Vocabulary as Puzzle Pieces

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about vocabulary lately, and how many learners treat vocabulary as the sum total of language learning, as if memorizing a bunch of vocabulary was basically all you had to do to learn a language. It got me thinking about how these learners must be conceptualizing vocabulary, about what mental models they must be using. This led to thinking about metaphors, and what metaphors may be in their minds.

Vocabulary as Building Blocks

Referring to vocabulary as the “building blocks” of a language is fairly common. Anything you want to say requires vocabulary, much like anything you build requires building blocks (bricks?). I suppose that feels like it works on a very elementary level.

There’s one big problem with this, though… “building blocks” or “bricks” are typically uniform and largely interchangeable. While it would be convenient to be able to speak with words that were “uniform and largely interchangeable,” that’s not really how this whole language thing works! Every time we speak, we need to choose our words to convey our specific meaning. There’s a bit of interchangeability here, but not a lot!

Vocabulary as Legos

If you think of regular old bricks as being uniform and non-specialized, you might think that LEGO bricks make a better metaphor. So many different kinds of bricks, with different functions, colors, sizes, etc.

Still, those LEGO bricks are all largely interconnectable, and there’s quite a bit of repetition. It’s still not quite as demanding as the units we use to build language-based meaning.

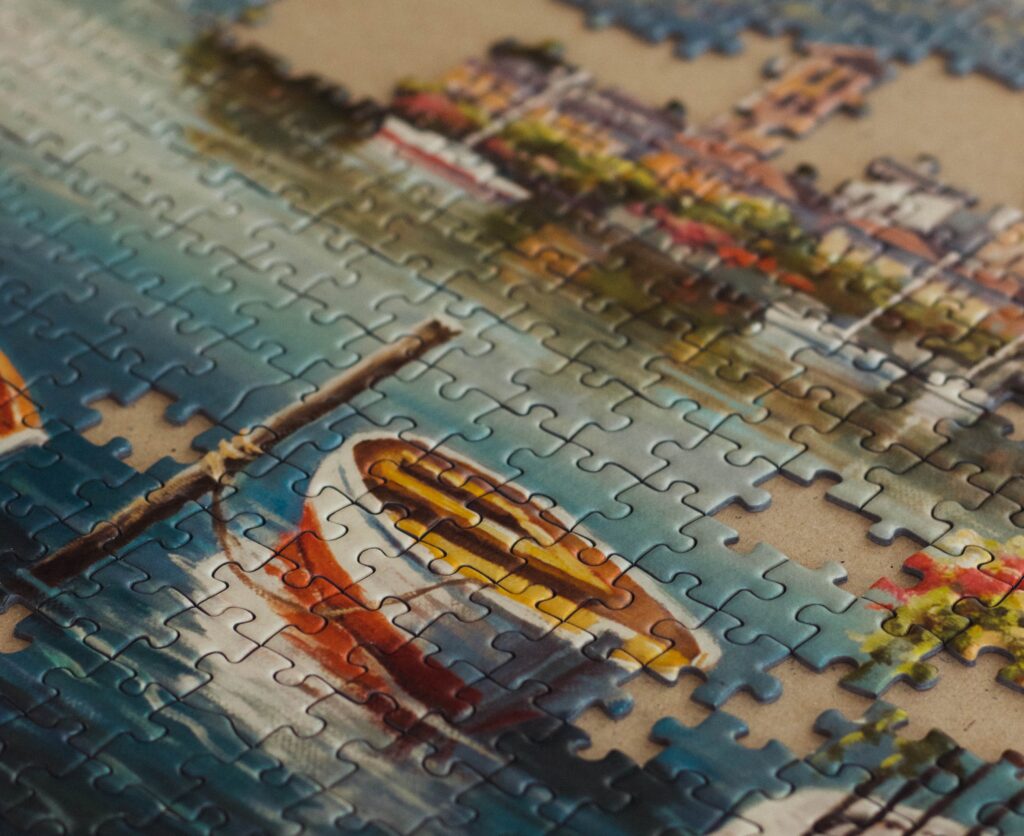

Vocabulary as Jigsaw Puzzle Pieces

I propose that we should be thinking of each vocabulary item as more of a puzzle piece. When you don’t have the right piece, not just any similar piece will do. The others don’t fit. And it does take some time to familiarize yourself with the pieces, identify the ones you need, and start to assemble a picture.

Furthermore, if you’re a word hoarder and are not practicing using those words in any way, you’re basically just working on a big ‘ol bag of puzzle pieces. Sure, you’ve got the pieces, and sure, they can be assembled into a picture, but that takes time and effort.

However, if you’re regularly looking at those new pieces and trying to figure out how they fit with the other pieces you already have, then you’re steadily making progress toward forming that picture. And the picture is the meaning that we’re all striving for, the meaning that words are meant to convey.

Yes, based on what you‘ve explained, your puzzle piece metaphor makes more sense.

I (and please pardon the fancy words; they are the best I have to name this intuition) tend to think in terms of Voronoi diagrams in semantic fields—though by ‘field’ here I mean something a little closer to the mathematical sense of the word than I think linguists usually do, in that these are high dimensional spaces in which terms can operate on each other to increase their reach. I find this encourages useful questions like “is a sword a kind of ‘knife’?” and “is a ‘neighbourhood’ fixed to the map, to the speaker, or to the item under discussion?” But the key point is that words(?) implicitly both define and then partition a space through competition of central notions.

As to what a ‘word’ is, though, I give up. If French had originated in North America, the rigidly ordered packet of pronouns and things that occur before the verb would probably be considered part of the same ‘word’ as the verb. If it had originated in China, the inflectional material that at the end of the verb would likely be considered separate ‘words’. I begin to suspect that Western ‘words’ are mere orthography, and Mandarin ones often something in the space between metrical phonology and coding theory.

If these are puzzle pieces, boy, that’s a pretty abstract and highly encoded puzzle ;).

Ha ha… that kind of model or thought experiment is all good fun, although not so useful to the typical language learner!

I may be missing something, but I see a problem with the jigsaw puzzle metaphor. Essentially because each piece can only fit in one place, whereas with language, there are always alternatives. The choice of words may not necessarily be the most elegant, the fastest, adapted to the context, what native speakers would use, but once you’ve mastered the core elements, there is no single path. And so, architectural metaphors such as Lego to me would seem to embody that flexibility.

The jigsaw puzzle metaphor might apply to the fundamental (grammar) constructs though. Just a thought

No, you’re right… It’s not a perfect metaphor. It’s just better than the “building block” metaphor I run into fairly often.