31

May 2019Graded Readers at 150 Characters

This is just a quick note that Mandarin Companion has released its “Breakthrough Level,” a series of graded readers requiring only 150 simple characters to read.

I’ve been developing this for over a year, and it was quite a challenge. In fact, I originally designed Mandarin Companion’s Level 1 to be 300 characters because I felt at the time that that many characters really were needed to tell a full, decent story (10,000 characters long).

So has my opinion changed? Not exactly… Mandarin Companion Level 1 and 2 stories are all adaptations of existing classic works. Although we do take some liberties with the plots as we adapt them to Chinese stories, the overall plots remain intact. In order to adapt an existing story, you need a “story toolkit” of a certain size to pull it off.

Breakthrough Level (150 characters), on the other hand, doesn’t work that way. The stories are not adaptations. They’re original stories (by Jared and me), because they have to be. The plot of each story revolves around the words that we can actually work with at this level, and at 150 characters, we have just enough to pull it off. It’s been an interesting ride!

22

May 2019“X” and “SH” are not the same, Pam!

I enjoyed this:

“Meme artist” unknown, but I found the meme on the Chinese Language subreddit.

Obligatory educator nag: the “x” and “sh” sounds in pinyin are not the same sound, even if they may sound that way to you at first. Here are a few places you can go if you’re experiencing this confusion:

15

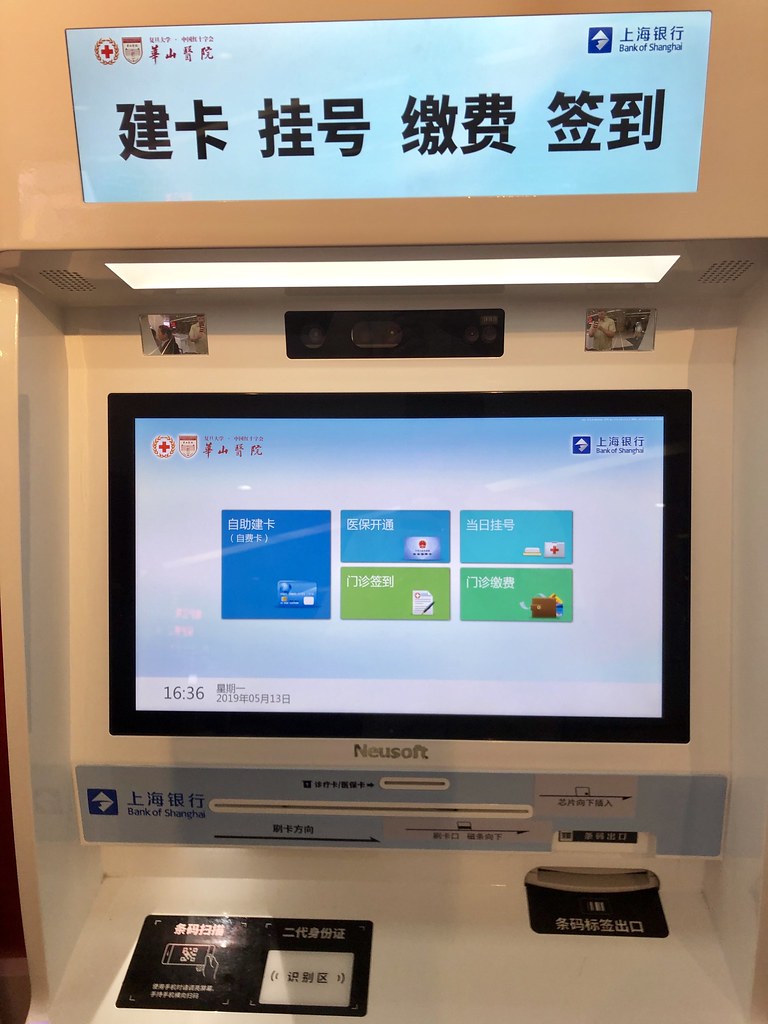

May 2019Are Chinese Hospitals Going Smart?

The average person in China doesn’t go to a doctor’s office when they get hurt or sick; they go straight to a hospital. Then they have a pretty horrible (often all-day) ordeal ahead of them, involving paying to get a number, waiting to be seen, getting briefly looked at to determine next steps, then waiting in line to pay for tests or other services, then waiting on the results, then taking them back to the original doctor for a final diagnosis, etc. It really is a ton of time waiting in line to be seen by a person with (understandably) very little patience, only to be curtly passed off to the next term of waiting.

So when recently I visited Huashan Hospital in Shanghai (one of the better public ones), I was surprised to see these kiosks:

The big title on the wall is 智慧e疗. The 智慧 refers to “smart,” and the e疗 is a pun on 医疗, which means “medical treatment.” (Not even healthcare is above a good old “e” pun!)

The closer view displays the following words:

- 建卡 (jiàn kǎ) to create a card (and associated account)

- 挂号 (guàhào) to register (at a hospital)

- 缴费 (jiǎofèi) to pay fees

- 签到 (qiāndào) to sign in (for an appointment)

I didn’t use this kiosk, and it seems not many people did. Hopefully progress is just around the corner!

08

May 2019Don’t Waste Time Studying What You Can Simply Acquire

One of my clients recently shared this article and asked my thoughts: Learning Chinese: from gruesome, to good, to great.

I’d sum up the three main pieces of advice for getting Chinese to “great” as follows:

- The first is changing where you talk from, physically. (Don’t sound all high-pitched.)

- The second is changing how you breathe. (Focus on tones.)

- The third is changing the rhythm. (Mimic native speakers.)

Although the titles sound like incredibly difficult tasks to accomplish, the practical advice which follows (and I’ve summed up in parentheses above) is not at all bad.

Learn Implicitly When You Can

The daunting tasks above touch on one of the tricky things about the field of second language acquisition: separating what should be explicitly taught from what should be learned implicitly through exposure and practice. For the vast majority of learners, all three of the main points (voice, breathing, rhythm) should be acquired implicitly over time, and don’t need much active focus. (Almost all learners benefit much more from focusing on the main pronunciation issues they’re probably already aware of, and getting a good handle on those.)

Everyone is different, though, so it’s possible that some people in certain circumstances (such as actors, professional singers, etc.) will benefit from active focus on breathing techniques, for example.

“Voice Quality”

I can give one example of my own personal experience with the one about “changing where you talk from, physically.” When I was working on my masters at East China Normal University (华东师范大学), one of my professors, Mao Shizhen, was an expert in phonology, as well as a voice coach for news broadcasters and the like. This was back in 2006 or 2007, and he once told me that my Chinese was quite good, but that my voice quality (I think he used the word “音色”) didn’t feel like a native Chinese person’s, and that to sound truly native, I should work on that. I later learned that I had a host of other issues I still needed to focus on to sound more native (most of which I’ve written about on Sinosplice at one point or another), so I didn’t worry about the “voice quality” issue or focus on it at all. Over time, though, my “voice quality” started sounding more and more natural due to increased fluency and practice. My Chinese may not be perfect or sound exactly like a native speaker’s, but I regularly fool people into thinking I’m a native speaker on the phone, and that’s good enough for me.

Explicit Tone Learning

An even better example to highlight the “explicit/implicit” difference is the tones of Mandarin Chinese. Most of us start out pathetically oblivious, and we really appreciate explicit instruction explaining what tones are, why they’re important, how to make them, how to practice them, etc. We want to know, and we feel that the explanation helps us, even if deep down we know that you could master tones simply by mimicking native speakers, just like a baby does. Unlike babies, adult learners can actually benefit a lot from explicit instruction. (They still need plenty of practice, though.)

Here’s the thing with tones, though: you need to learn the 4 tones (plus a neutral tone) well. You need to learn the tone change rules well. Everyone benefits greatly from tone pair practice, so you should do that as well (and that one will take a bit longer to really master).

But after you’ve hit the big three, you can stop digging deeper into the tiny intricacies of tones. Are there other, more subtle tone changes going on? Yes. Are all fourth tones created exactly equal? Actually, no. But these are questions that you can delegate to your (under-appreciated, underestimated) unconscious brain.

Conclusion

If you continue to strive to sound like native speakers, imitating their speech patterns as well as you can, you will get closer and closer to native as time goes on, and that includes implicitly learning aspects of the language that you didn’t even know you were learning. Have you ever asked a native speaker a question about their language, only to realize that you know more than they do about this particular aspect of their language (grammar, etymology, tone changes, etc.)? That’s because they’ve implicitly mastered the language and don’t need to be conscious of those concepts to use it fluently.

In fact, some of my proudest language learning moments have been discovering that I had mastered something without even studying it. This has included usage of certain words or grammar points, as well as tiny nitpicky details of pronunciation. Everything is fair game. Because you probably started out learning everything explicitly, it becomes a habit, and you may think that you’ll always have to do it that way. I’m happy to say that this is not the case. The better your Chinese becomes, the more you can (and should) learn implicitly, through exposure and regular practice.

So remember: you need practice, you need input. Focus on comprehension and imitating native speakers. You’ll learn a whole lot more implicitly than you think.

30

Apr 2019Learning a Language Is Like Learning Jazz

I’m not going to plug every single podcast “You Can Learn Chinese Podcast” we do, but then not every podcast we do has Dr. David Moser! For this one, I took over the interviewing responsibilities and had a good chat with Dr. Moser in our Shanghai studio.

We touch on a few topics I’ve covered on Sinosplice in the past:

(The jazz analogy part is new.)

And if you haven’t read this article by Dr. Moser, you should!

23

Apr 2019Come on, drink it! (says the hippo)

I spotted this new bubble milk tea shop recently:

The name is 喝嘛, which is just the verb 喝 meaning “to drink,” combined with the particle 嘛, used to “express the self-evident.” This is a command, though. How does a command “express the self-evident?”

To a native speaker, the feeling of the two usages is connected, but here the word 嘛 adds the feeling of a somewhat whiny, “come on, do it….” In fact, that phrase “come on” (used when persuading) could be translated 来嘛.

So yeah, this product name is actually saying, “come on, drink our product. You know you want to! Come on…”

What’s the deal with the hippo? Well, “hippo” in Chinese is 河马 (literally, “river horse,” which is also the meaning of the Greek roots of the English word as well). So we’ve got a pun here.

10

Apr 2019Neiwai’s Clever Logo

There’s a Chinese women’s clothing brand called NEIWAI (内外), literally, “inside-outside,” and it has one of the cleverest examples of characterplay that I’ve seen in a while [image source]:

It might take a few seconds to get, but what you’re seeing is the character 内 on the left, slightly modified so that the character 外 on the right overlaps it on its left side.

Here’s an unstylized version of the overlap that’s going on in the logo:

So, at the risk of pointing out the obvious, you have “outside” both inside and outside “inside.” Meanwhile, “inside” is also both inside and outside “outside.”

04

Apr 2019Meituan Morning Meeting

This picture was taken from my office building (18th floor):

It’s a crew of delivery guys which have become an extremely common site in big Chinese cities. The yellow uniforms belong to 美团 (Meituan), while the chief competitor, 饿了么 (Ele.me) decks its delivery guys out in light blue.

I’m no expert, but I would assume they do these daily morning meetings as the only time these “co-workers” are even together in the same place. The rest of the day they’re on and off their scooters all over the city, speeding from restaurant, to home, to restaurant, to home….

02

Apr 2019This box is very afraid

I was struck by the use of the word 怕 on this package:

It reads:

怕摔

怕压

Literally, “afraid of being dropped” and “afraid of being crushed.” I’m more used to seeing 易碎 on boxes: literally “easily broken” or “fragile.” This struck me as interesting because neither the box nor its contents actually fears anything. It doesn’t feel like an anthropomorphic usage, so it’s got to be an abstraction of the human “fear” emotion.

When I thought about it some more and talked about it with some AllSet Learning teachers, I realized it’s not just a matter of the two kinds of fear “human fear” and “abstracted fear”; there’s actually a whole range of usage with this 怕:

- 怕冷 (pà lěng) to be sensitive to the cold (lit. “to be afraid of cold”)

- 怕热 (pà rè) to be sensitive to heat (lit. “to be afraid of heat”)

- 怕辣 (pà là) to be sensitive to spiciness (lit. “to fear spicy”)

- 怕生 (pà shēng) to be afraid of strangers (lit. “fear the unfamiliar”)

- 怕黑 (pà hēi) to be afraid of the dark

- 怕死 (pà sǐ) to be afraid of death

- 怕高 (pà gāo) to be afraid of heights

- 怕人 (pà rén) to be shy around people (usu. describing a child), to be afraid of people (usu. describing an animal)

- 怕水 (pà shuǐ) to be afraid of water (usu. because one cannot swim)

Are they just degrees of the same emotion? Or are they totally different usages? It can be difficult to separate shades of meaning, especially for native speakers. This is what the field of semantics deals with.

To me, learning how other languages construct words and phrases in both familiar and utterly unfamiliar ways is one of the major joys of learning a language.

27

Mar 2019Chloe Bennett in the Shanghai Metro

When I first saw these ads, I felt that this woman looked familiar, but I couldn’t place her, and the Chinese name 汪可盈 didn’t mean anything to me.

I also felt like she didn’t look 100% ethnically Chinese, despite the Chinese name (and lack of English name).

Turns out this is Chloe Bennett, the star of Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.

It’s kind of interesting how her English name in the U.S. shows no trace of Chinese heritage, but when she appears on ads in China, her English name is not used at all.

Turns out that “Wang” is her surname by birth (her father is Chinese), and she actually pursued a singing career in mainland China as a teenager, using the name 汪可盈.

According to Wikipedia:

While pursuing an acting career in Hollywood, she changed her name to “Chloe Bennet,” after having trouble booking gigs with her last name. According to Bennet, using her father’s first name, rather than his last name avoids difficulties being cast as an ethnic Asian American while respecting her father.

Furthermore, she has explained Hollywood’s racism this way:

“Oh, the first audition I went on after I changed my name [from Wang to Bennet], I got booked. So that’s a pretty clear little snippet of how Hollywood works.”

The ad, using super simple Chinese, reads:

找工作 [(when) looking for a job]

我要跟 [I want to]

老板谈 [talk with the boss]

13

Mar 2019Geese in the Mall

This ad is hanging in Shanghai’s “Cloud 9” (龙之梦) shopping mall:

First of all the repeating character is 鹅, which means “goose.” In the circular logo, you can see a little characterplay going on with the goose head.

Above that, you have “鹅,鹅,鹅” which, of course, reads “goose, goose, goose.” This is a famous first line of a classical Chinese poem. It’s famous because it’s so simple, so a lot of kids memorize it as one of their first (if not the first) classical poems committed to memory.

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

鹅 鹅 鹅,

曲 项 向 天 歌。

白 毛 浮 绿 水,

红 掌 拨 清 波。

And in English (source):

Goose, goose, goose,

You bend your neck towards the sky and sing.

Your white feathers float on the emerald water,

Your red feet push the clear waves.

The banner is an ad for a restaurant, 鹅夫人, or “Madame Goose.”

06

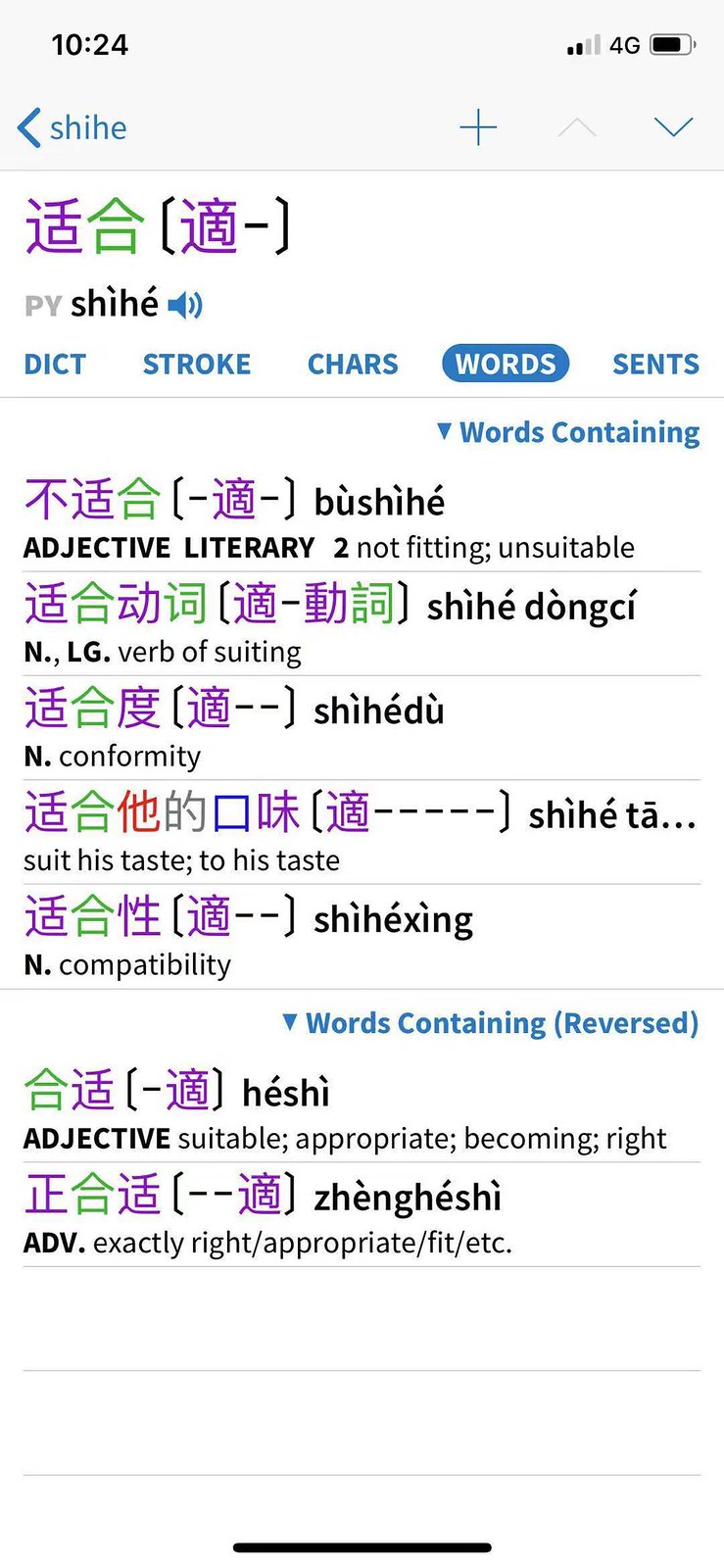

Mar 2019Pleco Tip: Word Containing (Reversed)

Pleco is a really powerful dictionary app, and it has a lot of features many people don’t even know about, such as the Clipboard Reader. This one is simply a part of dictionary entries that many people have never noticed.

Check out this entry, paying attention to the top and the bottom:

Note the bottom line: it’s an example of the word that was looked up, but in reverse.

More Examples

I’m not going to give too many (and I’ll explain why below), but here are some relatively common examples of what I’m talking about which intermediate learners may encounter:

- 适合 / 合适

- 互相 / 相互

- 犯罪 / 罪犯

- 代替 / 替代

(Mouse over the above words for pinyin.)

Why “Words Containing (Reverse)” Is Useful

This feature is really useful because we learners so often find ourselves misremembering new words by reversing the two characters in the new words that we learn (and most words in Mandarin are two characters). Many learners I’ve spoken with think that it’s a unique problem specific to them, but no, I can assure you: this happens to most, if not all, of us. It doesn’t mean you’re dyslexic or weird; it just means you’re normal.

The reason it’s important to identify words that are also another word in reverse is that it can prevent you from going crazy. This is because most often the reverse of a word you’ve learned is just plain wrong, but not always. Yes, I can remember several times when I’ve learned a word–let’s call it “AB”–and then I hear the word “BA” used in the same way. So then I think, “Oh, I misremembered it. It’s not ‘AB.’ It’s actually ‘BA’.” And then I once again hear “AB” used in the same way as “BA,” but there has enough time in between the two that my memory of what happened before is fuzzy. So then I think, “Oh, I misremembered it. It’s actually ‘AB’.” Rinse and repeat. That cycle of confusion can go on for a very long time.

How to Use It Correctly

So to protect your own sanity, it’s good to identify the words that are another word when you reverse the characters. (Sometimes they mean the same thing, and sometimes they totally don’t.)

Note that I’m not saying you should study a list of these words. That would just create more confusion, and a lot of the words won’t even be useful to you. It’s just good to learn that there is a “reverse word” for the words you already know or have just learned (and you can use Pleco to check that). If the “reverse word” is useful or common, that you might want to learn it. It’s it’s not, then it’s enough to just be vaguely aware that it exists (and you can always check Pleco again if your memory gets fuzzy).

The only problem with the Pleco feature is that if you look up a word in the dictionary, the “Dict” tabbed section is selected by default. You need to choose the “Words” section and also scroll to the bottom to find the “Words Containing (Reversed)” list.

26

Feb 2019Language Power Struggles, 9 Years Later

Probably my most popular blog post ever has been the Language Power Struggles one from way back in 2010. It’s hard to believe it’s been 9 years since I wrote that, and when I recently discussed the issue with Jared in our podcast, I realized that my attitudes have changed a bit over the years.

The advice that I gave in that article still stands: that in a battle of wills where communication is not the goal of interaction, no one really wins. And if you’re interacting with Chinese people both to improve your Chinese and to have meaningful communication with other human beings, it’s best not to participate in these silly “power struggles.”

And yet I can clearly remember routinely participating in these meaningless battles of will, whether at a restaurant talking to the server, or in a store, or getting a haircut… And now I recognize that back in the beginning a big part of what drove the stubbornness to engage in the struggles was insecurity. As if by refusing to communicate with me in Chinese, the other person was insulting the Chinese level I had worked so hard to achieve. I imagine the other person may often have felt the same way. So then you’re left with two egos duking it out over language supremacy, but also not really even caring about the other person’s level.

So nowadays I’m a lot more laid back and compassionate about people insisting on using English with me. Not everything has to be about principles of efficiency or showing proper “respect.” I know, it sure took me long enough to recognize this (and it’s a bit embarrassing), but I think that at the root of it was simply a dearth of quality communication in Chinese. After starting my own company in 2010 and working with all Chinese staff all day every day in Chinese, I no longer felt a need to use Chinese in every other interaction, because I had my fill.

So, to those of you who, like me, like to ponder these sociolinguistic issues, I ask you: do you participate in language power struggles? Do they annoy you? Is your emotional reaction to them (or lack thereof) a factor of your own personality, or do you think it’s related to “having your fill” practicing Chinese? How big of a factor is linguistic insecurity?

P.S. I like the “Han Solo-Chewbacca communication” concept Jared brought up in the podcast!

22

Feb 2019Characterplay with Buttons

Spotted in Shanghai:

The word is 扣子, meaning “button” (the kind you sew onto clothing). In Chinese, the kind of button you press is a totally different word, and even has the verb for “to press” as the first character: 按钮. (When you think about it, it seems kind of dumb that we use “button” for both of those things in English. Sure, you can say “push-button” in English, but it still feels to me like whoever decided to use the word “button” for the new kind that you press wasn’t super bright…)

Here’s the larger context:

20

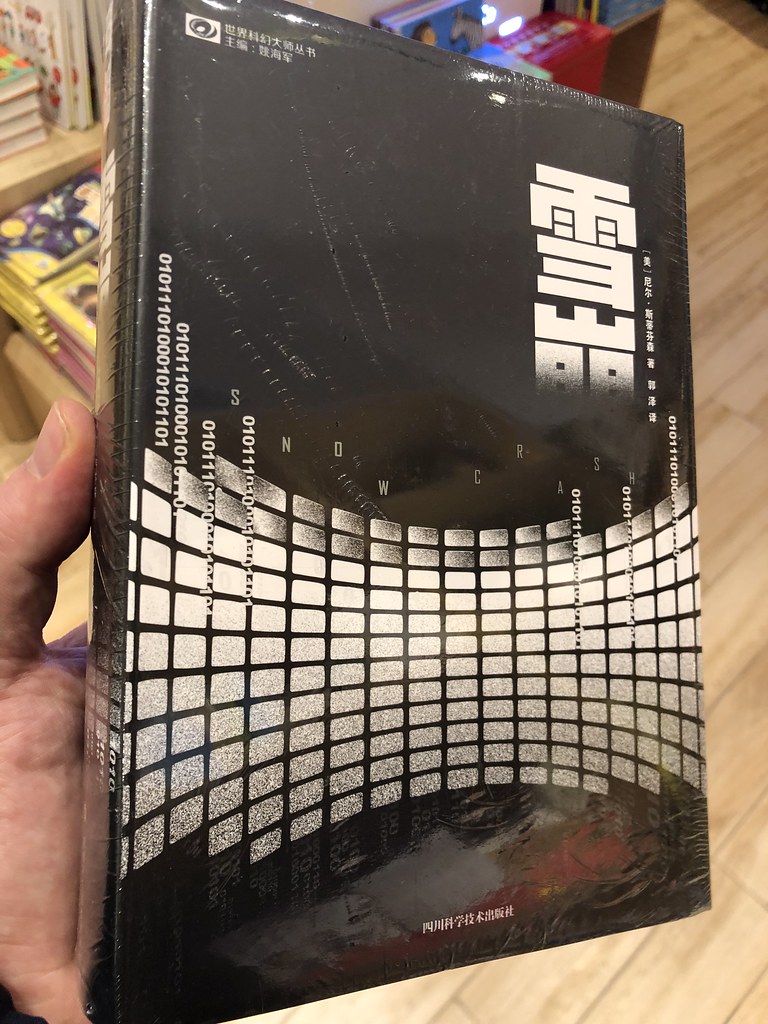

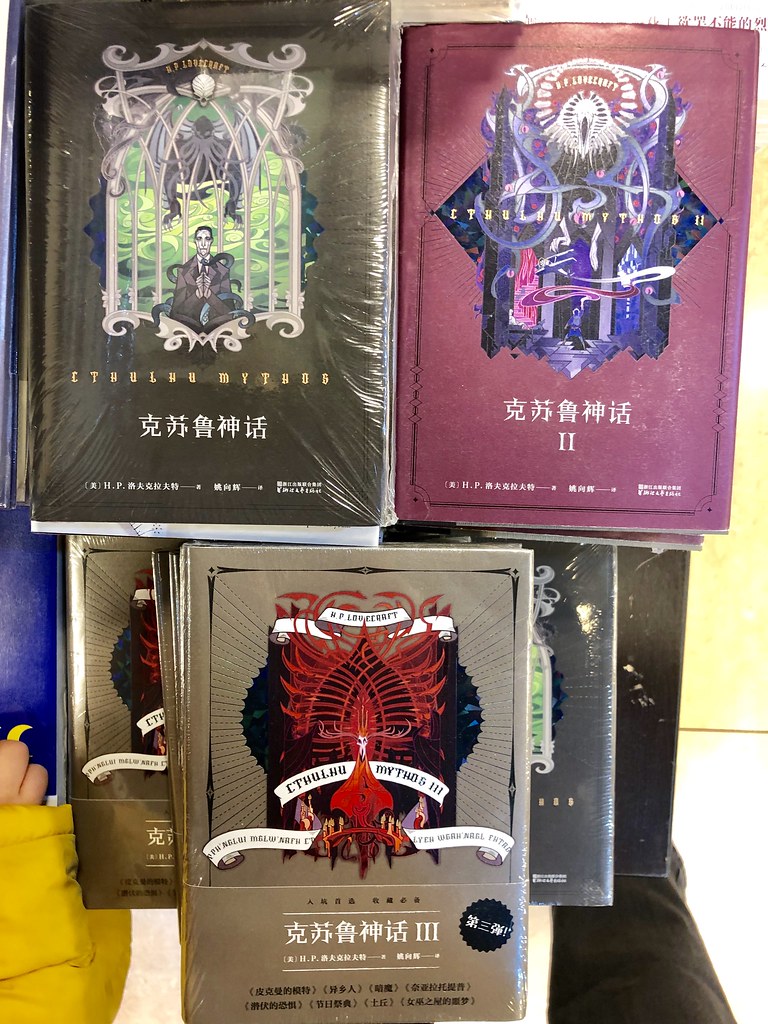

Feb 2019Cthulhu in China

It’s always fun to discover cultural tidbits from home unexpectedly implanted in China, whether it’s Marvel superheroes, Steve Jobs, or even potatoes. So it was fun to make these two book discoveries in my local bookstore:

Snow Crash

Snow Crash (雪崩) is a classic cyberpunk novel by Neal Stephenson (尼尔·斯提芬森). 雪崩 simply means “avalanche,” so it’s a shame that this translation seems hardly nuanced. But still… it’s Snow Crash!

Cthulhu

H. P. Lovecraft‘s Cthulhu Mythos (克苏鲁神话) is well-known by all American geeks, but this is the first time I’ve come across it in China. Three volumes, even! The books were shrink-wrapped, so I couldn’t see exactly what they contained without buying them.

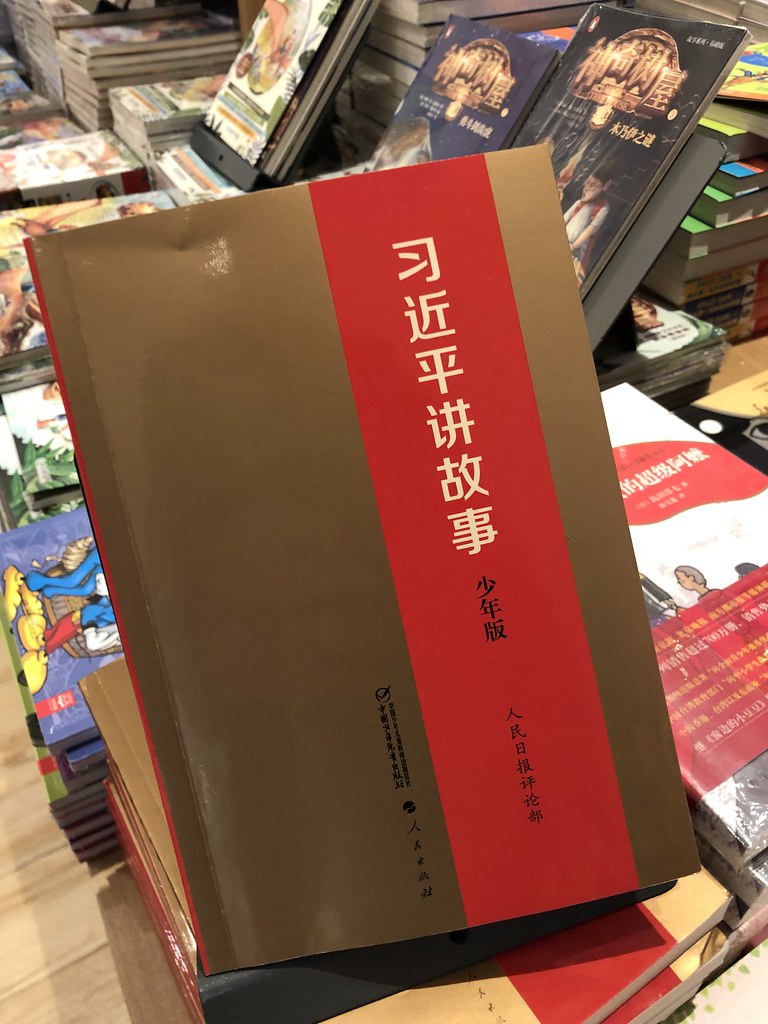

Xi Jinping’s Stories

Finally, there’s this gem: 习近平讲故事 (Xi Jinping Tells Stories). The book was with children’s books, but a quick glance revealed that this was not a book for kids. Yes, it was stories, but it was the sort of pretty straightforward propaganda the cover suggests, intended for adults.

12

Feb 2019You Can Learn Chinese (Podcast)

At the end of 2013 I left ChinesePod and podcasting in general. I haven’t missed it too much. Those podcasts were a ton of work to get right, and I’m happy to tackle the problem of learning Chinese from different angles with different approaches at AllSet Learning.

In 2019, though, it looks like I’m doing a podcast again! This time it’s with my partner at Mandarin Companion, Jared Turner, and it’s called the You Can Learn Chinese podcast.

This podcast is about learning Chinese; it doesn’t teach Chinese. And while it may sound like it’s for beginners, learners of all levels should get something out of it. As the name suggests, it’s also more motivational and conceptual than technical. For example, rather than talking about how to set up Pleco or Anki for optimal flashcard review sessions, we might talk about how flashcards can be a useful tool but are not a one-size-fits-all method, and you can learn Chinese without going full-on flashcard crazy.

Here are some of the things I like about this podcast:

- Produced and managed by Jared and not me (Yay, I’m lazy!)

- Lots of guests, sharing a wide range of experiences learning Chinese (some to very high levels)

- I get to talk about certain academic topics a bit (but no thesis writing!)

- It’s kind of cool to be behind the mic again, but with less work pressure

Anyway, if you’re interested at all, please check out the You Can Learn Chinese podcast and let me know what you think. It’s new and still evolving.

17

Jan 2019Pye, Pi, Pai

A clothing store in Shanghai:

So π + 派 = this. It doesn’t seem clever in any way, but it’s kind of interesting.

11

Jan 2019The Hardest Thing

We China expats complain a lot. It’s pretty often that you hear people talking about “the worst thing” or “the hardest thing” about living in China. You hear complaints about the food, cultural issues, linguistic challenges, internet woes, pollution, etc. Many rivers being cried over here.

And I’ll admit, I’ve thought about this issue myself (enough to come to a conclusion). The biggest frustration for me over the years has been related to the internet, and it’s gone from being a personal nuisance to a business issue.

But the real hardest thing is something that crept up on me. It’s something I never thought about when I initially made my decision to stay in China indefinitely, and it’s only been in recent years that I’ve really confronted it.

The hardest thing about living in China as an expat long-term is having your family grow old while you’re not around. It can be hard to accept how the U.S. has changed in recent years, but seeing one’s parents older and frailer with each visit is the absolute hardest. It really makes you question your life choices, even though in my case, my parents have always supported my life decisions.

Especially after having children of my own (ages 4 and 7 now), I’ve made it a priority to get home at least once a year to spend time with my parents and my sisters. But time marches on, and one visit a year feels woefully inadequate when the unmentionable finally happens.

We really don’t have much time, and the years fly by.

I’ll miss you, Dad.

01

Jan 2019Outlier Teaches You How to Learn Chinese Characters by Video

Way back in 2015 I recommended the Outlier Dictionary of Chinese Characters for Pleco. It’s been a while, but the team has been busy. They’ve been continuously adding to their character dictionary, and they’ve also created a video course for self-learners that want to learn Chinese characters by the Outlier method.

You can see an example video on YouTube which outlines the “Pipeline Strategy” for learning Chinese characters.

I don’t routinely plug other products, but this is one I really believe in. These guys know what they’re doing, and they are utterly dedicated to their cause. You may notice in the video that they’re not exactly “entertainers,” but they don’t beat around the bush and they do know what they’re talking about!

They’re starting a video class next week, and if you’re looking for a way to self-study with video guidance from experts, this could be what you’ve been waiting for.

Here’s the link to sign up to the course. (It’s an affiliate link, so if you choose to sign up you’re supporting Sinosplice too.)

Make it a great 2019!

13

Dec 2018The Intermediate Chinese Grammar Wiki Book is out!

The Intermediate Chinese Grammar Wiki Book is available:

It’s really been a ton of work editing, rewriting, and reworking all kinds of intermediate grammar points for the new book. The result, however, is both a solid book and better wiki content. If you want to support the wiki, please buy the book! (If you don’t need another stack of paper, I highly recommend the ebook. The instant search alone is really great.)

Special thanks to Chen Shishuang for all the work she did on the B1 grammar points, beginning years ago (not just one). (I bet there were times she wondered if the book was ever really coming out!)

AllSet staff Li Jiong and Ma Lihua were amazing proofreaders, and intern Jake Liu was quite a trooper as well. I also need to give a shout-out to wiki user extraordinaire Benedikt Rauh, who caught quite a few errors and emailed them in over the course of 2018.

Our designer Anneke Garcia did an awesome job on the cover. (If you need design services, I can put you in touch.)

For me, one of the best things about finishing a massive book like this is that I don’t have to work on this book anymore. (Maybe I have a tiny inkling of how George R. R. Martin feels?? Ha!) Sure, I love me some intermediate grammar, but there are so many other projects I can’t wait to dig into. 2019 is going to be a great year for AllSet Learning.

Now for some Christmas vacation…