16

Aug 2018Fukuoka 20 Years Later, post-China

I studied abroad in Japan for the 1997-98 academic year. During spring break, a friend and I hitchhiked from Osaka to Fukuoka. We visited from friends of mine, and explored the northern half of the island of Kyushu. Now, just over 20 years later, I’ve just visited Fukuoka again. This time the differences I noticed felt meaningful, and it’s not because of Japan. It’s because of me, and the 18 years I’ve spent in China in the meantime.

Obviously, this is a personal take. So-called “evidence” I cite is anecdotal. It doesn’t take into account the societies as a whole. I know, Fukuoka is not Tokyo. But if you can handle all that, read on.

The overwhelming sense I got which took hold of me early on in the visit and just wouldn’t let go is that Japan hasn’t changed much in 20 years. Of course it’s changed. But having lived in China, where pace of development permanently stuck in “breakneck speed,” Fukuoka really made me feel like Japan’s development is at a standstill. I’m no economist, but I’m into technology, so that’s one of the areas I was constantly checking up on. Remember when Japan felt super high-tech, back in the 80’s and 90’s? Now it feels kind of like Disney’s Epcot center, the “city of the future” conceived of in the 1970’s.

Just a few things that left an impression:

-

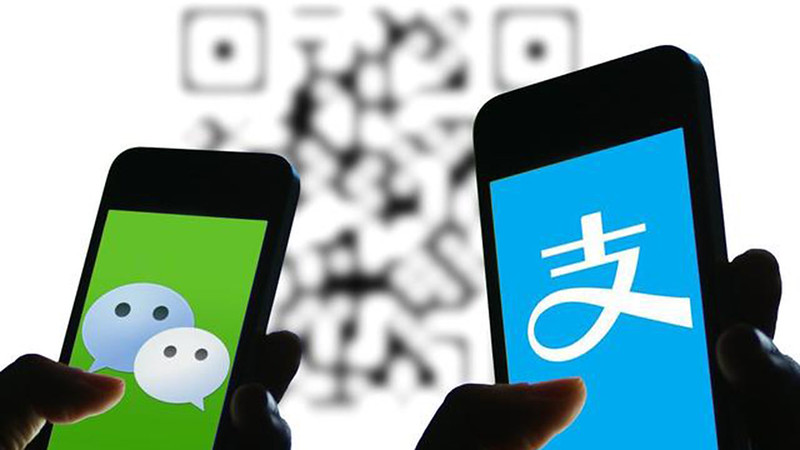

Vending machines everywhere. This is one of the things that’s so Japan, and I take no issue with the approach, except that these are literally the exact same machines from 20 years ago. They really haven’t changed. Meanwhile, China is outfitting these machines with scanners to support WeChat and AliPay.

-

“Cashless” restaurant ordering also means vending machines. My wife’s mind was blown that so many Japanese restaurants use meal ticket vending machines. This way the staff doesn’t have to handle money at all, and no one has to take orders. Makes sense, right? The modern Chinese solution, though, is to just put QR codes on the restaurant tables. Diners scan, order, and pay right away. The restaurant staff knows which table you ordered from. You barely have to talk to the staff, much less give them a ticket. No cash, no paper, no human interaction necessary. Cold efficiency.

-

Japan’s rail system is still legendary. Again, exactly the same as 20 years ago. You buy train tickets from vending machines. There’s a very real sense of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” and I can understand that. The train system works so well! It’s easy to use, and the trains all run on time. Shanghai’s subway and light rail system is not better than Fukuoka’s. And yet, there’s this feeling that in 10 more years (if that), Shanghai’s will be clearly superior, and Fukuoka’s will be the same.

-

Japan’s still doing great with recycling and environmental protection. I know, Japan still kills whales and does other bad things. But in general Japan is great at recycling, the streets are clean, and a retreat into the mountains (also clean and relatively unsullied) is never far away. I’m not sure if it’s possible, but it would be so great if China could catch up in this respect.

-

It’s not hard to be alone in Japan. Sure, the cities are super crowded, and apartments are small. But if you need to get away from it all, it feels way easier in Japan. You can hop on a train or bus, and a short ride later be headed into the mountains where you’ll be totally alone. Sure, it’s possible in China, but harder.

I could say a lot of these same things about China and the US, especially if I cherry-pick my cities. One interesting thing, though, was that when my wife told Japanese friends about how we use mobile payments for everything in Shanghai now, they were surprised and blown away. They had no idea.

10

Aug 2018Down Time in Japan

It’s been a busy summer so far, so it was nice to pop over to Fukuoka for a week to unwind a bit. I ended up doing a lot of thinking about Japan and China. More on that next week.

P.S. River crabs (河蟹) are totally real in Fukuoka and actually crawl all over the mountains!

26

Jul 2018The Torture of Japanese via Chinese

This week my wife and I have been planning a short family vacation to Japan. We’ll be hanging out in Fukuoka for a bit in August.

I majored in Japanese long ago, spoke pretty fluently, and was even reading Japanese literature. Now, after 18 years in China, my Japanese is rusty, but I do still speak it. Reading is much harder than it used to be, because all that Chinese in my brain wants to interpret the Japanese characters I see as Chinese. The more kana mixed in with the Japanese, the easier and more natural it is for me to read kanji as Japanese.

Anyway, what I’m finding much more difficult than reading Japanese is listening to it… in Chinese. The Chinese, of course, read Japanese kanji as if they were Chinese hanzi. In some cases, the Japanese words, pronounced as Chinese, become full-fledged loanwords in Chinese. No surprise, and no big deal. You get used to hearing Tokyo (東京) pronounced as “Dōngjīng,” and Kyoto (京都) as “Jīngdū,” etc.

But what you don’t get used to is hearing everything Japanese pronounced as Chinese. While we’re planning the trip, my wife is constantly dropping the Chinese names of all kinds of random Japanese places, and that’s something my poor brain can’t handle. On the one hand, they’re Japanese places, and I speak Japanese, so I want to know the Japanese names of the places we’re talking about. But on the other hand, my wife isn’t just going to learn Japanese for this trip, and she speaks to me mostly in Chinese, so of course she’s going to use the Chinese names. So my brain has to keep trying to jump through this series of hoops:

Chinese pronunciation → Chinese hanzi → Japanese kanji → Japanese name

(Sometimes I can get as far as step 2, but rarely can I get to step 4.)

Brain melting…

19

Jul 2018Updating Capsule Toy Vending Machines for Mobile Payments

You know those Japanese “capsule toy vending machines”? They’re called gashapon (ガシャポン) or gachapon (ガチャポン) in Japanese, and they’re fairly common all around Shanghai these days. The only problem is that these things were all originally designed to be coin-operated, and modern Chinese cities are using cash less and less, opting for mobile payment giants AliPay and WeChat whenever possible. So what’s a gachapon operator to do?

The most straightforward option is to offer token machines that accept mobile payments. The machine scans your mobile payment app’s QR code, you make the payment, and you get physical tokens. Then you use those in the machines to buy the capsule toys. Ka-chunk! Simple, effective, but it feels like it’s unnecessarily keeping physical currency as part of the operation.

Enter the mobile payment-powered gachapon network! I saw this in Shanghai’s Zhongshan Park Toys R Us:

So one of the machines has been converted into a payment unit with a camera for scanning QR codes. You make your payment there, then choose a machine and turn the crank to get the toy.

Works great! (My kids needed some mini Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles action figures. 20 RMB each… not cheap, but not outrageous.)

12

Jul 2018Time, Textbooks, and Podcasts

I’ve been in China 18 years now, and started working at ChinesePod over 10 years ago. I remember when we first started, we were creating lessons about simple everyday interactions which simply did not exist in any available textbook. The one that comes to mind is a Newbie lesson from 2006 called Using a Credit Card. The super useful question was:

现金还是刷卡? [Cash or credit?]

This lesson was so useful because credit cards had only fairly recently been introduced to China, or at least only in recent years become common. No textbooks taught 刷卡 (“to swipe a credit card”) because textbooks typically needed something like 10 years to catch up with development of that sort. So they weren’t even close, happy to focus on iterations of the classic “Going to the Post Office” chapter, which was rapidly becoming irrelevant in modern life.

In the years to follow, ChinesePod did lots of lessons involving 手机 (“cell phones”), and later 智能手机 (“smartphones”). I observed over time as textbooks struggled to update to even include the word 手机 at all.

The irony is that in 2018, even the lesson Using a Credit Card is now almost irrelevant itself. It’s so easy to bind your bank’s debit card to your WeChat or AliPay account, and Chinese consumers, for the most part, don’t like living on credit. So now the most important question you always hear when you buy something is:

支付宝还是微信? [AliPay or WeChat?]

It doesn’t appear that ChinesePod has this exact Newbie lesson yet, but it should. This new trend is especially important to point out to China newbies because in this particular regard, China is actually ahead of western countries, a fact which takes a lot of visitors by surprise.

I oversaw lesson production at ChinesePod for almost 8 years, and one thing became clear about the business model: the ChinesePod users wanted new lessons continually added. There were some in the company that considered this a problem, because the archive had already grown large enough to meet almost learner’s needs. Looking back from 2018, it’s easy to see that a lot of those lessons weren’t actually targeting serious communication problems for learners. On the other hand, some regular new content is also necessary in this age of rapid technological growth, where Chinese society develops quickly in new directions that no one can anticipate. Textbooks might find keeping up impossible on a traditional publishing cycle, but even for internet companies, it’s a challenge.

26

Jun 2018Eat Less Meat, says Huang Xuan

I spotted these pro-veggie ads in the Shanghai Metro recently:

少吃肉 [Eat less meat]

多走走 [Walk more]

少吃肉 [Eat less meat]

多福寿 [Be happier and live longer]

The obvious grammar points here are 少 + V and 多 + V (which don’t tend to come naturally to English speakers).

This is good to see, because as anyone who has lived in China should know, the (even remotely) affluent Chinese consume quite a bit of meat these days (and waste a lot of it, too).

The ads aren’t too clever, but the message is good, and there’s even a spot of characterplay in there. 蔬食 refers to a “vegetarian diet.”

The guy featured in the ad is 黄轩, an actor, and the ads are sponsored by WildAid.

Related links:

20

Jun 2018Graded Readers and the Wall of Characters

I did another podcast! In this one I talk with my partner at Mandarin Companion, Jared Turner, about the challenges of learning to read Chinese and how graded readers can help. The podcast (62 min.) is called: Chinese Graded Readers and ER in Chinese.

We covered a range of topics related to extensive reading (ER) and learning Chinese, and even did a bit of comparing learning Chinese and Japanese. On topice I think worth mentioning is something I last mentioned in 2012:

Most Chinese learners have a goal of one day being able to read a Chinese newspaper, or a novel in Chinese. And thanks to better and better tools for learning Chinese, it’s getting easier to work towards that goal progressively. However, even learners who have studied for quite a while report that they still struggle with the “wall of characters” mental block. It’s that irrational, overwhelming feeling (perhaps even a slight sense of panic) we sometimes get when confronted with a whole page of Chinese text: the dreaded “Wall of Characters.”

No doubt, this fear is partly culturally rooted. From childhood, many of us have considered Chinese characters as roughly equivalent with the concept “inscrutable.” At times our brains seem to revert to that primitive, ignorant state where that wall of characters really seems impenetrable.

Nowadays, the “wall of characters” is often online, rather than printed on paper. We have all kinds of tools to help us chip away at the wall. Relative beginners, with the right training, can quickly start blowing holes in that wall, and with a little time and patience, the wall does come crumbling down at the feet of the motivated learner, leaving nothing but glorious meaning in its place. That’s a beautiful thing.

One of the things I talked about in the podcast (at around 17:50) is how Chinese graded readers also help learners to tackle “the wall.” Maybe certain tools are “blowing holes” in the wall as mentioned above, but graded readers present much smaller, realistic walls as intermediate goals. They prepare the learner for the ultimate task: being able to confidently and reliably scale that wall on a regular basis.

No matter what language you’re learning, you should give graded readers a try. They help “build fluency now” and give learners a great sense of satisfaction that learners (and Chinese learners in particular) might otherwise be forced years to get a taste of. More on this is in the podcast.

14

Jun 2018Heads on a Plate in Kindergarten

My son’s preschool (in China, they still call it “kindergarten,” or 幼儿园) has a little case on display near the entrance to the school which shows what foods are on the menu for that day. The school uses small pieces of actual food for the display. It’s a great way to familiarize the little ones with various types of meat and vegetables, and I use it as a sort of English vocabulary review with my son, since he’s already learning the food vocabulary all in Chinese.

Well, despite having been in China for so long, I was a little shocked to see this last week:

…then this week, I saw this:

Some Chinese friends were a little surprised too, but at least no meat was wasted (unlike for the pork). I have to agree: it’s better that kids know from a young age where their meat comes from, rather than thinking meat just comes from a supermarket, and then being traumatized at the age of 10 to discover people are killing cute little animals just so they can eat them.

Still, I hope we don’t see a big pig head on a pike next week…

06

Jun 2018The Chinese Concept of “Dirty”

As a parent, I am keenly aware of all the work that goes into educating a child on what is “dirty” and how to avoid getting dirty, as well as why getting dirty is (normally) bad. The concept of “dirty” is surprisingly complex when you think about it, since some of it is visible and some not, and the “clean” and “dirty” objects can have all kinds of interactions. You really just have to be taught.

This issue reminds me of an experience I had years ago in Hangzhou. Quoting a blog post from 2005:

Shortly after I arrived in China, I went on a trip to a park with some Chinese friends. It had been a while since I had seen grass, so I was happy to sprawl out on it, which promptly resulted in my Chinese friends’ disapproval. “It’s dirty!” they told me. I just shook my head. In a corner of the world where there’s so little nature left to enjoy, they regard what little is left as “dirty”? That’s so sad! Then, as an afterthought, I ran my hand across the grass. My palm was turned gray. Dust. From the grass.

That little incident drove home that I really didn’t know how everything worked here, even when I was so sure I had it all figured out.

Just like children, as a China newbie, I, too, had to be educated on what was “dirty” in my new environment.

A similar example comes to mind: foreigners often think nothing of storing their bag on the ground next to their desks or chairs, but this frequently causes Chinese acquaintances to recoil in disgust. In China, you don’t put things you want to keep clean (like your bag) on the ground, even indoors. You also don’t put your bag on your bed at home. There are lots of “rules” to learn.

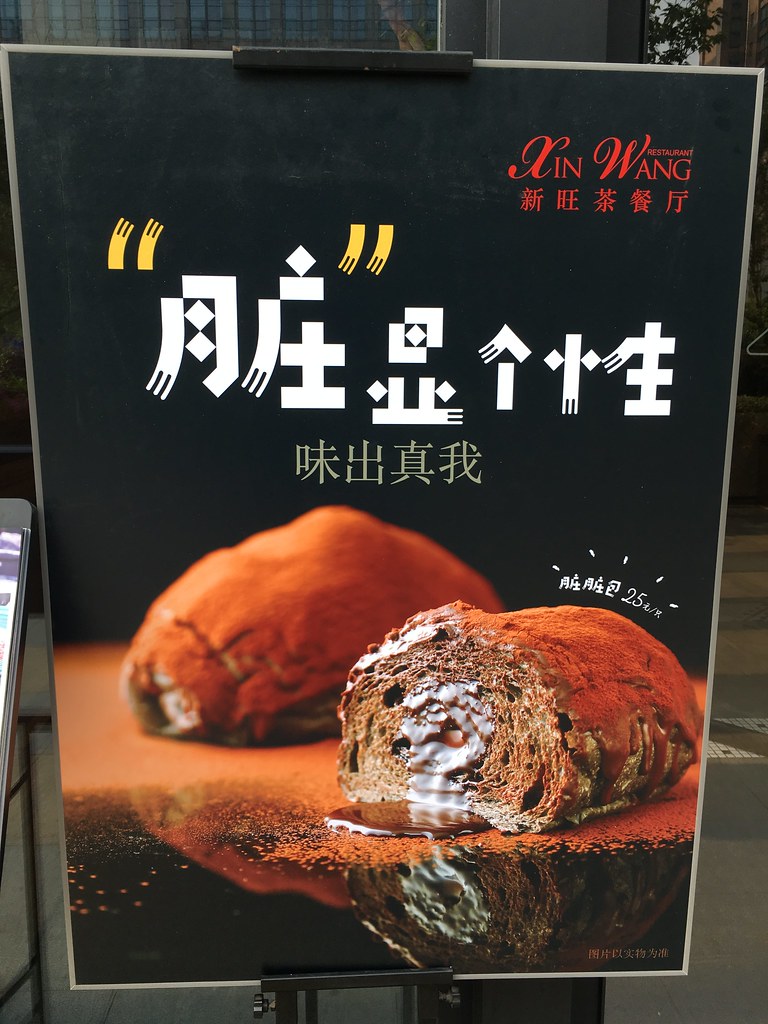

I was surprised, then, to see this ad:

“脏”显个性 [“Dirty” shows personality]

Of course we have “dirty desserts” in English as well, which is likely the source of this idea. But this concept feels even more eye-catching in China, where you’ve got to constantly be on your guard against the “dirt.”

29

May 2018Teachers Under Attack in Advertising?

I noticed these ads on the Shanghai Metro recently:

妈妈, [Mom,]

Tom老师

教我的发音 [The pronunciation Teacher Tom taught me]

Amy老师说不对! [Teacher Amy says is not correct]

妈妈, [Mom,]

今天外教 [today the foreign teacher]

把我的名字 [got my name]

叫错了三次。

“Dada English” is one of a new wave of Chinese online English learning platforms which includes “VIP KID.” What makes these platforms special is that they all purport to offer native speakers as teachers, and many of them are from North America or Europe. (I understand that some of the competition uses mostly teachers from the Philippines.) The first ad above emphasizes 欧美外教: teachers from North America and Europe.

What about the Chinese teacher of English? A resource long known to be often “less than perfect” with regard to native-like English abilities and yet nevertheless a crucial component of the educational system, is not even a part of the discussion these ads are trying to create. Rather, it’s a matter of where your foreign teacher is from and how professional he is.

I’m really curious if there is enough of the right kind of labor in North America and Europe to keep these business models afloat in the long-term. I suspect it’s going to be a lot harder building and maintaining a team of online freelance English teachers when those teachers are not Chinese or physically in China.

16

May 2018Chinese Perspectives on the Avengers: Infinity War

The Avengers: Infinity War finally hit theaters in China this past weekend. (You might say it was a hit.) Tired of carefully avoiding spoilers, I was among the first in China to see it. Since it’s come out, I’m enjoying the cultural impact and various manifestations of the Chinese perspective on the movie, from Avengers-themed WeChat stickers (with Chinese text) to hilarious Photoshop jobs.

Here’s one I enjoyed (mild spoilers, sort of?):

(I would credit the original source, but I can’t read the watermark.)

The Chinese reads:

- 超神: super-god

- 很厉害: very impressive

- 有帮上忙: were able to help

- 尽力了: really tried

- 废物: useless

- 一坨屎: pile of crap

Love the Chinese bluntness!

As for Thanos, what’s going to be the Chinese perspective on a “mad titan” that wants to take out half the population of the universe? That actually sounds quite familiar to citizens of a country with population issues of its own! So you get this:

That reads:

计划生育搞不好 紫薯你都吃不着

If you can’t get family planning right, no purple yams for you!

It’s a whole series; you can see more on Weibo here: @青红造了个白. (This same Photoshop artist has released good stuff before, like the Game of Thrones Chinese street vendors.)

09

May 2018Negative Questions Are the Hardest

There’s a certain type of question, phrased in the negative, which is answered entirely differently depending on the conventions of the language you’re speaking in. Take this English language exchange for example:

A: You’re not going?

B: No. (I’m not going.)

In English, we say no to the idea of going. Not going, therefore “no.”

Chinese works differently, however:

A: [You’re not going?] 你不去了?

B: [Yeah. (I’m not going.)] 嗯。(我不去了。)

In Chinese, we say yes to the statement itself. “Not going” is correct, therefore “yes.”

This is all fairly well-known stuff. Any English teacher in China is well aware of this issue, and hopefully anyone learning Chinese is as well. Even after you know about this difference, though, it takes some getting used to. You have to think about it for a while.

What I didn’t expect is that this seems to be just as hard for my bilingual kids. Both of my kids attend all-Chinese kindergarten, but I speak with them entirely in English at home. For the most part, they’re quite fluent in English for their ages, but occasionally Chinglish creeps in a little. How they respond to negative questions is another example of this: they respond the Chinese way.

So I’m constantly having conversations like this:

A: You’re not going?

B: Yeah.

A: You mean “no, I’m not going,” or “yes, I am going?”

B: No, I’m not going.

A: OK.

Not a big deal, but my 3-year-old is especially stubborn about answering these questions the Chinese way. He’ll get it eventually, though.

Still, if you’re feeling annoyed as a learner of Chinese that these are still tripping you up, you may take some consolation that even children, who supposedly “absorb language effortlessly like a sponge,” struggle with this. The big difference is that they don’t get discouraged, and they never ever give up.

03

May 2018Born Fried (shengjian)

Check out the English name of this little shop:

“Born Fried” is almost certainly an overly literal character-by-character translation of 生煎, a kind of bready, fried stuffed bun. Wikipedia describes it like this:

…a type of small, pan-fried baozi (steamed buns) which is a specialty of Shanghai. It is usually filled with pork and gelatin that melts into soup/liquid when cooked. Shengjian mantou has been one of the most common breakfast items in Shanghai since the early 1900s. As a ubiquitous breakfast item, it has a significant place in Shanghainese culture.

That same page gives the literal translation “raw-fried” for 生煎. Still, there’s something about “Born Fried”… it has a cool ring to it.

In case you’re not familiar with this little joyful celebration of grease, here are a few photos from Flickr (not my own; click through for the photographer’s photos):

25

Apr 2018Popular (blocky and backwards)

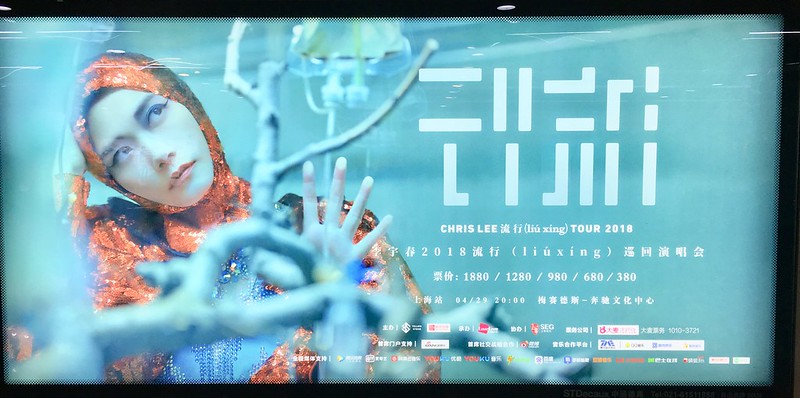

This ad (spotted in the Shanghai Metro) is interesting for a number of reasons:

What caught my attention was the font. “Blocky” (sometimes pixely) fonts are quite common, but I’ve never seen one so “spaced out” like this before. Yet the word 流行 (“popular”) is clearly visible.

And I didn’t even realize it at first, but the word 流行 is also written backwards! This is not something I have seen before, and I’m not sure what the intended effect is. (Maybe if I were a fan I’d get it?)

Nice of the poster to include the pinyin for 流行 (liúxíng), though!

Chris Lee is the English name for Li Yuchun (李宇春), which some of the older “China watcher” crowd might remember for her rise to prominence on the popular “Super Girl” singing competition in 2005.

19

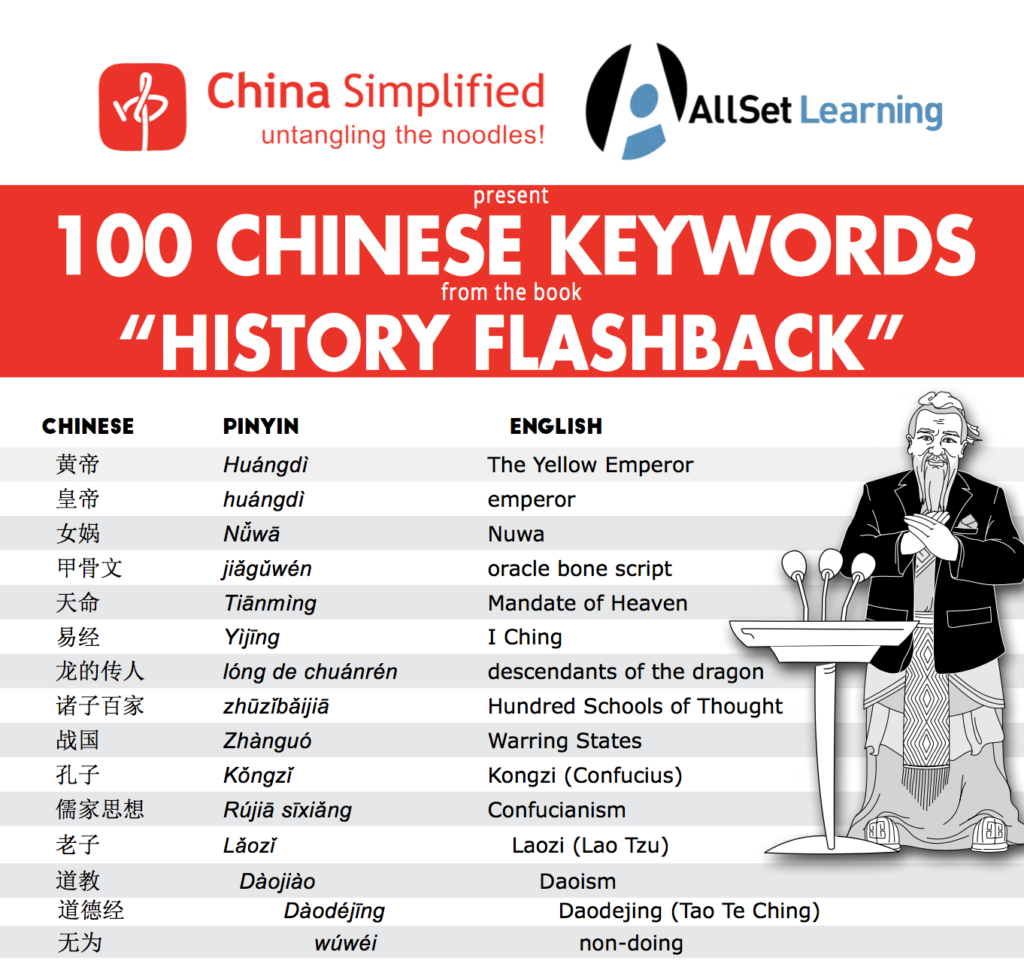

Apr 2018100 Chinese History Keywords

I’m not a history buff. I recognize it’s important to study history, and that no educated person should be ignorant of history. So while I do read about Chinese history, I don’t do it a lot. But every time I do pick up a Chinese history book, one of the things that drives me crazy about books on this topic is that so often there are no Chinese characters given for important names. (Or characters are given, but no pinyin.) Is this so hard?

China Simplified has a new book out called History Flashback. It’s a fun read, beautifully illustrated, and it’s actually pretty short! How does one condense “5000 years” of Chinese history into only 200 pages? Well, it’s possible. And although the book does a pretty good job of providing characters and pinyin for the Chinese names and other words mentioned, it seemed like a good starting point for a list of “essential Chinese history terms.”

So using this book as a starting point, my company AllSet Learning teamed up with China Simplified to create this handy list of 100 Chinese History Keywords. It’s a free PDF; no signup needed. Just download.

It was hard narrowing the original candidate list of 500 or so to only 100, but I think we did OK. What do you think? Are there any glaring omissions that an intermediate learner would really want?

Apr. 26 Update: We had a repeat word in the original list. It’s been removed, and we’re still at 100!

17

Apr 2018Dining Characterplay and “My Type”

After you’re done admiring the map, check out the character 菜 at the bottom:

(Sidenote! I have to wonder: why didn’t they choose to use chopsticks instead of a fork?)

菜 can mean “a dish (at a meal),” or “vegetables,” or even just “food,” depending on context. Here, the text reads:

全世界

都是你的菜

The ad uses a common idiom. 是我的菜 means “is to my liking” or, oddly enough, “is my cup of tea.”

Interesting enough, it’s super common to use this expression with relation to romantic attraction:

- 你是我的菜 (You’re my type)

- 你不是我的菜 (You’re not my type)

(In fact, both of the phrases above are the names of songs in Chinese!)

This is a great expression to learn early on because it’s fun, instantly comprehensible, easy to use, and uses only basic words and characters.

11

Apr 2018Tomb Sweeping: A Fading Tradition?

China had its Tomb Sweeping Day (清明节) last week, and that meant a three-day national holiday from Thursday, April 5 to Saturday, April 7 this year. (And then we were all supposed to work on Sunday to “make up for” one of those days off.)

The Chinese name for “Tomb Sweeping Day,” 清明节, is a little opaque. Both the characters 清 and 明 are pretty easy, but what do they mean together? “Pure Bright Festival?” Huh? And what does that have to do with sweeping a tomb?

Well, 清明 is “the name of the 5th solar term of the traditional East Asian lunisolar calendar,” according to Wikipedia. (Sorry, that wasn’t super interesting.)

I’m more interested in the tomb sweeping tradition. A day when the whole family, young and old, goes to visits the grave sites of their ancestors. What a great time to tell stories about these people, and to ensure that this aspect of Chinese culture stays alive and well.

The thing is, in Shanghai at least, I don’t see or hear about much activity surrounding actually visiting the graves of family members to 扫墓 (sweep the tombs), or at least not on 清明节 itself. What gives? Do people simply not care anymore?

I’ve spoken with a number of friends and family members on this topic, and this is what I’m hearing:

- I used to go with my family when I was young, but now that I’m grown up in working in Shanghai (far away from my hometown), I don’t go anymore.

- My mother goes for the whole family and sweeps the tombs.

- My mother goes for the whole family, but not on the holiday; there’s too much traffic on the roads. She goes a week in advance.

- In Beijing the locals all go.

Here are a few Chinese posts online, showing that there is some uncertainty out there among the younger people:

- 有没有人和我一样 从来不去扫墓的 (is anyone else the same as me, and never goes tomb sweeping)

- 每年都去扫墓,就是孝顺了吗? (is going tomb sweeping every year filial piety?

- 我该不该跟爸爸一起去扫墓烧香? (should I go with my dad to tomb sweep and burn incense?

Probably one of the most significant events that impacted how this holiday is observed was its being suppressed in the past as “superstition” or overly traditional and backward. It’s only been officially recognized by the government again since 2008, so the holiday has needed time to make a comeback. At the same time, when people live across the country from where their ancestors are buried, it’s not realistic to visit a far-off tomb over a 3-day holiday.

I think one thing that put this holiday in perspective for me was thinking about how Americans observe Memorial Day. Sure, some people make a point of honoring the fallen soldiers, but a lot of people just enjoy a day off and have a barbecue. I like to think that the Chinese take Tomb Sweeping Day a little more seriously, though. It’s about family, after all.

For those of you in China, did you notice many of your young-ish friends making a point to go tomb sweeping this year?

27

Mar 2018City Nightlife Characterplay

While perhaps not the cleverest characterplay, I like this treatment of the character 城, which means “city” (as in 城市), or sometimes “wall” (as in 长城). The phrase 不夜城 (literally, “not night city”) is similar to “the city that never sleeps.”

The text is:

龍之梦购物公园

新食代

不夜城

千人自助餐盛宴

Note: The way that “Cloud Nine Mall” (龍之梦) is written breaks the “golden rule” that I learned in Chinese 101: Either write entirely in simplified characters or write entirely in traditional characters. Never mix the two. The simplified dragon character 龙 is written using the traditional 龍. “食代” is a pun on 时代.

13

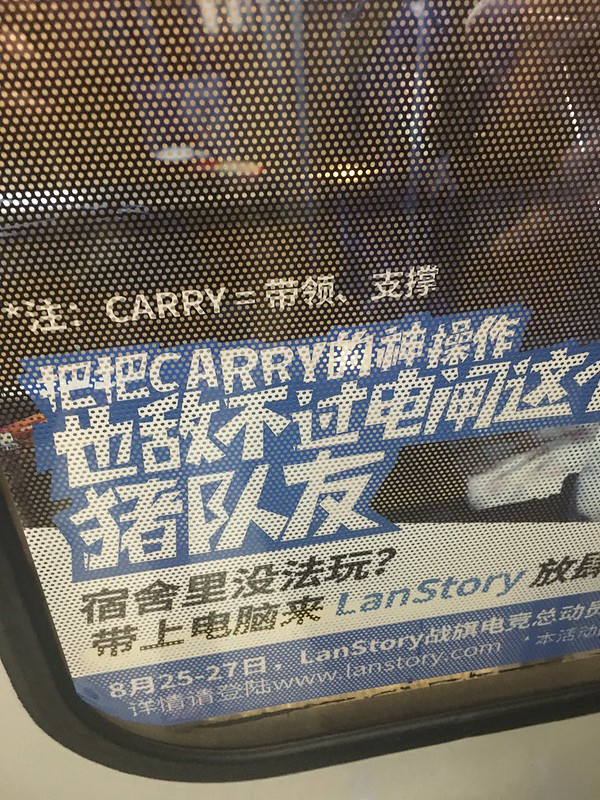

Mar 2018Not so clever use of “carry”

Saw this ad on the Shanghai Metro:

The top line of the text is a definition of the English word “carry,” used in the ad copy below:

*注:CARRY = 带领、支撑

Here’s a tip: if you need to define the foreign word, there’s a good chance it doesn’t belong in your ad.

07

Mar 2018Compassionately Featuring the Unseen in Advertising

Children with Down syndrome (唐氏综合征) are rarely seen in China, but it’s becoming more common. Still, I was surprised to see this ad in the Shanghai subway last year:

关爱“喜憨儿”

传递温暖,发现自己

The ad is spreading the idea that those with Down syndrome can still do some kinds of work and deserve our consideration.

The word 喜憨儿 is not a common one. It apparently comes from Taiwan, and is used to affectionately refer to people affected with Down syndrome, while hinting at the condition.

This year I spotted this other billboard in the subway:

关注流动人口健康

人人参与共建共享

The ad is advocating paying attention to migrant workers’ health.

流动人口 refers to the “migrant worker population” in big Chinese cities like Shanghai. Their jobs are hard, their pay is low, they have little job security and few benefits (if any), and on top of that, they’re discriminated against. The Chinese word more often used to refer to these people is 农民工. In Florida we have “migrant workers” (usually Mexican), but in the Chinese case, these workers are actual Chinese citizens.