

- Include a few details about why you first came to China or why you haven’t left yet, after all these years (because the Chinese are already curious about that kind of thing)… but be prepared for follow-up questions!

- Include what Chinese movies, books, or dishes you like for a chance to make an instant connection with certain members of your audience.

P.S. Here are two cute kids’ self-introduction videos on Flickr: [1], [2].

12

Aug 2015“True Detective” in Chinese is Sneaky

I just finished Season 2 of the bleak HBO TV series True Detective, and enjoyed it (although it depressed me a bit). I’ve had a few discussions with Chinese friends about the show, and I realized that the Chinese name of the show is worth a mention.

So the Chinese name of the show is 真探. The word for “detective” in Chinese is 侦探. Notice that both are pronounced exactly the same: “zhēn tàn.”

So if you’re hearing the name of this show in Chinese for the first time, you’d probably think it is just called “zhēntàn,” translating to “The Detective” in English. You have to actually see the characters to realize that a “True” has been slipped in there. (Makes me think of a line from the show intro: “I live among you… well disguised.”) It’s different from the common character swaps you see in Chinese brand names because it’s actually a translation, and it’s the fusing of two meaningful words into one.

And this got me thinking about similar wordplay for other names. It’s not a true portmanteau, as I understand the term, because there is no phonetic fusing going on. The “fusing” is entirely writing-based, but extends to meaning once you see it. We can do this in English too, I’m sure, but I can’t think of any examples right now.

I actually see this a lot going the other way (semantically) in Chinese: a name makes you think of certain meanings associated with certain characters (that you think you hear), but then the name purposely switches out those characters (in an attempt to be more “subtle”?). One example of that is 肯德基. (The Chinese name for Kentucky is 肯塔基州, but since it’s the name for KFC, the brand could have used 鸡 instead of 基). Another examples is 珍爱网, a dating site, which is clearly playing on the “true love” meaning of the word 真爱.

06

Aug 2015Monkey King: Hero Is Back and Cultural Gaps

I recently watched a Chinese movie called Monkey King: Hero Is Back in English, or 大圣归来 (Da Sheng Guilai) in Chinese (full name: 西游记之大圣归来). The name 大圣 is short for 齐天大圣, which is another name for 孙悟空, the “Monkey King” character from Journey to the West (西游记).

Have I lost you yet? This is actually a pretty good movie, with high-quality animation, but it’s written for a Chinese audience, and as such has a lot of cultural assumptions built in. Although I’m generally familiar with the story of Journey to the West (西游记), it’s a classic that every native-born Chinese person is intimately familiar with from childhood, so foreigners trying to understand the story are at a bit of a disadvantage. (I’m going to provide all the Chinese characters and pinyin for Chinese learners like I always do, but the following info should still help even if you’re not studying Chinese. Mouse over characters for pinyin.)

Pretty much every Chinese person, young and old, knows that Journey to the West has 4 main heroes (plus a horse). One annoying thing is that each character has multiple Chinese names and multiple English translations of those names. The names given in parentheses (in bold) are the ones I hear used the most by Chinese friends.

- 唐僧 (Tang Seng), AKA 唐三藏, 玄奘, or Tripitaka in English. He’s a Buddhist monk on a mission to retrieve the sacred sutra from the West. He’s the one that always wears the tall hat.

- 孙悟空 (Sun Wukong), AKA 齐天大圣, the Monkey King, also called just “Monkey” in some translations. He’s a badass rebel with an attitude that can do all sorts of magic, including taking on 72 different forms.

- 猪八戒 (Zhu Bajie), AKA “Pigsy.” Once an immortal, but now a greedy pig-man with magical powers, but only 36 forms.

- 沙悟净 (Sha Wujing), AKA Friar Sand or “Sandy.” Also a fallen immortal, he’s in the shape of a man, but he only knows 18 forms. He seems to be the lackey of the group, and is often seen hauling around everyone’s luggage. (Not nearly as famous or beloved as the above 3 characters.)

- 玉龙 AKA 白龙马 (“White Dragon Horse”), a white dragon and son of the Dragon King. Takes the form of Tang Seng’s steed as atonement for a crime. (Not nearly as famous or beloved as the top 3 characters.)

OK, now how do these traditional characters fit into the new movie 大圣归来 (Da Sheng Guilai)? That’s key to understanding it. I won’t give any real spoilers, but the following are a few important notes that all Chinese viewers understand immediately, which should clear a few things up for foreign viewers:

- The movie kicks off with Sun Wukong starting a brawl in heaven. He’s basically a troublemaker and is pissing everyone off. You get a taste of his full power here, and also see him change form.

- In the end of the opening heavenly brawl, Sun Wukong is stopped by 佛祖 (the Big Buddha), and imprisoned for 500 years under a mountain. This detail is faithful to the original.

- When Sun Wukong is first released from imprisonment, he is surprised to discover that he’s lost most of his powers, and it seems to be that magical shackle thing holding them back.

- Sun Wukong is referred to in the movie by three names/titles: 齐天大圣, 大圣, and 孙悟空.

- 唐僧, the main monk on a mission in Journey to the West, is the little boy named 江流儿 in the new movie. This name is made up for the new movie, and making him into a little boy has no basis in the original story; it’s a fresh twist. He is often referred to by Chinese audiences, for convenience, as 小唐僧 (Little Tang Seng). Everyone knows who he’s supposed to be.

- The old man that takes care of Little Tang Seng and raises him to be a monk is just created for convenience in this adaptation, as is the little girl that Little Tang Seng is protecting.

- Sun Wukong and Zhu Bajie are represented pretty faithfully to tradition in this movie.

- The “White Dragon Horse” makes a few appearances in this new movie, but he has not yet become Tang Seng’s steed. (That will probably happen in a sequel.)

- Sha Wujing does not make an appearance in this new movie. (That will also probably happen in a sequel.)

If you’re studying Chinese, I recommend you check out this movie. It’s pretty easy to follow even without the above information, but it’s nice to know how it “plugs into” contemporary Chinese culture.

I hope the forthcoming English-dubbed version is better than this:

Music video with scenes from the movie:

Additional Links:

– 西游记之大圣归来 on Baidu (Chinese)

– Monkey King: Hero Is Back on IMDb

– Monkey King: Hero Is Back on Wikipedia

– Journey to the West on Wikipedia

23

Jul 2015Watermelon Man’s Secret

I was tempted to use a title like, “You think this guy is just selling watermelons, but you won’t believe what he does next!”

Anyway, on my morning commute, I passed this dejected-looking vendor, eyes downcast, as he shirtlessly watched over his truckload of watermelons. He was staring at his scale, and I imagined he was thinking about how absurd it is that this electronic device determines his income.

As I got closer, I saw what he was actually doing.

Yeah, that’s an iPad. Watermelon guy was watching some kind of drama (but due to bad luck, the screen was black right when I snapped this shot).

21

Jul 2015A “Home” for Escher in Chinese Design

Here’s a poster I spotted in a mall recently:

The character there is 家, meaning “house,” “home,” or sometimes even “family.”

The first thing I noticed was its Escher-like quality, updated to a modern aesthetic. (Reminded me of Monument Valley even more than Escher directly, actually.) Very cool, and not something I see much in China, for sure!

The second thing I noticed was that the stylized character on the poster is missing a few strokes. If this character is 家, then the bottom part is supposed to be 豕, which has 7 strokes. Instead, the bottom part looks more like the 5-stroke 永, minus the top stroke.

I found this odd, because this is a pretty big difference, and in my experience the Chinese don’t take character mutilation too lightly, especially when it’s not just private use. My wife’s response was just to shrug it off, though, with a, “yeah, but it’s still supposed to be 家.”

What do your Chinese friends think? Cool design, or heinous affront to the sanctity of the 10 strokes of the Chinese character 家?

15

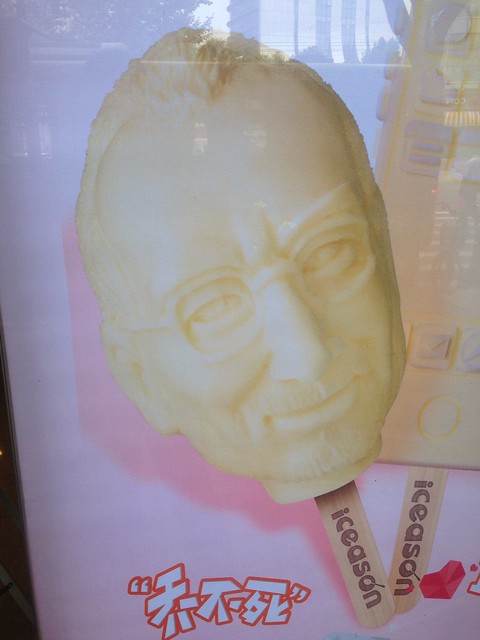

Jul 2015Steve Jobs Ice Cream in Shanghai

Passing by Chinese “Italian-style” ice cream shop “Iceason” with a friend yesterday, we were startled to see an ad featuring “3D printed” ice cream bars in the likeness of the late Steve Jobs:

The surname “Jobs” is normally written in Chinese as “乔布斯,” or “Qiaobusi” in pinyin (a transliteration, where the characters are chosen for phonetic value only, and essentially have no meaning). For this ice cream bar, it’s written as “乔不死,” also “Qiaobusi” in pinyin, but with different characters so that it includes the phrase “not die” (不死).

The same shop also sells “3D printed” ice cream bars in the shape of the Apple watch and iPhone.

08

Jul 2015Dian Dian Sha

This is the logo for a service called 点点啥 (Dian Dian Sha):

So this is the Chinese verb 点 (meaning “to order (food)”), reduplicated. The word 啥 is a colloquial way to say 什么 (“what”), used more in northern China.

Nice characterplay here, the second 点 replaced by the service bell, while the first 点 is modified a bit to look more like the bell.

One thing beginners might not know is that the character component consisting of four short diagonal lines (as in 点) is frequently written as a single horizontal line. You can actually see this in some PRC character simplifications:

- 魚 → 鱼

- 馬 → 马

Obviously, it’s not applied across the board, leaving us with characters like 点, 热, and 煮, which still use the four short diagonal lines in printed form. In handwritten forms (or certain fonts), even those four short lines frequently get turned into a horizontal line (usually kinda squiggly).

点点啥 (Dian Dian Sha) has an app aimed at reduced food-related wait times.

02

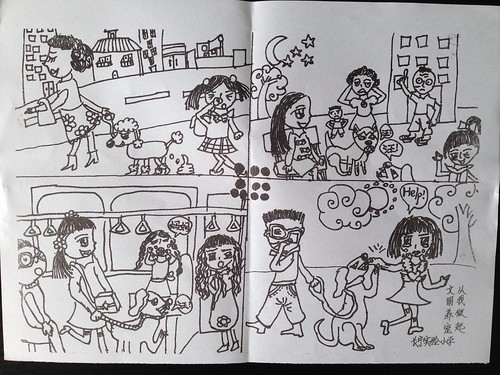

Jul 2015Elementary School Volunteers Push for a More Civilized Shanghai

I was impressed by the “propaganda” handed to me in the subway yesterday. I had seen lots of elementary schoolers on the streets engaged in some sort of volunteer work, and then in the subway I experienced it firsthand. Here’s the flyer I was given:

The “汪” represents the barking sound a dog makes in Chinese. (In panel 3, the little girls is saying “妈妈“, “mommy.”) The characters in the lower righthand corner read:

> 从我做起 [it starts with me]

> 文明养宠 [civilized care for pets]

> 长宁实验小学 [Changning Experimental Elementary School]

What impressed me was the idea that the school is (1) educating the kids to be “civilized” (文明), but also (2) trying to use the kids to influence the less civilized adults (who are arguably most in need of this type of education, but also prone to negatively influencing the kids). Made me think of the brilliant Thai anti-smoking ad that also used kids.

Here’s hoping these efforts pay off! We’d all like a “more civilized” Shanghai (with less dog poop).

30

Jun 2015Mike’s Immersion Experience in the Chinese Countryside

I’ve had many conversations with learners looking for an immersion experience in China. Well, Michael Hurwitz, my friend (and former AllSet Learning client) decided to round out his China experience with a month in the Sichuan countryside (outside Chengdu) doing farm work. He went through an organization called WWOOF that sets up labor-hungry foreigners with organic farms and the like.

But is a month enough? Was it a good experience? I interviewed Mike to get his take on it.

Could you explain why you felt the need to run off to the Chinese countryside for an immersion experience?

Mike: It was something I’d wanted to do for awhile, but the language element was only part of it. I was also interested in checking out a more “authentic” Chinese place than Shanghai, if that makes any sense. The lack of westerners and English speakers around was a big part of my reasoning, but I was also hoping that the stronger “Chineseness” of the 农村 [countryside] (and 农民 [rural workers], for that matter) would rub off on me a bit and that I’d understand a bit more about China, having seen a lifestyle very different than the urban one I’d been participating in.

What was the farm work like?

Mike: The work itself was nothing crazy, primarily because the farm was as much about environmental education as it was about growing stuff. I mostly planted trees and pulled weeds, with lots of other work thrown in. The farm’s owner was really flexible; for instance I sometimes have knee problems (because I’m secretly a 45-year old man) and he had no problem with me forgoing work that involved lots of crouching. Towards the end of my time there, the owner even had me translate some instruction manuals for products he’d ordered from the US into Chinese! Productive work, but not quite what I’d imagined beforehand.

How was the food?

Mike: Food was very hit or miss. I don’t eat pork, which complicated things, as one of the 阿姨s [ayis] simply couldn’t understand that, and often left me no meat alternatives, which is tough when you’re doing physical labor all day. However, the other 阿姨 [ayi] was a wizard in the kitchen and made some absolutely magnificent dishes that I still crave.

Were you able to practice a lot of Chinese? What kinds of conversations did you have? Was the location a good choice?

Mike: Definitely got a huge amount of practice. No one else on the farm spoke English, so all communication was done in Chinese. It was very productive in that it was easy to get past the normal sorts of introductory conversations and actually start talking with people about normal things grown-ups talk about.

This was very cool because so often as a foreigner you’re seen as more of a curiosity than an actual person, so you can’t really have genuine conversations, but living on the farm with the same people for an extended period helped me get past that.

The location was something of a mixed bag. While being out west meant there weren’t any English speakers, it also meant there were some very non-standard accents and a lot of older folks who just couldn’t speak Mandarin. It led to situations where I had to have younger people translate from the local dialect into Mandarin for me, which was colorful but inconvenient.

Another element was that many of the things I was doing and experiencing – farm work, new foods, new activities, etc – were things I had never had cause to talk about or learn the vocabulary for in Chinese, so there was a lot of learning on the fly there as well. It was a bit overwhelming at first but after a week or so it got a lot easier. It helped as well that the farm’s owner and his wife were Beijingers, so I could always lean on them when I needed something more 标准 [standard].

Would you recommend what you did to other learners looking for an immersion experience?

Mike: I would definitely recommend an immersion experience, but location-wise, I’d say I had mixed results. Being in a place with so many non-standard accents and weird dialects made it a less smooth experience than I’d hoped. I think volunteering somewhere with more standard Mandarin would ameliorate that though.

Would you recommend what you did as a purely cultural experience?

Mike: Most definitely. I didn’t know what to expect going into this experience but I learned a tremendous amount about farming and rural Chinese life. Most of the people I met were great and it was wonderful to see a totally different side of the Chinese experience!

25

Jun 2015Carefully Translate

I love how this translation is technically correct (and perfect English, mind you)… outside of context:

As usual, context is key for a correct translation.

This sentence is ambiguous because of the word 地. Is it 地 (de, neutral tone), the structural particle that turns words into adverbs? Or is it 地 (dì, fourth tone), meaning “ground”?

If it’s the former, you get, “carefully slide.” If it’s the latter, you get, “be careful; the ground is slippery.” Computers, those infamously stupid translators, still have a hard time with context.

18

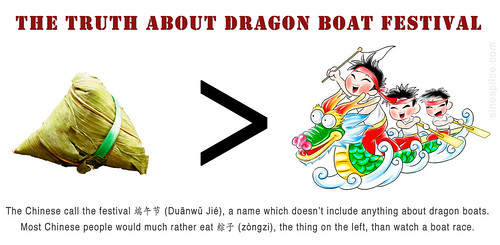

Jun 2015Dragon Boat Festival: who needs the boats?

One thing that many non-Chinese may not realize is that the average Chinese person doesn’t really care about dragon boat races on Dragon Boat Festival. Sure, we call it “Dragon Boat Festival” in English, but the dragon boats (龙舟) are just the easiest part of the festival’s traditions to translate. In fact, Wikipedia uses the name Duanwu Festival for its English article, reflecting the Chinese name 端午节.

The most visible tradition of Duanwu Festival for me personally has always been the zongzi (粽子), those bamboo-leaf-wrapped, stuffed glutinous rice triangle-ish things. They’re quite tasty (although you might want to be careful if you have an aversion to pork fat; some of them are a little high on fat and low on meat).

One of the traditions I just recently became aware of is the Duanwu Festival use of a plant called 艾草 (Artemisia argyi in English). It’s a strongly aromatic plant, and the idea is that you hang it by the doorway of your home to ward off bugs and disease.

Apparently this tradition is not observed by young people very much (at least in Shanghai), so I’m not sure how long this particular tradition will be around. But today I snapped some pictures of (mostly old) people loading up on 艾草 at the wet market in preparation for Duanwu Festival. (Those bundles are two for 5 RMB, which to me seems to reinforce the idea that only old people buy it.) Photos below.

Here’s what a zongzi gift set looks like:

This one, sold by a Korean bakery chain that pretends to be French (巴黎贝甜), includes 12 zongzi and retails for 158 RMB. (Normally individual zongzi sell for less than 10 RMB.)

In 2015 端午节 falls on June 20.

11

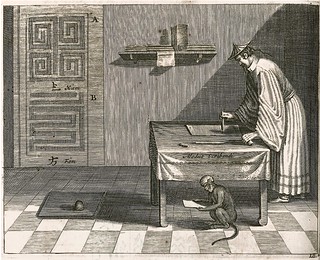

Jun 2015The Chinese Chinese Room

I’ve been listening to a series of lectures called Philosophy of Mind: Brains, Consciousness, and Thinking Machines. A lot of these concepts I’ve read about before, but it’s nice to have everything together in a coherent set. One of the topics covered refers to the Chinese Room, an anti-AI argument devised by philosopher John Searle:

> Searle writes in his first description of the argument: “Suppose that I’m locked in a room and … that I know no Chinese, either written or spoken”. He further supposes that he has a set of rules in English that “enable me to correlate one set of formal symbols with another set of formal symbols”, that is, the Chinese characters. These rules allow him to respond, in written Chinese, to questions, also written in Chinese, in such a way that the posers of the questions – who do understand Chinese – are convinced that Searle can actually understand the Chinese conversation too, even though he cannot. Similarly, he argues that if there is a computer program that allows a computer to carry on an intelligent conversation in a written language, the computer executing the program would not understand the conversation either.

> The experiment is the centerpiece of Searle’s Chinese room argument which holds that a program cannot give a computer a “mind”, “understanding” or “consciousness”, regardless of how intelligently it may make it behave. The argument is directed against the philosophical positions of functionalism and computationalism, which hold that the mind may be viewed as an information processing system operating on formal symbols.

So my first thought was: what do the Chinese call the Chinese room? The laowai room? Turns out the answer is a little more boring than that: in Chinese it’s called the 中文房间. (You might have been tempted to translate it as the 中国房间, but that doesn’t work as well, since the whole part of the argument is that there are these inscrutable symbols that can be manipulated. It’s Chinese characters that are key, not Chinese culture or nationality.)

The room is “Chinese,” of course, because of the inscrutable nature of Chinese characters. It boosts the argument if it feels like there’s no chance that the person in the room will actually learn them in the process of their Chinese room work.

I have to take umbrage at that: you can read Chinese. (If you want to.) I admit, though, that the Chinese room is not the best way to go about it.

There’s one other thought experiment mentioned which touches on China: the China brain. That one doesn’t seem to have a well-known translation (and no page on Wikipedia), but it seems at least some translators have gone with the straightforward 中国脑子. (This one refers to the people of China, and not the Chinese language itself.)

09

Jun 2015An Interview with Outlier Ash

I’m very happy to report that the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters I wrote about before has met its $75k funding goal. That means that this dictionary will soon be available through Pleco, so if you were holding out, doubtful it would actually happen, doubt no longer. Congratulations to the Outlier Linguistic Solutions team!

This is an interview with Ash Henson, Outlier Linguistic Solutions’ main academic guy. Like some other people I’ve spoken with, I was a bit apprehensive about the project at first, feeling it was all way too academic and probably not a good resource for beginners. The more I talked with Ash, though, the more I was convinced this was not the case. I do believe this is going to be a great resource for learners at all levels, and I look forward to using it myself, both for my own purposes, and for my beginner-level clients.

Anyway, here are some additional questions I had about the dictionary, answered by Ash.

1. You have an article on the problem with the concept of “radicals.” Would it be fair to say that radicals are just an outdated concept which we don’t need anymore because we can look almost everything up by computer now? Is your dictionary going to include the concept of radicals at all?

Well, I’d say that radicals are only reliable as a tool to look up characters in traditional dictionaries. If you only use electronic or software dictionaries, then it’s safe to say that you can ignore them. We will actually point out the radical for each character though, so that you can look up the radical for that character if you need to look it up in a paper dictionary. The main issue with “radicals” is that there are really several unique concepts that are called “radicals”. For instance, you often hear people say “Characters are made of radicals.” While that is a reasonable conclusion to make from the name “radical”, it misrepresents how characters actually work. There are around 500 semantic components that appear in characters and a lot of them cannot be broken down into “radicals”.

2. You’ve mentioned before that the Outlier Character Dictionary will include the most up-to-date research, including even corrections of mistakes in the legendary 说文解字 (Shuowen Jiezi). Could you give a simple example or two of that?

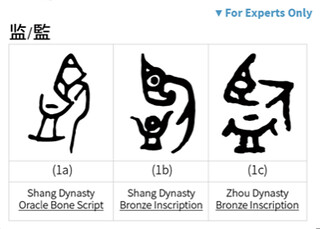

This type of data can be found in the Expert Edition. I’ll share two examples from the demo. For 監 (jiān) “to inspect”, the 說文 says that it is composed of the semantic component 臥 (wò) “to rest” which is used to express the idea “to look down from above” and the sound component 䘓 (kàn) “thick animal blood” abridged to 血. The problem is, 監 is a character from the early Shang dynasty (roughly 1600 bce to 1046 bce), while 臥 and 䘓 don’t appear until Warring States (roughly 475 bce to 221 bce).

Obviously, either this interpretation is anachronistic or maybe 臥 and 䘓 did exist earlier and we just haven’t found any proof. However, if you look at the earliest extant forms of 監, it’s very obvious that it’s a picture of a person looking into a container that has liquid in it. This “picture” is used to represent the idea “to inspect, examine” as this was how the ancients inspected their own faces, i.e., they used water in a container as a mirror.

Another example is 黑 hēi “black”. The 說文 says that the top part is a window and the bottom part is flame (炎 yán) and gives the meaning of 黑 as “the color of something burnt”. Note that the 說文 is explaining the Small Seal script form. The earliest forms show a person with a tattooed face. This is one of the ancient Five Punishments, where the name of the crime a person committed was tattooed onto their face.

3. After all this time, how can researchers be certain about what are mistakes in the 说文解字 (Shuowen Jiezi)?

Basically by way of tracing characters back to their earliest extant forms and seeing how characters are used in earlier scripts. Like in the 監 (jiān) example above, the 說文 says that it’s composed of 卧 and an abbreviated 䘓, but 卧 and 䘓 show up around a thousand years after 監. It’s like explaining the 1066 war in terms of the soldiers’ cell phones. Keep in mind, the author of the 說文 was a very erudite scholar, with a very broad range of knowledge, but he was limited by the information he had access to and by pre-scientific thinking. The 說文 is best understood as an insight into how Han dynasty Confucian scholars looked at the Small Seal script. Even with its problems, it still plays a very important role in this type of research.

4. You’ve told me before that a proper understanding of characters can help a learner guess the correct pronunciation of a character. This is hard to imagine, since a lot of components have a wide range of possible functions and even multiple possible pronunciations. (Examples: 干、赶、汗、旱 or 今、含、零、领、邻) How can you solve this mess?

Sound components can be really frustrating, because they generally don’t give an exact sound. In the same way semantic components give a hint as to the range of meaning a character might have, sound components generally also just give a range of sounds. English speakers might not realize this, but English spelling is very similar. That’s why the exact same spelling “minute” can be pronounced MIN-it for “60 seconds” or mahy-NOOT for “extremely small”. Actually, this second one can also be pronounced mahy-NYOOT, mi-NOOT or mi-NYOOT. As you can see, the spelling “minute” does not give an exact pronunciation, but a range of possible pronunciations.

As a native-English speaker, this isn’t a huge problem, because for the most part, we go from words we already know how to say correctly, to learning how to write them. During college we learn a lot of new, specialized words for the field of work we are training for. Most of these are learned either from reading or from hearing professors or other students use them. When I was in college, I often heard people say words incorrectly because they had only seen them in writing. This is a reflection of the fact that English spelling only gives a range of possible pronunciation rather than an exact, IPA-like pronunciation.

Making sense of sound patterns in Chinese characters is very useful, because they can be used to remember how to write characters. For instance, before I learned how sound works, whenever I had to write a character containing 艮 or 良, I would always ask myself, “Oh, man. Do I put that dot here or not?” It was very frustrating. Once I learned how sound components work, I looked up the pronunciation for 艮 (gèn) and 良 (liáng). Then I noticed that for characters pronounced “gen”, “hen”, or “ken”, it was 艮. If it was pronounced “lang”, “liang”, “nang” or “niang”, then it was 良. So, by learning about sound relations, I went from a meaningless dot-or-no-dot question, to a meaningful “What is the pronunciation of the character I want to write?” question. Though sound isn’t represented exactly in Chinese writing, there are a lot of clues we can use, especially if we know to look for them.

Now to the examples you brought up: 干、赶、汗、旱 or 今、含、零、领、邻

Let’s look at 干 (gān), 赶 (gǎn), 汗 (hàn), and 旱 (hàn) first. Notice that they all have the ending “-an” and that they all share the component 干. This is a strong clue that there is a sound relation. Also note that there is no discernible pattern with the tones. That’s because tones generally are not taken into account. Native speakers would generally use “-an” as the sound clue. However, it’s very useful to remember that “g-“, “k-” and “h-” are very closely related sounds.

As for 零 (líng), 领 (lǐng), and 邻 (lín). Notice that 令 is pronounced “lìng.” Once again, tones don’t count (not to say they aren’t important! They just aren’t represented by the sound component). Lastly, notice that the sound for 邻 ends in “-n” and not in “-ng.” In this particular case, that’s due to the simplification of 鄰 to 邻, and 粦 is pronounced “lín.”

Finally, looking at 今 (jīn) and 含 (hán), we notice that 今 and 令 above are graphically very similar, but like the 艮 (gèn) and 良 (liáng) example, we can use sound to keep 今 (jīn) and 令 (lìng) separate. Using sound patterns to understand the relation between 今 (jīn) and 含 (hán) is a little more complex. You have to understand both that “g-“, “k-” and “h-” are closely related as previously mentioned and that many “j-“, “q-“, and “x-” come from an earlier “g-“, “k-” and “h-“. In other words, two groups of closely related sounds are also somewhat related.

Why do sound series have this kind of variation? The answer to this question is fascinating, but complex. Most characters in use today find their origins thousands of years ago during the Zhou dynasty. Back then, the language was very different and very possibly had prefixes and suffixes and it was these prefixes and suffixes which cause this variation. Another reason is from regular sound changes over the last several thousand years.

5. Your dictionary is designed to provide a wealth of modern character research into characters through a modern interface. How would this be used by a beginner who sees characters as an annoying hurdle?

The key to optimal learning is obtaining the ability to use the system of Chinese characters as a tool for being able to recall character forms after long periods of time and as a tool for making intelligent guesses about characters you haven’t learned yet. Native speakers have these abilities, but they are far from perfect and they are the results of years of input. Non-native speakers learning Chinese can also get them after learning a few thousand characters.

However, as you can imagine, their instincts about characters are probably not as good as a native speaker’s. The main advantage of using our methods is that you can gain these abilities after a few hundred characters, because all of the sound and meaning connections are being pointed out explicitly for each character. And, as I showed above, if you learn our sound patterns, your feel for sound representation will be better than a native speaker’s. We also explain meaning connections in a more precise way, so your feeling for meaning representation will also be more accurate.

To those who think of characters as a nuisance, if you learn them our way, you’ll learn in a way that is both more meaningful (and therefore you’ll likely find it more interesting) and more effective, so you’ll spend less time re-learning characters. We can’t remove the pain entirely, but we can minimize it!

As of today, the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters Kickstarter is sill going.

04

Jun 2015Baymax is “Big White”

It doesn’t feel like the movie Big Hero 6 (called 超能陆战队 in mainland China) was hugely popular in Shanghai, but the character Baymax sure is! I see him everywhere these days. His Chinese name is 大白, literally, “big white.”

To me this name is cute, because it reminds me of 小白, a common name for a dog in China (kind of like “Fido” or “Spot”), except, well… bigger. When I ask Chinese friends, though, they don’t necessarily make the same connection.

The name 大白 also lends itself well to a little characterplay:

The eagle-eyed will also spot a little characterplay going on with the word 暖男, which is a relatively new slang term. Literally “warm male,” it refers to a sensitive, considerate guy. Chinese ads often go out of their way to incorporate the latest slang as much as possible.